Shocking violence, mutilated bodies, and decaying bologna: the Whitney Biennial asks you to face discomfort

As the first major art show to respond to the tumultuous events of the last six months, the 2017 Whitney Biennial could have easily gotten stuck in layers of academic and political discourse. Instead, Yew and Lock chose to let the art speak for itself. The wall-texts are few and far between, the single-paragraphed descriptions are unclouded by scholarly references, and the show's diverse pairings of art across all mediums feel intuitive, playful, and sincere.

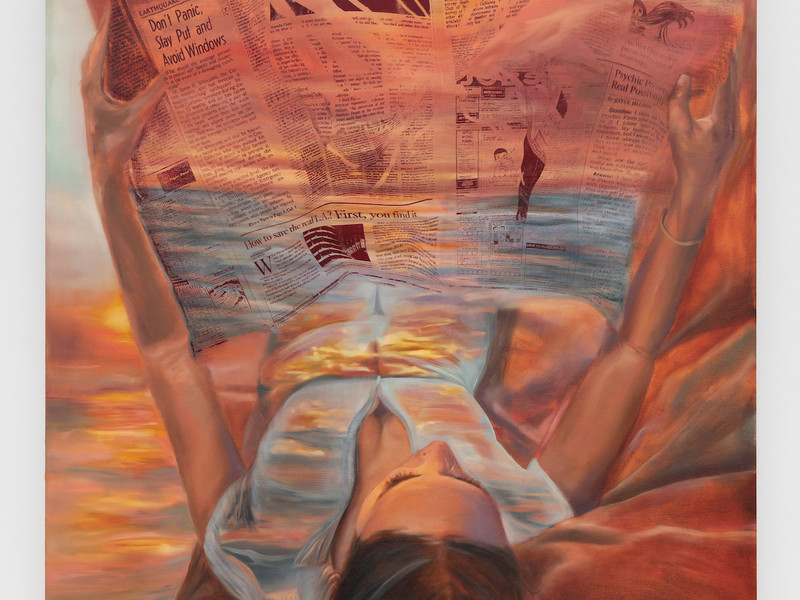

Wherever you look, the artwork stretches luminously towards the future or it broods darkly over the past or it writhes furiously against the present moment, but whatever it does it does so earnestly, rapturously, with a sense of urgency impossible to ignore. One gallery screaming with such exigency is the pairing of Henry Taylor's paintings and Deane Lawson's delicately staged photographs. Among these powerful portrayals of the contradictions and tension of being a person of color in America, Taylor's chilling painting of the police slaying of Philando Castille stand out. Lying fatally wounded in his car seat while the police officer is still holding up his gun, we see the dying Mr. Castille from the perspective of his girlfriend, Diamond Reynolds, or maybe from the perspective of us all, the collective hivemind, who watched his final moments on our phones and laptops. Furiously titled THE TIMES THAY AINT A CHANGING, FAST ENOUGH!, Taylor's painting touches upon themes of political upheaval, racial conflict, and technological expansionism that flows through much of the biennial.

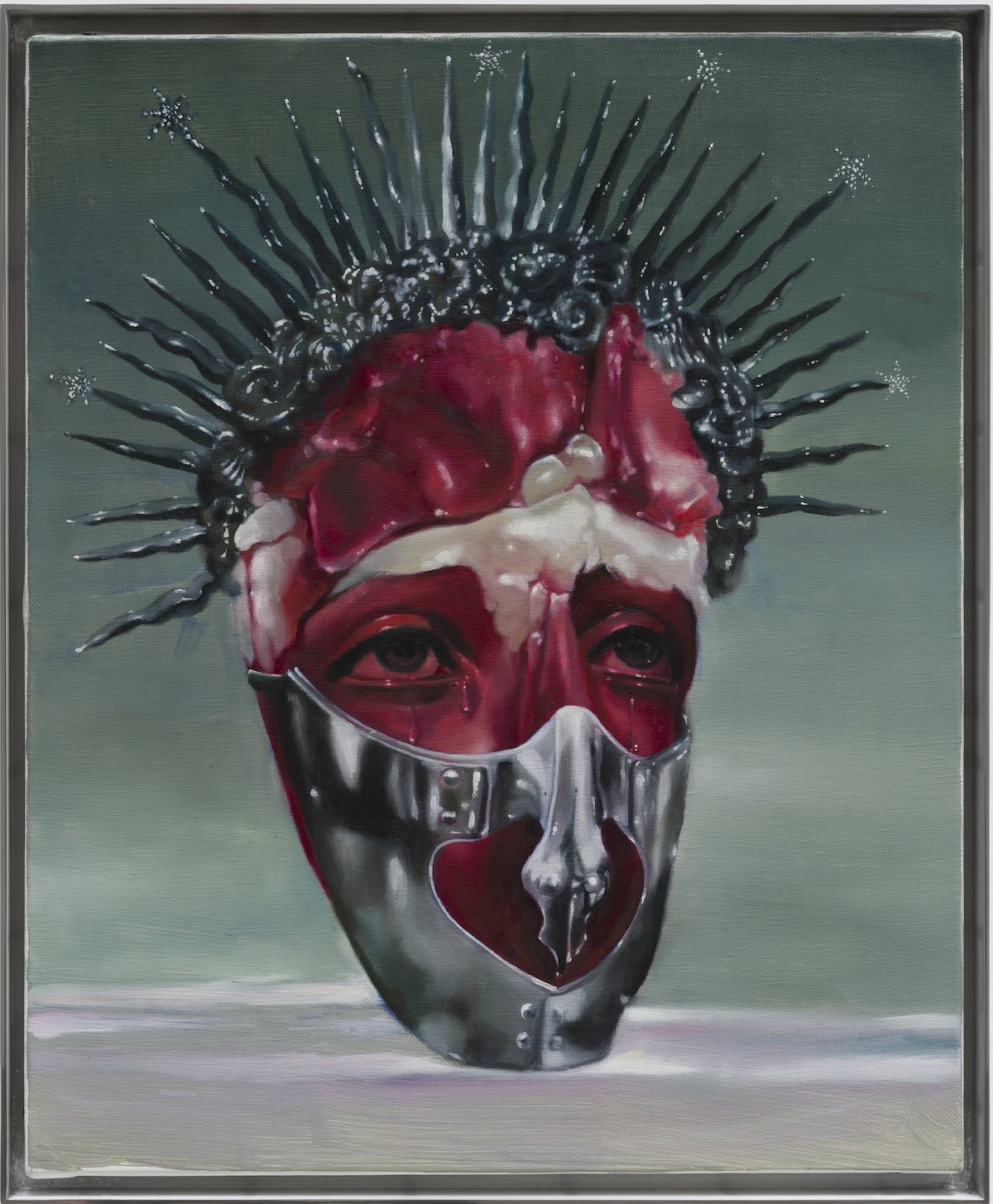

Continuing the sinister tone are two works that use the disturbing image of a mutilated face. One is Dana Schutz' Open Casket, a historical painting interpreting the famed photograph of 14-year-old Emmet Tilll lying in his casket, his face bloated and disfigured, after the brutal lynching that helped spark the Civil Rights movement. The piece is generating some controversy—Schutz is yet another white artist who will profit from a depiction of black death. The other is Jordan Wolfson’s sickening virtual reality video Real Violence. Before donning the VR headset, museum staff ask viewers to hold firmly onto a metal bar to help steady themselves through the 90-second video. It shows Wolfson smashing another man's head with a baseball bat, kicking and stomping on his face in a shocking display of violence that even the most sadistic video games will skip. The artist was beating a robot, but it's so lifelike that it is nearly impossible to tell.

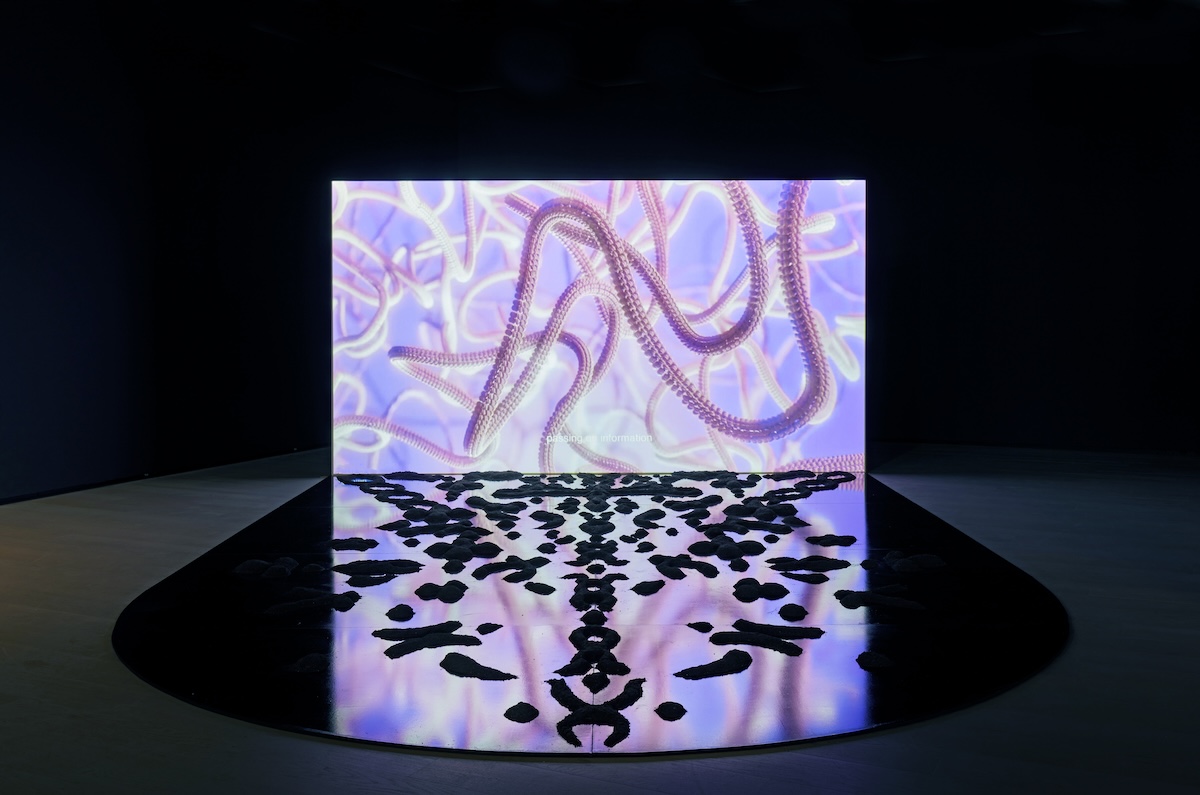

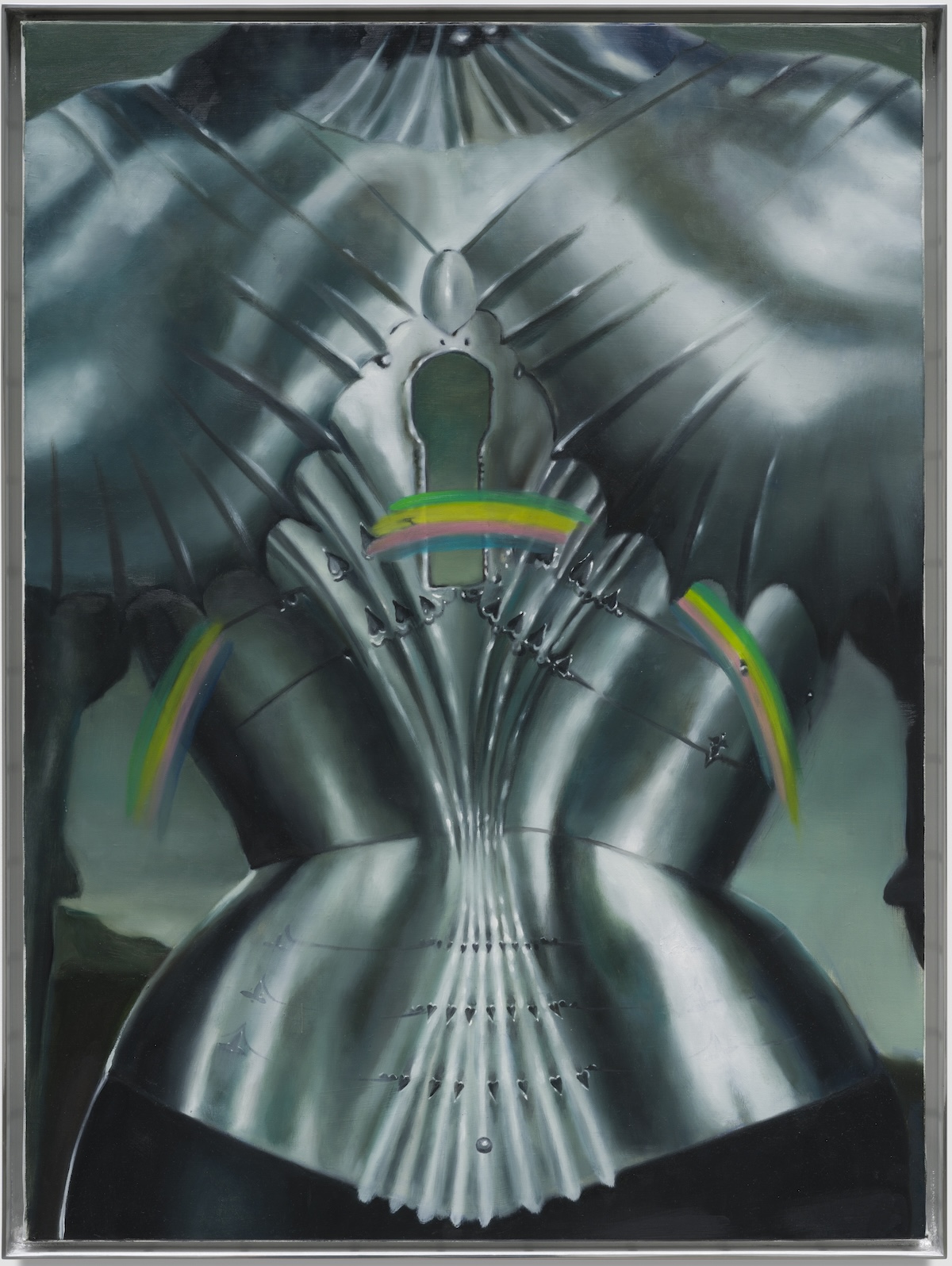

In a room furnished with plush pillows, Anicka Yi’s mesmerizing 3-D video The Flavor Genome—the most visually spectacular work in the show—also gives off a sinister feel. The film's protagonist meanders down the Amazon on a Conradian hunt, not for ivory, but for a new plant or genome that will satisfy our incessant, consumerist cravings. Octopus tentacles sucking away at human flesh, shiny fish eggs, fruits penetrated by syringes, and blue smoke emanating from an impaled chicken are some of the striking images that emerge from the screen as Yi puts the 3-D technology to exhilarating use. The biennial is worth a visit for this film alone.

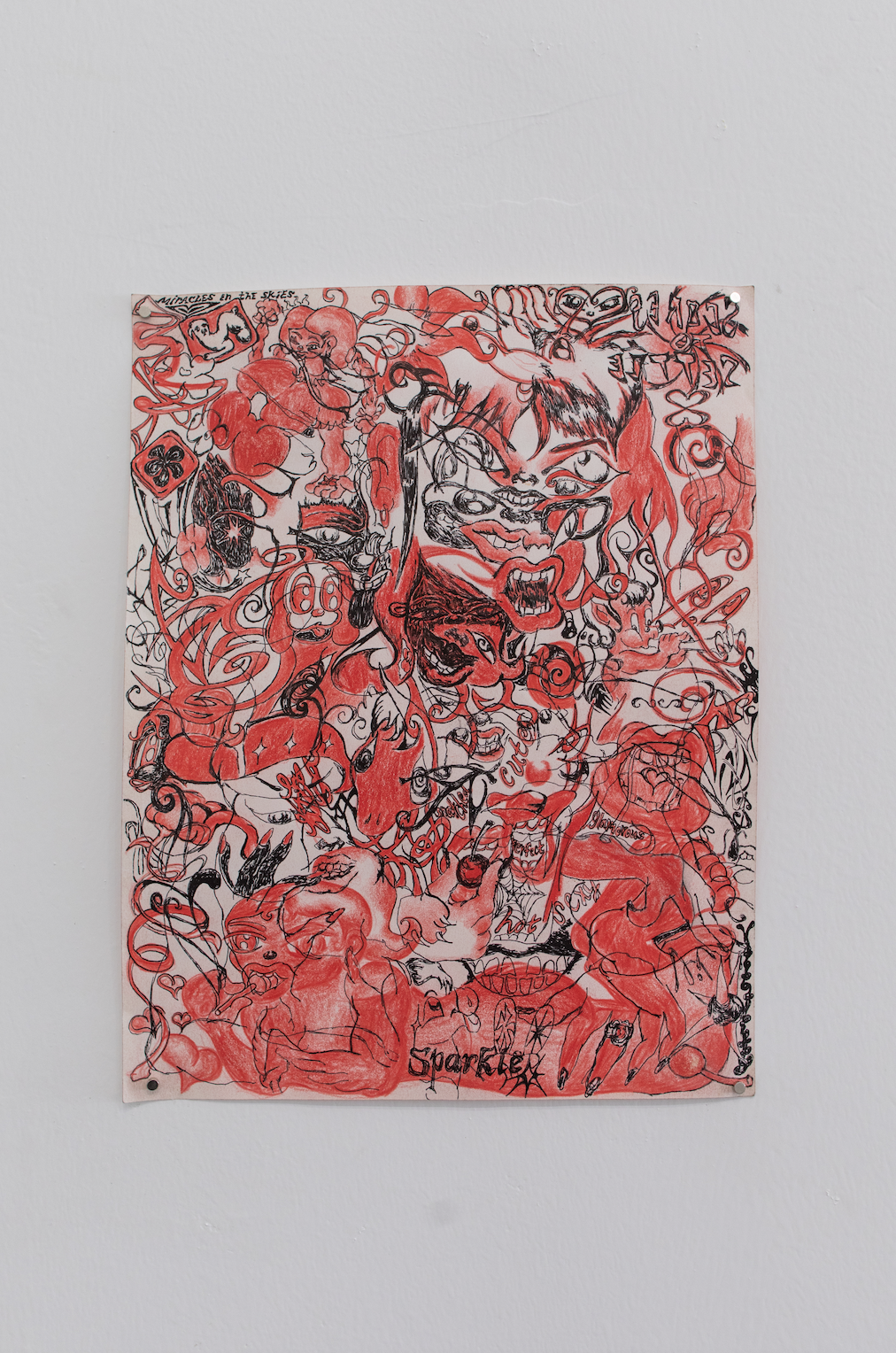

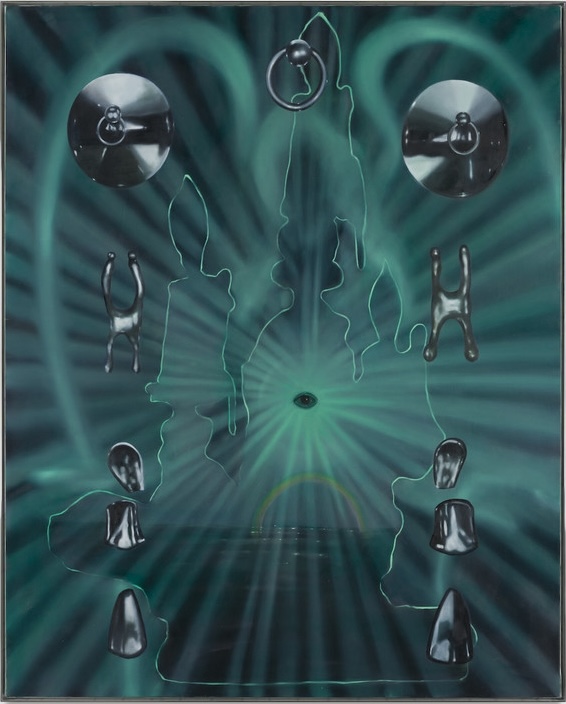

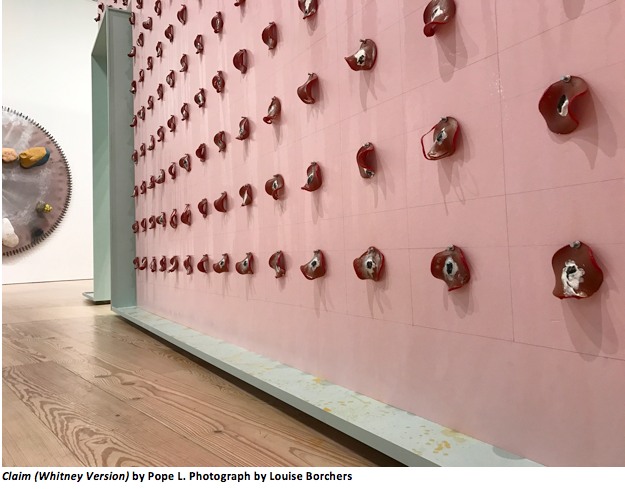

The bleak outlook of America continues in Tommy Hartung’s The Lesser Key of Solomon—a nightmarish video played to the soundtrack of Nation of Islam member Leo Muhammad’s raging speech against racism and inequality—and in Pope.L's Claim (Whitney Version), an installation covered inside and out with a meticulous grid of bologna slices with a small photo of a person affixed to it. The bologna slices are dripping, weeping with glistening fat, “mourning a haunted order, a ghostly category, a soggy practicality, a floppy commonsense,” as Pope.L writes in a haunting poem attached to the wall. Over time, the meat slices will curl in on themselves, the portraits will slide off, and the sickening smell of decaying meat, real or imagined, will sit in your clothes for the rest of the day. And if you haven't had enough darkness, there is more to be found in Ajay Kurian's Childermass, a series of childlike figures crawling up a rope in the stairwell dressed in t-shirts with the tagline “ALL HOLES MATTER,” or with the silhouette of the Twin Towers and a scrawl in Arabic spelling out “The age of ignorance.” Above the childlike figures sits a chrome chameleon figure, reigning over the museum like some tyrannical Lovecraftian demi-god.

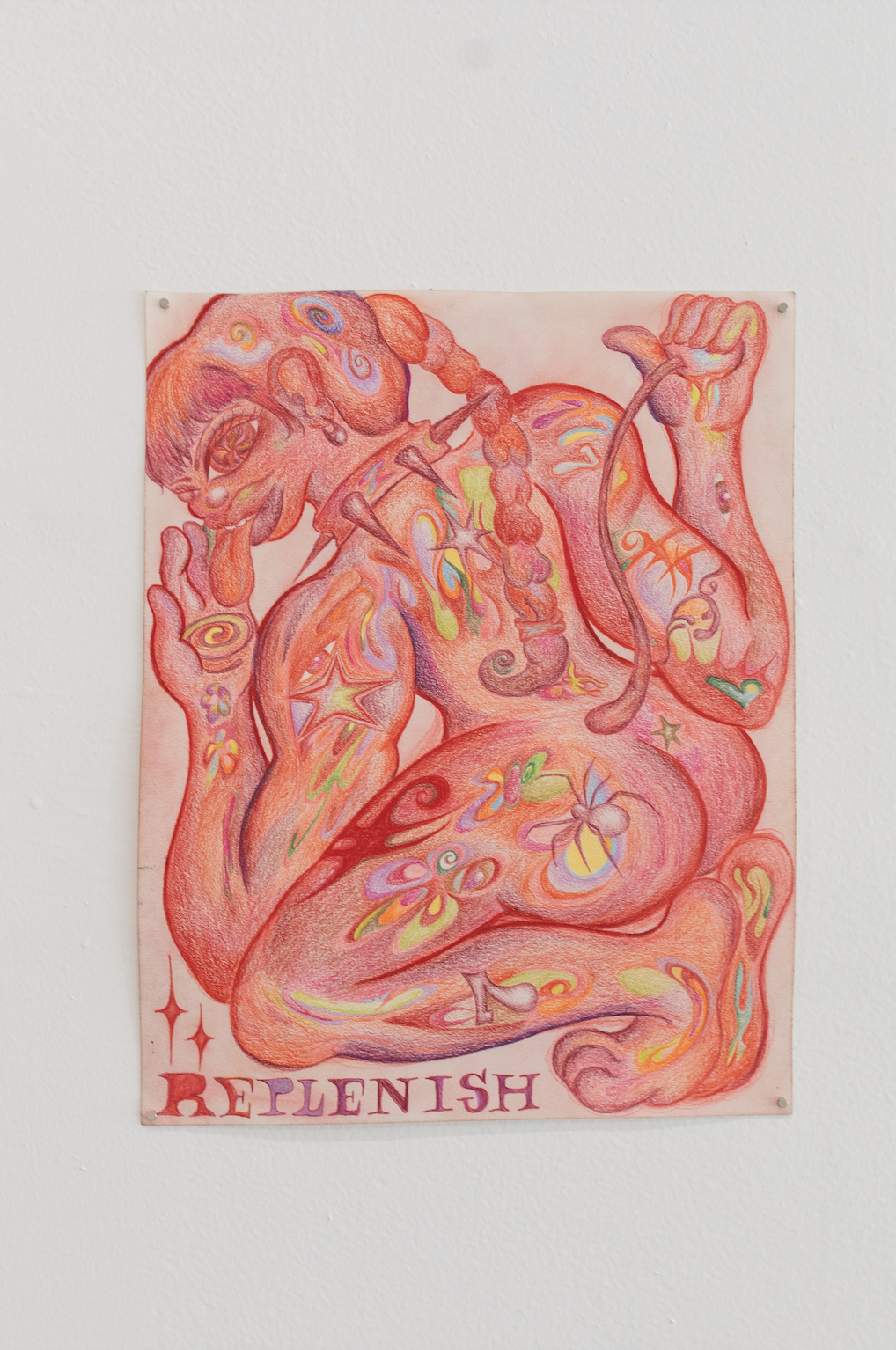

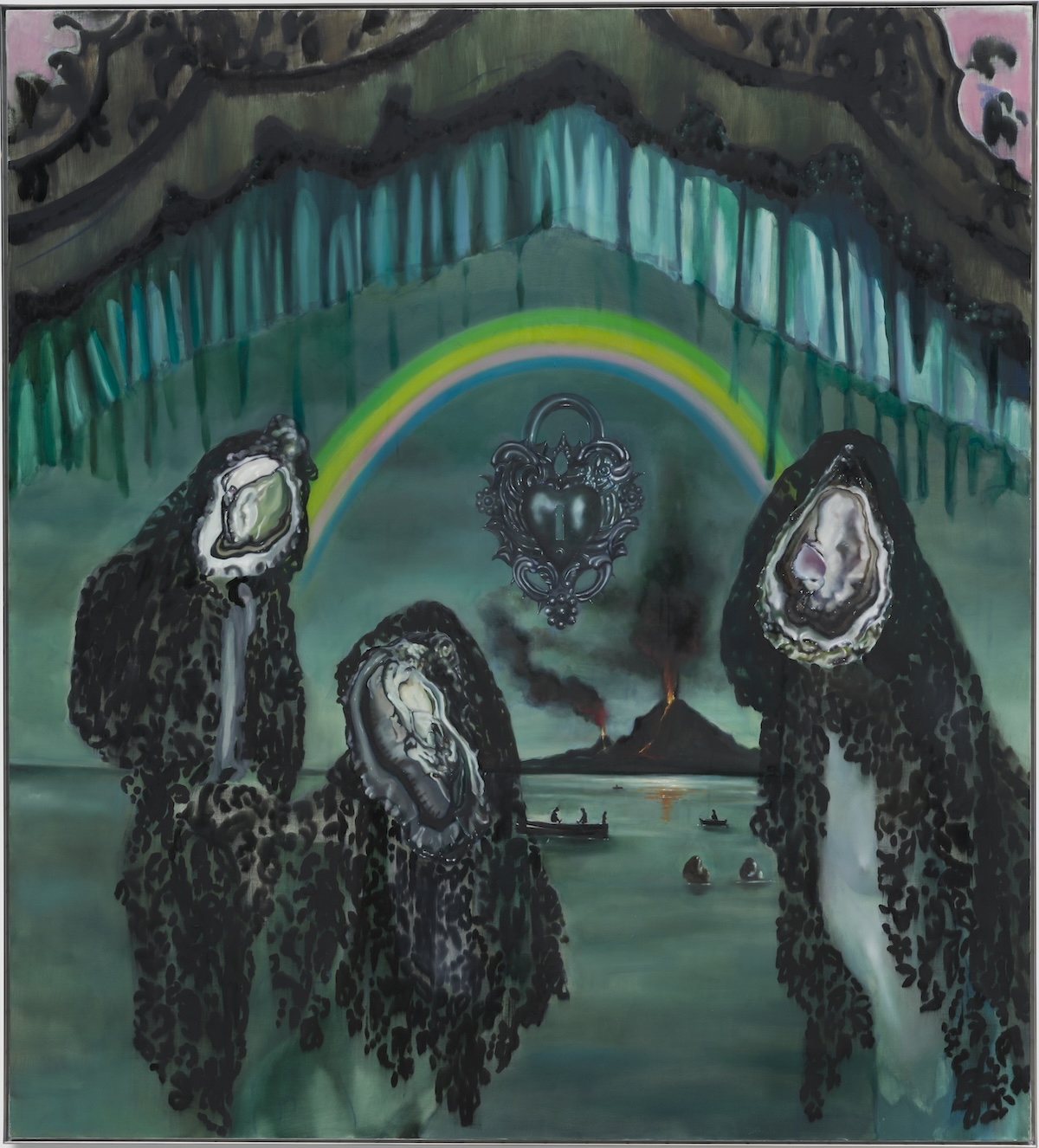

However, not everything is gloomy. The curators have poked holes in the dystopian fabric where light shines in, literally and metaphorically. On the eastern facing windows Raúl de Nieves has installed stunning faux stained-glass made of acetate sheets, coloring the room in glow that is somber and ceremonious, yet also alive with the glee of one-dollar shop gadgetry. At the preview, audience members took in the colors and scenes from the couches placed along the walls, and somehow conversation seemed lighter, more hopeful, when cast in the light from Nieves' mirthful fantasies.

In several other works, the show uses the Whitney's natural light to gorgeous effect. One floor above Nieves’ work, Azad Raza has placed Root sequence. Mother tongue, an installation of twenty-six youthful trees placed in wooden boxes with one full-time caretaker designated to each of the trees. The room is alive with the small-talk and personal knickknacks of the caretakers, while the frail flowers and branches of the trees seem to peer out of the windows, beckoned like all youth by the shiny towers of Manhattan. Outdoors on the sixth floor terrace Larry Bell has installed Pacific Red II, a stunning dotted line of sculptures built from sheets of glass in varying hues of red so subtle you barely notice: darkest where the roof is shaded in the morning, lightest where the sculptures are fully lit by the morning sun.

On the western side of the Museum, Samara Golden has turned the Hudson River view into the The Meat Grinder's Iron Clothes, an uncanny hall-of-mirrors installation of miniature rooms that seem to reflect the dreams and nightmares of American class-based society: the luxury rooms and hotel spas of the upper-class are mixed with the gyms and corporate offices of the striving, stuck middle-classes, and the dirt-caked, doorless toilet booths of the mad or incarcerated.

America is at a bleak spot, the Whitney Biennial seems to propose, and we should sit with the discomfort a little longer. Behind the ticket counter, Park MacArthur has installed Another word for memory is life, two brown aluminum plates with the look of freeway signposts positioned to block out the Museum's informational screens. Apparently, no one will tell us how to find our way out of the darkness.

At the end of Anicka Yi's wondrous film, the expedition crew has mysteriously died and the protagonist is the lone survivor lost in the rainforest. The botanist explorer seems unfazed. She gathers supplies, pushes a limp body off a boat, starts the motor and head up the river alone, pushing deeper into the jungle. Wherever we go from here, it seems, we must pioneer into the unknown, light up the darkness, chart a new path. Luckily, these artists are already well at work.

Lead image is a still from The Lesser Key of Solomon, 2015, by Tommy Hartung. Ultra-high-definition video, color, sound; 8:05 min. Courtesy the artist and On Stellar Rays, New York.