"Karoshi": From Cubicle to Grave

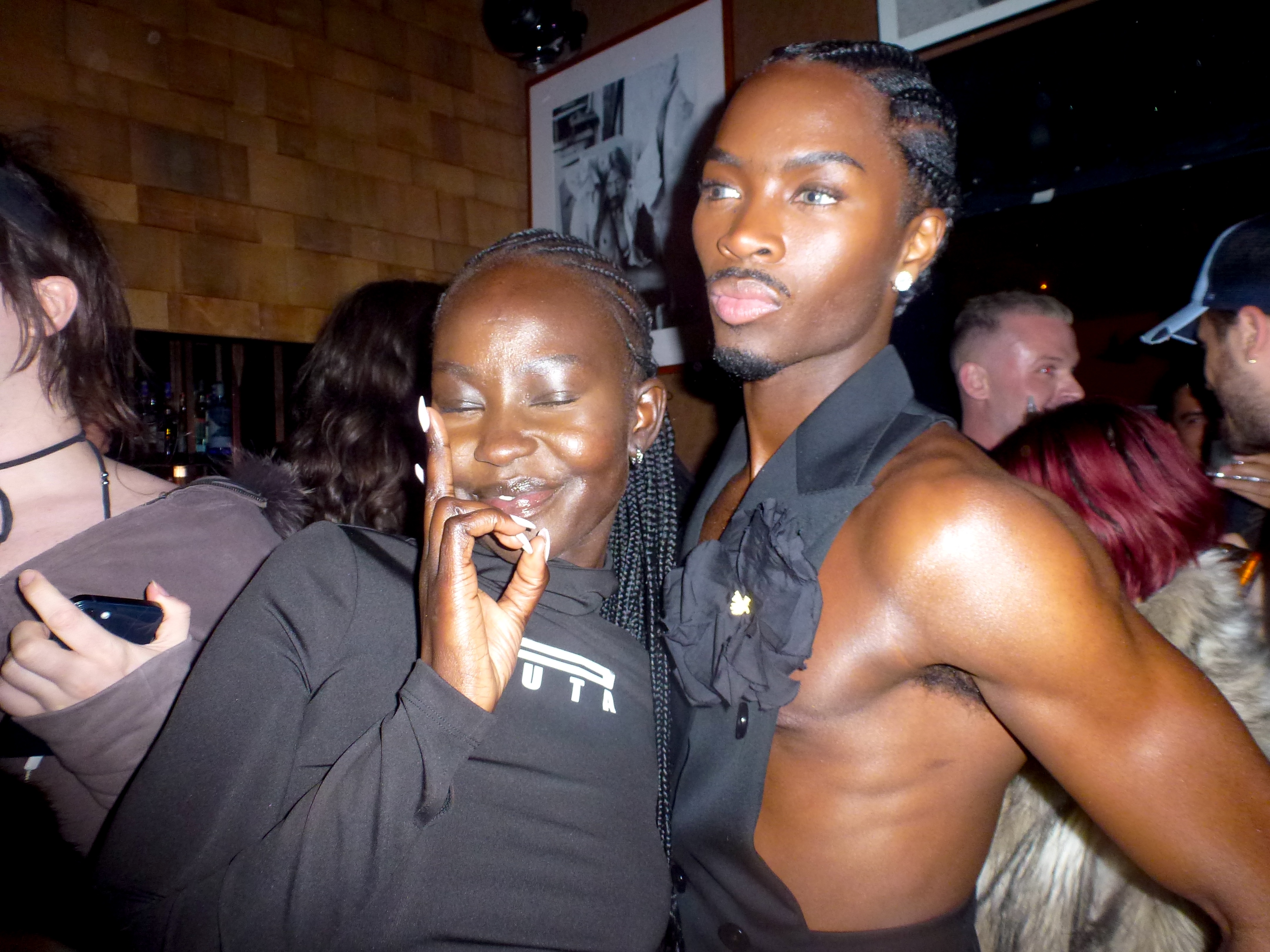

“Self-taught and constantly learning,” Furukawa brings an experimental spin to her heritage of Swordsmiths and Kannushi. She started making jewelry out of found objects and has since taken up silversmithing in the past year. Born in California, Furukawa grew up traveling between Japan and the US — two countries infamous for their ass-kicking and sometimes deadly work culture. And, having been in NYC for 6 years, Furukawa is no stranger to the chaos of work life and the exhaustion that follows. Furukawa pulled inspiration from Instagram archive @ShibuyaMeltdown, which posts pictures documenting karoshi. As the account's popularity grew, the West has also found themselves in a position of solidarity and understanding with the fellow overworked salarymen of Japan.

office asked Furukawa some questions about her creative process, her inspirations, and her thoughts on the Shibuya Meltdown phenomenon. Read the interview below.

office— What made you want to use the visuals of “death by overwork” to advertise your own products?

Juriel Furukawa— I officially entered the corporate world as a designer a couple of years ago, and while I'm grateful for the opportunity, it marked a significant shift in my identity. Having always operated as an independent designer/artist, I felt the need to conform and shed aspects of myself, it seemed like I didn't naturally fit into that structured setting.

Being fully immersed in the workforce forced me to reassess my life desires, goals, and personal identity. I faced the reality that despite promises of a better work-life balance, the unstable economy has let down the younger generation's pursuit of stability and a promising future through the traditional path of college and employment.

The once-assured path to a comfortable life no longer guarantees homeownership, the ability to support a family, or a leisurely retirement. Following the conventional lifestyle appears to trap individuals in an endless cycle of work, perpetuating a relentless rat race.

The concept of "death by overwork" in my visuals serves as a metaphorical expression, drawing from my experiences growing up between Japan and the US, and entering the corporate workforce. In this context, jewelry making becomes my glimmer of hope and personal joy.

As an artist, do you experience that same type of exhaustion that you reference in your shoot? Or, do you experience something different?

In some ways, being able to work in a field related to my passion is a blessing, but it comes with its challenges. It can be somewhat soul-sucking if you struggle to differentiate between work and personal purpose. I make a conscious effort to disconnect and avoid becoming too attached to what I create, which helps. However, it can also lead to a sense of meaninglessness, and that's where I need to strike a balance. I've learned to find meaning through different avenues such as personal work vs work, relationships, and hobbies, which I believe is a much healthier way of approaching things.

The concept of “dream jobs” is something that’s really come under fire these past few years, with a lot of people responding with something along the lines of, “I don’t dream of labor.” As an artist, do you feel as if you’re commodifying your passion to live?

I’m sure that some people do find their “dream job.” Personally I feel that having a life out of work that fuels you is vital. Finding value or identity through your job alone is destructive, because that’s when you really commodify yourself. You need to know your value outside of that space.

I view things that I make in work separate from the work that I make for myself. It’s healthy to have that separation so you know what is yours. It’s important to have something that is just for you that brings you personal fulfillment.

How do you separate your purpose from your capacity to contribute to the economy?

At this time in my life, it’s more important for me to think about how I can contribute to society through my own sense of purpose and immediate relationships. Once I'm clear on what that is and I can comfortably suffice on my own, I can shift focus to how I can contribute to society on a larger scale. I’ve always felt a strong desire to be in arts education which is where I see myself in my late future.

@ShibuyaMeltdown has garnered a status as a sort of notorious archive. Some people find it funny, some people find it artistic. I’ve seen them use pictures of people at their lowest to sell merch. Do you think there’s something dangerous about the way that the @ShibuyaMeltdown account operates?

The @Shibuyameltdown account raises concerns about privacy. While people may find enjoyment or fascination with the phenomena, exposing individuals' faces without consent is a bit concerning; the potential backlash it could have on their professional lives, especially considering Japan's rigid work structure. Although it's intriguing for outsiders to view these images, it does feel somewhat invasive to turn it into a spectacle.

You pull from a lot of @ShibuyaMeltdown photos that showcase a combination of overwork and drunkenness. Because both the US and Japan have notably unbearable working conditions, do you think that has something to do with why we’re always getting so drunk?

The new generation is deeply affected by the struggling economy, contributing to the "I do not dream of labor" attitude. The lack of employer loyalty, evident in widespread layoffs, has forced employees to adopt a new mindset toward work. Some turn to alcohol as a coping mechanism for unfulfilling work and a sense of purposelessness. I've managed to separate my work identity from my broader purpose, which helped me escape that negative cycle. Constantly proving oneself in the workforce, navigating office politics, and adhering to social norms can make one feel like a product. I've learned to appreciate soft skills, which I wouldn't have developed otherwise, and found purpose in building a life beyond work.

In the US, there are passed-out, drunken people all over the city who don’t get as much artistic attention as those in Japan. Why do you think that is?

The corporate Japanese work environment is full of extensive formalities and a demanding workload, creating an incomparable level of stress compared to the U.S. Strict social rules force individuals to conceal their true thoughts and emotions while displaying high respect for their superiors. Social hierarchy is crucial, and bosses may exploit their positions, contributing to extreme burnout and exhaustion, often manifested in alcohol abuse.

Most people do not have a life outside of work and are not encouraged to. I think the artistic element arises from this stark contrast between conventional Japanese culture and these extreme situations, the urban landscape of Tokyo/Shinjuku, and the foreign perspective that allows us to view these phenomena as spectacles from the outside.

What’s interesting about the Japanese vs. American drinking culture is that, in Japan, most people realize that it’s perfectly safe to pass out in the street. Because of that, do you think there’s a heightened fascination with the “dirty” aspects of Japanese culture?

I think it is generally safe, at least for Japanese men to pass out on the streets. People are naturally drawn to contrast, and the more extreme it is, the more captivating. Japan, being a collectivist culture, highly values harmony and uniformity among its people. It’s beautiful in that it results in an overall shared attitude and respect; everything in Japan is clean, neat, and organized.

The disorganization and chaos apparent in the late-night streets of Shibuya reveals an extreme breakdown of that structured order which is why I believe foreigners find such a fascination with.