Ferngully

office spoke with the Haas brothers about their start in construction via cabinetry, their interest in sexuality and fancy furniture.

Tell me about your work.

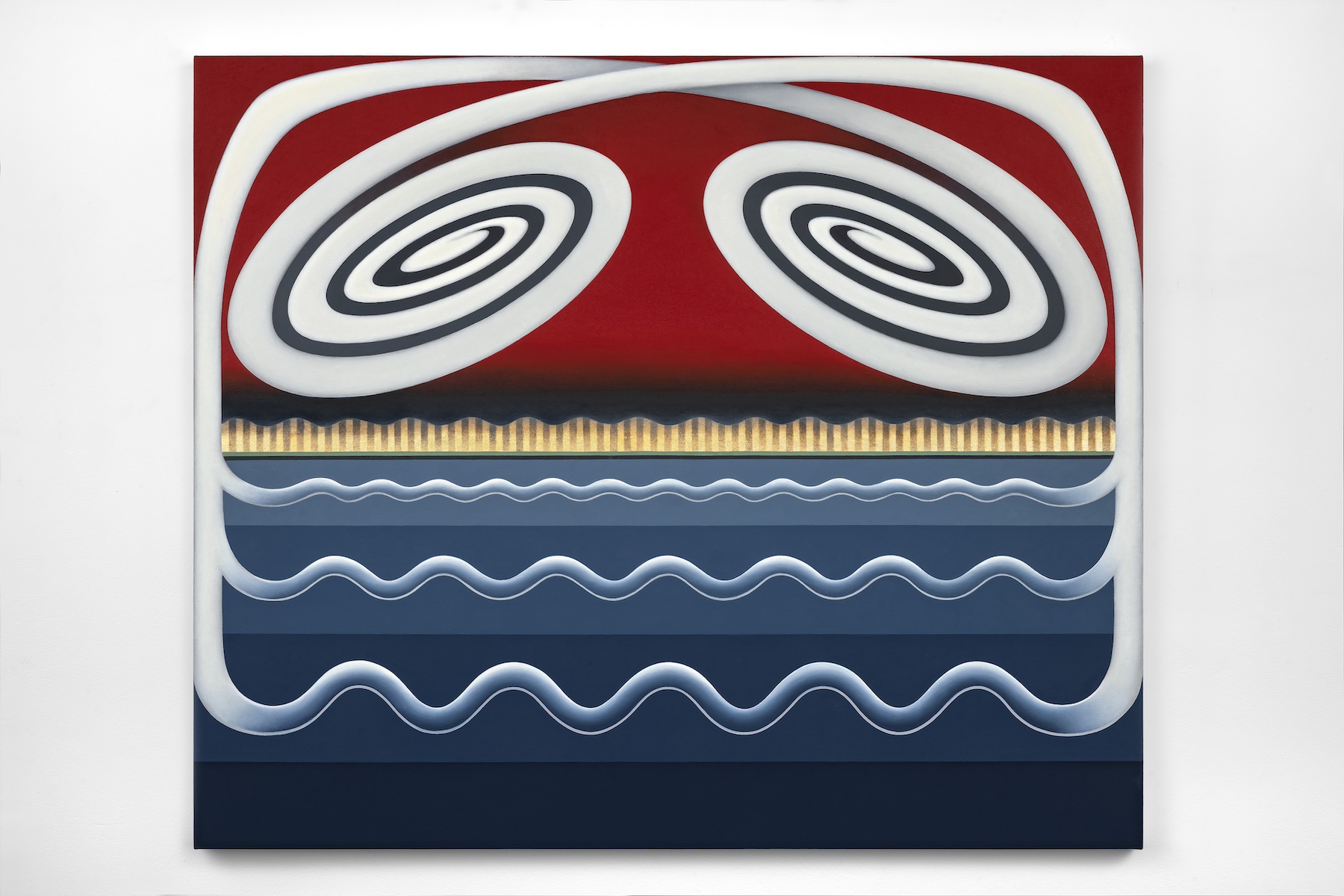

Niki Haas: The show is sort of an exploration of our childhood until now through the use of the pieces we’ve made throughout our career. When you walk into the show, you see the earliest things we made together; then in the middle, there’s a different body of work; and in the back, you’ve reached what we would consider the future of our studio, where we’ve made a couple pieces specifically for this show, and represent the way we want to make work from now on. The show is really about Simon and I, and our relationship—it’s about the work that our relationship creates. It’s nice now that we’re in our early thirties, and you can look back through our career and see how accurately the work marks time in our lives, from our viewpoint, and you can see, whether we meant it or not, exactly how we were feeling and what we were thinking at that exact point in time. This sort of this arc.

It’s like an autobiography.

Niki Haas: Exactly.

Simon Haas: It’s like a diary. The work holds a mirror up to ourselves, but I don’t know if anyone else will necessarily get that out of it. But our work is really influenced by how we’re feeling emotionally and psychologically at that time. So, when we look at them, we say, 'Oh wow, that’s what we were thinking then.' So, it’s a cool exercise for us.

Niki Haas: We had the opportunity to spend a bunch of time together recently, and over the past few years, we went to therapy to try and understand our relationship, and who we were as individuals, but also how we relate to each other. As twins, it’s obviously really important, the influence your twin has over your life. That’s where the title comes from—Ferngully—it’s because lots of pieces of the work in the show are loosely based on characters or things we remember from childhood. So, Ferngully is what that’s all about—diving back into our psyche, our childhood and who we are.

I only know the movie by that name, the cartoon—is that what you’re referencing, or is there more to it?

Simon Haas: No that’s it. We watched it a lot as kids and were kind of obsessed with it. We draw on it a lot as a reference, even the way we name things has a lot to do with Garbage Pail Kids, which were another big part of our childhoods. We bring our childhood influences in a whole lot, and Ferngully made sense for us because we’ve created a kind of small jungle scene in the back and we’re just really obsessed with nature, both plants and animals. It’s silly, but I think that we went through our own Ferngully moment—we saved ourselves from obliteration, if that makes sense, and then came out on the other side. The last few years have been characterized by a lot of struggle, but not work related.

Niki Haas: For example, take a moment in your life—not something that’s necessarily embarrassing, but say a really bad fight that you had with a loved one you want to express out in the world, but the details wouldn’t even be interesting or engaging to somebody that was outside of your realm. So, for us, what we do is create animals, and plants, and environments that sort of act as parallel realities to what's really going on. Things inside of us just spring out. The idea is to create an alternate reality with things that don’t actually exist—none of the animals are real, none of the plants are real, but it creates an environment, a vibe that takes you where we were when we created the work. The point is to transport you into this realm of thoughts and feelings. We’re known for doing that, we’re always creating Ferngullys, and this is sort of the biggest version of that so far. It’s almost like our inner demons.

It reminds me of Big Mouth, have you seen that?

Niki Haas: Yeah, Big Mouth is great—the hormone monster.

Yeah it’s like a physical manifestation of something very real and problematic.

Niki Haas: Big Mouth is a perfect example—I personally think in cartoons all the time. If I don’t know how to make an emotion make sense inside in my head, I usually relate it to cartoons or ice hockey.

Some of the pieces even look like the hormone monster! Now some of it is furniture—or is it all furniture? And are they designed to be functional pieces of furniture or are they more pure art objects?

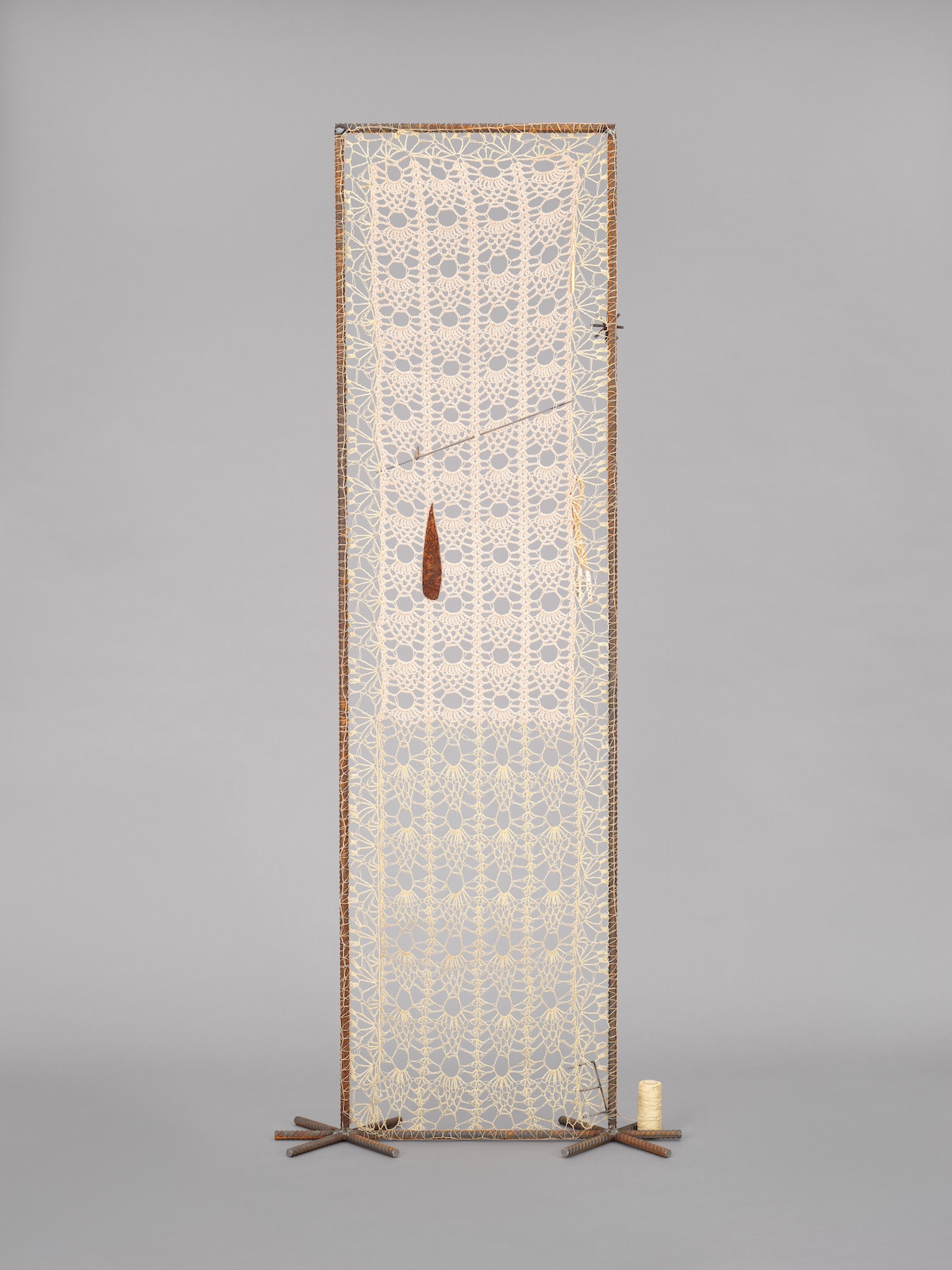

Simon Haas: Some of it has the intention of being functional, but we also make sculptures of chairs that you can’t really use. We came up through the design world, but we’re not limited to that. A lot of people call us designers because it’s simpler, but most of our stuff is useless. Our ceramics are a good example—it is technically a vessel, where it’s a nod to ceramics as an art form historically, and it’s supposed to be a vessel, but we use that to make something that is so unusable that if you try to use it you’ll actually destroy it. To me, that creates a tension that I really like—you want to use it, you want to pick it up, but it’s just not possible. We’ve always flirted with that—we use the language of design and the language of art interchangeably, and usually if design is involved, we’re using it with a purpose, to subvert what you would normally think of a chair as being, for example. But not everything is functional, and even if it has a function in name, it’s unlikely that it’s that usable. If I were to purchase one of the pieces I probably wouldn’t sit on it.

Niki Haas: People do, though.

I love furniture like that—that you buy and never sit on, like old, super fancy furniture that’s too beautiful to actually use.

Niki Haas: And by the way, we do make designs, that’s one of the things we do—we do many, many types of things, and if somebody calls us ‘designers,’ I accept that with pride. We’re definitely capable of creating a chair, or a table, or whatever it is that you might want to use. But the way our career happened was, we started as construction workers—we’ve been doing construction since we were kids, then Simon and I opened our studio as a cabinet shop, or a carpentry shop. That turned into high-end design, and then that turned into art. This is really our biggest moment of, ‘Hey, we’re artists,’ because we’re showing in an art museum, but we’ve been doing this for a while and it’s really about the evolution of what we’ve been doing all of our career. It went from, 'I want to build something that someone else designed,' to 'I want to design and build something that works for someone to use in their home that’s beautiful,' and then that became, 'We want to make designs that subverts their use and questions what it is, like what is that actual design piece?'

Simon Haas: It doesn’t have to be functional, which is nice. It gives us freedom.

Niki Haas: Then that became, 'We want to utilize our platform to talk about social and political issues that matter to us to engage and support communities that are in need, and to do things that are healing the world, or at least our version of healing the world.' That has become one of our main focuses. I guess it just depends on what you consider an artist, but to me, an artist is someone who is exploring social realities, who’s trying to relate to the world and understand their place in it, and is making work that interacts with those thoughts and feelings.

What social issues does your art engage with?

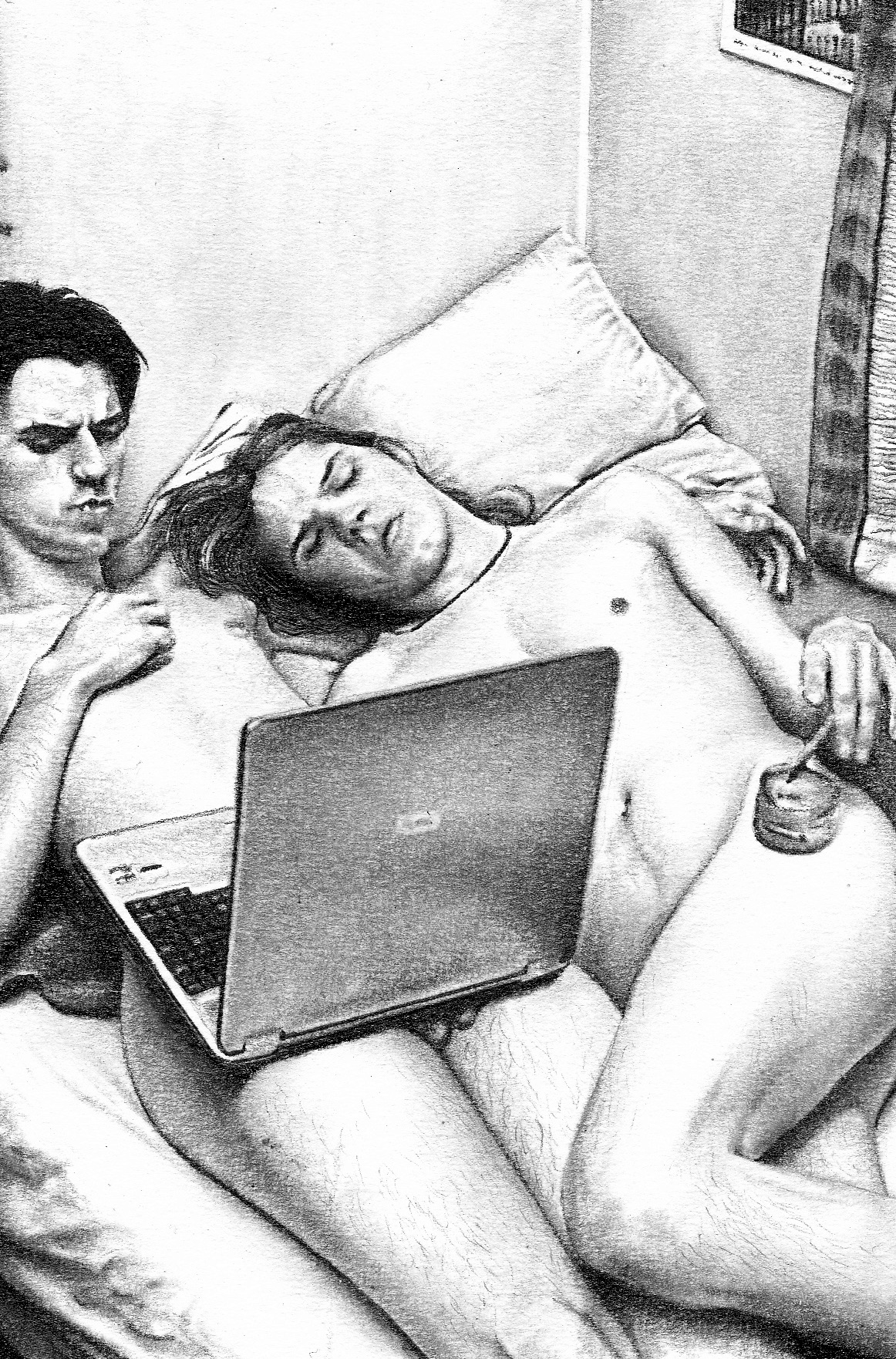

Simon Haas: A long time ago, we were focused on shame as a social problem. Because a lot of our early pieces had overt sexuality in them and we sort of encouraged people to interact with, for example, a penis that was on a chair. Another example would be when we made a room that we presented at Design Miami a long time ago where you would go in one at a time and feel all of these sex toys, and a video of a male and female where the male is more sexualized, I think. So, we started out that way—that sort of came from my own struggle with being gay and growing up in Texas, and Niki’s interest in sexuality as well, and we were thinking about that and it found its way into the furniture. So, that’s where it started.

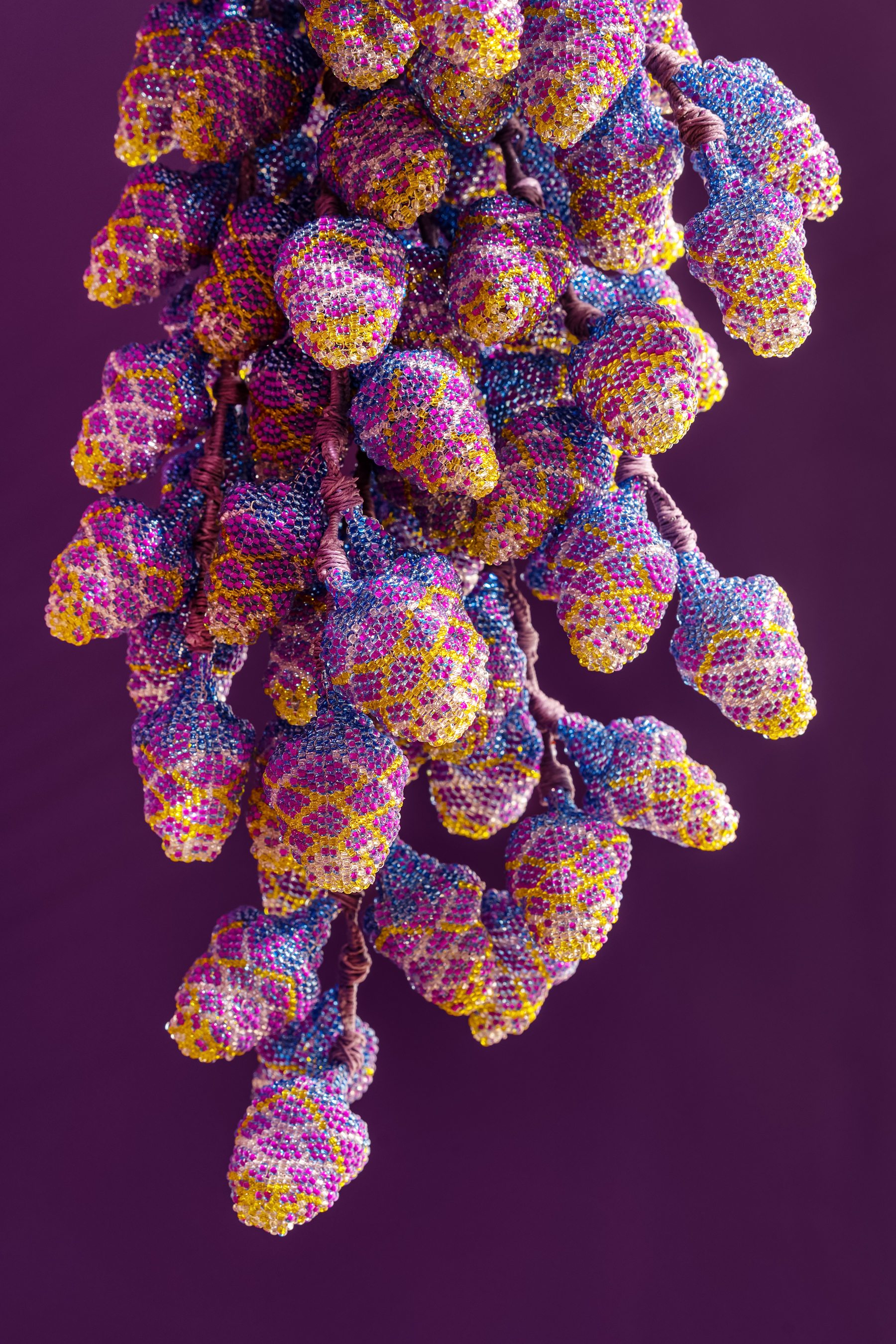

Then we went to Cape Town and we started a project there with a group of women who do beadwork and it was really enlightening. I think it sort of pointed out—and I don’t want to sound too ‘white guilty’ here—but I personally was kind of crippled by white guilt when we went there, because I just had never experienced something like apartheid in South Africa. So, that threw us for a loop, and it made us consider ourselves a lot—like, are we successful because of our gender, our race? All of that stuff. But we tried to look past it to continue to interact with and employ these women in Cayo La Tia.

Niki Haas: Also collaborating with them, not just employing them And they get paid really well.

Simon Haas: They get 20% of the sale of each object, even after having gotten a much better salary than what they’re used to. So, that’s an important part of that project for us.

This is for this current project?

Simon Haas: Some of the pieces in here are from Cape Town. But the current project is being done in California and our friend, Linda Resnick, saw what we were doing in Cape Town and suggested bringing it to the Central Valley of California. She explained to us that in those farming communities there’s sort of a vacuum for work for women in general, and she loved that we had designed pieces that could be taken home as homework, and it’s low-impact work, it’s craft. So, we brought beadwork out to California, which is cool because we learned from the women in Cape Town how to do it, and that project is still happening, and we try to share what craft can do, basically. I think that beyond the employment part, it’s really therapeutic to make things and to see yourself as an artist. The women in Cape Town had an equal hand in creating their pieces with us, and those were in the Cooper Hewitt, which was really exciting. And the women we’re working with now in California can say they have pieces in a museum in Miami. So, we try to engage with communities like that as much as possible.

Niki Haas: And we’re not just having fabricators make it—we’re working openly with them in the design process. We have a team in LA that helps us make our work, and we do it all together, and they absolutely have creative input. We have a team in South Africa that helps us make our beaded stuff, and it’s 50/50 when it comes to producing the actual pieces. We’ll do the drawings, we’ll learn about the process and do everything together—it’s not like we’re just speaking down to them and having them make whatever we tell them to. It’s about pulling people into the creative process, it’s about empowering them. We were art fabricators ourselves for a while when we had our cabinet business—we would build art for artists because we just understood construction so well, and oftentimes it was like, ‘Don’t come to the art show, I don’t want you there, you can’t tell anybody that you made the work, sign this NDA, this is my process, my thing,’ and we were building these pieces from the ground up. Sometimes, it was a lot of work, even conceptually—we’d build them from top to bottom and they would call it their own.

Simon Haas: That’s actually pretty common in the art world.

Niki Haas: True, but I think just being on that side of it, we were like, 'You know what? More than the money, one of the most empowering things you can do for someone is give them credit for building something that’s been in a museum'—that’s a huge thing.

Simon Haas: We’re artists and we’re also a business, and I think part of what we want to do, at least as a business or people who generate income, is to maybe set an example for people who aren’t making every single part of their own work, or as a company, to look to places to where the money is actually going to make a really huge difference, and try to bring economies to places that can use them more. What we get out of it is, we develop really incredible relationships where we’re taught things. This woman we met in Cape Town taught me how to bead and I swear I haven’t gone a day without beading for almost five years now because I became so obsessed with it. And one of the things we do is, we’re constantly putting ourselves in these situations because we know there’s so much to learn and be inspired by—we never know what that’s going to be, and it might really fuck us up emotionally, because it’s not an easy thing necessarily, but it’s always so fruitful.

Niki Haas: Put yourself in our position, would you be more proud to be like, ‘I’m this genius up on top of a hill who made all these pieces all by myself,’ or would you rather be like, ‘I was able to meet all these rad people and able to support and help develop and be a part of these amazing communities,’ which we have many of now, and we’re really all one big family—that is the heart and soul of the art. It’s not just a one-liner, it’s about our relationships, it’s about community support, it’s about exploring things and thinking about things in our personal lives that might be difficult for other people to express and try to like help people experience those same things we’ve experienced that have led to these more positive versions of ourselves, at least from our standpoint. That’s what the work is there for. So, we’re not just making something for someone to sit down on. It’s something that makes you learn something about yourself from looking at it and engaging with it, or even if they just laugh and have a good time—that’s what we’re looking for, a reaction that’s human, not just technical.

It’s sort of emblematic of a shift in the art world and the way artists are seen, in general. I’ve noticed a lot of collaborations these days instead of the lone genius. There’s just no such thing as that anymore—it doesn’t exist.

Niki Haas: I think our generation is just more about community, more about ‘We can all do more together’ as opposed to ‘I’m so smart, I can take something that already exists and make it more valuable just because I’ve interacted with it,’ which is a rad, out there concept—it’s very heady and all that. And from my perspective, I think the world is staying very heady, it’s staying very analytical, but it’s also becoming much more generative, and much more expressive, and I think that young people are interested less in curation and appropriation, and more in new things that don’t exist yet, and banding together to understand what a lot of people together can really do. It’s something that we’re not learning from our politicians, we’re not learning from our governments, so I think it’s in the hands of creatives to be talking more about coming together and doing things as a group, and thinking about our emotions, and thinking less selfishly about the world—that’s all of our responsibilities at this point.