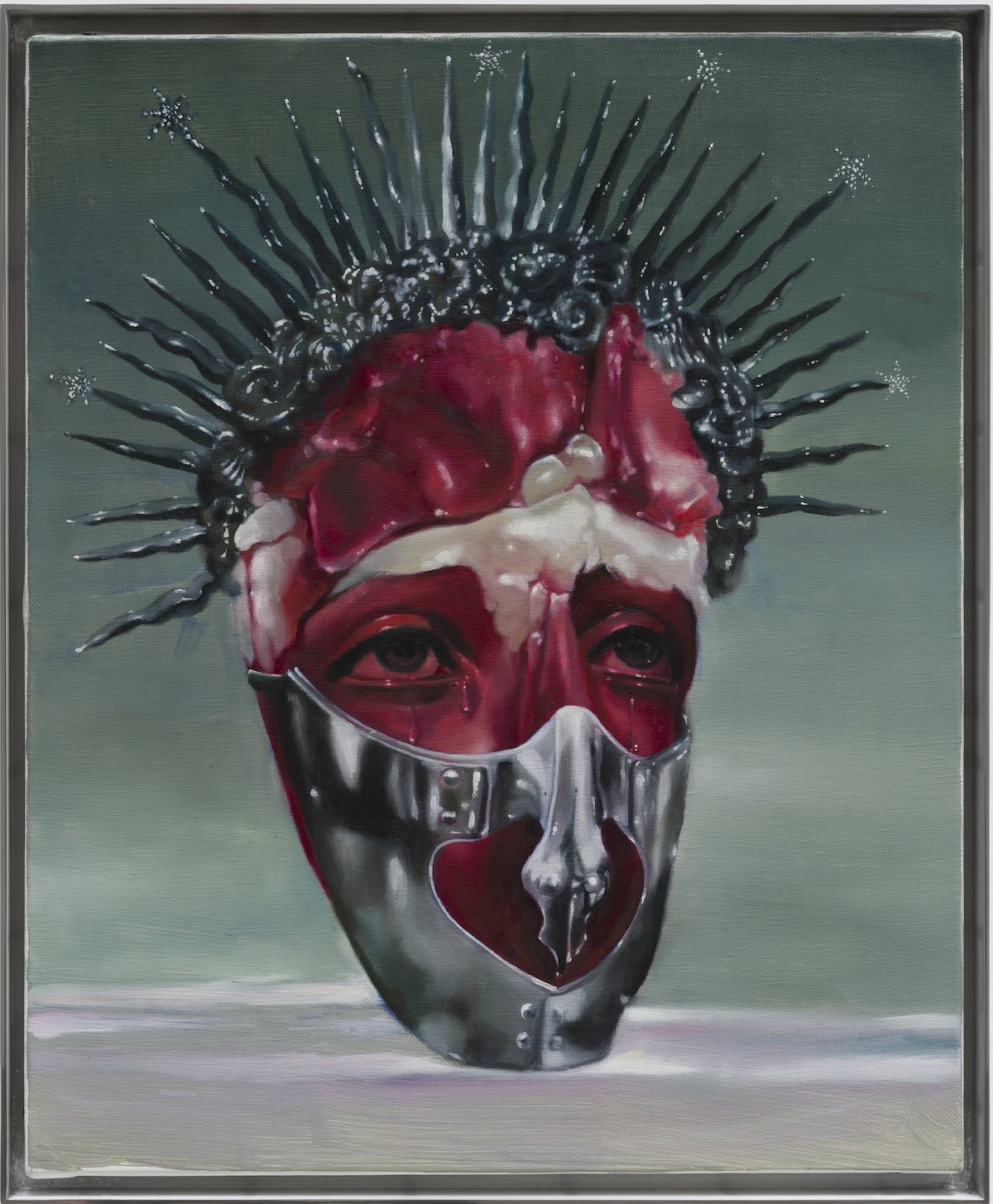

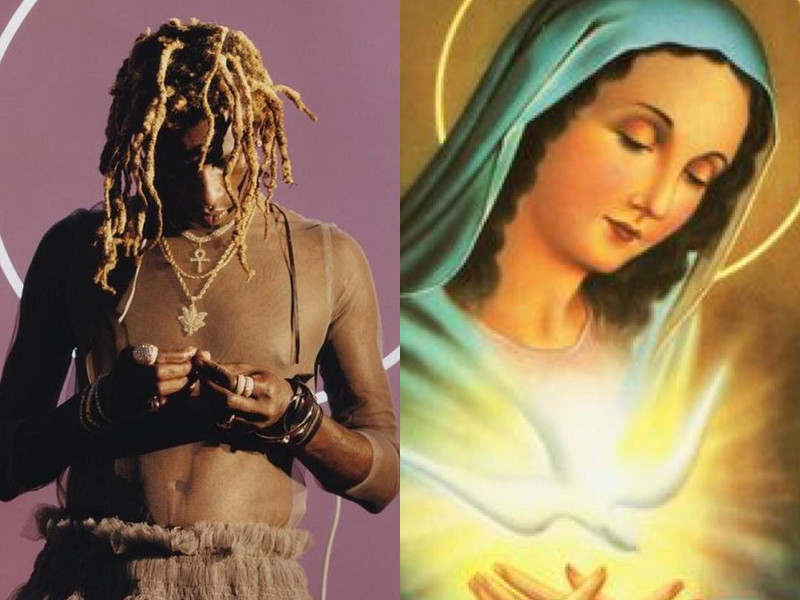

Anthony Jamari Thomas' Divine Intervention

For artist Anthony Jamari Thomas, however, the story doesn’t end there.

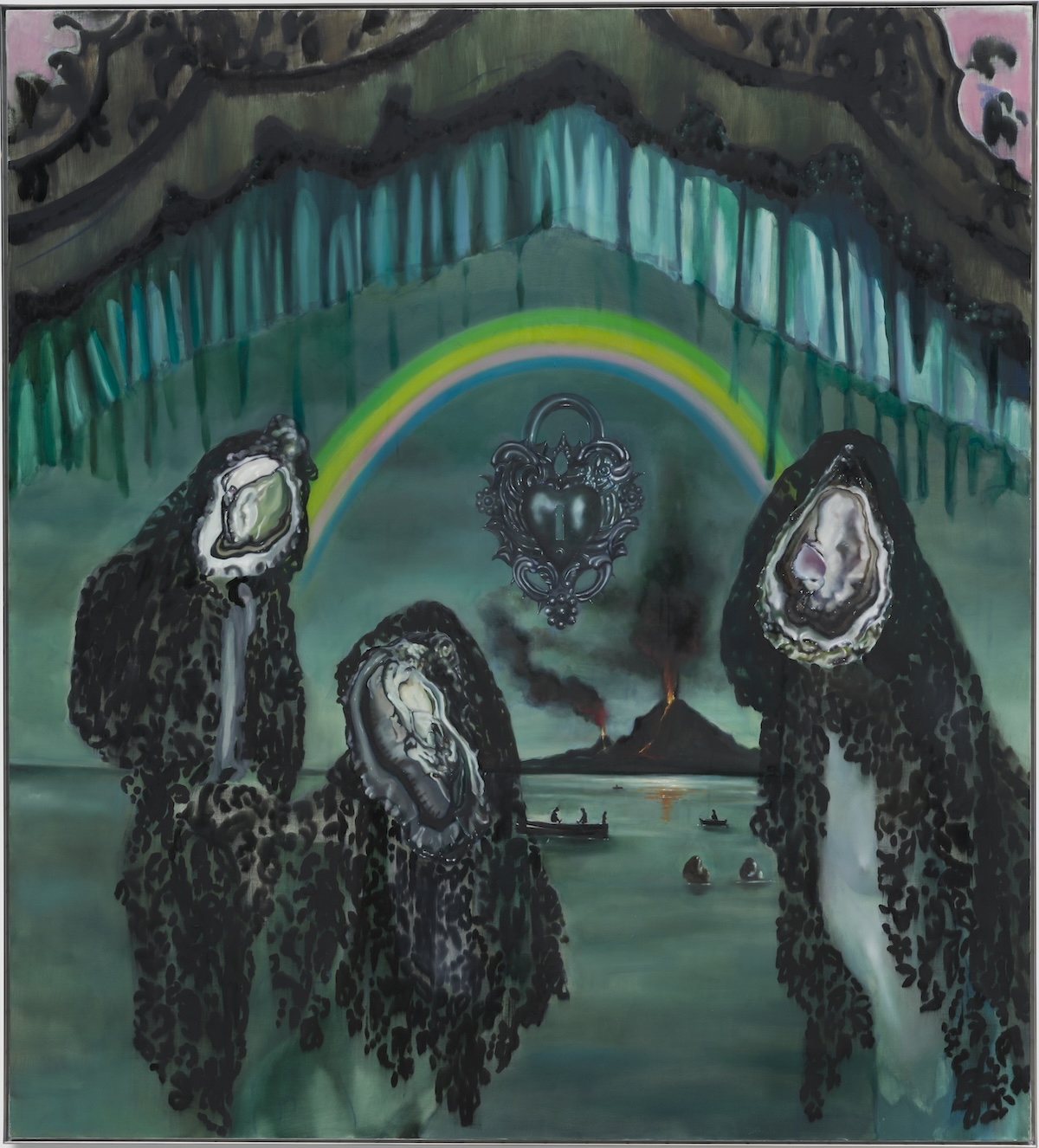

We live in a particularly repressive political moment, where those in positions of power have demonstrated time and time again that they do not deserve to have that power in the first place. One of the greatest examples of this has been the ongoing treatment of immigrants in this country. It is this very treatment that forms the conceptual crux of Thomas’s new book, LAMB. Published by Paradigm, this publication is not only a bold exploration of the ways in which the migrant body is handled—both literally and symbolically—but an acknowledgement of the sacrifice and bravery inherent to migrancy itself.

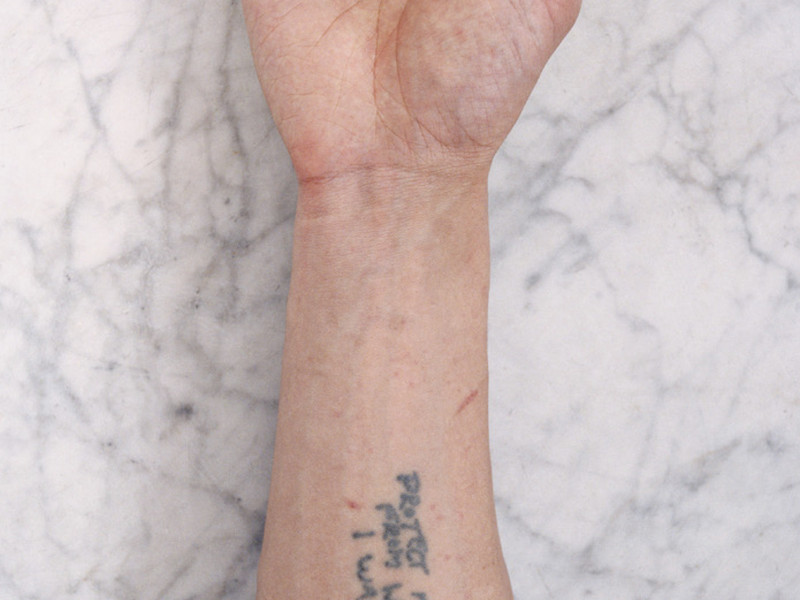

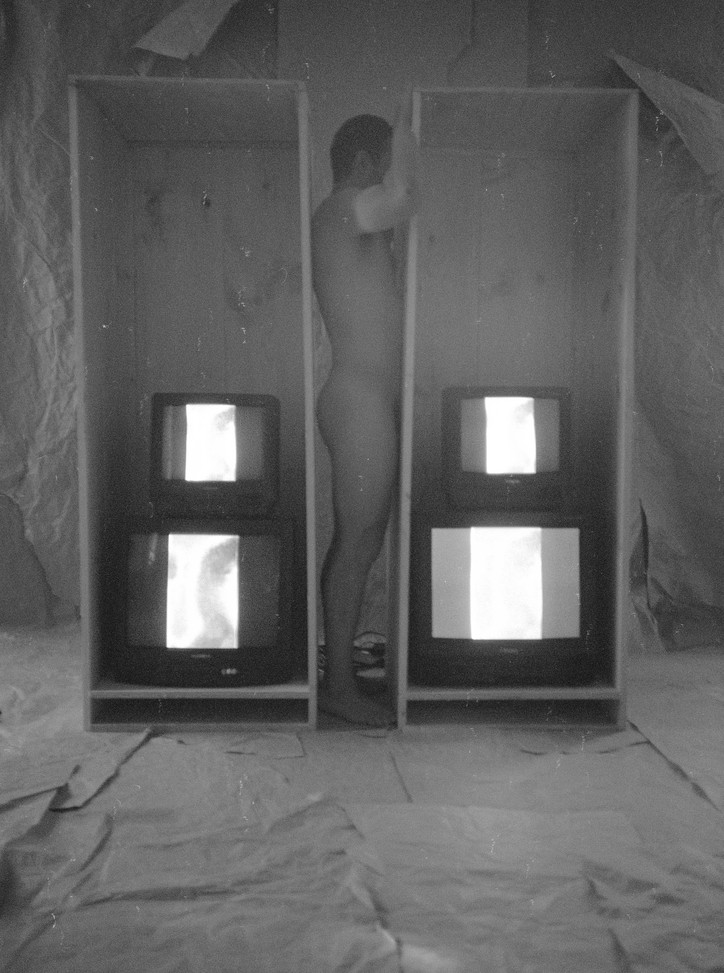

In addition to the book, Thomas supplemented LAMB with a performance piece, in which he spent 24 hours inside a wooden box without food or water in protest of and in homage to the migrant experience, alongside alternative R&B artist BarringtonELECT, who curated the sounds and sang to enhance the atmosphere. One can always pledge allegiance to a worthy cause, but there will always be that conveniently comfortable distance that separates the one who has experienced the act and the one who protests for the one who has experienced it.

Thomas, in his own capacity, has worked to mend that distance, to step into the shoes of and to illuminate the experiences of the brown body, in the best way he knows how.

What initially sparked your interest in art?

When I was 17, I dealt with depression and anxiety on a great level. I wanted to take my own life—when I was 13, as well. Then, when I turned 21, I battled alcoholism and it took me a little bit to get sober. So, I wanted to find a way to be therapeutic about how I was dealing with my depression. I started to have suicidal ideations, and that’s when I thought, ‘Man, this has to get fixed.’ I come from a Baptist Christian background, so therapy and all that other stuff doesn’t really work—it’s a ‘We ain’t paying for that’ kind of situation. As a kid, I remember my mom told me once—and she’s the most incredible person in the world—but she was like, ‘Just go get some food, go to bed and when you wake up, you should be okay.’ Of course, I knew that just wasn’t going to be the end of it.

So, one day, while I was working on this project to honor my grandmother, I had like thirty cents on me, and someone told me to go buy a canvas and make a piece. When I did it, it felt so relieving. I never studied art, I never took studio art. I did art history for semester, and it was basically just memory, so I really wasn’t learning anything.

Did you ever study art?

I did art history for a semester, but no I never did studio art. You just either got it or you don’t. And I feel like god gave me this gift because I didn’t have to seek any academic instruction. So, I’m just thankful that I can create as fluidly as I do, and to be able to make a reality for myself through it, because it saved me from the reality that I was in.

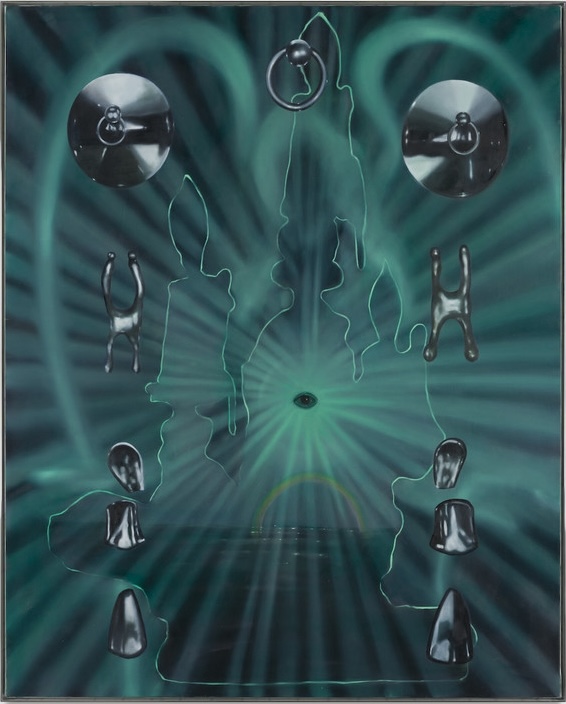

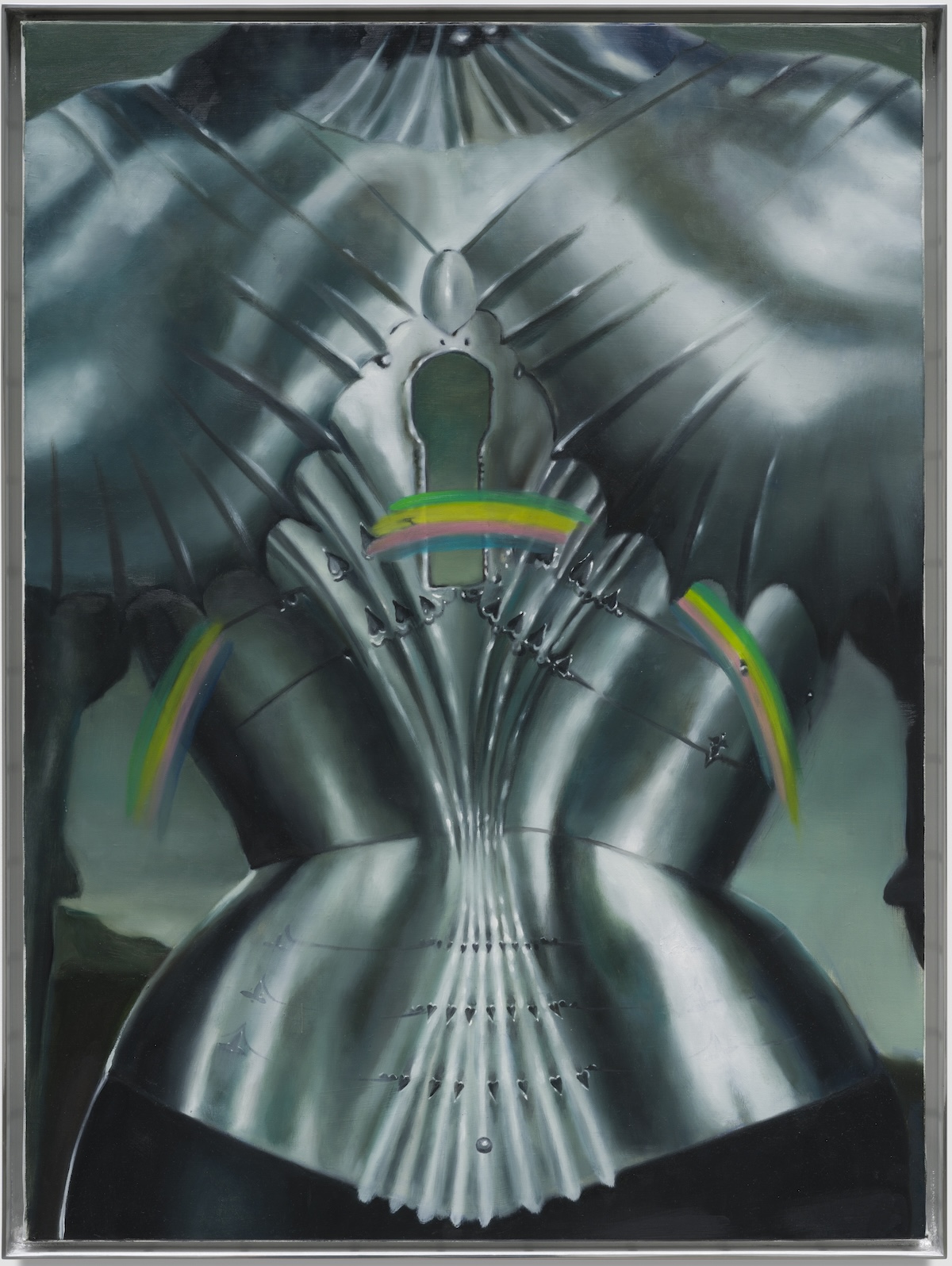

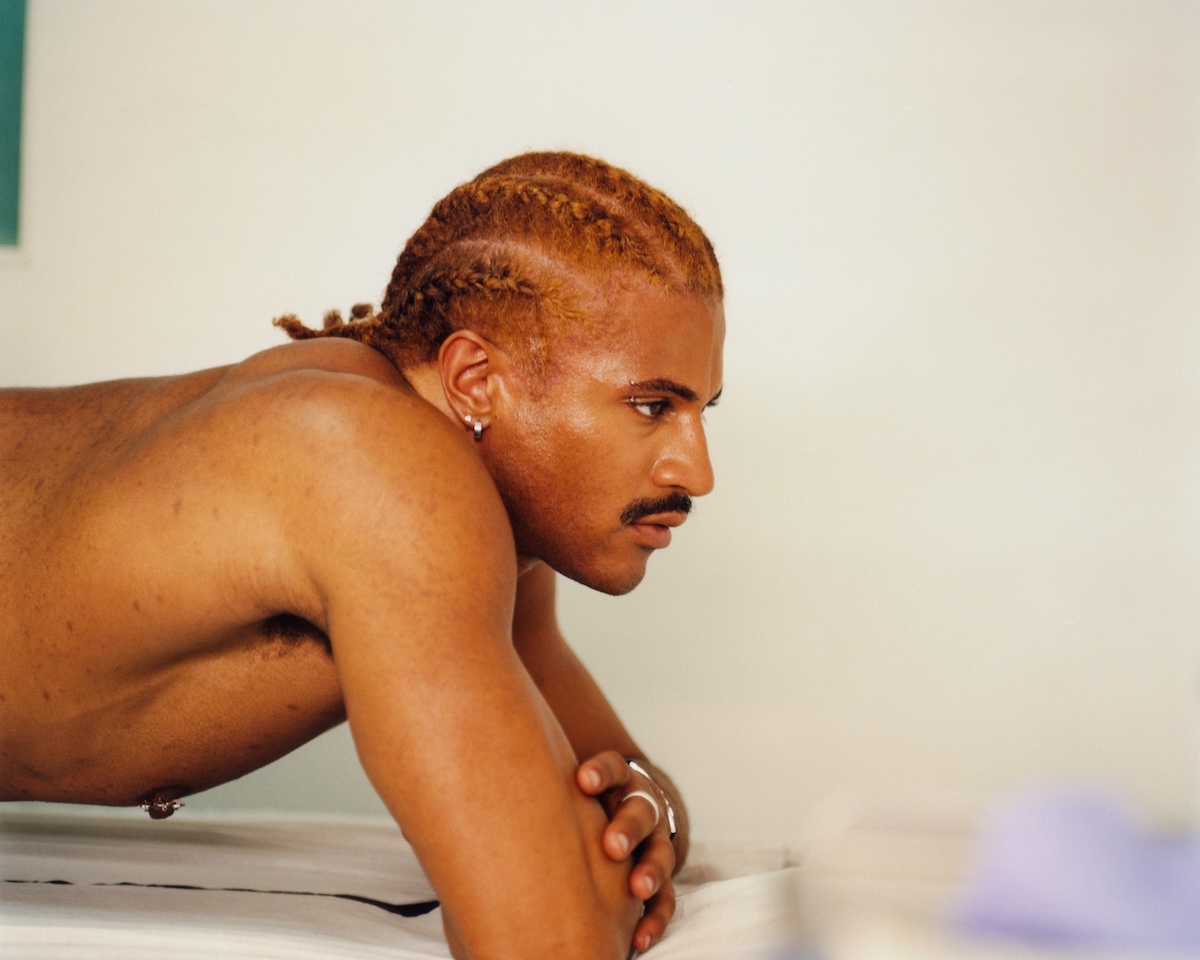

What to you is the correlation between body and power? Why is the body the most powerful instrument, or the most powerful, visceral medium of expression?

I think it’s like an inner-chamber thing—the body has a way of relying on space, and space relies on the body. The crux of my work deals with the black body, and examining how the black body exists in space in relationship to institutions, to history. Our bodies have been placed in a very controversial time because there is this tension where we want to live in a contemporary way and try to understand what our blackness represents now. But we want to understand what it was before us, and what it represented before us, and the mythology behind the black body because you kind of don’t know your beginnings until you find, and discover, and unearth—and it takes some work to do that.

I’ve understood the body as an object that transfers the spiritual and the divine—it transfers a lot of the things we can’t see on the day-to-day. The body is a prime medium for all things—for policy, for socio-economic ideals. It’s a vessel that can channel so much, but once you start adding a geography to it—where the body is placed, how big or small the body is in relation to its surrounding community—that’s when you start to understand your own body and it’s position of power within the place in which you are situated. So, I think the body and power go hand in hand, but they’re not always bipartisan. Sometimes your body moves on it’s own, and power happens to your body; then your body can posses that power, and power can take over your body—it’s fluid, there’s a synchronicity. Other times, the body and power are totally detached—that’s the beauty of it. But power on its own is a crazy construct I’m still trying to figure out.

Yeah, power is completely relative so it’s almost impossible to define it in a finite way. What place—fictional or non-fictional, symbolic or literal—is the single biggest source of inspiration to you?

My aunt’s home. My Aunt Mary passed away April 21 at 2AM—I was the last person she saw before she died. She died twice in this lifetime actually—once, in ‘97 for ten minutes, and my mom brought her back to life with CPR. Then she unfortunately passed away in April. She was everything to our family. She was an archivist, the religious crux of the family—we all knew Christianity because of her, and she inherited Christianity because she grew up in the segregated South. The first political means of activism in the South against racism was religion—it was the church, a congregation of people that looked like you, speaking to a higher power that can hopefully save you from your reality. Then, she came to Bed-Stuy in ‘62. She had four sisters and they all passed through her house, because she was the first to move here from Virginia. So, the guest room of that house is where my mom grew up, and where she raised me. Her home has everything in it. We’re talking 1962 to 2018, so there’s family photo albums, memories, all types of doctorates and religious texts, and by the grace of God, when I was eleven years old, she left her home to me.

Now, it’s my space, and the crazy thing is, the back room where my mom raised me is now where I paint—it’s my studio. So, all of the things that I want to explore, all the things that I want to speak on, all the things that I’m curious about—they live in that home.

Like what?

The way my body performs in society, the way money performs in my community, the way space and owning property performs in my community—I contemplate these type of things in that space. There is some type of geographic social-engineering to how my people and I think, because if you place certain people of the same ethnicity within the same community and keep them there for a while through economic means—I’m talking about inner-city, underprivileged, underdeveloped youth—you can control how far these kids are allowed to dream. For me, that apartment is a space where I get to dream as big as possible, because my aunt took those risks.

So, the biggest thing for me—the biggest inspiration for my work—is just love, so much love. But I also want to expose the fallacies of man, and put those kind of points onto the scale. We are very beautiful and gifted beings, but we have tension, we have faults, we are of the flesh, and as you said, with flesh comes power. Sometimes you find yourself losing your power to other flesh, and the actions of other bodies. But that’s why art is so dope—because you get to create your own atmosphere—an atmospheric value that no one can take away, because it’s yours. So, I don’t want to say it’s fictional, but my inspiration comes from just having a space that my family owned that I can create in.

Now I understand why this idea of collective memory resonates so strongly with you and your work.

Yeah, because it was always odd to me to go to my aunt’s and see black cabbage patch kids and those little dolls, and the little black babies praying and playing the drums. Then I would go to my grandmother’s house in the projects and she had the same exact decorations. When you’re in a specific community, there are certain things that we are just drawn to—things that we love to keep around that remind us of freedom, and spirit, and funk, and soul.

What about home as a concept—what is the significance of having a home? What to you makes something a home? And how is the concept of the home visualized and symbolized within your work?

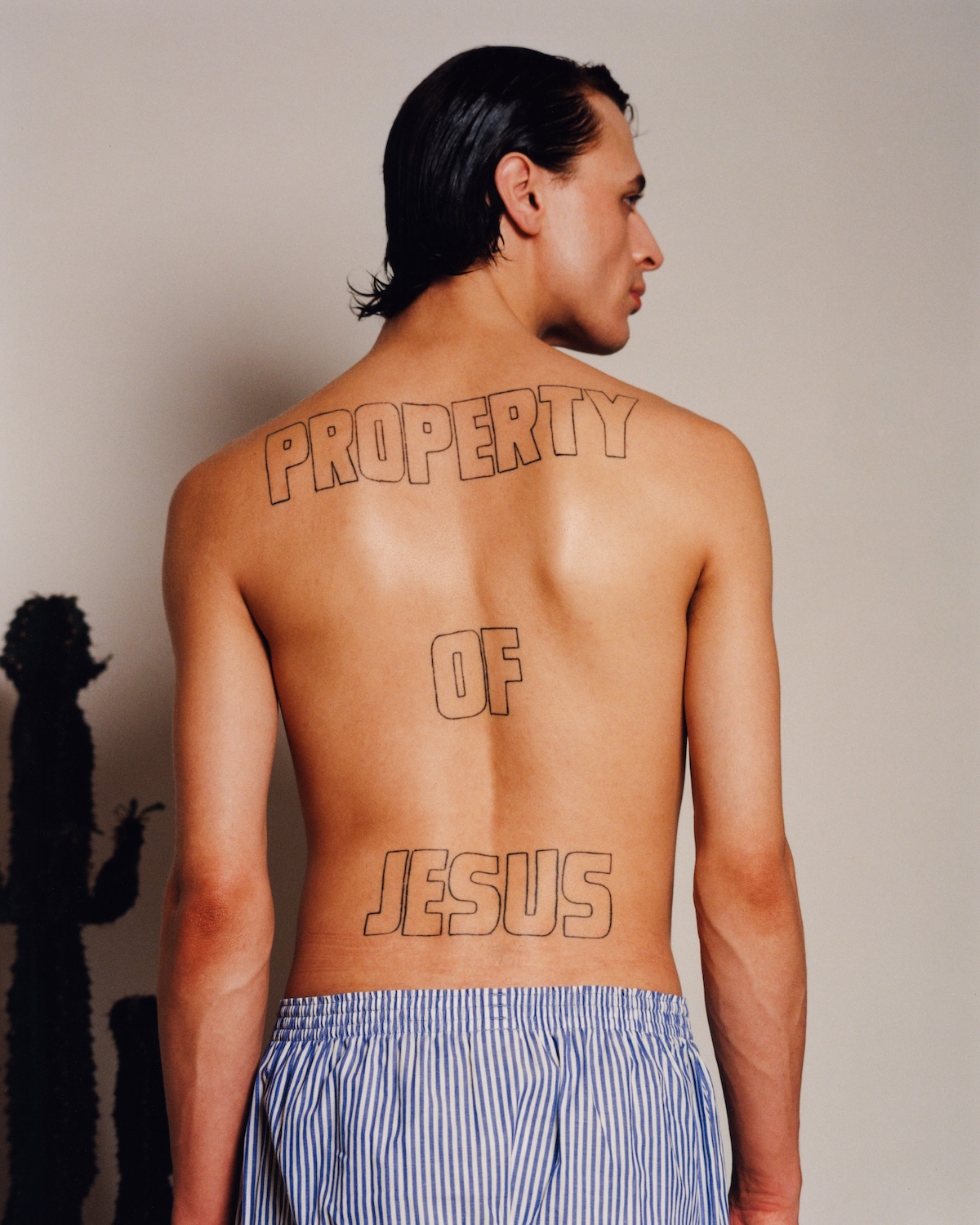

With LAMB, the idea of the home was one of the biggest things. I really like the idea of photography in the sense that you can create an object, and once it’s printed, or becomes digital, it becomes a landscape, it becomes a canvas, it becomes this modular thing. Whatever you place in the proximity of the object, it’s either amplified or diminished. When you give photographs an arrangement, like you see on the wall, you get to see all these different algorithms in between—like jazz, the notes in between. So with LAMB, I was learning two things: the first being to make a photograph symbolic of something bigger than just a selfish vanity; the second was how to make a home for these people that I care so much about and respect, who are constantly moving in order for them to actually have a place—a living sustainability.

After I finished this project, I started to understand that there is a real sincerity behind the migrant body—it’s not so politicized and abused and as flagrant as media paints it as. They’re not victims in the sense that they’re trying to find who they are, because in order for them to migrate in search of a better life, you have to know what you want out of life in the first place. You have to have an identity of hope to try to pursue a dream, then to have that dream taken away from you—taking children away from their families and placing them in these detention centers—the government is crushing dreams on a crazy level. I took the this idea and wove it into my own personal narrative, placing it within the context of my own brown body. Effectively, through history, I am told that I can’t dream as much as I want to—I have to wait until somebody authorizes it, until somebody gives me the authority to say ‘Dream, lil homie, do your thing.’

What I like about the idea of migrancy is that you are constantly moving, constantly adapting your dream to something new, and that’s perseverance, that’s sacrifice—that’s survival. The home is important because you get to expand yourself, you get to stretch your skin out, and fill these spaces with your ideas. I’ve been blessed enough by god to have been raised in a home, and now, to get to work in that space as my studio. So, to think about bodies who want that—who thirst for that—bodies who not only want the typical American dream, they want the chance to have a dream in the first place, and they’re being told no? I can’t even fathom that.

Do you believe artists have an inherent political and/or cultural obligation to use their medium as an instrument of change?

I don’t think it’s an obligation—it’s a choice. As an artist, I know that when you’re down to the wire and just want to make some work, get your therapy down, you’re not necessarily thinking about the world. At the same time, though, circumstances present themselves that compel you to make work that helps you to express yourself and comment on the world. My biggest thing is understanding the beautiful point where public and private meet—where your privatized life becomes something that is affected by public commentary. That’s a choice you have to make—to yourself, ‘Yo, I’m gonna make work that consistently speaks on things that I think are wrong, or things that I think are right.’

Some artists don’t care to do that because they already know how deep and dark this thing goes, and they don’t even want to try to go there, because once you do, if you’re really about that money, you realize, ‘Man, my collectors don’t want to buy my work, because they think that they’re doing some kind of rebellion or protest against the status quo.’ There’s a tension arises around purchasing a subversive piece, and who wants that static? Some people want the smoke—they really want to make a statement. For me, it’s not really making a statement so much as the government and the political regimes my family has lived through, and the times now that have presented me with context and reference to support the things that I feel. I am contributing to the conversation by creating this whole book, but my motive was to illuminate the immigrant body, not to take the light away.

What do you think is the relationship between intention and reception?

Reception is a beautiful thing because you get to take it in, regardless of what the intent was. To go back to the body and power thing—once an action leaves the body and transfers to another one, you no longer care what the intent is, you just want to know, ‘Why did you do that? Why did that happen?’ That reflection is where a lot of reception gets fucked up. So, I try to stay more on the receiving side.

A lot taken away from me this year, and I fought hard to be where I am right now. I love all my brothers and sisters—my family—and that’s why I think this book was so dope—because everybody gave to me without needing a reason to do so—everybody just came out. That’s when you receive and don’t question the intention behind what is being given. Nothing is chaotic, everything is divine intervention, everything is by god’s design. I think if you spend more time trying to understand that you are a vessel worthy of receiving, even the bad things will help you live more righteously.

I think artistic creation is a process of self-discovery. Often you have this idea in your head, but when you embark on the journey of manifesting that idea, it’s nothing like you thought it was going to be, but in the most beautiful way possible. Have you learned anything about yourself through the process of creating LAMB?

Honestly, I learned that I am a prophet through my work. I think god gave me a message and this was my way of delivering it to the world. I put a lot on the line for this, even having made this piece when I was in the depths of depression, and I think it’s a beautiful thing for me, too, because now I know the power of my voice—I don’t take this shit for granted.

Let’s talk about your performance piece. Did you do anything specific as far as mental and physical preparation before the show?

For this, because we’re going to be here for 24 hours, I had to fast. I fasted last week for four days, not eating throughout the day, and going to sleep around 7PM. My body felt so vulnerable and so weak, yet so strong—it was like my body was trying to chose which identity to have. Through the process, I was better able to understand the temptations of the body, and my body chose lust in the sense that the things I don’t normally see as vices, such as food and rest, I never wanted more in my life. The reason I chose to be in this installation for as long as this, is because I felt throughout making the book, things were hella chaotic for me. I lost three family members over the summer and I was in a car accident. I also lost a very good relationship that I had because of a misunderstanding. Through all that, I was still able to make this book, and that, for me, is perseverance. I focused so hard on making this object real in my head that even though all this chaos was happening around me, I was still able to create LAMB.

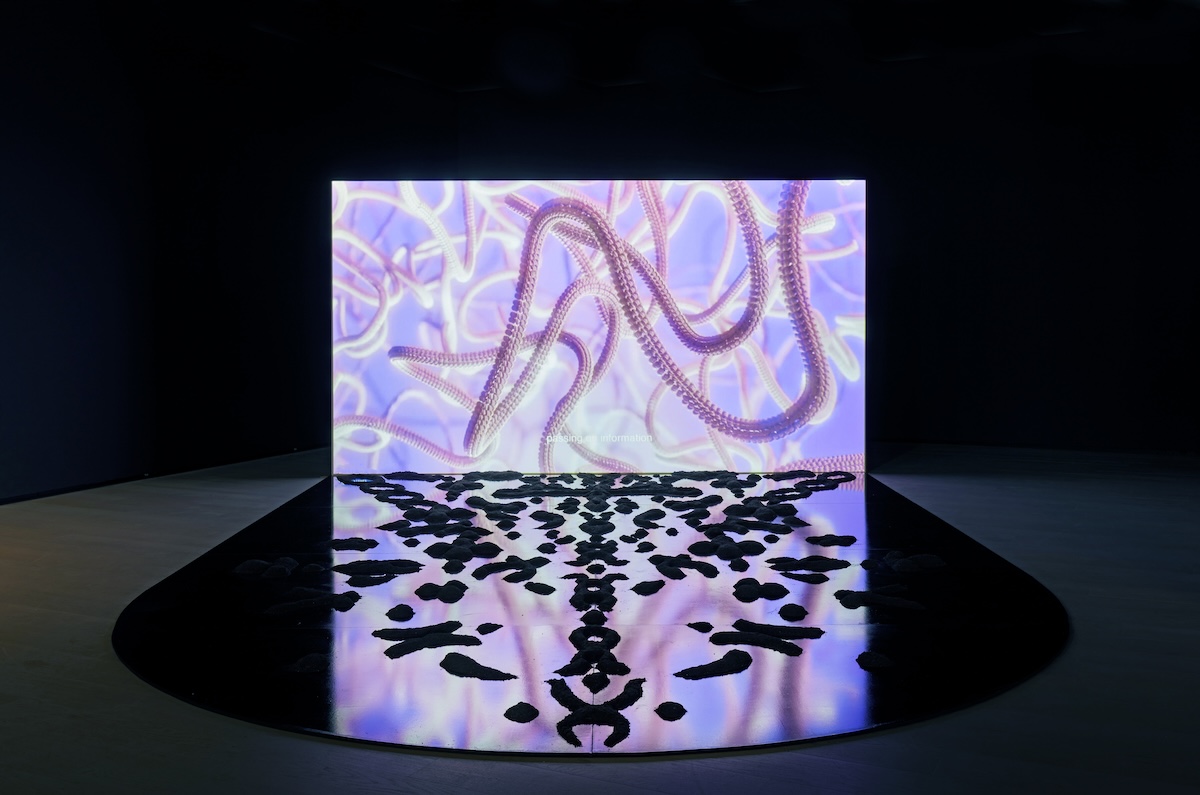

What was the goal behind the installation?

I know there are children right now sitting in detention centers wondering where their moms and their pops are, and I think controlling visibility right now, as a brown body, and also as an immigrant, is incredibly important. On a personal level, my practice is pushing me to think about how to be still, understand chaos in a more strategic and divine way, while also representing these bodies that are being detained and completely mishandled. This is my protest, my sit-in for them. I know I’m just a 27-year-old young homie from Bed-Stuy, and I am so far removed from a 6-year-old Mexican girl trying to eat her scheduled breakfast in the morning. But tonight, we get to connect those worlds, and that’s what I will be thinking about—how to really connect with that energy out there through god.

After we finish this, we’re going to take that energy everywhere—we want it to be as revolutionary as possible. But the revolution isn’t stated by the subject that is orchestrating the action—the revolution is defined by the people. So, we’re waiting on the people to see what we’re doing. We’ll see what happens.

'LAMB' is out now via Paradigm Publishing.

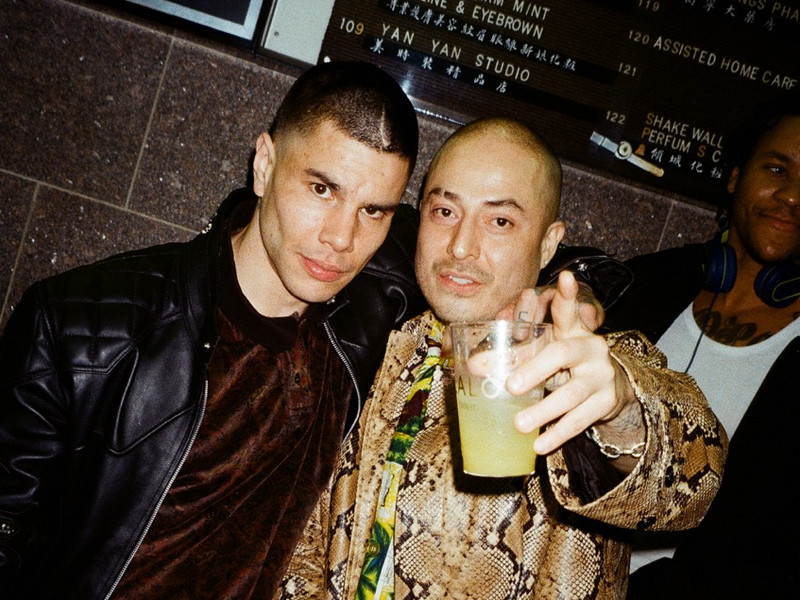

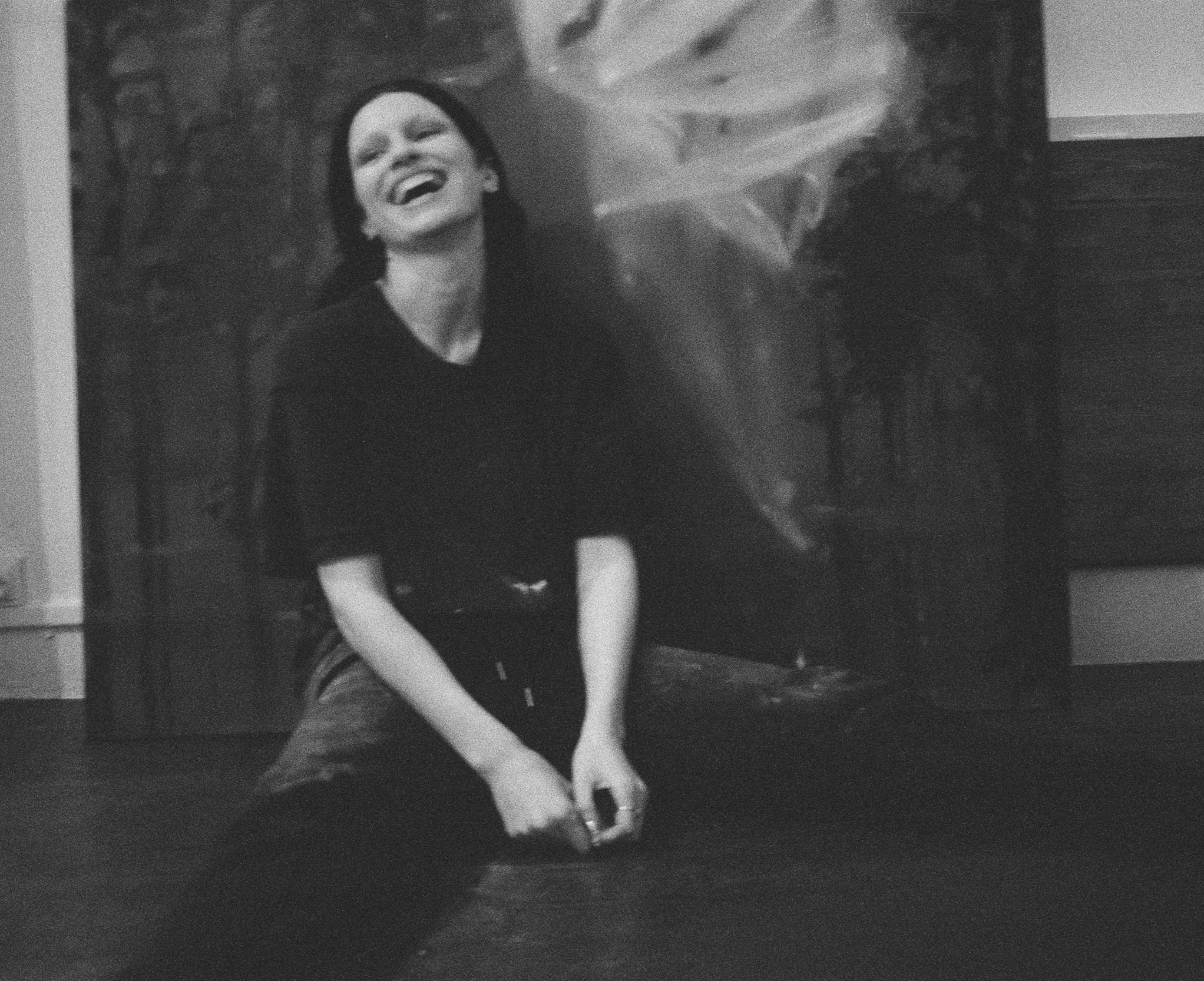

Photos courtesy of the artist.