Mario Says Relax

So tell me about the show.

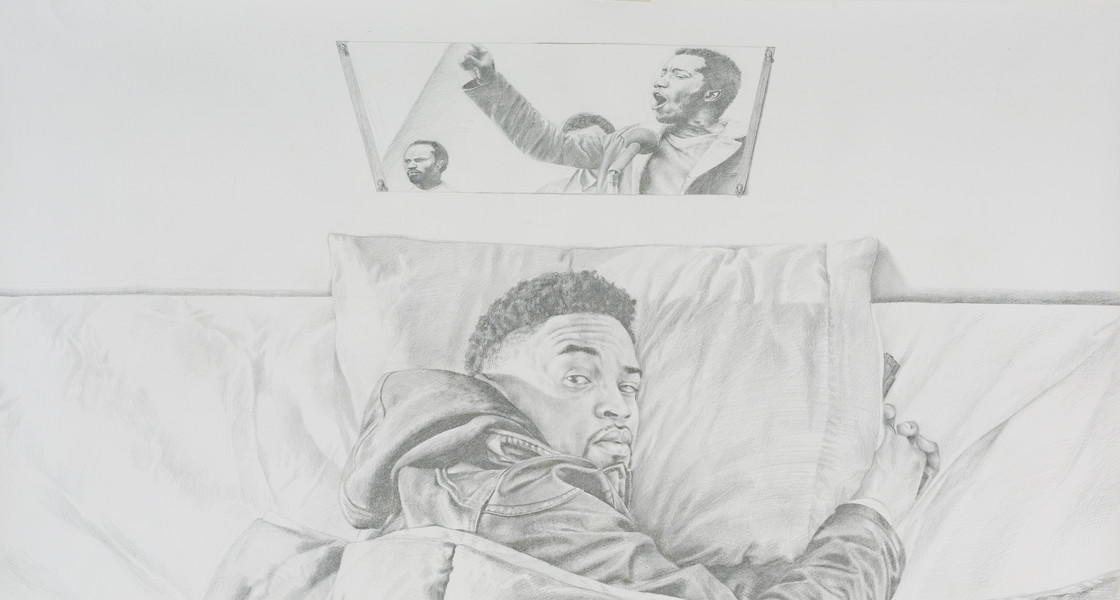

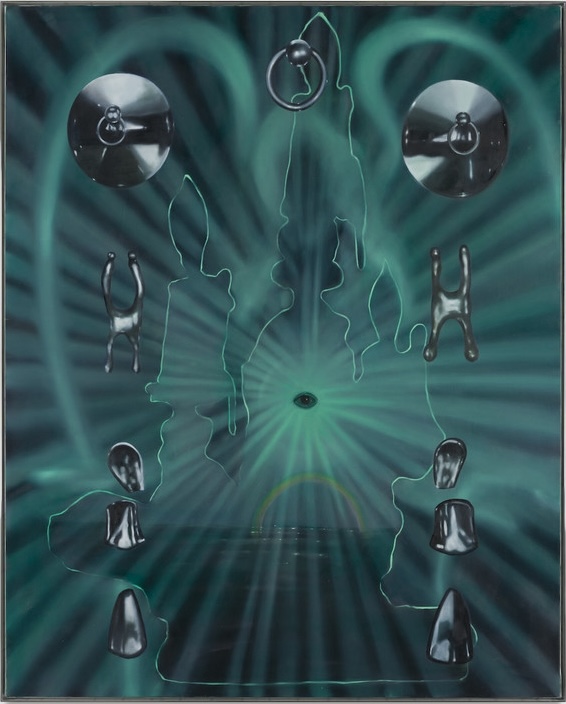

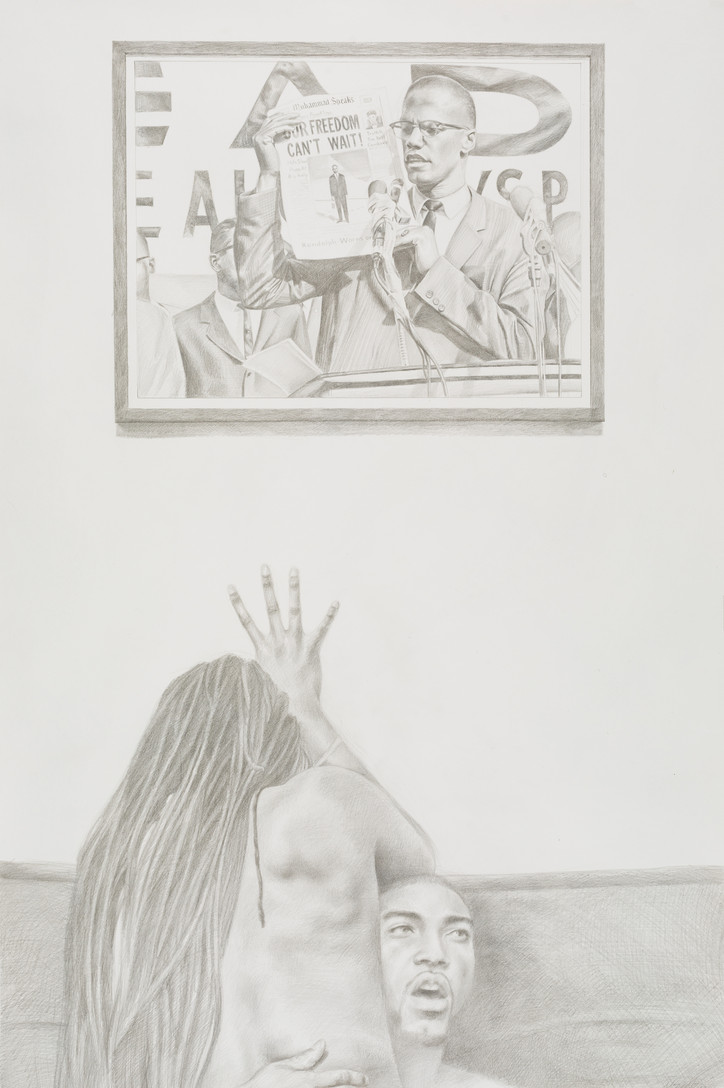

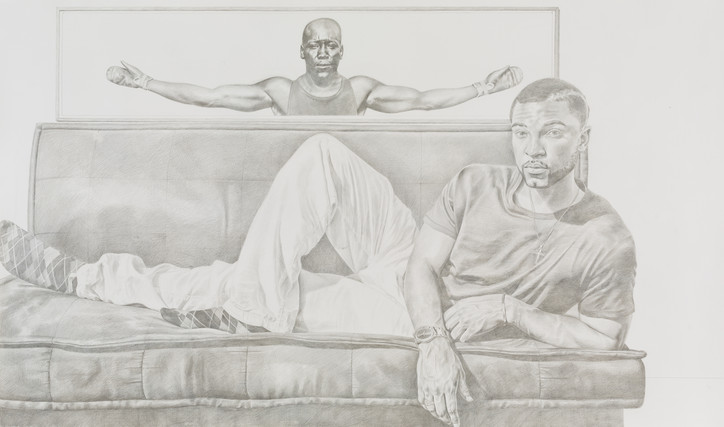

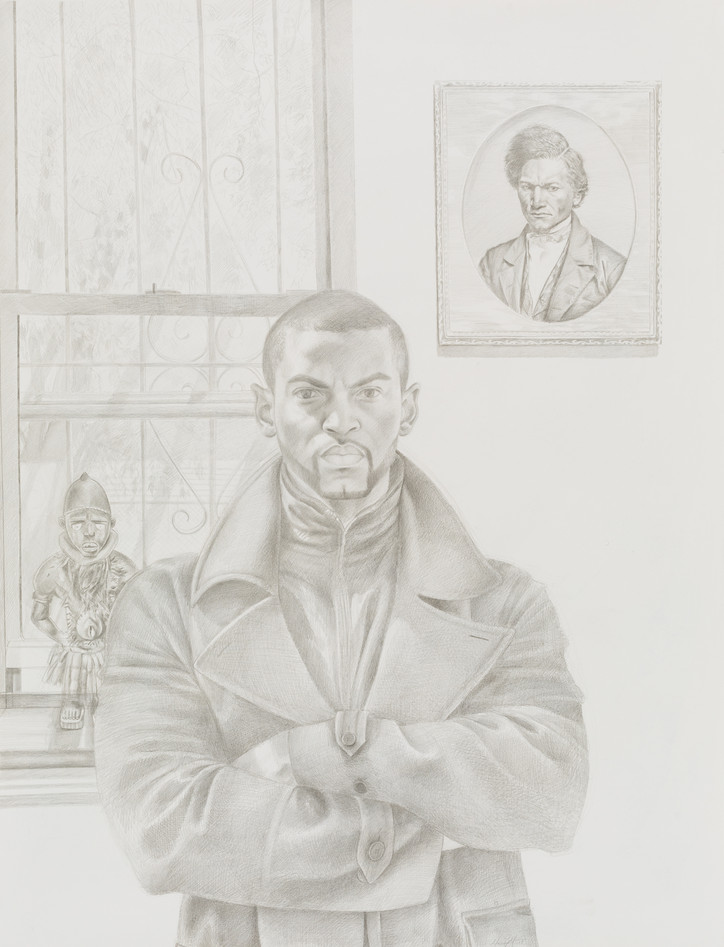

I guess the majority of the work in the show started around the idea of what it means for black men to relax, to rest. I started by doing these silver point drawings, so the idea came from me thinking about myself — before I was doing a lot of paintings of black women, thinking about black women in power and how to bring their images to the forefront of art and painting, but I got into trying to work on myself more, so I wanted to work on black men in America. I was thinking about the police killings and all the stuff that’s been happening and I began to think of it as a triple portrait — of me, an image of Frederick Douglass to the left, and then an N'kisi figure to right of me wearing a jacket. I just wondered, is it possible to show a black man relaxing? but at the same time make it powerful?

So that’s how it started. So then I had a seizure, then brain surgery — it was a lot. I had to recover from the brain surgery — I had the surgery in August of 2017, it hasn’t even been a year yet. But after that brain surgery, it made me think, well, in the moment when we’re forced to recover, I just started to think about what does it really mean for black men to rest, what does that look like? So I started thinking about historical figures like Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, and Googling images with searches like, “historical black men sleeping” or “historical black men resting,” and it was extremely hard to find. But in their moments of revolution and at the podium and all that, they had time to spend with their families, to take vacations, so me being forced into a state of I can’t do anything, forced to spend time recovering, made me think about, in America, especially for black men and black women, of like constantly having to work work work work work work — and not really having the time to think about self-reflection or care for oneself or even taking the time for oneself. So that’s where the work for the show is coming from.

I once heard on a radio show the question posed during a survey was, “What is your number one guilty pleasure?” and the number one response from Americans was “sleep,” which is just patently absurd since we need to sleep in order to live, so to feel guilty about sleeping is just insane to me — so I think maybe you’ve touched on something that’s true of American culture in general.

It’s definitely an American thing, I just think it’s more potent for African Americans. One, because you fall into certain stereotypes — if a black man is relaxing, or just chilling or whatever, then he’s seen as lazy, there’s this concept of laziness — what does that mean? For a lot of African American families, they don’t have a lot of wealth built up to, for example, take a long vacation. It’s definitely an American thing, even when an American goes to relax they’re constantly thinking about work, or bills, or when they’re going to get back and what they’re going to do work. For me specifically, I was thinking about these famous revolutionaries like W.E.B Dubois or James Baldwin and how they had to get out of the American psyche — James Baldwin moved to Paris, W.E.B. Dubois moved to Ghana, Malcolm X went to Mecca, and I think he spent the most amount of time in his life relaxing when he went to Ghana. Muhammad Ali had his belt taken away so he was forced to relax, and then there’s this machismo thing, this macho perception of black men — if you Google Martin Luther King or Malcolm X, they’re going to be very powerful images, but it’s extremely hard to find them just relaxing with their family. So I’m trying to get to what that looks like and how that’s perceived, and combining it with my personal experience. But yeah, it’s definitely an American thing — like in Italy, their coffee breaks are two hours, you know what I mean?

Do you feel different after the brain surgery?

I look at things differently, I don’t know if I necessarily feel different. Everything just happened so fast. I’ve never had a seizure before — that happened in July, and then I had the surgery in August. And they found a tumor in my left central lobe, that’s your language center, so they had to do a very specific type of operation. After that, I just wasn’t sure what was going to happen — am I going to be able to make art anymore? I had a lot of questions. Of course something as traumatic as that is going to change you in some respects, but I feel the same. But it made me think of traumatic moments, from a situation like getting arrested and beat up by the police, or a situation of having a traumatic moment of having a brain surgery, or just looking at constant videos of black men or black boys or black girls dying by police officers — what effect does that have on the mentality of a people and how do you take a break from that? What is rest from that look like? Is it even possible to take a break from that?

There’s an element of force that you keep touching on — being forced to rest. It’s kind of like a prison cell where they’re being forced to just be on this bed. Did you think of that? Would you be happy with that correlation?

I didn’t initially think of that, but it’s just a part of American history so it’s implicated especially when you’re talking about black men. I was talking to this artist, I was in this show in Charlotte, and he was wrongly accused and imprisoned for two years, and then he was exonerated and released so he makes work about that — and we talked about the similarities of being forced into a situation, of him not having control over his body, similar to me in far as having a tumor and surgery, it’s something traumatic happening to you and it’s not having control, for me it was different but for him he saw similarities.

There’s a couple pieces in the show that deal with Jack Johnson, who was the first heavyweight boxing champion who was black, and basically the way that they took his title away was by arresting him, by basically manipulating the law to take the belt away. This was in the 1915, and they just didn’t like him being the champion, so they literally forced this belt away from him, similar to Muhammad Ali saying he didn’t want to go to Vietnam so they took the belt away from him, forced him into a certain position. It has to do with force, but also with your own intuition, your own options, it’s both of those things. The difference is James Baldwin choosing to move to Paris, or Muhammad Ali being forced to have his heavyweight title taken away.

Where do you see black culture and the black experience in the United States today — where is it at? Do you feel like it’s better? Has it been incorporated into the overall culture, or is that even a goal?

I don’t necessarily think that’s a goal — I know my personal goal as a black man in the United States is just to be seen as human.

What do you feel white culture sees you as?

I think they see me as a lot of different things. I think that depends on who you’re talking about, depends on if we’re talking about police officers or white suburbia or specific communities, I might be seen as dangerous, for other people I might be seen as invisible. I think it depends. I hear this a lot, ‘Are we at a turning moment? Have we seen progress as far as blacks in America?’ I think there has been, but also I am critical of that because I think what happens a lot of times in history, like in the Civil Rights Movement and before, people like to say, ‘Oh, it’s not as bad as that,’ but when we actually look at how history is set up, like in the 60s, if we talk about the Civil Rights Movement, a lot of what Martin Luther King did, the structure of that system was making things available to photograph, he organized those marches so that the outrageousness of people getting beaten was seen on camera. The same thing is happening now. I firmly believe that 30 years from now or so, kids are going to say, ‘Oh my gosh, you lived in that time when police were shooting all these kids and things, what was it like?’ and not everyone is going to be able to say, ‘oh I was marching,’ no some people were sitting on their couch, or reading a book, some people don’t see it at all except for on their tv — I think what happens is very cyclical, which is horrible — it’s like, when are we going to get to a point when we really move forward?

"Recovery" will be on view at David Klein Gallery through August 11, 2018, in Detroit.