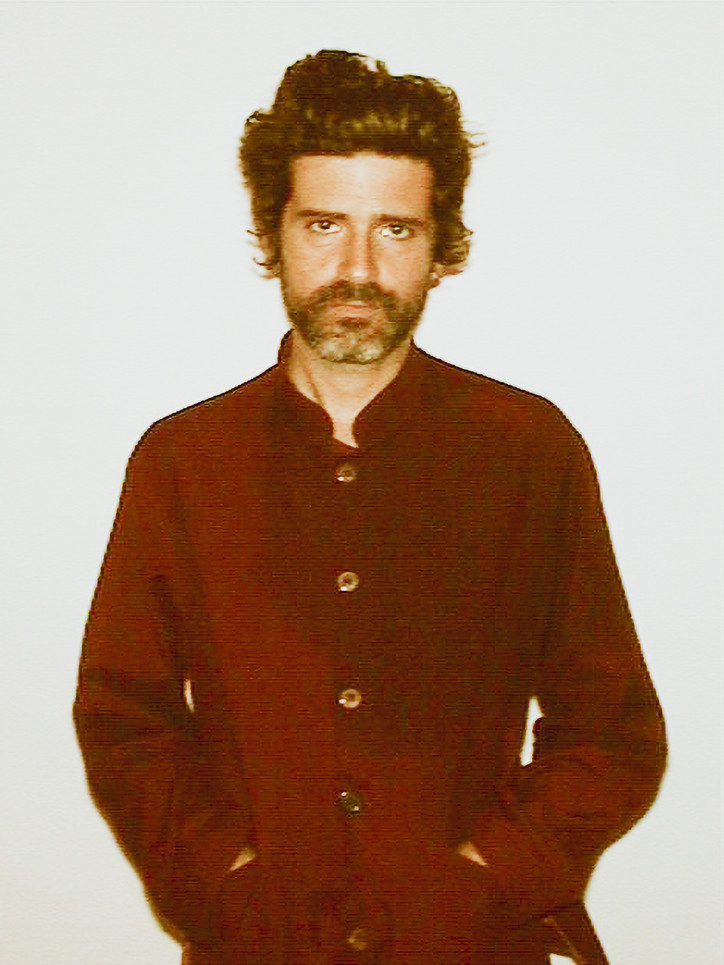

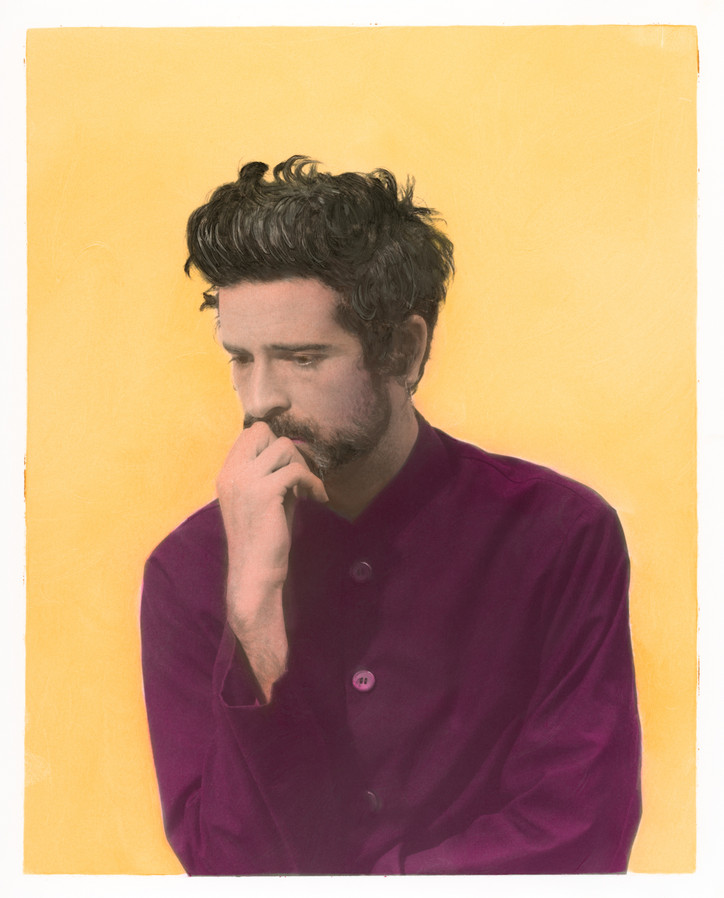

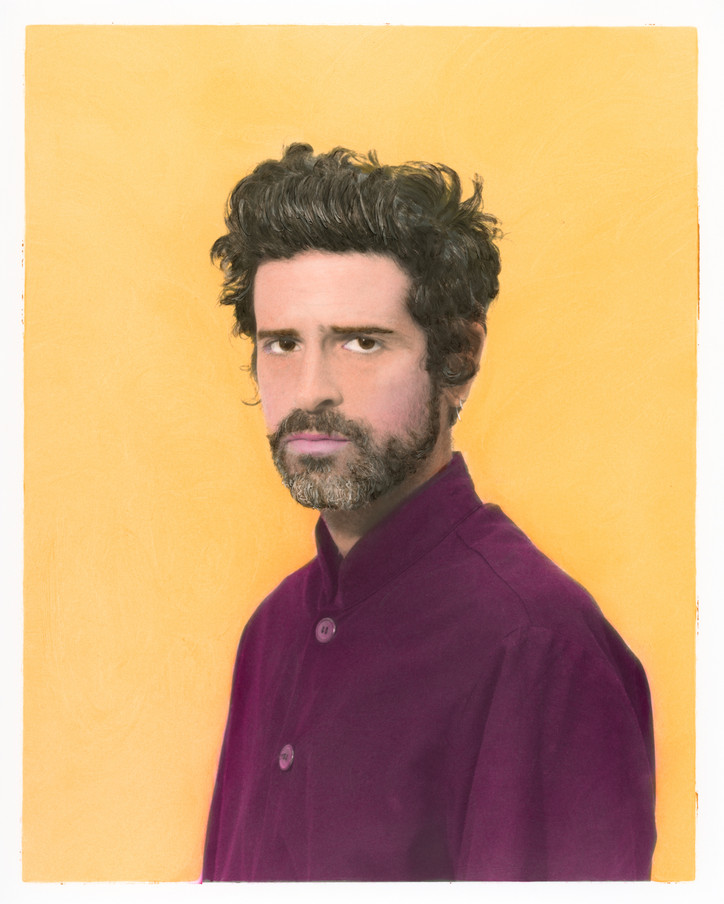

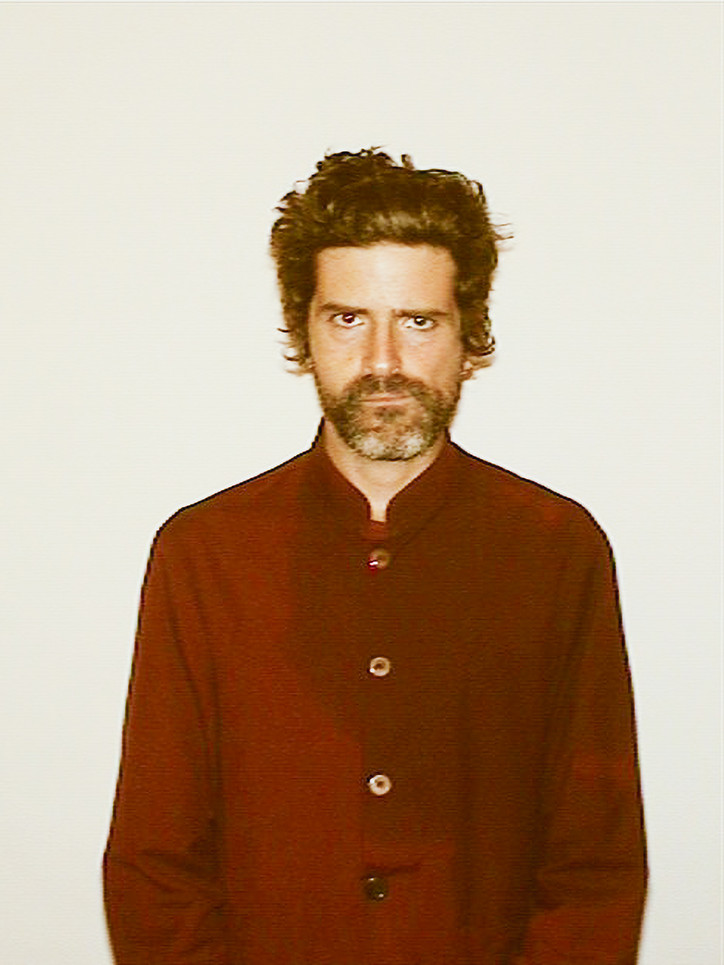

Devendra Banhart on Identity

At 38 years old, one of those lessons is that the only thing we can ever be certain of is change. “I don’t know if what I’m feeling is sustainable. Maybe that’s the answer––there’s no solid self,” he told office. “Everything I was so sure of 20 years ago, all those opinions changed. And everything I was sure of 10 years ago, those things have changed. Everything I was so sure of yesterday slowly starts to change.”

So the release serves more as an intimate caricature of who Banhart is right now, an attempt to document the moment, rather than a demonstration of what he's capable of. Departing from his standard songwriting approach, he didn’t include any characters on this record. It’s all his own experience––thanks, in part, to the solitary environments Ma was recorded in; the first, a temple in Kyoto (the recording from which didn’t make the final cut; but it “spurred the record”), and a small house on the Northern coast of California.

“I wasn’t in the city where you just walk out and see a million things and choose what to write about, or observe until there’s something to write about, which is a really rich terrain,” he explained. “There was nothing like that on this record because we were just in a house surrounded by redwoods. So you’re kind of faced with yourself.”

And facing himself for Ma meant addressing his fears and letting them lead. “If I tried to put on some front that I’m going to fight my fear, it would just grow bigger. I have to learn how to live with it in some harmonious way––I can’t kick it.” There’s a palpable sense of emotional presence on the new album, with poignant songs that look back and reflect lyrically, without overthinking, (“Memorial”), and others that revel in a very human, universal simplicity (“Love Song,” “Is This Nice?”).

Between the four languages Banhart moves through on the album (English, Spanish, Portuguese, Japanese,) the overriding language coming through on Ma is one of wistful love in all its forms.

Check out our conversation with the artist, below, and stream Ma here.

Making Ma, what part of yourself did you get to explore that you maybe didn’t when making music in the past?

That’s an interesting question. In one sense, I got to record in the most appropriate place for the kind of record I was trying to make. And that’s an incredible gift, really, to record in a setting that’s in harmony with what you’re trying to convey. I think it gets something across. We had the opportunity to begin the record in this temple in Kyoto. Our version of trying to approximate that environment was a small house in the Northern coast of California. That was an incredible gift, to record there.

The last record was all synths and electric guitars and it was all recorded in a tiny space in a pastoral neighborhood in LA. And we were making up some story about Japan in the mid-’80s in this dilapidated hotel. We were making up this story about a place that didn’t exist, so it’s a bunch of characters.

And on this record, there were none. I wouldn’t say that that’s a pleasure though, because it’s tough. You suddenly don’t have all these––you’re not writing like a bulimic ladybug or something, you know? You’re not writing as a character––I’m a neurotic cactus, or I’m a toilet, whatever it is. There are no characters. And that isn’t necessarily pleasant at first.

It seems like this record was much more of an inner journey and it was about things that you had to get out rather than observations you were making in the world.

I think the environment dictated that style of writing as well. I wasn’t in the city where you just walk out and see a million things and choose what to write about or observe until there’s something to write about, which is a really rich terrain. There was nothing like that on this record because we were just in a house surrounded by redwoods. So you’re kind of faced with yourself, and there was a kid, I’m like his auntie, Noah [Georgeson]’s son Osian was there. I’m just watching the relationship between Osian and his mom and dad, and my relationship with Osian, I was his little auntie, teaching him to skateboard and how to speak Spanish.

I’ve known the people in my band since we were little kids, and now they have kids. So I get to watch that relationship, too. And that’s become part of the record for sure. And all the while I’m hearing from my family in Venezuela. So this maternal theme started to develop, but I think out of the way that nature can act as a mirror. Because there’s not really many distractions. Go for a hike without your phone and you’ll be relieved at first and then you’ll start to get very uncomfortable, and then you’ll become comfortable again.

There are multiple languages on the album and just thinking about the theme of motherhood and parenthood, I was curious about how those things intersect, because parenthood is this universal language –– and you were experiencing it from lots of angles. Watching your friends parent and being an auntie in a way, and talking to your family about your motherland.

Well, motherhood is utilized mostly as a metaphor on the record where I’m writing as an imaginary mother to a child that doesn’t exist. If I don’t have a child this is everything I want to say to a child. While that’s happening, it strikes me that maybe this is everything I wish I’d been told. So those two things are intertwined, but it’s beautiful and I’m very grateful for music. If you’re composing music it can be a very therapeutic thing for yourself, and I think I’ve always known that.

In the past it’s been about the architecture of the songs, and how many different genres can I reference, and how can I show off in some ways too. I want to show you I’m special, I want to prove something to you. [Laughs] That’s not necessarily a bad thing––it’s about the craft of it in a way. But when you get into really trying to explore your psyche and go to an uncomfortable place, it’s a different challenge. It can really help you out if you’re not bullshitting yourself. It can be a beautiful gift. This sounds tremendously pretentious and cheesy, I’m fully aware of that.

If you use fear as a guiding light, [the writing process] can help you face your fears. There’s no such thing as killing your fear, for me, because I’m a very weak and deluded human being. For me there’s just getting to know it and there’s just learning how to dance with it and have a conversation with it. If I tried to put on some front that I’m going to fight my fear, it would just grow bigger. I have to learn how to live with it in some harmonious way––I can’t kick it.

What were the fears you were having a conversation with on this album?

It’s almost like my own are mostly rooted and related to Venezuela, especially on this record. And also to some degree, coming to terms with maybe not having a child. I have the option to be really depressed and think of myself as a failure as a human being. I could still have a kid, I know that––but I’m at that age where maybe I won’t. So the question is, can I accept if I don’t have a kid? That was the initial fear. Writing through it and making a record for a child that will or will not exist––it really doesn’t matter––and accepting that, is a really liberating feeling. There’s certainly no shortage of human beings on the planet. And the way that I can give my attention and my love as an auntie is very different that parents give to their children. When I say parents, I mean my band, my friends––all my friends have kids and I’m the auntie. And my love is not possessive. I like that a lot. I don’t have that fear anymore, it’s not about having a kid or not.

But the fear with Venezuela is prominent because it’s an ongoing thing. Imagine you have to pick up everything you own and just leave. And imagine if every masterpiece by an American painter has been robbed and ransacked and imagine that your kids don’t have medicine, and imagine you don’t have electricity, and you have to write to someone and say, “I’m not going to talk to you for a week because the power’s going to go out. Talk to you later.” That’s horrifying.

More than 4 million people have left, thousands a day are trying to leave the country, find refuge in Ecuador and Colombia, Trinidad and Tobago, the Caribbean. Right now at this moment it’s a standstill, it’s a gridlock, who knows what’s going to happen? That place is like my mother, so that’s the biggest fear on the record. Not knowing what’s going to happen with Venezuela and watching it from a distance.

Who in your family is still living in Venezuela?

My uncles, my aunts, my cousins, and my brother. My mother is not. The amazing thing is that it politicized her, this whole situation. So suddenly our conversations are constantly about what’s going to happen. They’ve always been, for 40 years, because the situation in Venezuela is never good. But nobody imagined it would be this bad. I was there two years ago and I felt like it was the apocalypse. There were these long lines just to get a piece of bread––the tension, the anger, the anxiety, the fear, the oppression in the air. I couldn’t imagine it would get worse. But it really has.

But this whole thing about fear, it doesn’t matter, my specific fears. I think in general that’s a great guiding light for what to write about or look at. But I think there’s a misconception about killing them. I don’t think you can do that. I mean, yes, I guess some people can. I take it back. This is the perspective of a deluded and stupid person, so let’s not forget that.

I know you’ve always been concerned about what’s going on politically, but I’m curious if in recent years it’s become more important to you to express these things lyrically. Because America is in its own situation where people are really afraid and in a sense, also don’t know what’s going to happen next.

A bit of both. I think that once Trump was elected, everyone was politicized. And that was the only good thing that came out of it, other than the revelation that these so-called adults can be profoundly immature and unwise and lacking in skill. And also that the electoral system is a disaster and needs to be restructured in a way that there are guidelines that need to be followed. You really cannot have someone who is that racist and negative and sexist as the president. Children are watching.

I kinda realized if you read the Whole Earth Catalog, you realize the concerns we have now have in fact been there forever. This economic injustice and environmental degradation, and how important it is to learn how to make your own stuff, and to get to know your neighbor. All of these basic things have been concerns of humans forever. But it’s really crazy to read something that’s a counter-cultural publication from the early ’70s––it’s like reading the news today. Materialism is on the rise and inequality is skyrocketing. All these things that we’re focused on have been a problem for a long time. I think it just means everyone has to contribute in a new way, because if these have been issues for so long, it just means they’re worse now.

But people are going to need something to listen to when they go to Mars, so I’m glad people are still making music.

You call yourself an auntie, why not an uncle?

You know, I wear turtlenecks. I’ve got a lime green turtleneck. I always wanted to be an auntie. My mom’s best friends were my aunties and they were always the coolest.

I love that. Auntie Devendra. Right now at this juncture of your life, what’s the most important thing about you that you portray to the world through your music?

I can only answer based on how I feel today. I don’t know if what I’m feeling is sustainable. Maybe that’s the answer––there’s no solid self. Everything I was so sure of 20 years ago, all those opinions changed. And everything I was sure of 10 years ago, those things have changed. Everything I was so sure of yesterday slowly starts to change. That’s a tangent, not really my answer.

Maybe the answer is that somebody like me, who really doesn’t like people, can learn how to have a relationship with the world.

You seem like you like people, but I believe you.

I don’t, I don’t know. I like you. And I appreciate that you endured this conversation.

Did I miss anything?

Please listen to Joni Mitchell, everybody.

What’s your favorite Joni song?

Hard to pick. Listen to “Blue.” Wow, that really feels like what’s happening now too. “Blue” is kicking my ass right now. But if I had to pick I’d choose a combination of “Both Sides, Now,” some “All I Want”––'I wanna shampoo ya,’ wow! That’s the most loving expression. It’s so intimate, I love that.