LVMH Prize Finalist - Kozaburo

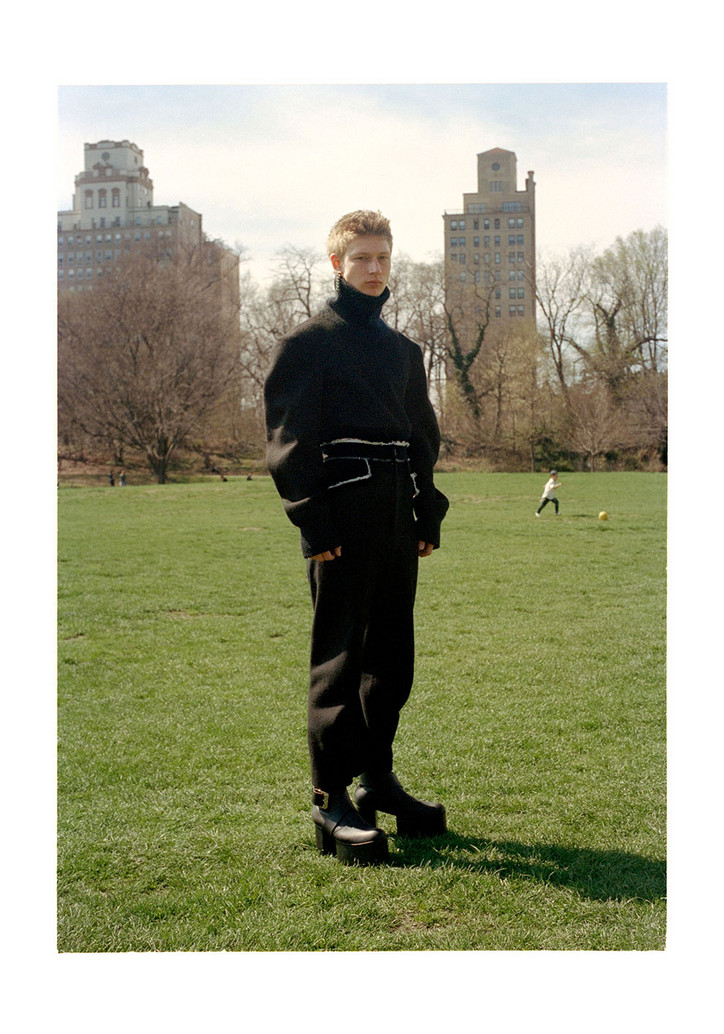

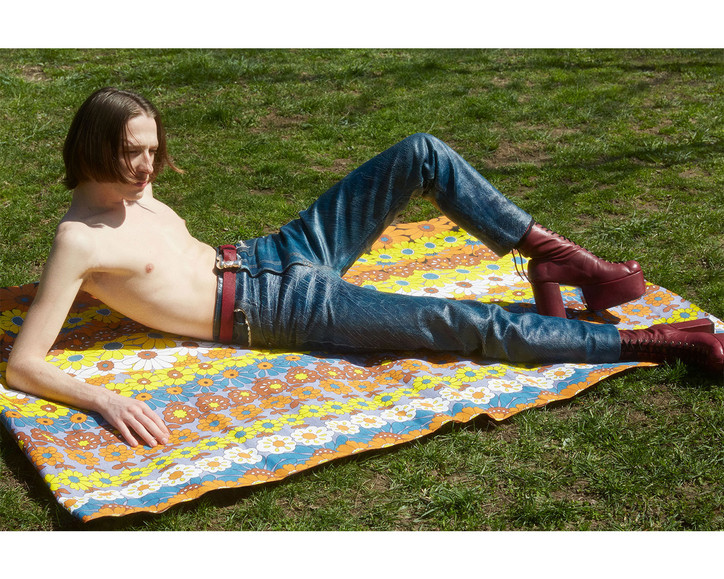

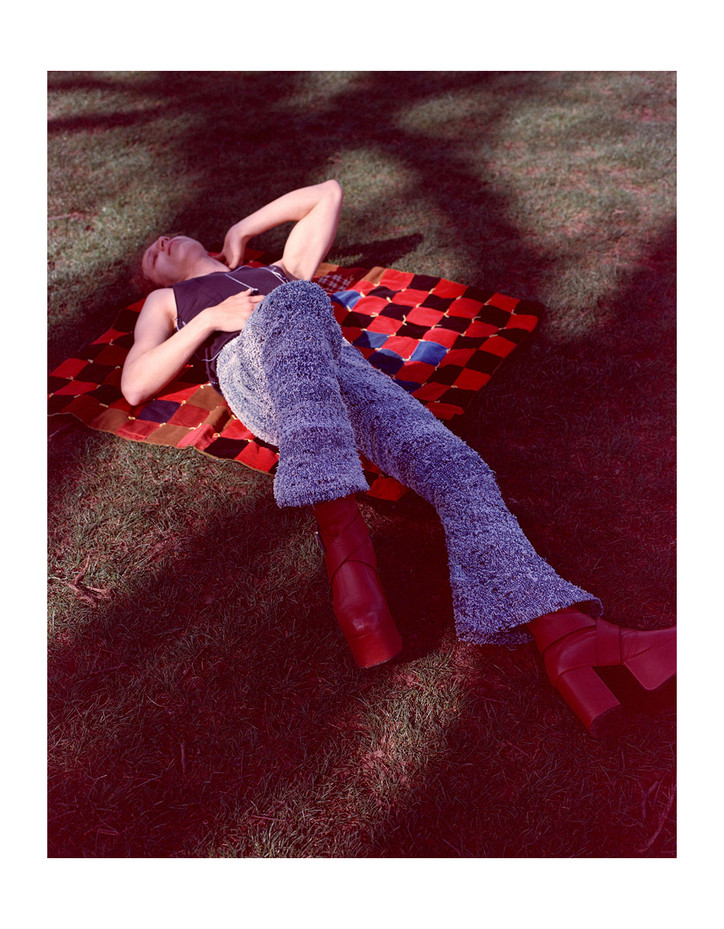

Raised in ‘90s Tokyo and trained in London and New York, where he is currently based, Kozaburo Akasaka has gained fast and growing attention for his namesake line of men’s garments, which offset entropic cuts and inventive material treatments with intricate tailoring and a deceptively precise finish. Drawing heavily on the music and streetwear he discovered in adolescence, Kozaburo’s designs are a tangle of narratives, each piece a story composite, yet personal.

Focused even amidst the excitement of his nomination, Kozaburo spoke to us from back in Tokyo, where he was busy overseeing production of his new collection, to be premiered in Paris and New York later this year.

What were you doing when you heard you’d been selected as a finalist?

I was having brunch with my wife, actually. I was very happy when I got the call, of course, but I also was very moved. There’s a lot of difficulty that comes with being an emerging designer in a new country—not just building your brand, but simply living in the US as a foreigner. My wife and family have been very supportive throughout my career, so it’s a nice validation to have this happen after so much effort.

As part of the nomination process, you’ve had to explain your work to panels of experts. Was this an intimidating prospect, given the stakes?

It’s definitely good practice, as this is a commercial necessity for any designer—and of course, my techniques are often complicated, so it was an interesting challenge to explain things in only a sentence or two. It was also nice to see how these influential people responded to the work. But really, the reason I make garments is because I can’t express my vision in any other format. This is the medium I’ve chosen to tell my own story, so I feel that the visual presentation always comes first.

Your pieces are still generally made by hand, one at a time.

Yes. There are some helpers who assist me from time to time, but I typically work on my own, with my hands.

Is this your preferred approach, or has it been more of a practical necessity?

Both. I love the physical process of creating, it’s something I want to keep as central to my practice. But it also reflects my business, which—at least so far—is of a small structure and works with small orders. It’s made sense to do it all on my own. But as things progress and the workload increases, it’s something that will have to be addressed.

Given the intricacy of your techniques, I imagine it’d be as great a challenge teaching them to assistants as it’s been explaining them to panelists.

It wouldn’t be easy, but then, if I can do it, anybody can. [laughs] Because the methods are so hands-on, there would inevitably be slight differences in my results compared to others’—but I like that, because my work is really about celebrating the individual, embracing differences and recognizing the uniqueness of each character. So I think that process would be in keeping with my vision for the brand.

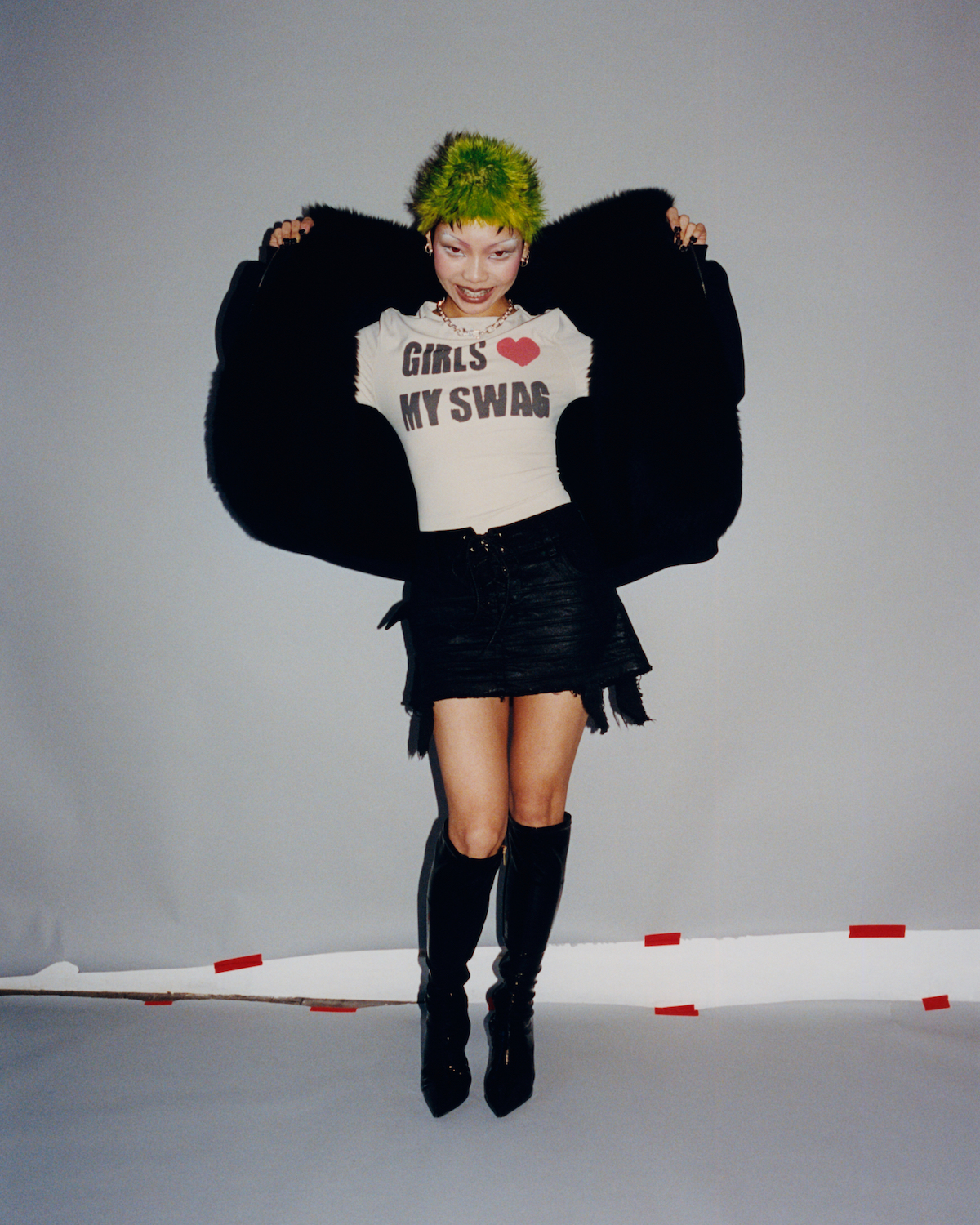

How has this emphasis on individuality translated into casting? Is there a prototypical Kozaburo model, or do your leanings change with each collection?

Generally, I like each model to be different—no specifics for skin color, hair length, or body type. I want to combine individual looks that together create a harmony. Seeing how they carry themselves, you just get a sense that some people fit, that they look great in the clothes and match the vibe of the brand. It’s really more about attitude.

Between Central Saint Martins and Parsons, you spent some time as an assistant at Thom Browne. What was that experience like? Have you retained any lessons from your time there?

For me, the biggest lesson was simple but crucial: You must be true to yourself. In that sense, Thom showed me by his example. As a designer, I really respect how he’s been able to extend his vision yet retain a signature style. Of course, we shared a certain dedication to technique, but more than anything, I was impressed by how he built his brand as an individual. By the time I became interested in his work, around 2007, he had been a guest designer for Milan Fashion Week, where he had a show of forty models wearing the same suit on the runway. To me, that was very punk. It wasn’t only about the clothing, it was about the statement being made. So that was the main impact he had on me—his attitude. I try to carry that same approach today in everything I do.

You’ve said elsewhere that “the timeless design of classic men’s apparel is at the core of [your] aesthetic.” I wonder which elements, material or otherwise, might lend themselves to “timelessness?” In your own designs, has this meant retaining specific cuts, proportions, palettes? Or is it something less tangible?

I think my vision is an honest one. I want my garments to be relevant over a timeline. I look at the past hundred years, imagine the next hundred, and then try to make clothes that I could see people wearing at any point along the way. Part of that is producing items that people have been wearing for a long time and will likely continue to wear: jackets, jeans, shirts. I’m not inventing any new garment categories, I’m just using classic formats and showing differences in the construction and detail. I want my clothes to feel somehow both vintage and current, and to take on new qualities over time as well.

What about your use of recycled materials? Given what you’ve said, one might read that practice as a literal means of extending a narrative—or then again, it could simply be a matter of aesthetic preference, even of finance.

When I’m creating a new collection, I might not know how much of a certain textile to buy, what to have fabricated. Oftentimes, recycled material has simply been more accessible and affordable. At the same time, I do like the notion of the material carrying a unique history, even before I use it. From the beginning, my clothes already have a little bit of age to them, a bit of character—and then, of course, as people wear them, they take on additional character as well. In Japanese, there’s a term called mottainai, which essentially means “waste nothing.” That’s part of how I was raised, “Finish your meal,” and so on. So the notion of “sustainability,” which is such a big word in fashion right now, is already quite natural to me. It’s about using what’s available, recognizing a “soul” in each item, and creating new narratives.

In creating your designs, are you generally inspired more by concept or craft? Do you sketch and then execute? Or do you discover new directions by manipulating materials?

I’ve never been one to make a hundred sketches of something—it’s more about letting the process happen. So let’s say I start with fabric manipulation, but then maybe I realize I’d like to use a certain seam, for which a more durable material may be better. So then I start thinking about what else I can do with that new material. How can I shape it? Is it better as outerwear? From there, the initial idea can change quickly and repeatedly. So really it’s a fluid process, where everything’s developing at once.

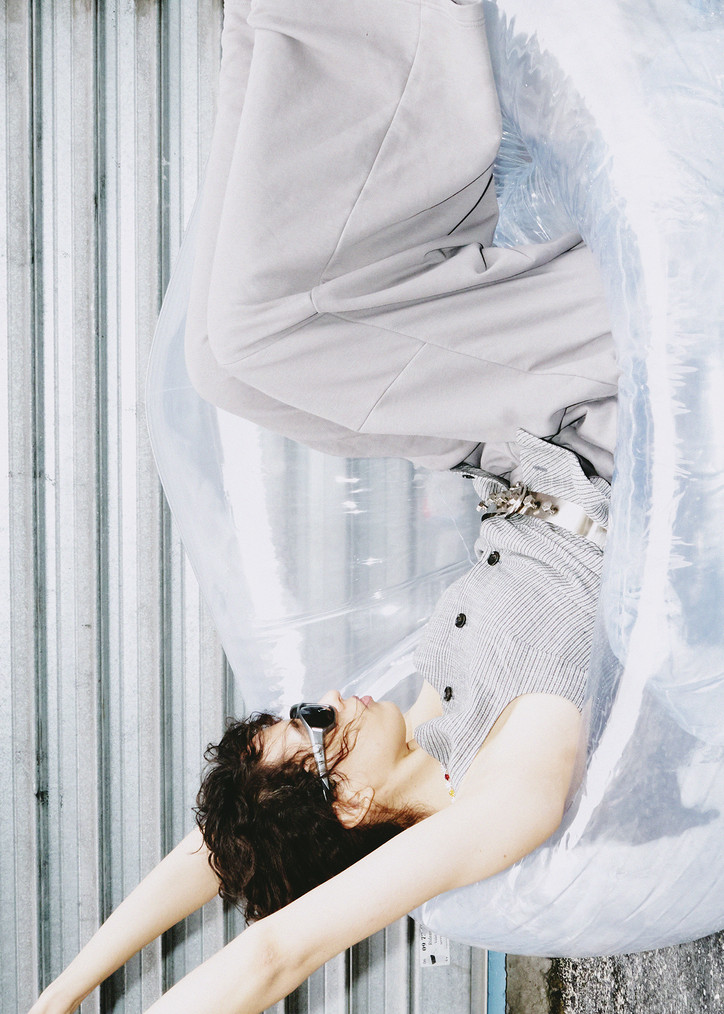

Your runway and lookbook presentations have been increasingly collaborative efforts, reflecting the input of stylists, photographers, set designers and musicians. How have these “outside” elements changed the way you saw your own garments?

It’s just a different perspective. Collaborating with outside talents has brought a new way of understanding the work, which I’ve quite enjoyed. Their worlds are quite different from mine—and, as a result, they often see something different in my work than I do. So it’s been quite interesting, incorporating their vision into my own. The result becomes something new, and I’m learning to enjoy that process.

Looking ahead to June, how are you preparing for the final jury presentation? Are you rehearsing your speech, going through practice runs with models?

To be honest, I’m not preparing any specific presentation or speech, because I feel like this whole process has been my preparation. As honored as I am by this opportunity, I still have to continue building my brand. I’m very busy now creating my new collection, doing samples, working on production, talking to the showroom and working on PR. In a way, I feel that doing this work is the best practice I can do.

If you win the Prize, how might you use the money? Are there specific goals it would help you achieve?

The first thing would be to organize a big supper and invite all of my friends and collaborators, almost like a “thank you.” After that, I’d simply invest in my brand. As more stores begin carrying your work, you start thinking ahead towards production and realize how much money is involved. This will always be true, of course, but the Prize would be extremely helpful in taking the next steps.

What kind of insight or guidance would you hope to gain from the mentorships?

I’m not sure yet! LVMH is such a big company with so many experienced people, and I’m sure all of their stories would be useful. I think I could learn a lot of valuable things about business and branding, allocation of budgets. The nice thing about this experience is that it forced me to really look at what I’m doing and how I can get to where I want to go. I’m pushing as much as I can, but I’m still trying to keep it all centered, keep my vision clear and find new opportunities. My priority is my vision, being true to myself while moving ahead. That’s my mindset at the moment.

Read our conversation with fellow LVMH Prize Finalist Molly Goddard.