Odd Man Out: Jasper Sharp

Since 2012, the museum has invited a well-known artist to complete a two-year “residency” of sorts to curate their own show at the museum. Over the period, the museum’s “insides” are completely exposed to these guest curators, in which they are allowed free reign of the museum’s collection of about four and a half million objects, from Old Master paintings to Greek antiquities and everything in between. While past curators have included Edmund de Waal and American painter Ed Ruscha, the big unveiling comes on November 5, as filmmaker Wes Anderson and his partner Juman Malouf debut their curatorial exhibition, Spitzmaus Mummy in a Coffin and Other Treasures.

“I deal with the art of the last hundred years in a museum that deals with the art of the last 5,000 years,” says Sharp. “I’m sort of dealing with the last five minutes of what’s being made.”

On living in Vienna:

It’s not a straightforward city—it has it’s darkness. We have a landscape of museums, opera houses, libraries, which could sustain a city three or four times over. At the Kunsthistorisches, we have the greatest painting by Vermeer. You can go and stand in front of it and you’d probably be alone in the room for an hour before anyone walks in. We have the luxury of time and space. There’s a pace of life here, which I used to think was slow, but I’ve come to realize this is normal. I probably bump into a friend every day on the street and I have time to have coffee with them.

On the characteristics of Vienna’s contemporary art scene:

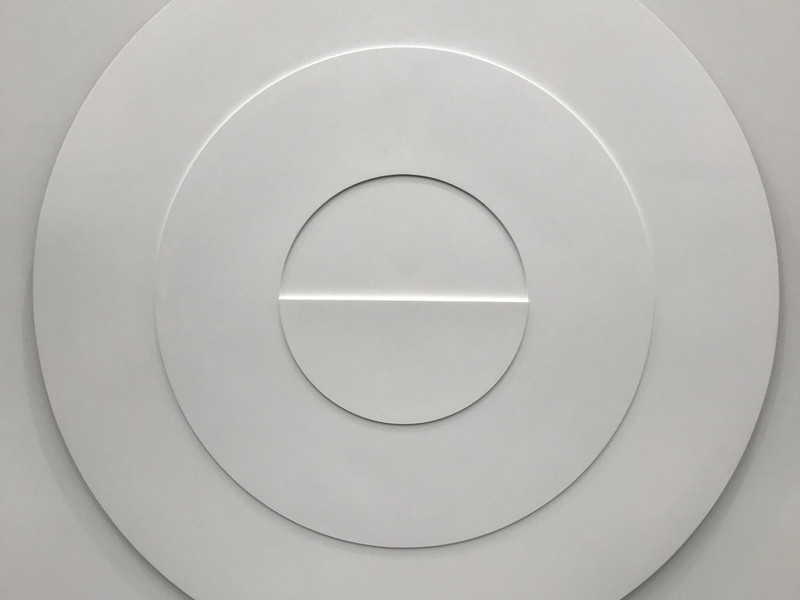

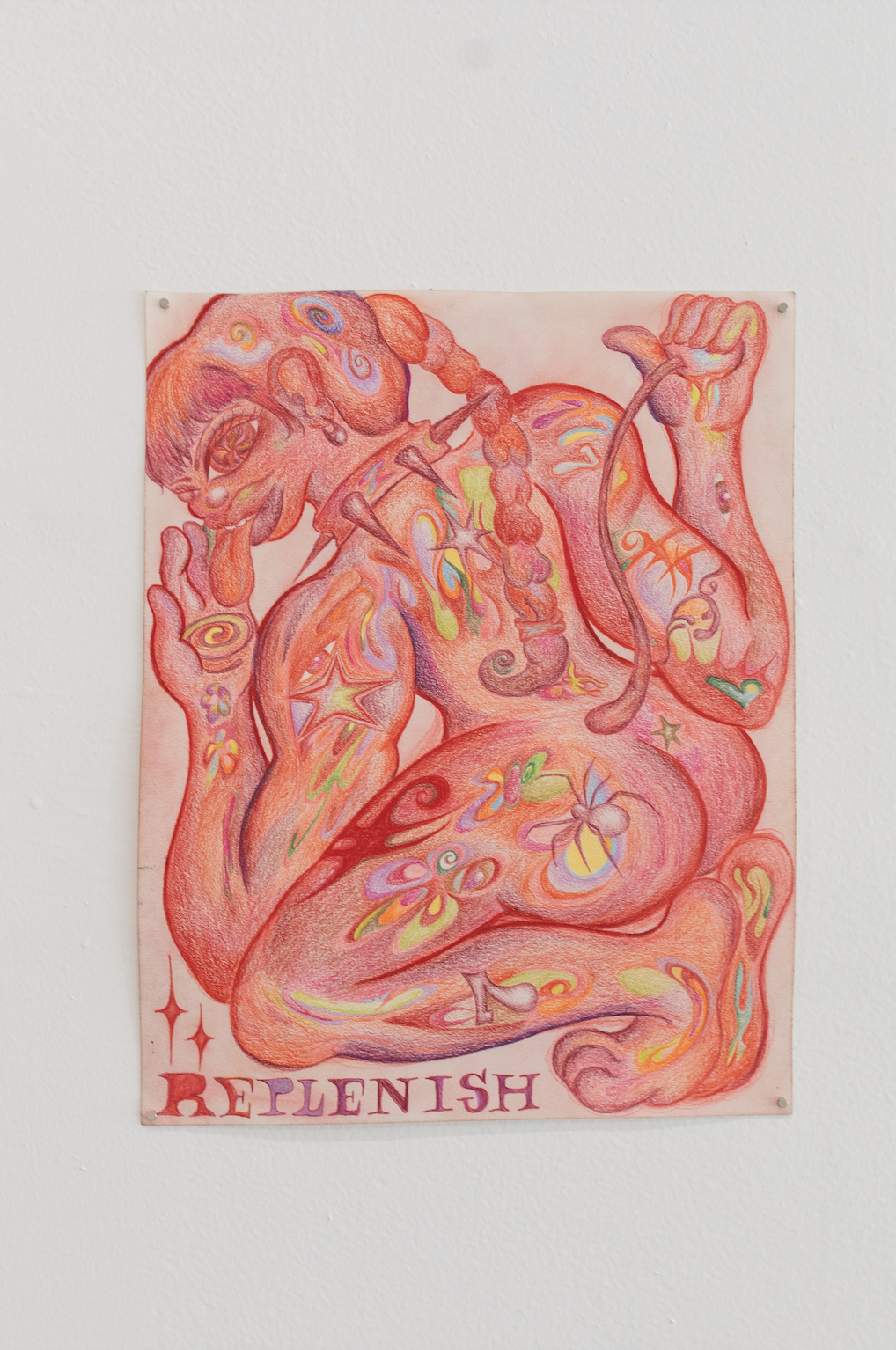

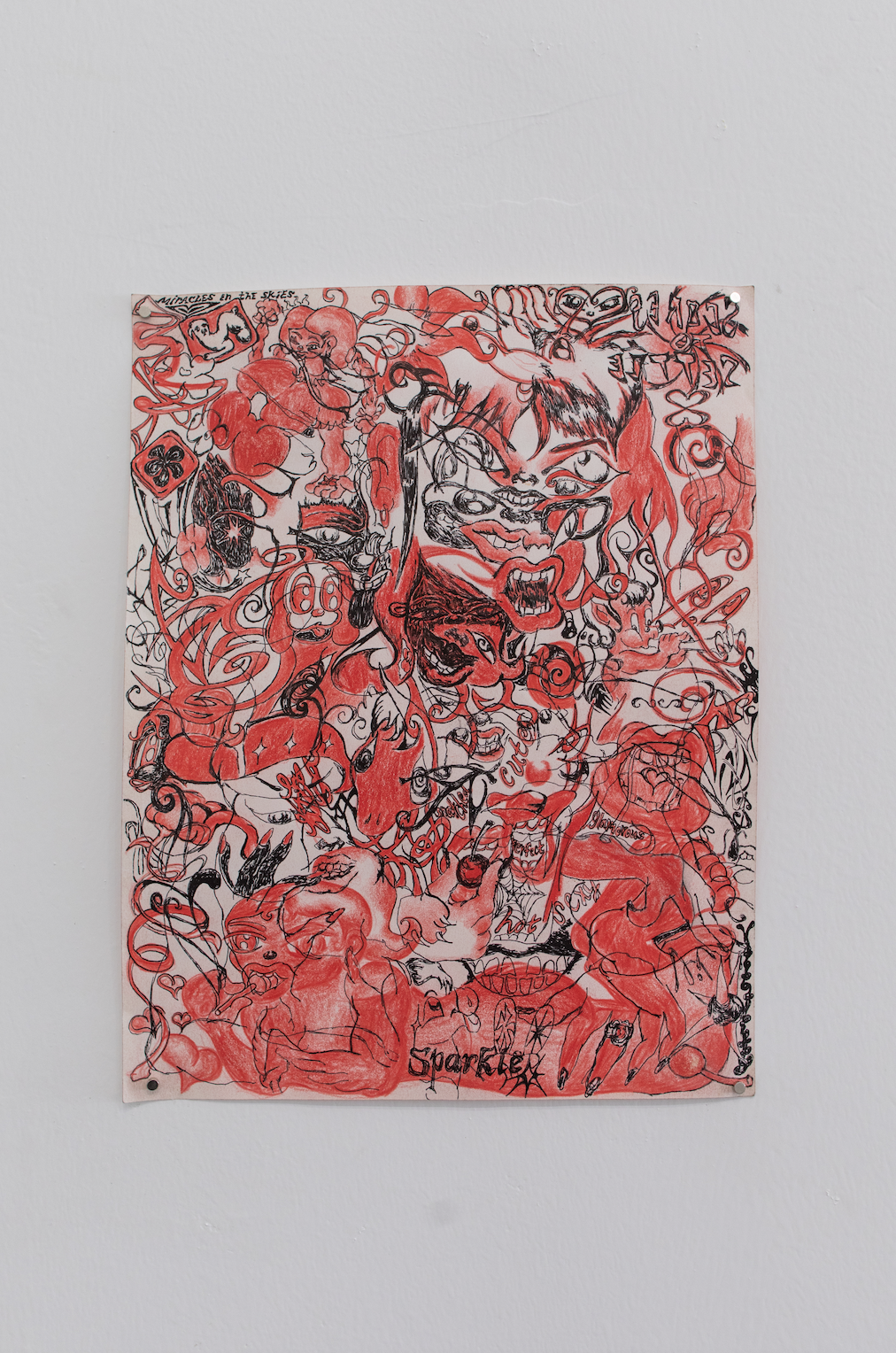

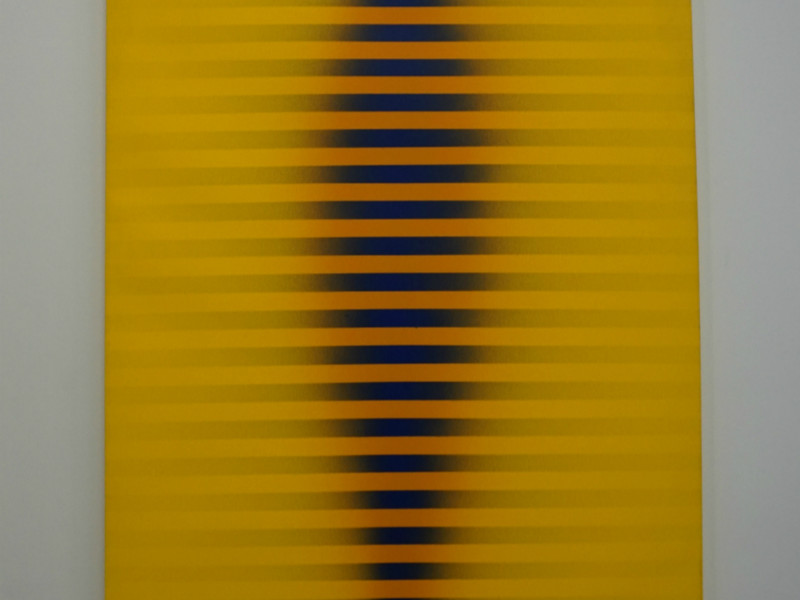

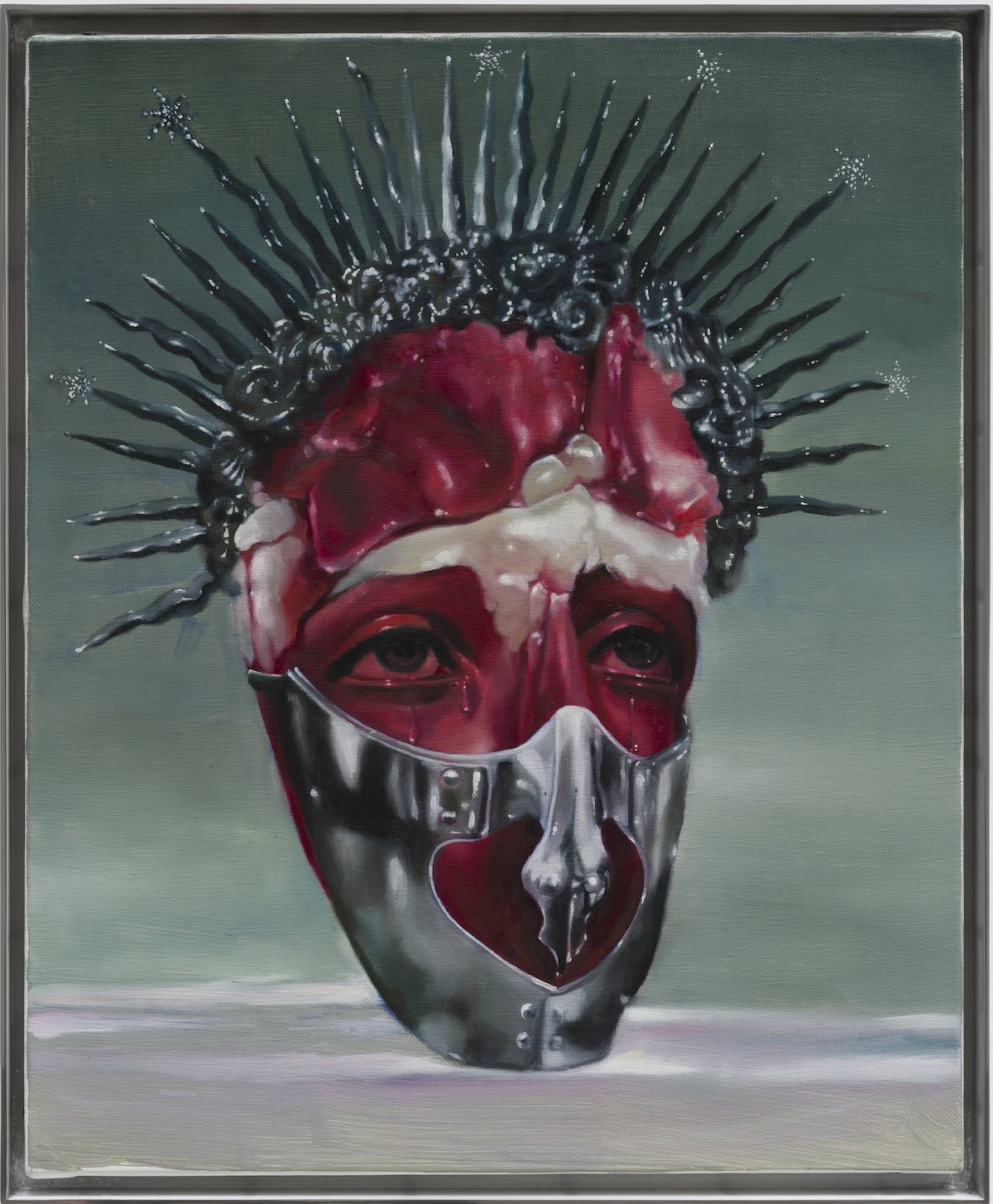

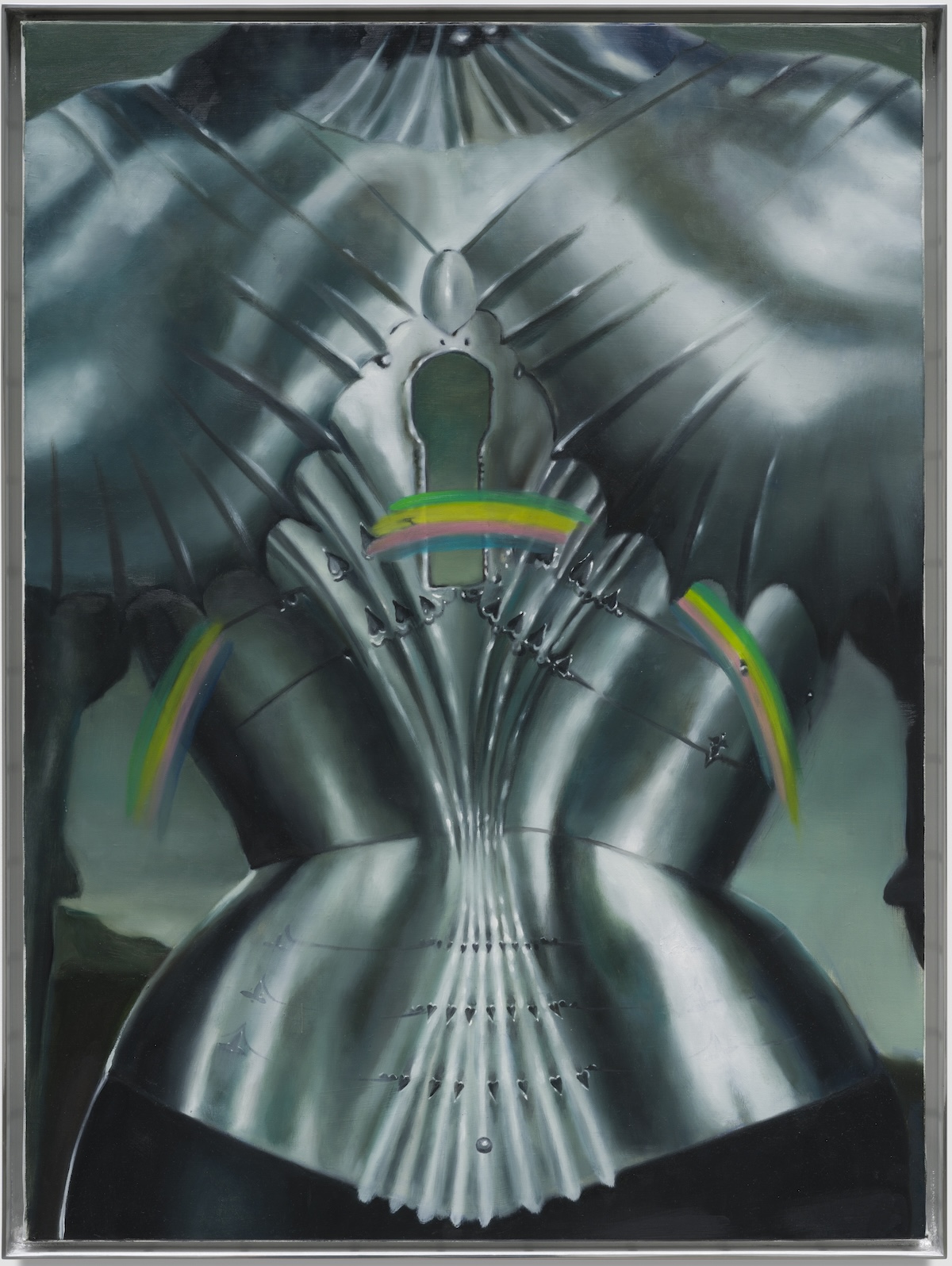

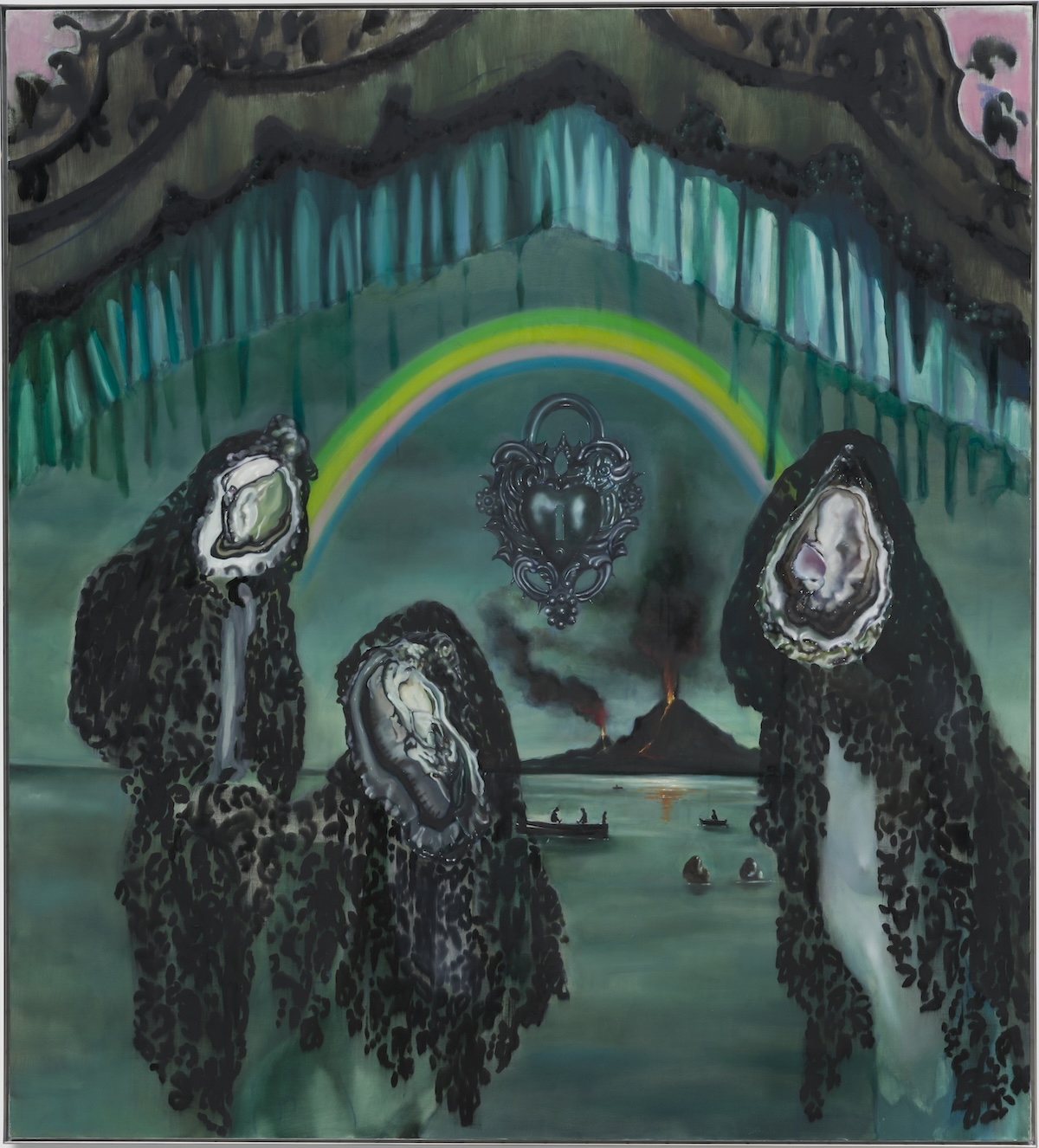

There’s a lot of cynicism. The two main strands of contemporary art that have come out of the art schools, on the one hand, [you have] a very bodily, performative, quite visceral, often quite sexual or fecal art, which is the legacy of Actionism, like Gelitin; on the other hand, a very reduced, cerebral, conceptual strand. They very happily coexist here. They are completely diametrically opposed to each other in terms of sensibilities for each other, but they both have a place here. I think you find that in a lot of places that have this historical “baggage.”

On working with Wes Anderson on his curatorial debut:

They’ve chosen 423 objects from all of our collections. Many of them have never been seen in public before. It’s a contemporary look at historical objects. They’ve pretty much laid eyes on most of our four million objects. He’s very thorough. The exhibition display they’ve done is completely bespoke. They’ve assembled the display of these objects with the same madness and pathology and hunger for possession that the Hapsburgs themselves had when they were collecting these objects in the first place. He selected the objects with very little importance for their provenance, their rarity, their size—all the normal “yardsticks” by which our normal curators judge objects. It was about the object and what does this object say to me—judging it by your guts or your heart, rather than your brain. He said to me once, “Is it any less important to like an object than to know about it?” To be able to respond to an object is a skill in itself. Feeling an object, you can’t learn that.

Read more about office's trip to Vienna here. Next Stop: to the 6th district to meet gallerist Nathalie Halgand.