Office – How did your collaboration first come about?

Asger Carlsen – Originally VICE called me up to talk about what I wanted to do for their photo issue, and I suggested collaborations could be fun. I especially wanted to do one with Roger. Ever since I saw his books, I was very fascinated by his work, and I always felt like if one day I could achieve something that had that quality, or that sort of universe… Anyway, VICE introduced us, and it was a good experience. We produced something like six or seven images for that issue, and we had a good response, so we had a couple offers from publishers and we agreed to continue the project and make it into a book, and feature the work in a few shows as well, around the world.

O – Were you already familiar with each other’s work? How did you know your styles would be a good match for one another?

Roger Ballen – Yes, a bit. I live in Johannesburg and Asger lives in New York, and I’m not familiar with everybody’s work out there since I live so far away. But I had seen his work, and it was very different than a lot of the photography I’d seen, it had an edge to it, it was surreal. It had strange, mysterious, enigmatic aspects to it that I identify with. I found it interesting and provocative.

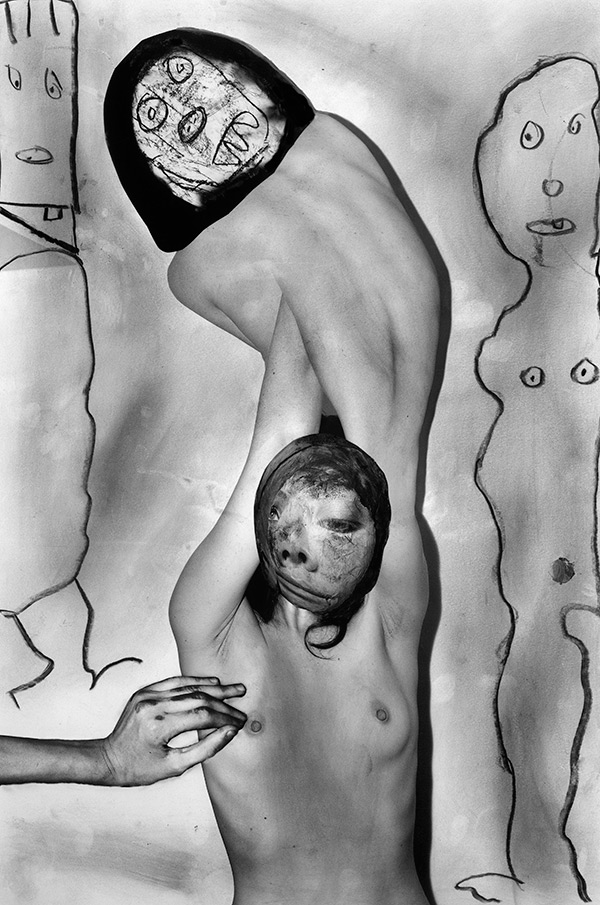

AC – I think we have a mutual interest in certain things, we both deal with work that comes from a subconscious level. We’re not trying to make images that depict the real world, our subjects come from an inner place. We make images that come from our own minds, you know?

O – Your work as individuals is often described as disturbing and dark. What is it that inspires those thoughts and feelings in people?

AC – I understand that people can feel uncomfortable looking at my images. I think for me it comes from a feeling of not fitting in. I mean, I was a commercial photographer before this, and I always had this feeling that I didn’t belong. I don’t really think about my work as having a dark element while I’m making it, but sometimes afterwards I do think that maybe I went too far. But the investigative process, getting somewhere else than what I’d originally trained myself to do with photography, it’s always been more important. So it might make others feel uneasy, but the fact that you can create that feeling with something so simple as photography, I think it’s an amazing thing. I think we both have an interest in the complex and the strange, that sort of thing. Roger has said “I am an alien,” and I can relate to that feeling. It’s always been like that, before I did photography, I had to find my own way of expressing myself.

RB – I’ve been at this fifty years, and it’s very clear to me that people are out of touch with their own interiors, their own personality, their own identity, so the pictures scare them, because they’re not able to integrate one part of themselves with another part of themselves. If they think the work is dark and disturbing, I don’t know what they feel about life itself. It isn’t a ride on Santa’s snowmobile. [Laughs]

O – [Laughs] So do you feel that you are visualizing things that people don’t typically have to confront?

RB – Well they confront it, they just repress it. They come across it but they don’t let it integrate with themselves, or they’re not curious about it. So they look at it and do their best to swallow it so they don’t see it again. I’ll state without any hesitation that what we refer to as repression is the biggest problem in the world today, it comes out as anger, aggression, hostility. All the negative things that come out of humanity are a result of people’s inability to be in touch with themselves. It’s probably a social thing, because the biggest fear that everyone faces is their own obliteration, and Western societies don’t deal with it well, they just supplant it with mass consumerism. The pleasure principle is not being in touch with oneself, it comes from consumerism, which is the evasion of the human condition, I guess. If you think what I’m saying is garbage just turn on the TV set in New York and go through the two hundred channels and see what’s there. See who makes money in society.