Punk Lust

Onstage nudity and pornographic imagery on t-shirts and album covers was vital to the force of the scene. “It’s difficult to explain because today we’re so inundated with it that we’re numb to it,” says Becker, “but it wasn’t like that at all. Back then, you had to actually go to some special shop to buy [that stuff]. And as a young kid you couldn’t go there—that was for trenchcoat guys.”

Punk championed gender fluidity and artists like Cosey Fanni Tutti fused sex work with their art. In a way, it was a similar time to now—except way cooler, because there was no social media, which allowed for the existence of an actual underground.

Since taking over as creative director at the Museum of Sex in Manhattan, Becker has been planning to organize an exhibition around artworks and mementos, like t-shirts, patches, pins, flyers and zines from those early punk years, an ode to a time that set the stage—and perhaps even broke the barrier to allow—for the subversive artists, musicians and even social media personalities existing now. Exploring the movement’s use of sexuality as a tool for that kind of radical cultural change, Punk Lust: Raw Provocation 1971-1985 is on view now, through November.

office stopped by the exhibit to chat with Becker shortly before the new year. He told us all about the show and what it means to be a punk. Read the interview, below.

'Iggy Pop: Penetration, No. 10,' 1977, Fanzine. Toby Mott/Mott Collection; 'Penelope on Leopard,' 1977 and 'Plungers Take Broadway,' 1978, Ruby Ray. Courtesy of the artist.

When did you get into punk?

When I was a kid, I was definitely into Bowie, and Lou Reed, The Velvet Underground, and Iggy, and they had their looks. But then when the [Sex] Pistols came, it was just such a massive explosion for us. We were all in art school—I studied graphic design and just these graphics [they used], breaking every single rule I was being taught. So, I’m in school and they’re teaching us one thing, but the things I’m into are ripping it all to shreds. It was such an amazing moment to be there at that time.

How were people reacting to the sexual graphics?

It really shook us—that’s the only way to describe it. At the time, sexual imagery wasn’t present. I’d never seen hardcore porn at that age. Never. I was like 15, and had no idea what hardcore porn was. There were sexy girl images and whatever, but no genitals—but then they had it on t-shirts! It was fucking crazy. It was really outrageous and shocking at the time.

Why did you think it was important for this exhibit to focus on sex in relation to punk, specifically?

Because punk used sexual imagery as a means of provocation. It was really in your face and [about] breaking the rules, because it was forbidden at the time. Everything was so censored. It’s difficult to explain because today we’re so inundated with it and we’re numb to it, but then, it wasn’t like that at all. Back then, you had to actually go to some special shop to buy [porn]. But as a young kid, you couldn’t go there—that was for trench-coat guys. We just were not quite there yet—we barely understand why we were getting hard-ons.

What cities does this exhibit cover?

It’s about the exchange between New York and London, because that’s, early on, where it really happened. But there are a couple of pieces from San Francisco and LA. New York at this time was almost bankrupt—’77—and London had the worst labor crash, and people were totally desolate and desperate and angry. So, I remember going to London and being like, ‘Whoa.’

Just because of the punk scene and the energy?

It was just so different. I grew up in Switzerland which is very middle-class, boring, dull—but relatively wealthy. Whereas in England, you saw people that were poor, which I didn’t know [existed], and you have a strict class system, so punk really spoke to that—this disaffected youth. Malcolm [McLaren] really pulled the strings together, he pulled the narratives he saw in New York and brought them to London and pulled it all together, gave it a philosophical outlook. A lot of that came from Guy Debord from The Situationists. So, these are very rare artifacts.

'Sex Pistols: Anarchy in the U.K., No. 1,' 1976, Fanzine, 'Glitterbest' and 'Sniffin’ Glue, No. 8,' March 1977. Toby Mott/Mott Collection.

How do you think the internet has impacted the way music or cultural scenes are formed?

[Back then] images weren’t shared the way they are now. So, you took a picture and it was yours. Maybe a couple of your friends saw it, but that was it. It wasn’t like now, where everyone has followers and likes—it’s a completely different world. Now, everyone’s an endless self-promoter, but back then, you just did this stuff with your friends. I think that also allowed for different things to flourish and take on their own shape, because you weren’t always seeing what everybody else was doing. You were in your own head.

So an original scene could actually emerge.

Yeah, within its own. Which is so interesting because when you travel, and you go to these places that were—I’m not saying hermetically sealed, there were always trade routes and stuff like that that [allowed for the exchange of] culture and ideas and products from place to place, and that’s important. But still they were allowed to be on their own. In Europe, you still have that—you go from this country to that country, and each has its own flavor. But now, it’s becoming like everybody listens to the same thing everywhere and has the same ideas and everything’s one big Pinterest board, basically. There’s just no more underground, because nothing is underground. Everybody immediately publicizes what they do.

In New York, where do you think punk lives? Do you think it’s still here?

I don’t think it’s in New York. I can’t imagine that you can still do that here—it’s totally changed. Part of it is to be an outsider, and embracing that idea of being an outsider. So, you have to be outside to be an outsider. But back then, when I came to New York, downtown was empty. It was a wasteland—there were empty storefronts everywhere. It was basically like being in the middle of nowhere. Like Buffalo, almost. I think Buffalo is much more punk now than New York City. If you want to be punk, you’ve got to go there because [NYC] is a shopping mall. Straight up.

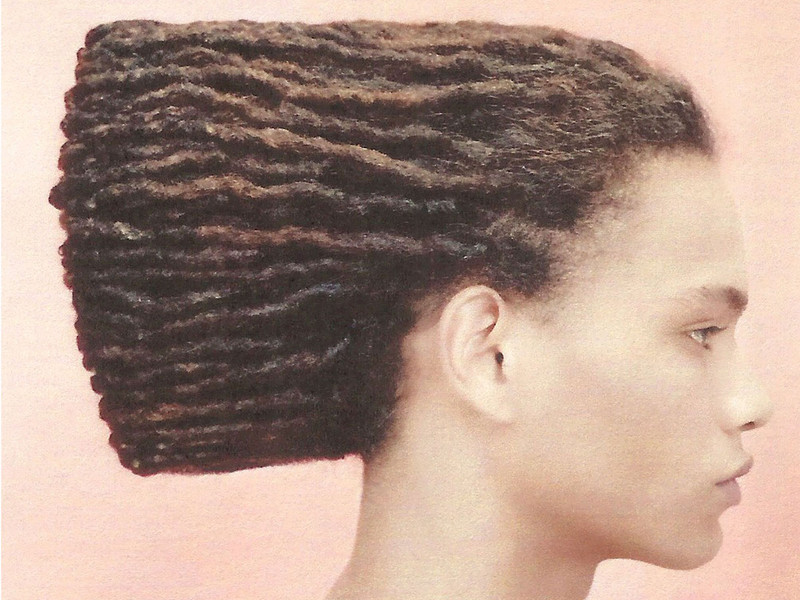

How would you say punk has evolved over its lifetime, now that there’s a thriving queer scene in New York and a slightly more open mainstream embrace of gender fluidity?

This [exhibition] is about that—about gender-bending. I think punk did that, as well, and disco obviously even more. It kinda went back into the closet after, and now it’s coming back out—thank god it is. In that regard, I think we’re in a really good moment, where people are just open. But the thing that’s so annoying about it is the language police around it where it’s like, ‘Just shut up.’ It’s the opposite of punk. It’s trying to make rules of what you can say and what you can’t. And that’s so not punk, like being a rule-maker.

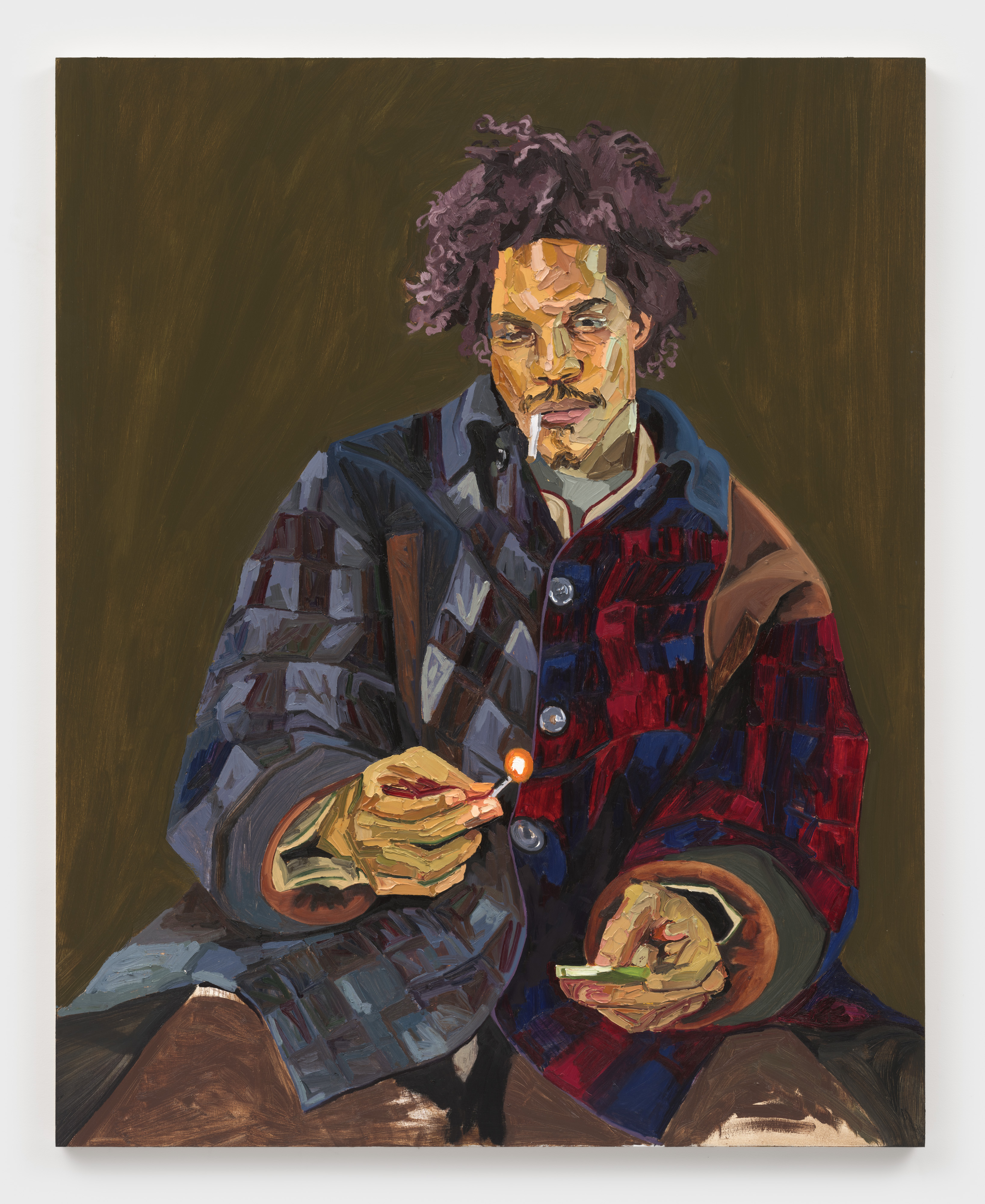

What is punk about, for you?

A lot of it was the freedom to just express yourself and not need to be perfect, and to have this immediacy and honesty, as opposed to trying to make it the most perfect thing in the world. To not be a connoisseur and not be this perfectionist—it’s DIY. That, for me, was the big thing I really liked. There’s always some room for that—to express human imperfection, because there’s always going to be people who connect to that element. There can be these super highbrow polished things that are amazing, and then there can be the things that are completely falling apart. They’re still amazing, as well.

‘Punk Lust: Raw Provocation 1971-1985’ is on view now through November 30, 2019 at the Museum of Sex in Manhattan.

Lead image: Joey Ramone and Debbie Harry, Robert Bayley, 1977. Courtesy of the artist.