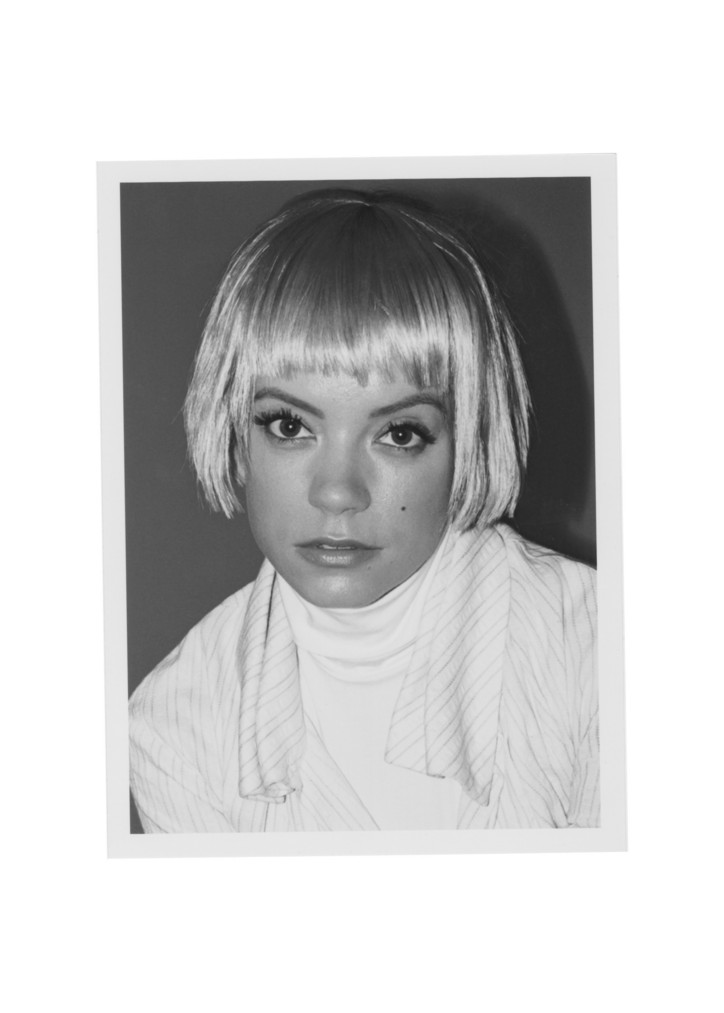

Lily Allen Looks In

“I got really lost on Sheezus,” she tells me. “As an artist, as a female, and as a person, I just had to re-evaluate a lot of stuff.” Her 2014 identity crisis was only amplified by the fact that she was suffering from postpartum depression when the project began. “For the first time, I consciously started letting other people make decisions for me… I didn’t really know who I was, so I was looking for other people to tell me, and then when it came to trying to sell that person, I was like, this is not me.”

Unfortunately she was already too deep to get out. For well over a decade, Lily has been known for her unabashedly critical worldview and penchant for irony. In fact, it’s what has drawn many to her in the first place. But the second a middle man comes in and tries to commodify her candor—essentially priming listeners with an “Explicit Content” warning before consumption—is when things tend to reach a boiling point. And they did.

Lily was being sucked into Twitter feuds. There were articles being published shaming Allen’s “crooked” views on feminism, and she was even forced to apologize for cultural appropriation in her videos, accused of using the black female body as a prop. She tells me that after this album, she fully lost it, subsequently divorcing her husband and attempting to pick up the pieces from both her public fallout, as well as the one taking place in her psyche.

The same public that lauded her bluntness and “tabloid queen” persona was suddenly turning on her. I tell Lily that when she (as well as many other female British artists like M.I.A, Amy Winehouse, and Duffy) gained popularity in the mid-to-late 2000’s, it represented a new kind of female badassery, one which she thinks doesn't even exists anymore. “I feel like we were all very unashamedly ourselves and honest, and I feel like at that time, people were ready for that,” she tells me of her “no fucks given” debut. “Then maybe people got scared and became more conservative again, but I think that has more to do with social media than anything else.” Considering her tumultuous relationship with Twitter and the role this played in her downfall following Sheezus, it’s ironic—fitting, even—that four years later her follow-up record is titled No Shame.

“I wanted to stay true to my creative self and still be able to deliver candid, honest lyrics with a punch, but I think people were sick of hearing me berating the world and lovers or whatever,” she says, describing the shift in perspective and priority going into this new era. “I wanted to keep that continuity in my writing—being me and observational—but I think it had to become introspective rather than extrospective.” Whereas her process was previously characterized by satisfying her record label’s expectations, this time around she built her own studio space in London and let her ideas simmer—not only that, but she also executive produced the whole record.

The new music feels like Lily Allen 2.0—refined, matured, and streamlined. It’s lo-fi and bass heavy, adapting to current music trends without losing her distinct voice amongst them. But a true recognition of this sonic shift is incomplete without listening beyond the bass and really hearing what it is she has to say. On chills-inducing standout track “Apples,” she goes through the intricacies of her divorce over spacious and minimal guitar plucking, ultimately comparing it to her parents' broken relationship: “Four years in, you’d given me my beautiful babies / but it was all too much for me, now I’m exactly where I didn’t want to be / I’m just like my mommy and daddy / I guess the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree.” On lead single “Trigger Bang,” she reflects on the evolution of her relationship with partying, one that now comes from a place of difficult lessons learned: “You’ve got bad bones / I’ve got bigger plans / Gonna put myself in your hands.”

The “hands” she is referring to, she explained in a tweet, are meant to be those of her listeners. Allen is more vulnerable than ever on this new record, allowing her to embrace her fans in a way that may have previously been clouded by her love for calling out everything wrong in the world. And the love is mutual—at Music Hall of Williamsburg, she stands on stage stoic and self-deprecating as ever, but with a subtle smirk that seemingly thanks her screaming fans for sticking with her through thick and thin. She’s open about her struggles post-Sheezus, presenting each new song in the context of her personal breakthrough. It emphasizes how the complexity of Allen’s candor is best understood face-to-face.

“So much of human interaction when we’re talking is that we understand people based on their body language and tone of voice,” she tells me as our conversation shifts towards relationships in the age of social media. “You could read one sentence on Twitter or a caption on Instagram, and you would read into those words something completely different than what I would read into those words.” She tells me that she has lost many friends because of this disconnect between real and digital. “For many of my friends, the reason we don’t talk anymore is that they know I’ll call them out on their bullshit they post online. They can’t face that confrontation.”

The core of what Lily Allen does, and what has helped her achieve such sustained relevance stems from her ability to observe human interaction, filtering it through her whimsical wit, ultimately producing a brutally direct pop product. Before performing her classic “Fuck You,” she prefaces: “I wrote this song when George W. Bush was president, but now I guess it can be re-dedicated to a certain someone in office.” The crowd cheers in this revelation.

We will always be pessimists. We will always need to express our outrage and discontent toward something with a bursting, “Fuck you!” And in an age where internet warriors are relentless in trying to tear down idiosyncrasy—to shame you into being tame—it’s a blessing that Lily Allen still finds a way to come out on top.

When I ask Lily if her songwriting process has changed at all throughout the years, she thinks for a quick second before responding with characteristic nonchalance: “I’ve always been just making it up as I go along—there has never really been a method.” Thank God.

No Shame is out June 8.