Egg Watching: Pamela Rosenkranz

As a result of these viewpoints, the artist has been linked with contemporary schools of thought such as posthumanism and speculative realism. Rosenkranz represented Switzerland at the 56th Venice Biennale in 2015, where she created a vast pool of viscous pink liquid as a reflection of beauty standards in the European cosmetics industry. At the Fondazione Prada, she built a huge, primeval mountain of sand infused with a feline pheromone that activates biological connections between cat and man.

She has also made paintings under the influence of Viagra, exploring how the nature of the work might be altered by chemicals designed to give men artificial virility. In this conversation with writer and curator Shumon Basar, Rosenkranz discusses her latest project, a robotic, AI-endowed serpent entitled Healer (Sands) that debuted at this year’s Sharjah Biennial in the United Arab Emirates.

Shumon Basar—Before we get into the backstory, it would be useful for readers to know, in simple terms, what visitors encountered when they saw your new work Healer (Sands), and where it took place.

Pamela Rosenkranz—At the invitation of curator Omar Kholeif I developed Healer (Sands) for the 14th Sharjah Biennial. Under the title Making New Time, I worked with the courtyard of the historic Bait Al Serkal building, a former maternity ward, forming the habitat of my robot snake. The courtyard was visible from all around the galleries of the building and there were huge glass windows and doors that gave a perspective to observe its behaviors, almost like in an open-air terrarium. It was not always visible, hidden behind vegetation or in a blind spot. It lay there, shining and without movement, in the sun, and all of a sudden it would silently lift its head and observe the surroundings or move sideways. Her movements were initiated and controlled by algorithms which connected to electrical noise. The visitors filming and photographing with their mobile phones and cameras had, unknowingly, an influence on the behavior of the snake. Since its patterns of movement were unpredictable, it required patience to actually see the snake move sometimes. In fact, the robot, with its enigmatic motion sequences, became a snake through the Biennial visitor who considered the behavior to be just as erratic as a real snake’s behavior. The snake invited the viewer to enter its timeline and literally was “Making New Time.” But for some, the snake’s traces in the sand were the only proof that the robot had actually explored its surroundings.

SB—What is your earliest memory of a robot?

PR—I don’t have a clear early memory of a robot in the sense of a machine that resembles a human being. The first contact of something rather opposite, that turned humans into absolving robotic actions, was Tamagotchi. It was popular when I went to school. I was not allowed to have one though. My mother made us have many pets instead. Always a dog, always two or three cats and kittens. Then, some bunnies, birds, a turtle and hedgehogs over the winter. Loads of animals. We liked them, loved them, we were devastated when they died. Horrified when the fox left us with the decapitated body. There was no way I was allowed Tamagotchi. We had to look after our real live pets. Although Tamagotchi is not a robot, it feels like the preparation for living with robots. A robot egg, so to say. The word is a Japanese blend—tamago meaning ‘egg,’ uotchi meaning ‘watch.’ So it makes you pregnant with a robot and asks us to respond with, you could say, robotic actions. Caring about its hunger and hygiene, its need to play. A robot egg that prepares us for relations with robots to come, which will inhabit our domestic spaces to care for our needs. Although I felt left out, I was mesmerized about the effort my friends would take to keep them alive. And still I find it mind-blowing that this very rudimentary digital item, with just a little cuteness and a very crude program, was enough for it to be that successful.

SB—Where did the snake idea emerge from?

PR—Now, the snake is born from an egg just like a chicken. But arriving unfeathered and slippery, it is not the cute pet we usually are drawn to look after. [laughs] It’s funny you ask about that, as I never had feelings out of the ordinary towards snakes. Nothing eerie, no special curiosity. Usually, I start with thinking into topics from many different angles to find and develop an idea. This work came into existence differently than other works of mine that have a more cerebral approach. I have had neither a phobia nor a passion for snakes until recently, when they entered dreams I had when I was pregnant. And I have to say that I usually don’t seem to dream at all—at least I don’t recall my dreams. Even before I knew I was pregnant, it started with dreams focusing on a plentitude of different snakes. I looked up the meaning out of curiosity, but with the many different snakes I would dream of, more multiplicities of meaning came with them. As I am not superstitious, and have no special weakness for the meanings of psychological symbols, to me it dealt with the miracle of the formation of a new vertebra that was happening with the onset of pregnancy.

SB—We have worked together on a previous project of yours at the Fondazione Prada. I know from this experience that you often begin with research into recent science. For your commission at Sharjah Biennial 14, was there something you had read or been thinking about prior, which you then decided, “Now I can explore this?”

PR—The snake as a symbol is omnipresent and complicated, and as I said, the very start looked a little different but then turned into reading recent scientific findings, as you describe. Research about its medical properties, longevity, and anti-aging has formed part of the foundation for the robot snake. At the same time, I got really interested in the reasons why snakes feature in prehistoric drawings, along with prehistoric predatory cats, which I have made work about before. I wondered how much this relationship is inscribed into our basic psychological and physical structure. Why do we dream about snakes even if they are not part of our urban lives? Why do we have phobias about them when they pose no threat? Snakes were drawn, cast or sculpted into the rock in prehistoric and pre-religious sites and apparently there were “mounts of snakes” that kept a religious function in many different cultures. In another, recent work, the snake, literally hard-coded, was carved in stone by robots. The snake, shaped by human hand, acts as a sign. I wanted to know how the sign is potentiated if it remains formally a sign, but takes the intermediate step into a quasi-life.

SB—The figure of the snake has symbolic connotations going back thousands of years, with the devil taking the shape of a snake to lure Adam and Eve out of their paradise shelter. Are all these meanings of the snake encoded in your robotic version?

PR—As for the monotheistic religions, as you say, the symbolic connotations go back thousands of years. But those stories are based on numerous older stories in which the ambivalence of the snake is spread. In the fertile crescent, the so-called cradle of humanity, the first written documents express the deeply rooted mythological connection we share with this animal. It was, for example, worshiped as “Ningishzida” in Sumerian Cultures more than 7000 years ago. “Tiamat” in Babylon was seen as the being at the very origin of the world, and the “Ouroboros” was the ancient Egyptian symbol for the beginning and the end of time.

SB—You’re already working on a new version?

PR—At the moment I am working on the second iteration, Healer (Waters), a snake that has come from the sea that will be shown at Okayama Art Summit, curated by Pierre Huyghe. It will imitate the reflections of a water surface, and the permeability, the transition from one to the other. Like a water surface that reflects rays of light always differently changes its appearance, but nevertheless always marks the transition from one world to the other, the shimmering snake appears, transmitter, link and intermediate being between the worlds. There the snakebot will inhabit—next to possible other designated places—the former ring of Japanese sumo wrestlers, the dohyo. This place, in Japan, is not just a ring, but a place inhabited by spirits. Yorishiro is where people and objects can be inhabited by deities and where the battle of good and evil is fought on a psychological and spiritual level. In the dohyo, the robot transcends all possibilities of its existence, as a device and animal that lives where the gods animate objects and beings.

SB—A project like Healer is based on complex technology. Can you talk about how you set about finding the teams you collaborated with, and how that working process has been?

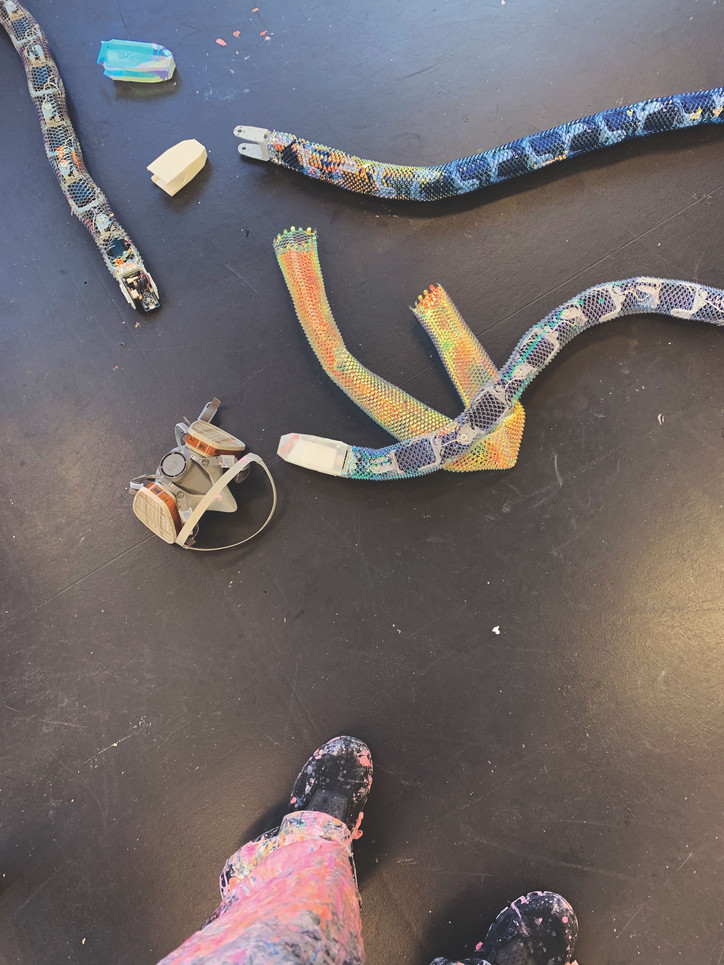

PR—There are many different developers, inventors and scientists in the academic and commercial field who deal with biorobotics and snake-like bodies in the narrower or broader sense. We realized the robot and its scaled skin with Kamilo Melo, who just finished his Postdoc at Auke Ijspeert’s EPFL biorobotics lab. Kamilo has specialized in reproducing motion sequences of living and extinct reptiles in robots. He has copied the sideways winding motion of certain snake species, such as the rattlesnake, into a complex motion sequence of the robot snake. The second integral component, the snakeskin, was from a pattern developed by Ahmad Rafsanjani, who moved from the Bertoldi Group at Harvard to ETH, and is a specialist in the field of structural design of materials. It is based on traditional Japanese paper cutting art and imitates snake scales, which are fundamental for the movement of real snakes. At the studio we worked with a team to compose the individual elements to one working organism, design its external features and make the snake bots adapt to their respective environments.

SB—We are programmed to believe scientists are rational, and artists are irrational. Is it that binary?

PR—I wish I was more irrational! [laughs] But that is very irrational of me already!

SB—How much of the aesthetic of Healer was dictated by what is currently possible with robotics? I'm presuming that there were options to either go hyperrealistic—a snake that looks like a snake in every way—or more abstract—I can imagine a Constantin Brancusi snake for example. Healer seems to be between these two extremes.

PR—The sidewinding movement to me was the fundamental element that made the snakebot creep into that gap of our understanding. I wanted the robot to remain recognizably a machine by closer looking at it, with a skin that remains constructed and see-through but at the same time functional and convincing, and slippery in an optically abstract way.

SB—For many people, the “uncanny valley” is a disturbing space. It's when artificial lifelike creations have some defining flaw to their naturalism. This flaw can become a source of horror vacui. How do you feel about the uncanny valley?

PR—In robotics, the uncanny valley describes when humanoid creations resemble reality in such an unsettling way that it is hard to discern a difference. The closer an artificial being is to the appearance of a human being, the more uncanny it becomes. It has interested me for a long time, starting as a student with Mike Kelley’s The Uncanny. Kelley relates to the idea of the ‘double’–the disturbingly realistic representation of the human figure suspended between life and death by example of the late Paul Thek’s Tomb (Death of a Hippie). I started working with that idea but in a more contemporary way, where attributes of beauty and cuteness come into play, and make it tricky. For example, I started to work with a monochromized skin color as a material.

SB—There's also a direct link between snakes and human wellbeing—various medicines have been developed from snake venom. Can you tell us more about this? And is it the reason behind the title of the work?

PR—The Rod of Asclepius symbol of international health organizations, with its snake symbol for the art of healing derived from the Greek, still symbolizes its ancient meaning as the snake symbol of ambiguity, the harbinger of life or death, adjusting to cultural changes. In times of omnipresent and fast-advancing technical progress, its contemporary counterparts seem to realize some of the historically attributed powers not just metaphorically, but literally. Snake-like mini robots enter blood vessels, insert stents or seal internal wounds. They enter the sites of catastrophes, earthquakes, or where nothing else can, and the snake’s synthesized venom has been transformed into potent life-saving drugs.

SB—Your snake doesn't bite. Was there ever a point in the development where it could have bitten? And what would robot venom be?

PR—In fact, if a poisonous snake were to bite, there would at least be an antivenom to heal it, unlike the very dangerous bite of a human being. Human saliva bears microorganisms so dangerous they would harm and even kill some not treated with antibiotics if the bite enters the bloodstream. Which brings us to the question of the robot poison because this would be, at least now, like the robot itself, a poison designed by humans. Secretion, that of poisonous snakes, but also that of humans, interests me very much. Oxytocin, which occurs in tears among other things, influences the human hormonal system and sometimes leads us to take more care of someone. In children, however, it can also promote aversion. I'm currently working on an AI animation that provokes emotions evoked by painted tears.

SB—There have already been auctions of art made by robots. Creativity seems to be one of the most important ways roboticists feel they can prove ‘intelligence.’ What do you think of this idea that making art is a hallmark of advanced sentience?

PR—The quantification of consciousness through the creation of art is super interesting, but having them make art is something rather utopian still. That art at auction at present is still a joke, rather, and not great art if art at all. I still see the greatest advantages of robotics in the fact that it gives us more opportunities and freedoms to have more and better art made by human beings.

SB—Is Healer capable of making art, in addition to being art? If you asked your scientific team to add that feature, would they know how to do that?

PR—I don’t think so. Getting the snakebot to be art was exciting to them as it would potentially bring new insights and progress along the way, but it was also an opportunity to play with it. One feature of how the sidewinding movements would come together with the skin-scales and a classical idea of art, was the traces Healer left in the sand.

SB—If you could be perfectly cloned, would you want to see the result?

PR—Definitely. If that were really possible, I would certainly accept the cooperation of a second self in the studio. But not necessarily have breakfast with it! —END