The Exquisite Experience of a Color: Glenn Ligon

"NOTES FOR A POEM ON THE THIRD WORLD (CHAPTER ONE)," 2018

Like most artists, I started out hoping I would have something to “say.” Something spinal enough to make your eyes widen as your neck snaps back from the page. Squirmy enough to make your feet creep inward and pigeon-toed under the table. While in the process of finding my voice, I realized I had become a messenger for someone else, an intravenous therapy administering the claims for some cause or another, writing to tell the stories of those in need as opposed to needing to share something about myself. The work of Black artists is often the work of service to Black stories, as is the case for Glenn Ligon; Our wretched history, discriminating pain, our God rearing hope. As artists and Black men in White America, Ligon and I also share the disorder of a double consciousness. We “stand-in” for our community, whenever we stand out, and we’re perceived as threats to be put down wherever we show up. In both circumstances, the stakes are highly charged, though in the latter the charges are routinely dropped.

"Notes for a Poem on the Third World (Chapter One)," 2018 on view at Regents Projects LA (2019), figures two giant neon hands raised at 84 x 155 inches, mounted on the back wall in the gallery’s second room. Ligon has applied a layer of black paint to the face of the neon tubes, which consequently throws a ‘shadow’ of escaped light back against the wall producing an outer glow. The large-scale sculpture is in fact a trace of Ligon’s actual hands. Their painterly, adolescent line calls up the act of tracing one’s hands as a child when learning how to draw. In this way, he offers no fingerprints to mark his DNA. No major or minor lines of the palm to determine his health, a path his life will take or the depths of his intelligence. No lifeline, headline or heartline for some esoteric palmistry zealot to speculate. What his hands lack in forensics they provide in language. They shout, anxiously, “HANDS UP, DON’T SHOOT!” and in their startled angst give shape to too many wretched bodies that have echoed through the hearts and minds of a vexed diaspora.

These hands are painted black, like me. Raised high against and swallowed up into a vacuum of whiteness, also like me. Like two mirrors set face-to-face to reveal a number of images in infinite, Ligon’s hands draft a domino line of reflections. In his hands I see my own, in my own I see the outstretched hands of a community.

TURBULENCE

"Notes for a Poem on the Third World" is Ligon’s first figurative neon sculpture. In offering this work as a figure, it embodies the formal readings of a painting. By way of analogy, Gregg Bordowitz states in his analysis of a text-based painting by Ligon, "Untitled (I Am a Man)," 1988, “The great challenge a painter must meet is to distill motion into a significant form so that the viewer may sense, feel, and anticipate all the possibilities of motion suggested by the formal elements of the painting. Through line, color, and composition, the artist creates a compelling sense of turbulence, strongly felt by the paintings viewers.” He goes on to describe how “turbulence” is experienced in a third space, a space of thinking and making connections, mediated by our existence before we encounter the work and our relationship to it and the world after we leave it behind.

Applying that logic to "Notes for a Poem on the Third World," my third space draws up the figure of Michael Brown, an unarmed black teenager who was shot and killed by a white Ferguson, Missouri police officer on August 9, 2014. That shooting mobilized a community into protest, transforming Brown’s show of surrender into a weapon of resistance and a national movement that rallied behind “HANDS UP, DON’T SHOOT.”

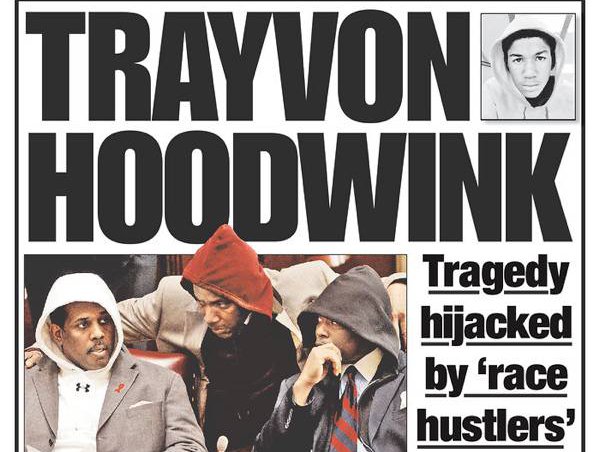

It reminds me of my dad Bill Perkins, then State Senator of New York. His signature fedora replaced by a hooded sweatshirt, flanked by Senator Kevin Parker and Eric Adams, who were also wearing hoodies as they walked into the senate chambers on March 26, 2012. They chose to wear hoodies on that day in solidarity for the family of Trayvon Martin, the 17-year-old who was shot in Florida for wearing “suspicious” clothing. Lampooned on the cover of the New York Post the next day, that photo is framed by text, scandalously, “TRAYVON HOODWINK. TRAGEDY HI-JACKED BY RACE HUSTLERS.”

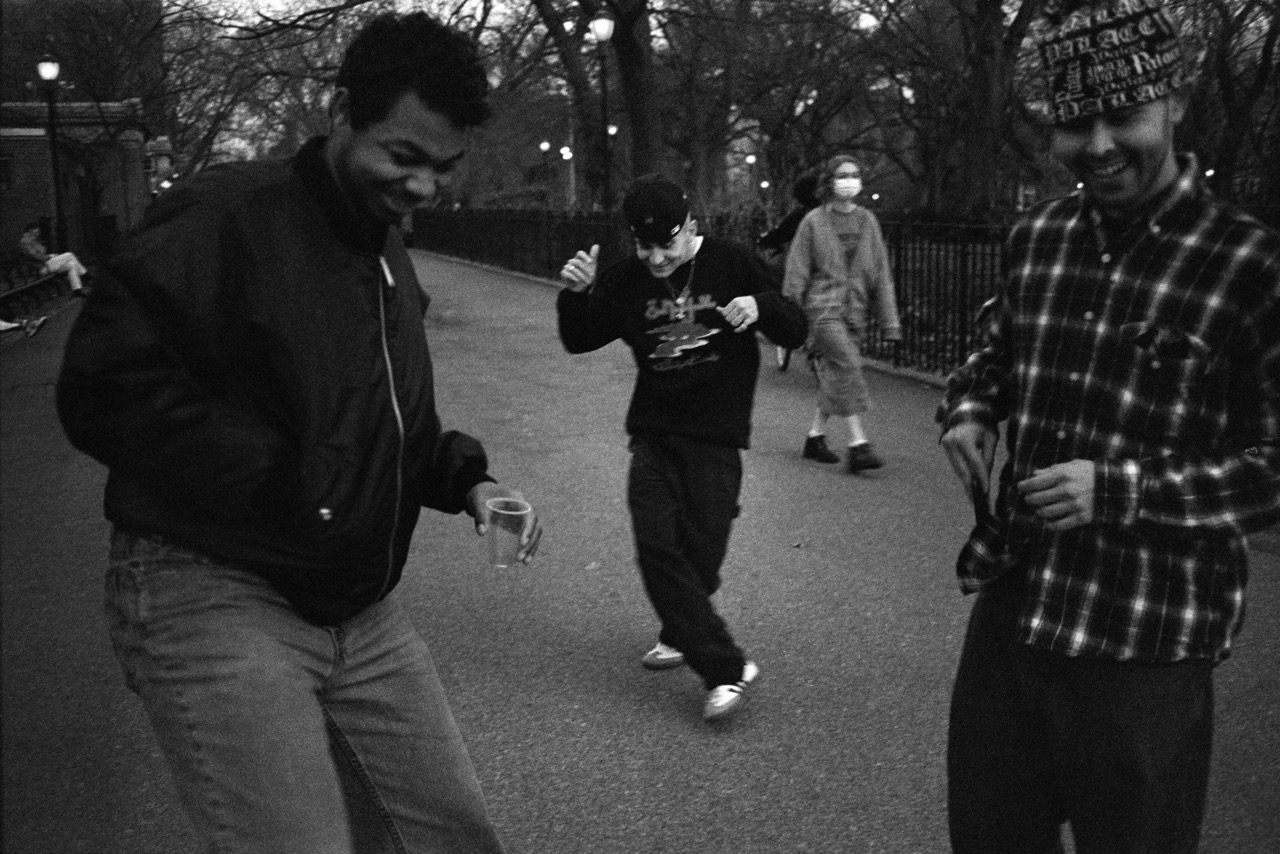

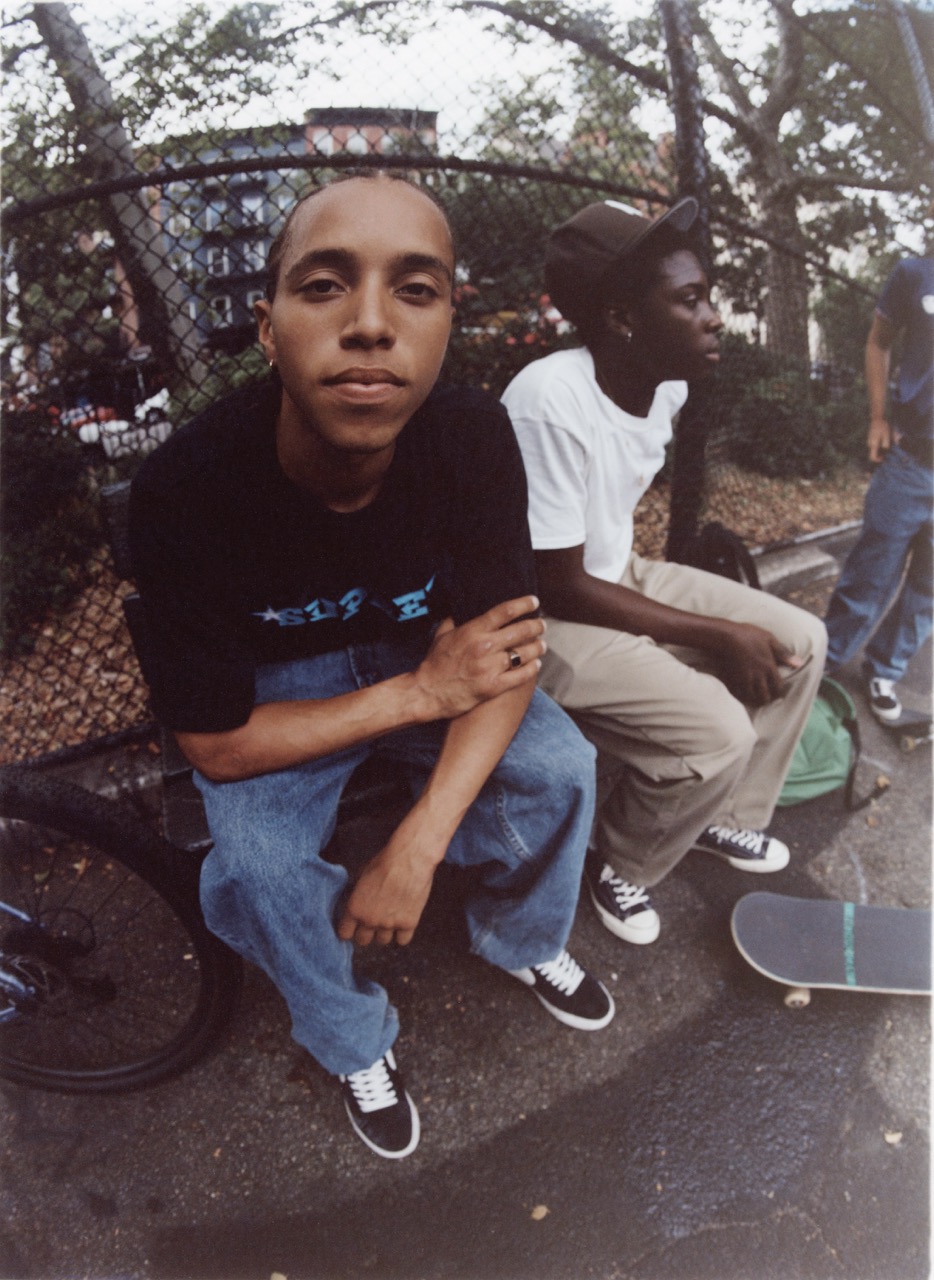

But I’d be damned if the souls of those ghastly bodies don’t dare to groove and shake. Together, Michael Brown, Trayvon Martin, my dad, Senators Parker and Adams, dance out their rage to the Congo drum of Busta Rhyme’s “Put Your Hands Where My Eyes Could See.” They pose centerfold in the juicy wet melee of Hype Williams’ fisheye lens.

My third space is a black space. A double consciousness of both trauma and redemption. Where adversity is re-imagined as opportunity, transformed into a feat of endurance. This is how Blacks in America make Life Matter.

NOVEMBER 3, 2020.

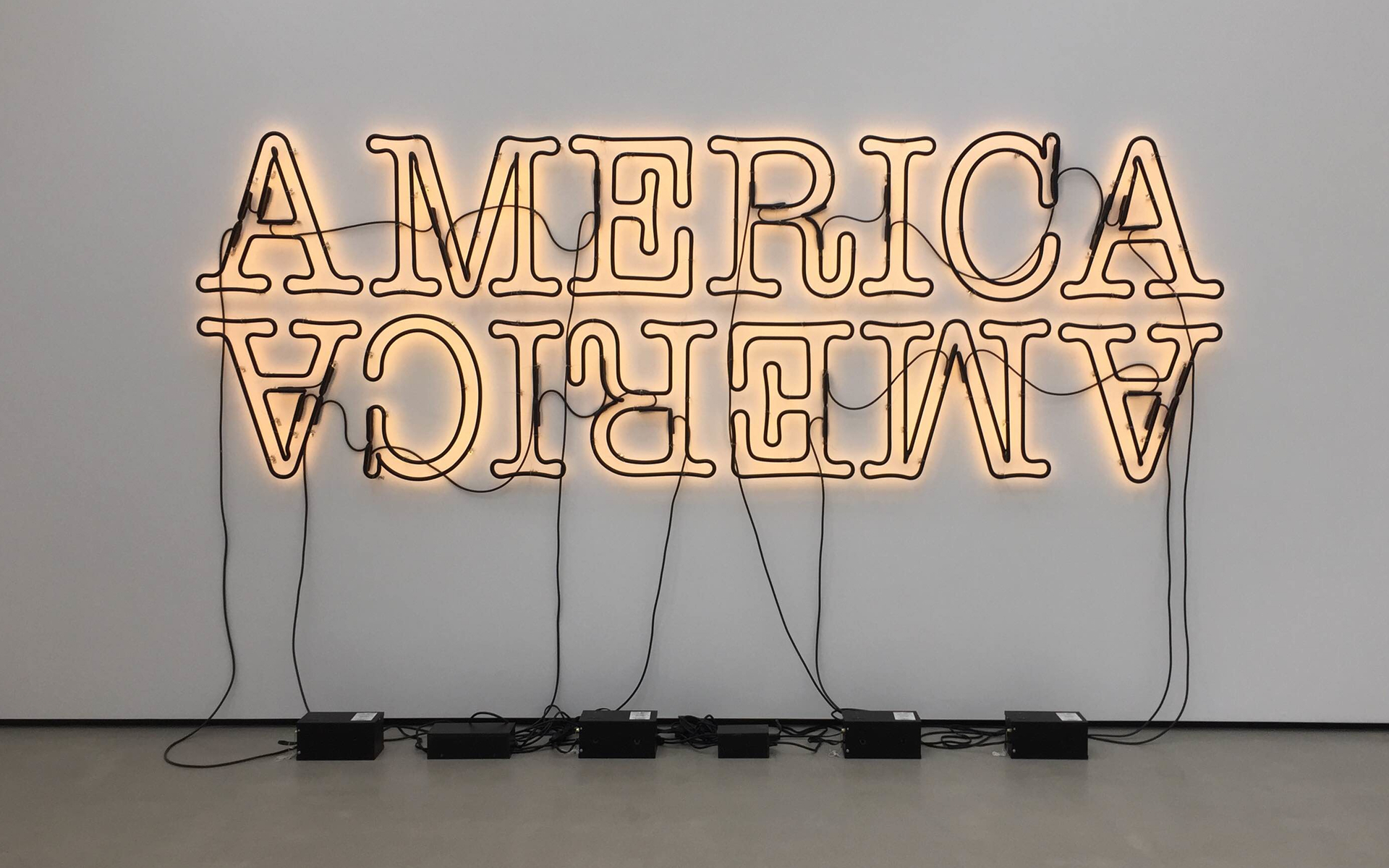

Mounted opposite "Notes for a Poem on the Third World" is "Untitled (America)," 2018, a black neon sculpture painted red that spells out the word 'AMERICA.' Displayed upside down, this work builds on a series of neon sculptures that also spell out 'AMERICA’ in large capital letters of a light-weight typewriter script, a letter form that also appears as a stencil in Ligon’s text-based paintings. Each individual letter in "Untitled (America)," 2018 is comprised of a single neon tube mounted against a white wall as if free-floating. Two electricity cables looping through the letters form the only visual and structural connections between them. The cables drop neatly to the floor and along the wall to intentionally visible power supply units. In other sculptures, ‘AMERICA’ has been spelled backwards ("Rückenfigur," 2009), and also backwards and forwards in "Double America," 2006, with two stacked 'AMERICA' sculptures presenting a mirror image of each other.

Born in Bronx, New York in 1960, Ligon is best known for text-based paintings and neon sculptures like these that draw inspiration from literary works by writers such as James Baldwin, Zora Neale Hurston, Ralph Ellison, Richard Pryor and Jean Genet. He redirects excerpts from their texts to resurrect new meaning; to reveal the ways in which the history of slavery, the civil rights movement, and sexual politics inform our understanding of America. In the 'America’ series, he splits the country into two, exploring the dualities found in a country that has become increasingly bifurcated along social, political, sexual orientation and economic lines.

Described by curator Scott Rothkopf in the catalog for Ligon’s America exhibition at the Whitney Museum of Art (2011), "AMERICA (2006) looms large and powerful, yet its letters are thin, open and permeable suggesting a national portrait of the country’s power and fragility.”

"Untitled (AMERICA)," 2018 corroborates another truth. Also looming large, hung upside down, it reveals America’s unchecked anger, hell hot and boiled over. "Notes for a Poem on the Third World" is pushed up against the opposite wall, nails chipped as America casts its shadow. From darkness, the whites of our eyes illuminate motifs bound to the metamorphosis of the exquisite experience of a color. From chained bodies, hanging nooses, German Shepherds and firehoses, to our outstretched arms and hands. The national portrait of Black life in America today.