Mr. Sandman

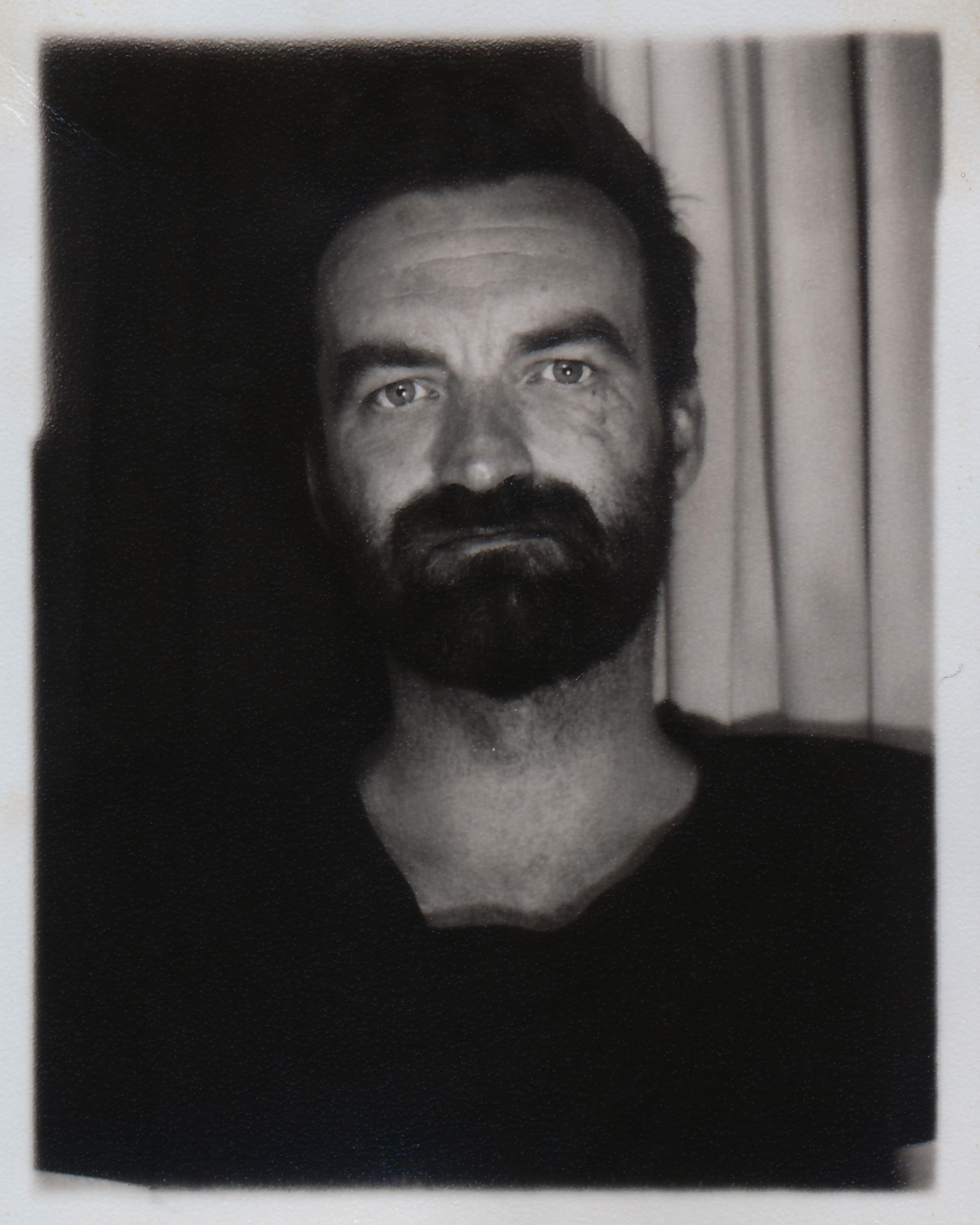

Tell me about the show.

The show is about destruction and process. Actually, I just saw your article about Umber Majeed talking about creation and destruction—it’s funny because I know her, as well. She’s a really good friend of mine. So, the show revolves around destruction and process basically. I grew up in Istanbul, but I always visited New York and always had a connection with it and American culture. But being here, there’s very real destruction happening—terrorism attacks, and other things that are related to that, versus watching American TV, like watching a lion eating a gazelle on the Discovery Channel, or skateboard wipeouts on YouTube and stuff like that for the purpose of entertainment—the juxtaposition of that is one of the reasons that I got into destruction. I was always enticed by that when I was a kid. Also, the sheer physicality of destruction is really important to me—how things can be really out of control, and what is control? What is an accident? These were the starting point for me—what destruction is and the future of what it could be.

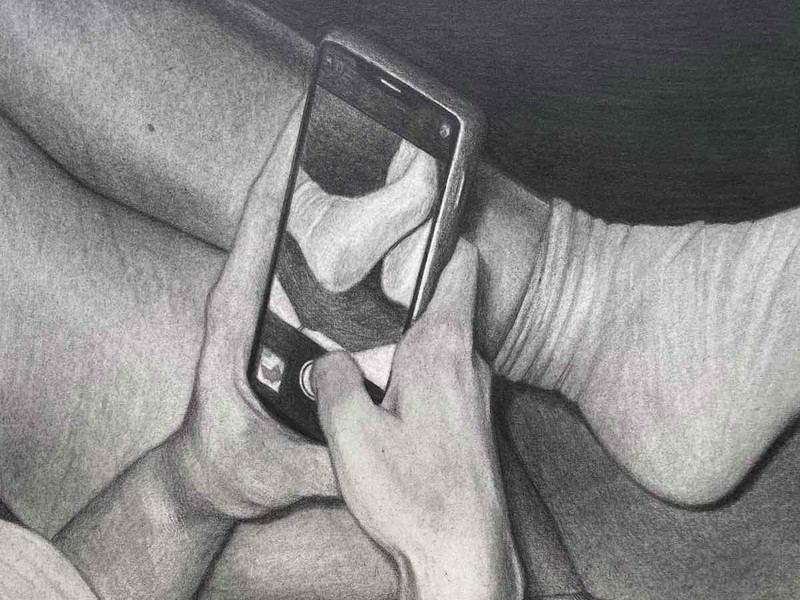

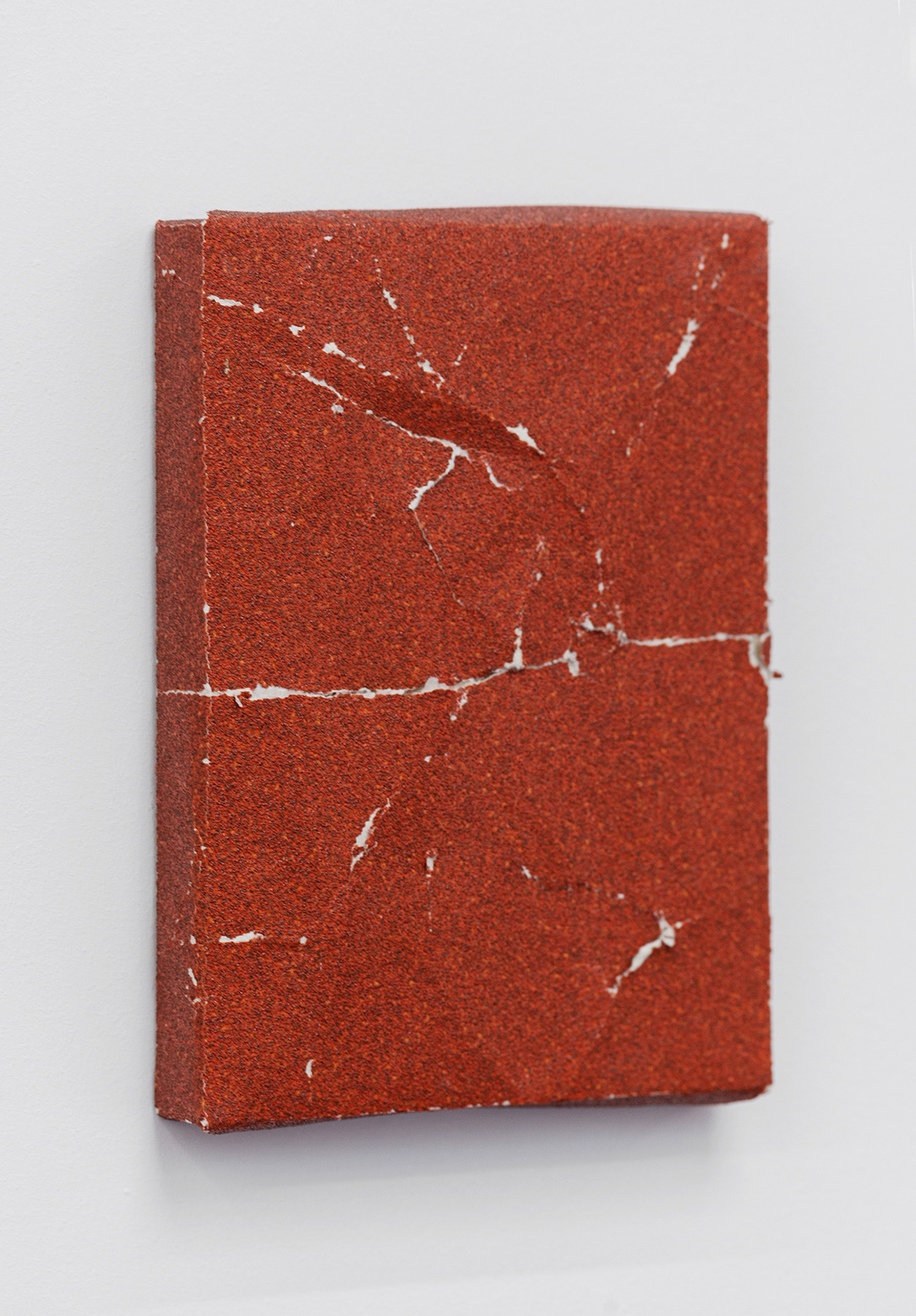

The show revolves around a material that’s very simple that I’ve been using for years, which is sandpaper, whose whole purpose and existence is to destroy, and this plays into what I’m trying to do—to find really what destruction is. So, the show is this really large installation where people can walk on it, where we destroy the piece by walking on it, and slowly destroying the sandpaper that way—it’s a two-way destruction going on. I really like that cycle. There’s about 50 or 60 paintings that are very small, about 6 x 8 inches, that will be hanging on the walls that are the destroyed sandpaper, too. So, it’s like destroying the destroyer.

I liked it because of the association of sand, and the reference of sand at the park and desert, and your surroundings with Turkey and all the issues that go with that. Have you worked with sandpaper in a traditional way before this? To actually shape wood?

Not really. But it’s a funny story—I met this guy at a party and I asked him what he did and he said his family owned a sandpaper factory. So, he dealt a lot with sandpaper. That’s actually how it started, which is kind of ridiculous. We nerded out about sandpaper, and in this circle of friends I didn’t think anybody knew anything about sandpaper—it was weird that I use sandpaper and knew so much about it. He actually took me to the factory on a tour and showed me how they make it and all that.

Did you collaborate with him and the factory to make this piece?

Yes, actually he’s giving me some of the sandpaper as a gift.

It’s enormous.

Yeah, it’s enormous—these things are giant. I got one delivered to me in Vermont last year. It came in a FedEx trailer and I was like, 'What the fuck did I do?' It was like, 300 pounds, 100 yards long and 65 inches wide, and it just comes on something like a toilet paper roll, which they call a jumbo roll.

You accidentally ordered one without realizing the size?

It wasn’t an accident—I knew how much sandpaper I was getting, but I didn’t realize how heavy it was. I’ve always dealt with small pieces of sandpaper, like letter size, and I didn’t realize how much weight it really had. My studio was on the second floor of this residency, so I had to get two other friends to help me bring it upstairs—it was ridiculous. Then, actually going to the factory after the residency, I got super interested in the factory processes and the making of the sandpaper, as well. So, I started to use the backside of the sandpaper to show the imagery there. There's this guy with a helmet, and gloves, and an axe, and protection gear on the back as a kind of instructive branding, and how it's to be handled within the factory itself. I would've never noticed that if I hadn’t visited the factory.

It’s interesting to think about sandpaper being destructive, just because it’s such a slow process—almost like erosion.

What I define as destruction is change of form: any change of form is a form of destruction. And that’s what I mean when I say I’m trying to really find what destruction is, and what it could be.

So, it’s not destruction insomuch as it eliminates an object as much as it transforms it into something else.

Exactly. Peeling a banana is destruction to me, too.

It’s kind of like what Umber sad when she said that a nuclear warhead finds its fullest form in the fact that it explodes. Now, you also founded some kind of destruction company as well, right?

Yes, I started a company back in 2010. I founded it right after [I finished] school—I came back from London and we founded this space where people would come and pay to destroy things. You may have seen a lot of them popping up right now, like ‘rage rooms’ or ‘anger rooms,’ and stuff like that. The thing is, when I was in London, I made this piece where the viewer became a part of the work by destroying it, and it was this slow destruction of the cement cubes that I made. The feedback I got from them was very positive, but some people also saw it as very taboo, to do something like that in public.

Is this something you started looking into when you were still in school?

Yes, this was a piece that I did in school, but what came out of that piece was the company—I wanted to make a space where people felt comfortable destroying things, and where it was okay to actually destroy them. We provided a safe space for you to destroy something, and there were three ways for us to find items for you: we had inventory you could choose from, or we found specific items for you, or you could bring your own things to destroy. To this day, it’s a very interesting experience to just be like, 'One day at 2PM I’m going to destroy this giant vase, and it’s not even out of anger—it’s just because I want to do it, and I'm able to do it,' and that's still very interesting to me.

I have to admit, there is definitely a catharsis in destroying things. I got really mad at this guy once, and I took this cheap vase that was really pretty, but I kind of hated it, and I threw it out the window and broke it—I was like, ‘I feel so much better!’ It was crazy. Have you ever broken something in anger?

The thing is, not really. I feel like if you do it in anger there’s a satisfaction level that goes really high really quickly, and then there’s the downside of, ‘Oh shit, what have I done?’ It doesn’t always happen, but I think I’m also a little bit of a control freak and I always test myself and my sense of control—so I have never done it out of anger, but the level of satisfaction you get when it’s planned is very different, I imagine.

So, you were interested in this series of emotions that you go through—satisfaction, guilt, anger as a prompt. I keep thinking of anecdotes—I had this friend who completely smashed her phone to pieces, and I always think of this because we went to this party to meet this boy—it’s always about boys, isn't it?

Always, always, always.

There’s actually this Rihanna song called ‘Breakin’ Dishes’—there’s this tradition of women breaking dishes. Do you feel like you tap into that? Did women favor your destruction company?

Honestly, we didn’t last long enough to get those kind of statistics on it, so I can’t really say. I actually made a couple of videos after the company, like video art basically, of people destroying various things. I met this woman through this project and she brought these plates, and she wrote things that she remembered from her recent divorce and destroyed them on camera, and I thought that was very powerful. The plate is definitely very common—I don’t want to say common, actually, but it’s almost like a choice—I don’t know, it’s very domestic in a weird way, a plate, but it’s also very fragile—you don’t have to do that much to destroy it.

I always think about how easy it is to break things and how long it takes to make them. Like, food — it takes so long to prepare food, and then you eat it in five minutes, it’s crazy. So, even eating is destruction.

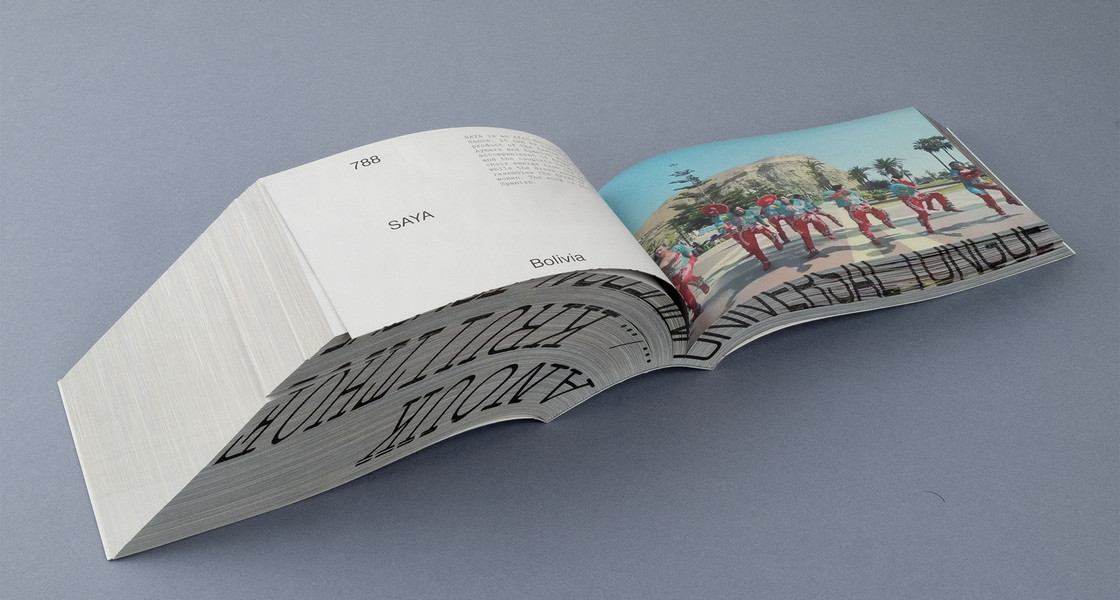

Definitely. I cook a lot and I know exactly what you’re saying. Like, I cook for hours and hours for my friends and then in 15 minutes everyone’s done eating. I’ve always found that really weird. I eat very simply because of that—I just don’t want to spend all that time and then only enjoy it for a moment. But it’s funny, because I feel like all art is like that—it takes so long to put a show together, or a piece together, and then you just look at it and move on. Films are that way, books are that way—it takes years to write a book, or to put together a film, and then we consume it so quickly. So, it’s just an interesting connection to destruction. I think about it all the time.

Yeah and eating is also avery primitive act—the most primitive act, in a way. It’s kind of like everything is destruction.

Yeah, when you start to think about the scope that I have with this subject—I see destruction all the time, every day. It could be anything. Like, right now, I’m in the living room, and there’s a blanket that’s not folded. To me, that’s almost like destruction, because it’s not in the sense it’s supposed to be.

'Number 3: Grit' is open now through December 29 at Pi Artworks Istanbul.

Photos courtesy of the gallery.