Actual Objects

Graphics by Collin Fletcher

Where does the name Actual Objects come from?

The name comes out of our research into the materiality of technology. It’s the idea that digital things contain embedded material, and emotional knowledge; the cloud is not bodiless. So we see the work that’s created in the studio—primarily digital imagery and films—as “actual objects,” artifacts made of simultaneously 0s and 1s, but also rare metals, spinning in an HDD, intrinsically tied to the hyperobject of computer production. In the time of climate collapse, and our increasing digital existence, we think it’s extremely important when working with digital tools to evaluate the extent of materiality that compose our work.

How did the members of AO come together? And why did you decide to work together rather than individually?

We all met about seven years ago, and have been working together on various projects since. Claire and Rick lead the creative production, and Nick handles everything else.

When developing a new concept, or project, how do you map out your process? Are there any guidelines that you set for yourself?

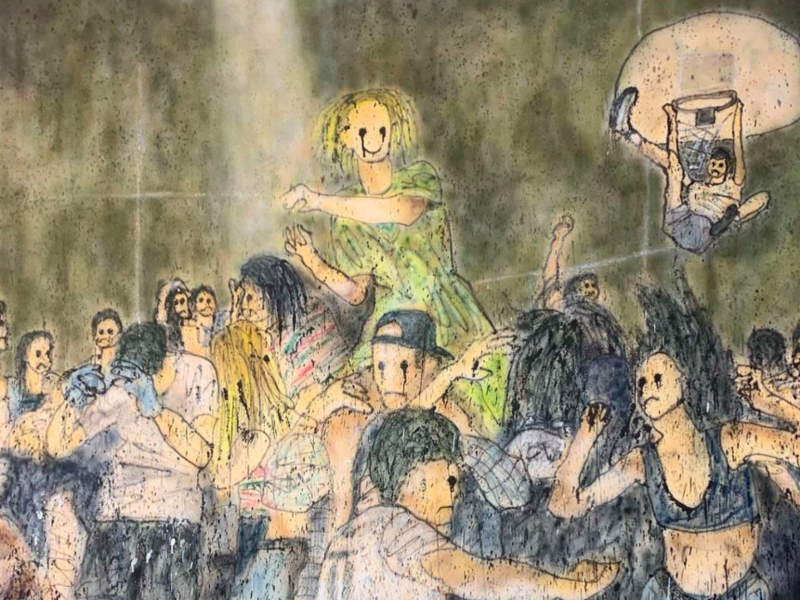

Most projects begin as a conversation between Rick and Claire. Our formal collaboration is relatively new, but we’ve made work, whether it was Claire’s drawing & painting, or Rick’s music & architecture, alongside each other for 7 years. So, we’ve honed a tight conceptual and formal language that informs all of our work. Every project presents us with something we don’t know how to do, so we usually start there. How can we make this particular thing happen? We troubleshoot, and research until we inevitably figure something out—and that solution is usually the first moment energy is really breathed into a project. From there, it’s pulling references, developing narratives, talking to our brilliant friends / AO team, drawing, photobashing. We’re a little all over the place, honestly. We tend to work fast, and for long hours, very much guided by our intuition, and not very much planning.

Is there anything that scares you?

Claire has an injection phobia; and Rick has a fear of heights, and mice in the bedroom. Nick has a fear of reborn baby dolls. Other than that, climate disaster.

Since much of your work is video based, are influenced by cinema? If so, what films inspire you?

We kind of fell into making films—it ended up being a natural transition from painting, and music/architecture. Of all the art forms, film is funnily enough one of the ones that we’ve paid the least attention to, but have found to be the most representative of what we’re trying to say—film is the strongest combination of image, sound, and space.

What is your relationship to nature?

Nature is a problematic term in 2020, and the way we would define it is perhaps unconventional. Nature as an untouched, vast wilderness struggles to exist in the age of climate crisis; it no longer sits patiently awaiting manifest destiny. We believe nature is something all-encompassing—a motherboard is just as much “natural” as a pinecone, or thistle plant, or star, or jaguar. Classic dystopian futures are spaces devoid of that quintessential, sublimic wilderness, replaced by computers, and plastics; white walls with some well-manicured gardens. We think that breaking down the implied separation inherent in nature’s definition—the wall between animal and human, between technology and ecosystem—breaking down this line might give us clarity to coexist as our civilization continues to accelerate.

When was the last time you dreamt?

We probably dream every night, but doubt dreams are very informative to our practice.

How does architecture inform 3D design?

As an architecture student, Rick was never interested in making buildings—most of his time was spent making experimental electronic music. Outside of the technical knowledge that architecture brought, it gave us an understanding of composition, and of pace, a foundation by which to create, and assemble disparate disciplines together.

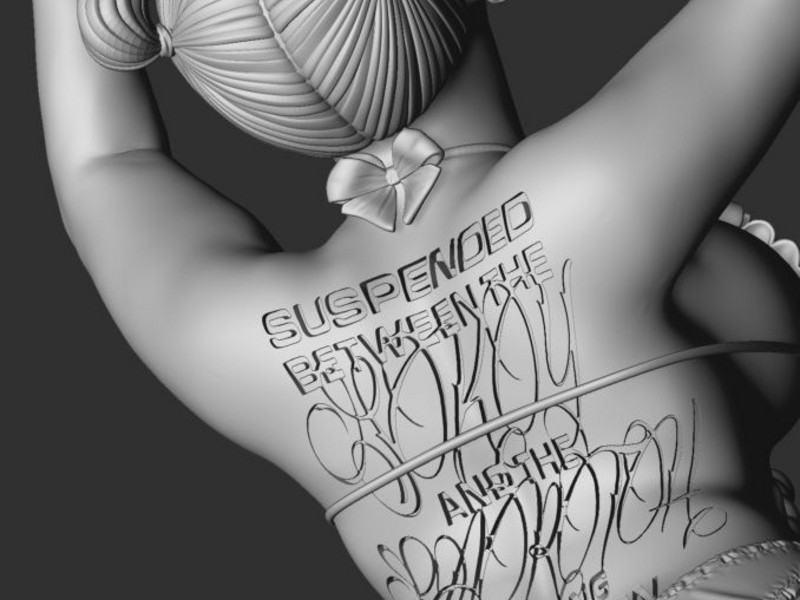

The Marine Serre F/W '19 Radiation film is very much a digital runway—did you work with live models? Are reference images a common practise?

We didn’t work directly with live models for that piece, but have in the past, through motion capture, and 3D scanning. For this project, everything was created by hand: the models are sculpted and textured first, followed by 100s of reference photos of garments which are then hand-patterned in a 3D clothing program. These are then collaged, and assembled into the final garments you see in the film.

What are some unique challenges of working in 3D; and how do you overcome them?

The world of 3D is vast, and ever-expanding. We’ve barely grazed the surface of what’s possible to do and learn, which is simultaneously overwhelming, and invigorating. We hope to always be on the frontlines, working with emerging technologies, which is expensive, and labor intensive to constantly build new skill sets, understand new interfaces, research, and troubleshoot. It’s tempting to just relax into what we’re already familiar with & good at, but the desire to push ourselves is stronger.

Can CGI change the way we perceive reality?

The larger question here is whether (or if) CGI can be considered something real, something with a material, or emotional knowledge. CGI certainly has a shape to it, a list of aesthetic and technical attributes, and maybe even some exciting or novel traits, but is it tangible? The highest achievement for game developers is creating something immersive, and I think what’s more important to us as a studio is to create things that feel like they aren’t trying to mimic reality, but rather an uncanny subversion, to create an alternate perspective through which to view our non-CGI existence—the production of reflections, and mirrors.

Who do you find original?

We don’t value originality very much—the act of making is entering into a long conversation that’s been going on since the birth of humanity. We think the concept of originality undermines the work of all of our influences, references, predecessors, colleagues, etc. In the age of the poor image, we consider the concept of originality, and the “hero artist” to be irresponsible. That said, we’re inspired by Marlene Dumas, Arca, Marguerite Humeau, Amnesia Scanner, Graham Harman, Chino Amobi, Ian Cheng, Michael Armitage, Hito Steyerl, Ed Atkins, Isamaya Ffrench, Gerhard Richter, Marine Serre, Timothy Morton, to name a few.

Chess, or checkers?

Tennis.