Slava Uncensored

Long before same-sex marriage was legalized anywhere in the US, Mogutin attempted to marry his then-partner Robert Filippini in Moscow, back in 1994. Faced with criminal investigation by his native country, he fled to the US where he was granted political asylum a year later. But his fight against bigotry didn’t end there; it followed him into the art scene. While he was targeted for his reporting and activism in Russia, in New York it was his visual art that was censored.

“[Censorship] used to translate into my works being physically removed from certain projects and shows and publications; I know I was banned from many media outlets,” Mogutin explained. So he started sharing work on the internet; at first, in a virtual gallery on Blogspot featuring queer artists, until that site started censoring him as well. “I just feel like the internet turned from the most popular and democratic medium into the most controlled one, and it’s almost a tool of oppression at this point,” he said.

As other sharing sites moved, like Blogspot, away from lawlessness toward seemingly arbitrary regulation, his work––a survey of identity, human nature, queer life and sexuality—continually got taken down. And to him, compromise when it comes to his art isn’t an option. “I never create images to fit the criteria being sold to us as ‘community guidelines,’ because I feel like I am the community and the people I represent,” he told office. “People who censor artists like myself are parasites, and they would be out of jobs if there was no content for them to censor.”

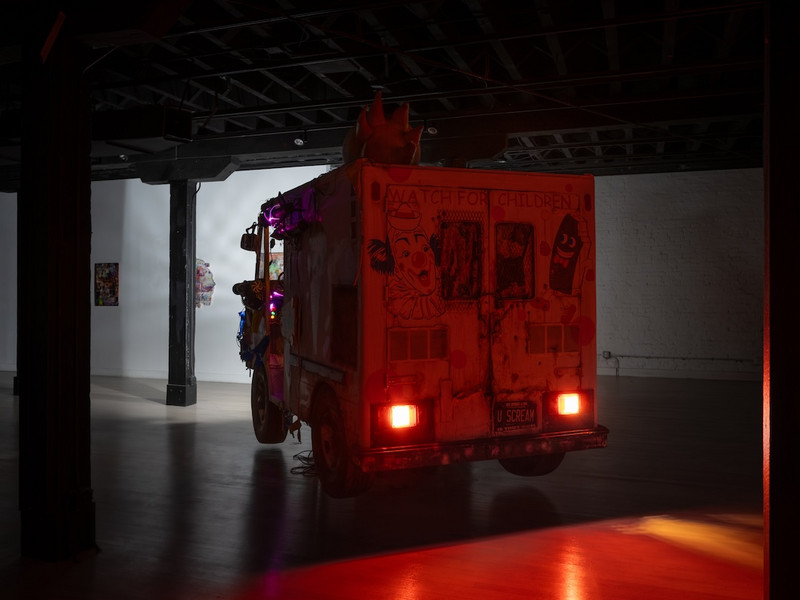

To him, the future of free expression is in alternative platforms—both on the internet and IRL. Sites like Tom of Finland store—on which Mogutin is currently exhibiting a show, “XXX Files”—and organizations like Queer Biennial create space for the content Facebook’s overlords would rather have wiped away. “Clearly the system allows more freedom for trolls and homophobes and bigots,” Mogutin said, “than people who actually create something original and radical and unconventional.” But luckily, the people are on Mogutin’s side. Apart from his Tom of Finland exhibition, Mogutin recently collaborated with Helmut Lang on a collection of sheer and graphic tops as part of the brand’s “Logo-Hack” series.

Read our chat with the artist about art-world politics and internet irony, below.

Conceptually, what is your mission?

I started in my teen years as a poet and journalist in Russia, and since I was the first openly gay journalist, the Russian media brought a lot of attention to my work and my personal story. I brought a lot of negative attention from the authorities, [which is] why I had to leave Russia. That background informed my work in so many different ways, because I do feel like I represent a certain community and group of people that don’t have representation in contemporary mainstream culture. I see myself as the commentariat of different subcultures and social outcasts, people that are considered marginalized by the mainstream culture.

How does your activism extend beyond your art?

I attempted to register for a same-sex marriage in Russia back in 1994, and at the time it wasn’t legal anywhere else in the world. So that was not the starting point of my work as an activist, but it was probably the main event that led to my exile from Russia. And when I received my asylum in the US as an activist, it became an important point for discussion and I also think it opened a lot of doors for similar cases. It gave people some sort of union––not just Russia, but other republics. I’ve done a lot of talks and interviews regarding discussion with gay rights in Russia nowadays. It went from bad to worse basically––when I left, the anti-gay law was already abolished but still homophobia prevailed in mass media and in mainstream culture.

I still feel very much connected with what’s going on in Russia. I follow the news, I have a lot of friends telling me what’s going on in the underground community and a lot of the work I do addresses the issues related to censorship and homophobia, not just in Russia, but really in America as well.

It seems like a lot of your focus, especially with the most recent work you’ve done, is on American censorship. So I wanted to ask about what you think of Tumblr’s recent ban on nudity and Instagram’s censorship.

It was not a big surprise to me that it happened. Because it was a result of the pressure from the new government regulations. It’s actually the same reason why Craigslist had to drop the personal ads earlier last year. It was kind of a chain of events, and the overall political and cultural climate created by Trump’s government is very much in support of censorship and cracking down on basic constitutional rights and freedoms, so I really see it as part of the larger picture. And also the fact that there was no regulation of adult material on platforms like Facebook and Instagram, which basically led to, on one hand, assuming freedom of expression, but on the other there was this arbitrary censorship with entire profiles being deleted and people being banned from various platforms, with no arbiter mechanism for them to appeal the decision and whatnot. So I feel it highlights the need for constructive dialogue about how this issue should be addressed in the larger culture and context.

Do you see censorship as a positive thing in any case?

Obviously nobody wants adult material to be available to minors, but to me it seems like a lame excuse for suppressing minorities and selling us this homogenized, sterile, castrated version of culture, which has been sold to us as the mainstream norm. I just don’t buy that. A lot of people I know don’t buy that. When I did that story with Tom of Finland store, it was basically my artistic response to this situation and the fact that we do need to talk about it and we do need to resist this whole––the way I see it––huge, evil corporate machine that is controlling not just our personal data and selling it to the highest bidders, but also controlling the content. Yet they’re feeding on the very content that they’re trying to censor and control. I find it very hypocritical and immoral on so many accounts.

What do you see as the result of this kind of censorship?

The result of this censorship is that we’re being sold this very distorted and castrated version of the world and culture that is far from freedom of expression. It’s not what this country is about. I feel like we’re entering this really gray area where we have less and less control over the content we generate or the art that is being accepted in the institutionalized spaces. And I’m one of the lucky examples of artists who has had access to traditional gallery spaces, and I’ve been showing my work around the world for the last 20 years. But I’m aware of the fact that there are many queer artists and artists in general whose only outlet and platform is social media. So this puts them in a very difficult situation, because it essentially leads to not just censorship from the outside, but also self-censorship, because people are too scared to post anything that is outside of the norm being imposed on us by those corporations pretending to be social networks.

You’ve been dealing with this similar theme for much of your art career and it seems that in the beginning, like you said, the work took place in a more physical space. And now it’s shifted into the internet landscape. So I’m curious how you’d compare your fight against censorship then to now.

It used to translate into my works being physically removed from certain projects and shows and publications; I know I was banned from many media outlets. The internet, I did embrace it as one of my preferred mediums and I had a curatorial project on Blogspot before they started censoring as well.

But that was then and this is now, and it actually just highlights the need for not just an alternative virtual space for the minorities and queer community in particular, but also the fact that we can’t solely rely on the virtual representation or virtual exposure, because it’s become more and more difficult to be free of censorship. I feel like the future is in alternative spaces and platforms, not just online but in real life.

How does sharing work in real life compare to sharing online?

As much as the internet offers this great exposure for the new generation of creatives, I also feel like the limitations are greater than the exposure they get. It’s an ambiguous situation when you see self-censorship being one of the main driving forces behind what you see online on platforms like Instagram. They will support accounts that post endless selfies and topless pictures from the gym as opposed to queer artists who are doing something meaningful and radical and unconventional. Essentially the whole system creates mediocrity and reduces content to selfies and what people ate for breakfast. It’s a mediocre selection that is allowed and anything outside the norm is being censored.

I’ve been routinely censored on both Facebook and Instagram and sometimes pictures with no nudity are taken down. Clearly the system allows more freedom for trolls and homophobes and bigots than people who actually create something original and radical and unconventional.

When you’re creating work, do you have these things in mind?

To be honest with you, I never consider my audience and I never consider the outlet it’s going to be published in, because I think it’s counterproductive and not very stimulating in a creative sense. If anything, I was always making work that was against the grain and if something is being censored, it just gives me even more reason to continue with the work I’m doing. In a way it’s reverse-psychology validation for me, because I feel if my work is still considered so radical and dangerous, then I’m doing something right. I really feel this way.

And I never create images to fit the criteria being sold to us as “community guidelines” because I feel like I am the community and the people I represent. People who censor artists like myself are parasites, and they would be out of jobs if there was no content for them to censor. It’s a very distorted model and that’s why I say it’s not sustainable.

You have a different experience of censorship than, for example, most people who were brought up in the United States would have. Do you think people take it as seriously as you do?

Of course there are people who are narrow-minded enough and don’t know any better, and they would subscribe to this model and be happily censored for the rest of their lives. Some people are conformists. It’s not a surprise. But from my personal perspective, it’s not just a personal issue it’s also political, and it’s a fight worth fighting because it’s a part of a larger cultural context that we now live in. If we give up this freedom to post uncensored content, we might as well give up the rest of our freedoms. I don’t see how this online censorship goes with the fundamental principles of the American constitution; and being an American citizen and paying my dues to become one, I feel like I have a right to criticize the injustices and evil the same way I have the right to criticize Russia.

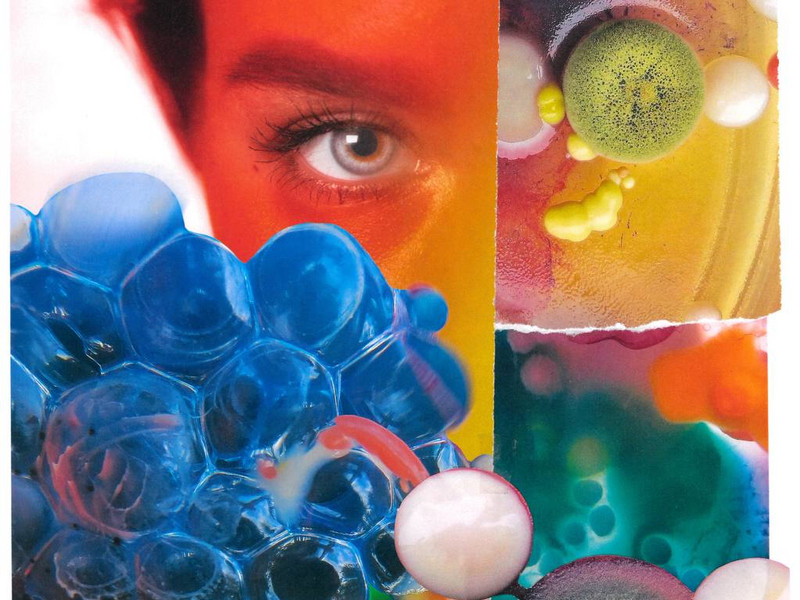

See more from Slava here.