Handcrafted

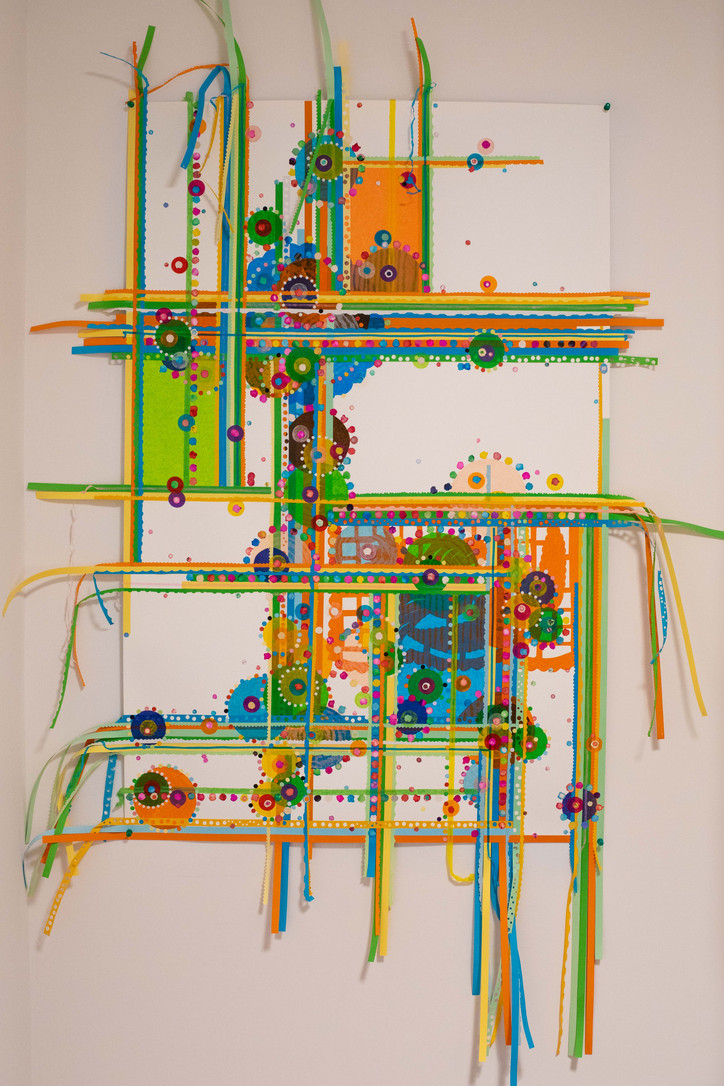

Amezkua grew up “completely bi-cultural,” as she puts it. Her parents immigrated to California from Mexico in the ‘70s, giving the artist an opportunity to experience both places in full as well as lending her a unique undertsanding of identity that has come to be an integral quality of her work. Although Amezkua didn’t take art classes until her freshman year of high school, she had been working on her craft since she was a kid, taking in practices from both cultures.

office recently had the chance to step into the colorful, multicultural world of the artist Blanka Amezkua. Read the interview with the artist below.

Can you speak a bit about the concept behind the “Re-Konztrukt” series and working with the comic book artist Luis Sierra?

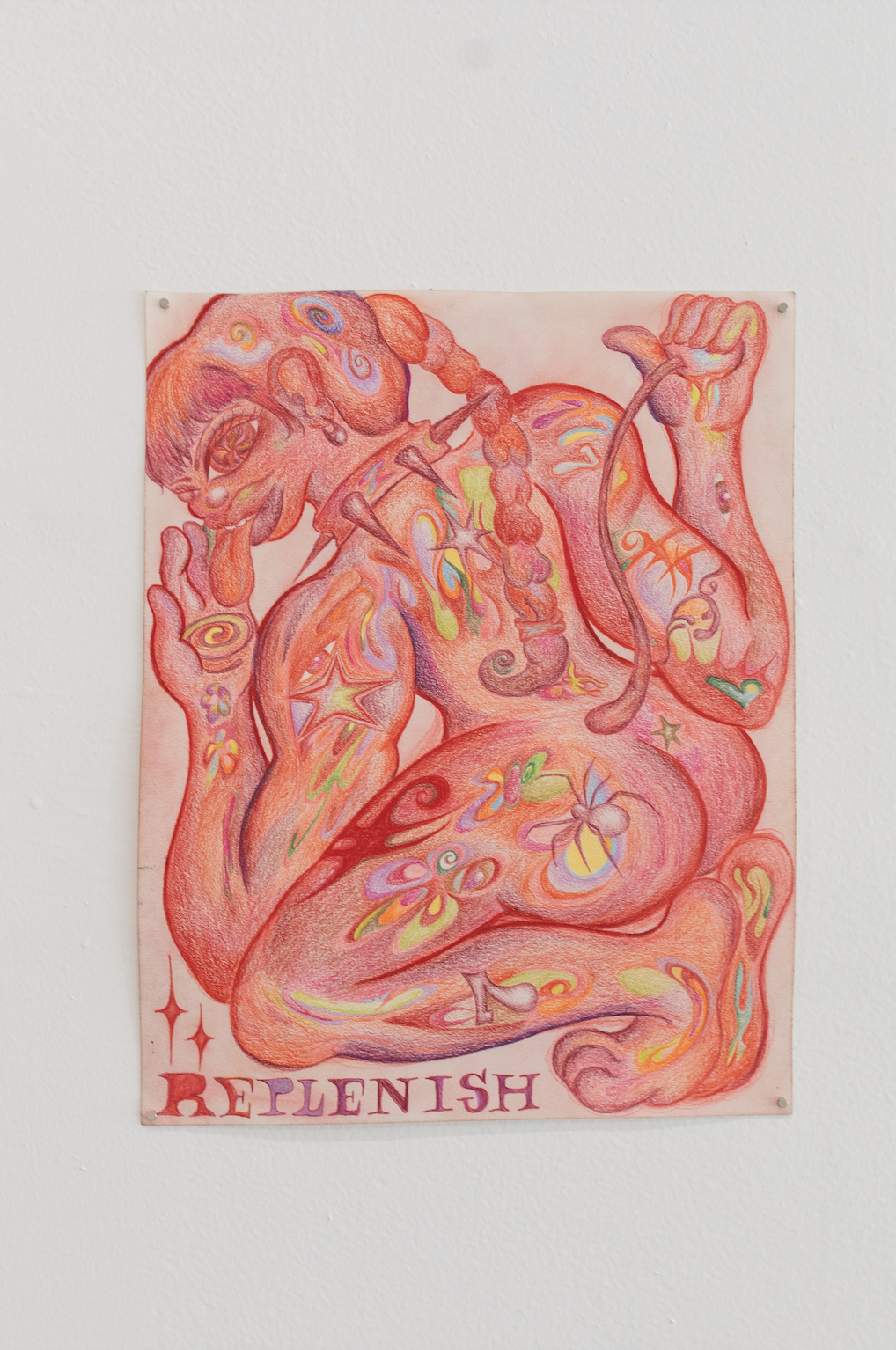

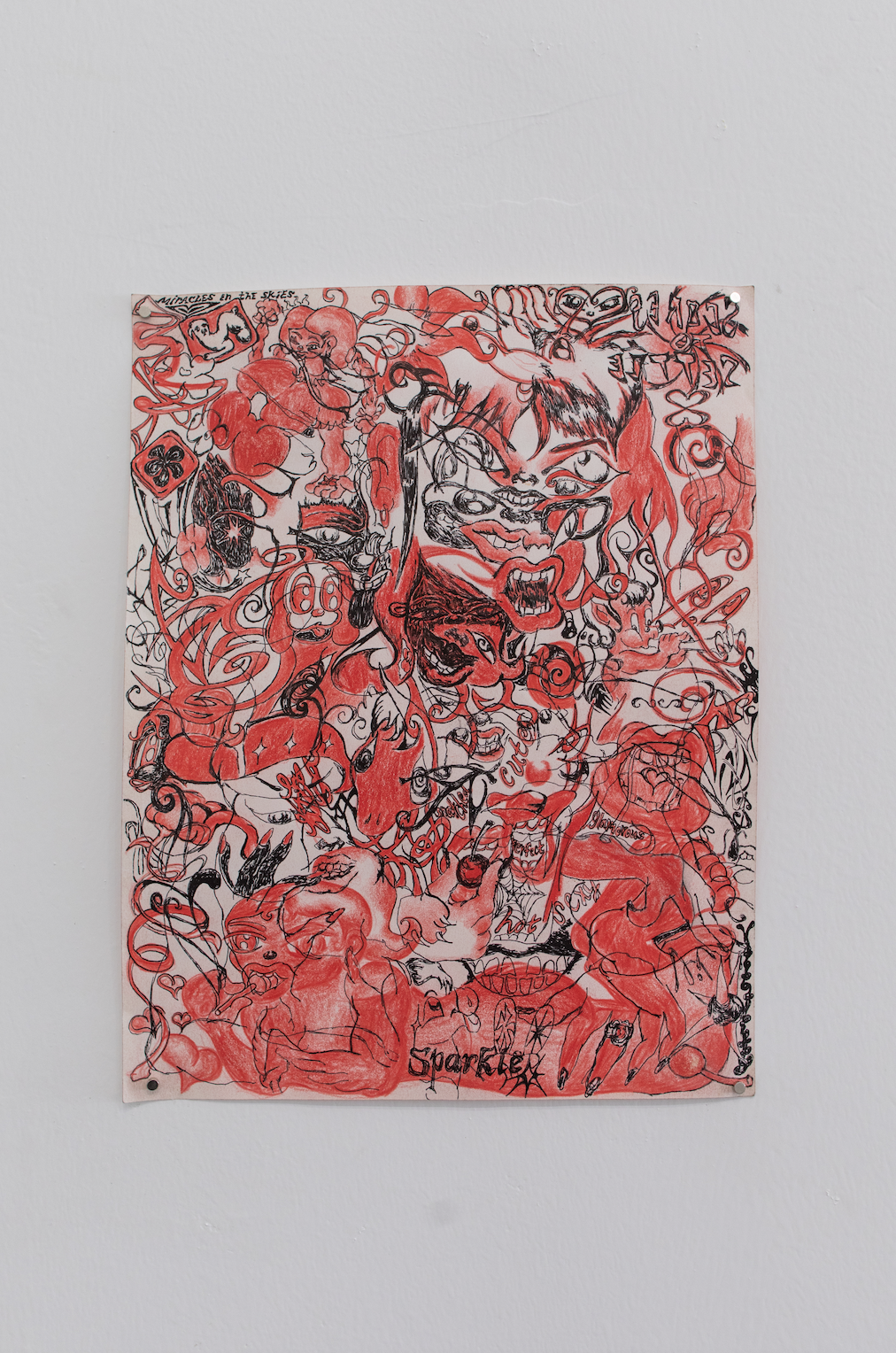

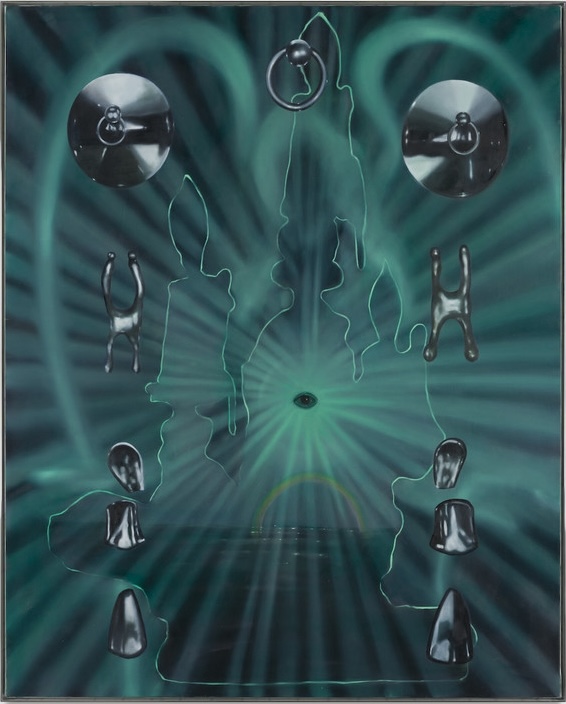

I have been working with the female imagery found in Mexican adult comic books, so when I met Luis Sierra, a comic book artist from the Bronx, I asked if he wanted to collaborate. He agreed to it and we started thinking about how to present the women in our pieces. So I suggested the idea of tools because women physically transform the world but usually you don’t see women holding these tools.

How did you switch from painting to embroidery?

Painting needs a lot of space and there are a lot of technicalities that need to happen in order to do it. When I made the transition to embroidery, it was not difficult because it was something that I could do anywhere because my grandmother had taught me how to embroider when I was about ten years old and we did some in school. In junior high, we could either take an electricity, technical drawing, sewing, or typing class. I really wanted to do electricity but there were only boys in that class and my school didn’t allow me to take it, so I just chose sewing—we learned embroidery in that class as well.

Also, in Mexico when we warm up the tortillas, we put them in a little piece of cloth, servilettas, that we embroider with flowers and different things and crochet the edges. So when I transferred that idea to this, it was basically the same thing. I even used the same fabric that we use for the tortillas to make these pieces, which were actually done in collaboration with my mother because she crocheted the edges of the fabric. Collaboration is a big part of my work.

Embroidery used to be strictly regarded as “women’s work,” is that a convention that you interact with when creating?

When I started embroidering I also realized that it tends to be seen as a very female and domestic technique but as time goes by, I see men doing it too. It still has that stigma attached to it, that it’s something crafty and domestic, but I think it’s changing.

What is it about New York that draws you in artistically-speaking?

The diversity in every single aspect. Not only the diversity of the people, but the diversity of things available, the diversity of the possibilities and things that go through New York. I feel that New York has an energy that's very specific to the city. We all create that energy and it becomes what it is because of everything that we all do. So when communities are gentrified, they no longer are what they were. We are really part of the architecture, our narratives are all inter-woven. That’s very specific to New York and that’s why I love it.

And you’re based in Mott Haven now in the Bronx?

Yes, I’ve been living in the Bronx since 2005.

What about that borough or that neighborhood inspires you?

I live on 140th Street, which is one of the main streets in Mott Haven. Being there allows me to access many things that I wouldn’t have if I lived somewhere else, like the lady that sells the tamales on the weekends who’s always there but if I don’t get there by nine, they’re gone. It’s just the proximity to things that I feel are a part of what makes me happy. And the people. It’s a mix of African American, Latino, Caribbean…but it’s changing. It’s changing a lot.

Tell me a bit about the art exhibition projects that you do.

I was accepted to be a part of a program called Artists in the Marketplace through the Bronx Museum in 2007. It teaches emerging artists how to navigate the art world and gallery system. I remember the first day one of the speakers called us all ‘nobodies.’ I was taken aback because the program was very competitive to get into, but it made me reconsider how I thought about my practice up to that point. We’re always waiting for things to happen in this world, but we have the resources to do things ourselves. So I opened my bedroom in 2008 and created the Bronx Blue Bedroom Project and I ran that space for two years. It started with installation art but eventually I opened it up to 2D work as well. I would host art exhibits and invite people to have workshops and conversations. Then I decided to move to Athens with my husband in 2010. And at that time, Greece was in an economic crisis and it was falling apart. I tell my friends, when I arrived in San Francisco, everything had already happened, all the hippie movement, that was in the ‘60s and ‘70s, I was not part of that—when I arrived in New York, same thing. But when I arrived in Athens, I arrived in all of the madness. It was a really good experience, but a very difficult one.

When I returned to New York three years ago, I felt like I needed to have my bedroom to myself, so I decided to open up my living room instead and display only 2D work. That project was called AAA3A, my address, Alexander Avenue Apartment 3A. It’s the same dynamic that the Bronx Blue Bedroom Project had, it’s nurtured by the idea of sharing and being in an artist-run space. It’s also funded by the Bronx Arts Council so that’s how I’m able to sustain the project. I have eight shows a year and feature mostly Bronx-based artists.

One of the main themes of the “Hand & I” exhibit is feminism. How do you define feminism and how is it presented in your work?

I think there are a lot of disparities between the sexes, not only between men and women, just in general. The more we continue to address those disparities and talk about them and really voice them, maybe things will begin to change. So that’s how I see feminism, the fact that I keep doing my work and I’m not stopping.

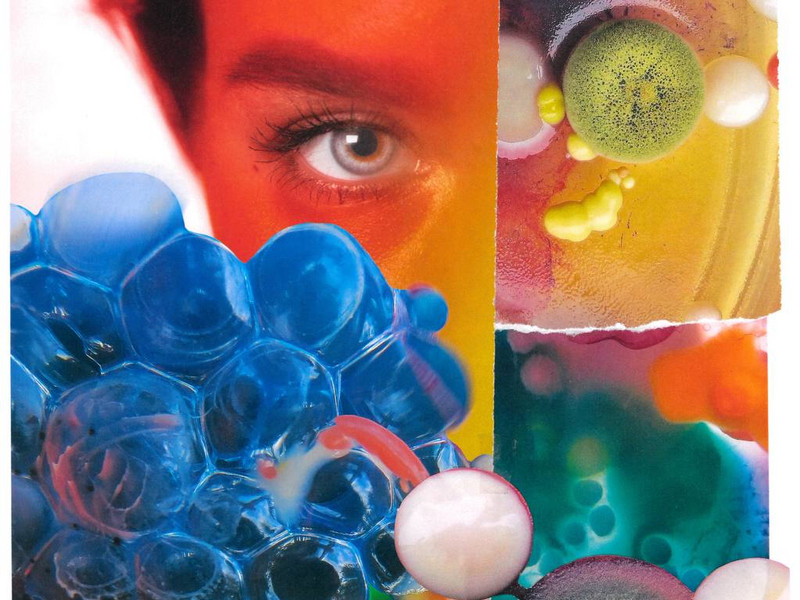

Going back to comic books, through your work, are you reclaiming the depiction of women in comic books?

Yeah, absolutely. I did a series based on women that I find in comic books because I wanted to appropriate and take the imagery of the women back and empower them with my hand and my composition. Sometimes the women are not exclusively in positions of power and I feel like they’re just seen as sexual objects. But when they’re removed from the male gaze and they’re embroidered they have a very different feeling. They’re sexual, they’re erotic, but they’re them. And there’s a lot of strength and honor in that.

That’s interesting because there’s more push now to diversify the comic book space.

Earlier this year the Brooklyn Academy of Music hosted a black comic book expo. Absolutely, there has to be. I think we’re really living in interesting times, there’s an awareness of the fact that the same narrative has been repeated for so long and now it needs to be changed.

What do you think is the root of the push for change now?

Trump. I think we need to create an awareness of each other and what has happened in this country. We need to name things as they are because I don’t think we do that. We’re starting to talk about things but they’re still not being fully addressed.There’s a lot of forgiveness that we all have to give to each other. For many things.

Who are some other artists and what are some other visual arts that inspire you?

I’m very inspired by all of the folk artists. But one artist that is sticking out to me right now is Fred Sandback. He's a white artist who worked with string. I think about him a lot because my work always has a lot of moving parts. Whenever he had to install anything anywhere, he would just show up with a shoebox of yarn. His work is extremely minimal but he creates space with it. The illusion that’s created from the simple gesture of creating those lines is a force.