American Apparel, Dov Charney and Me

I didn’t care. Any thongs that I’d accumulated by then would be replaced with boxers during college. I wasn’t into fashion and the fun-loving, hypersexual atmosphere American Apparel hawked wasn’t reflective of my early experiences of sex.

At 18, the sex I was having was never for pleasure, sometimes for money, and always for power. Most of my partners and all of my early clients were men significantly older than me. I played up my youthfulness by marketing myself via a very specific, barely-legal archetype, one that I found socially and fiscally remunerative.

I started crashing with this guy who worked at a Wall Street hedge fund any time I’d return to New York on college break. What began as me renting his spare room on Airbnb turned into a mutually beneficial relationship: the guy — let’s call him Joey — was closeted and wanted to have a girl on his arm to take to parties. While unspoken, the transaction was clear: Joey got a platonic escort and I got a free place to stay.

One of Joey’s friends gave me her expired ID so I could get into clubs and bars with them. On nights out, I would dress in full femme drag: an old pair of American Apparel jelly heels and spaghetti strap dresses. Joey’s male friends started calling him my ‘uncle.’ I could tell that most of them wanted to sleep with me (a few of them did) but also that my presence as a much-younger addition to the social mix made them uneasy. Seeing them squirm with discomfort turned me on and felt like role play.

This era at Joey’s felt healing, somehow. I was able to capitalize on the power of youth after being bogged down by depression, discomfort and uncertainty during my actual underage years. At college, I was living more ‘authentically’ when it came to gender and sexuality, and then could enact some lighthearted femme role play back in New York.

After college, I got into the writing scene in the city, going to readings at KGB and hosting my own at Honey’s in Brooklyn. I wrote quickie, a collection of short poems and early iPhone photography. The book took me to Los Angeles on a promo tour in 2022. I vaguely considered a limited-run merchandise line, maybe manufactured at the Los Angeles Apparel factory. But mostly I wanted to meet Dov. Or, rather, I thought that Dov would want to meet me.

I sent an out-of-the-blue Instagram Direct Message to Dov and invited myself to the factory. Within an hour, I was in South-Central Los Angeles, pulling into a massive compound of industrial buildings. I was 24, wearing a tiny button-up romper with my hair in braids. A middle-aged man in sweats and an oversized white T-shirt came out to greet me.

He gave me a brief tour of the massive space, talking to everyone he passed and never slowing down. At a sewing station, he opened up the Shazam app on his phone to figure out what song was playing.

“What is this? It’d be great for TikTok!” he exclaimed and kept walking while tapping into his phone. I followed behind him into an office area, towards a door that read DOV CHARNEY. I sat down confidently in the seat facing his desk.

A little brown mutt trotted in, tail wagging.

“That’s Barbara,” he said, with affection.

I scooped her into my lap. She licked my face. I felt Dov watching me.

“So, what can I do for you?” he asked with a raised eyebrow.

I looked around at the twin mattress on the floor in the corner. The framed photo of Bill Clinton at a deposition in the Paula Jones case. The Bill Cosby book on the shelf. The walls covered with printouts from his various legal cases.

What immediately came to mind as a response was, “what wouldn’t you do for me?”

This isn’t an article about Dov Charney. The influential individual — whether it be Dov, or Elon, or Ye — is primarily of interest to me symbolically. They serve an opportunity to work discursively, in order to investigate the following question, among others: how do we reckon with complicated figures, especially those who add to the realm of cultural production while at the same time perpetuating harm in and around those sites of production?

Through American Apparel and his current facsimile of a company, Los Angeles Apparel, Dov has entrenched certain forms of femme hypersexuality as the normative expression of both age, race and gender, as accessed through commerce; Dov the individual, on the other hand, symbolizes a certain kind of Ur-Masculine who is unrepentantly tethered to an unbridled id.

"Sleeping with people you work with is unavoidable!" he told reporter Hadley Freeman of the Guardian in 2017. Indeed, Dov’s initial splash in the press was related to his flippant and unapologetic stance on workplace dynamics; he made what seemed like intentionally inflammatory statements about sleeping with his employees. Sexual harassment in the workplace and even sexual assault allegations soon followed, all of which settled out of court.

As someone who has slept with people I’ve worked with in most of the jobs I had, I never really cared about any of Dov’s workplace-related statements. Sure, I was mostly sleeping with restaurant coworkers who worked similar roles as me. Dov’s ability to hire and fire, sponsor visas and the like changed the balance of power. But as I took on other roles — like working on film sets or at a tech startup — I too wanted to sleep with my much-older bosses, because of that very power imbalance. And sometimes I did, for no other reason than to take the taboo to its logical conclusion and see what lay on the other side.

When it comes to the sexual assault allegations against Dov, I find myself returning to the aforementioned question: how do we talk about hard things? How do we keep someone in the cultural fold who is an industry innovator (which Dov arguably is), who might become even more ideologically radicalized if he’s completely ‘canceled,’ who has created numerous jobs with fair wages and health benefits for undocumented immigrants, yet who has still not holistically acknowledged any harms he might have caused within the workplace with regards to sexual assault and harassment?

In the ensuing years since our initial meeting, I did some paralegal work for Los Angeles Apparel. I wrote some copy for the website. A bunch of small things added up to what I’d call a strange but genuine affection for one another.

Later in 2022, I was on a call with Dov and a former investor in American Apparel, who would go on to hire me to write for him. Dov was making the introduction, and at one point he said, “I’ve been dating 20 year olds for 20 years now, and this is the best batch of them yet.”

I remember thinking: what he’s saying is that he thinks I’m smart. And even though we aren’t dating and never have, he’s saying he values the disposition of ‘being smart’ in combination with ‘being young.’

After I hung up the FaceTime, I felt a sense of foreboding. I took a deep breath and recognized a feeling of… jealousy? I couldn’t figure it out. I wasn’t always going to be young, so the anxiety was clear: this market asset would depreciate in value until an inevitable and prolonged period of cultural obsolescence. But my jealousy was harder to explain.

I’ll arrive at jealousy by way of Emily.

Emily. My first girlfriend.

I used to cancel plans on Emily last minute all the time. I was vague with my emotions and made sure she always came over to my place, as I never once made the effort to stay at hers. I was the epitome of a flaky fuck-boy, keeping the upper hand through half-truths, missed calls and just enough attention to keep stringing her along.

One day, Emily sent me a series of texts expressing concern and confusion about my shitty behavior. She ended the text thread with: “Anyway, I really care about you and would love to spend some quality time together sometime this weekend if you’re around. LMK.”

I texted back “Hmm ya, sounds chill. Could work.”

I felt sick with this power I had over Emily… sick with power.

Eventually, I just felt sick.

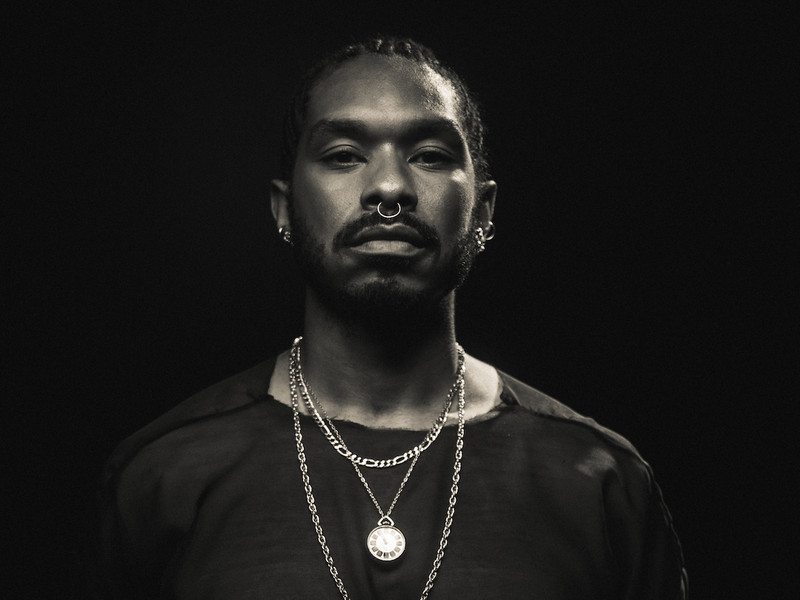

Photo by Taryn Segal

Years later, I got fitted for my first suit after being invited to my friends Grace and Zoe’s wedding last spring. I dropped over a grand in cash at Brooks Brothers, being catered to by an employee there who kept asking if I wanted the pants tailored in a more feminine way.

My photographer friend Taryn Segal came to document the fitting. I sent a photo to Dov, who responded back, “Young Dov.” I felt elated.

There’s the jealousy.

Do I want to be Dov? I honestly don’t know. I think age gaps are sexy. I think power trips are sexy. What I’m reckoning with now is a (perceived or real) impending loss of power, and a slow recognition that I might not be interested in either side of the dynamic anymore.

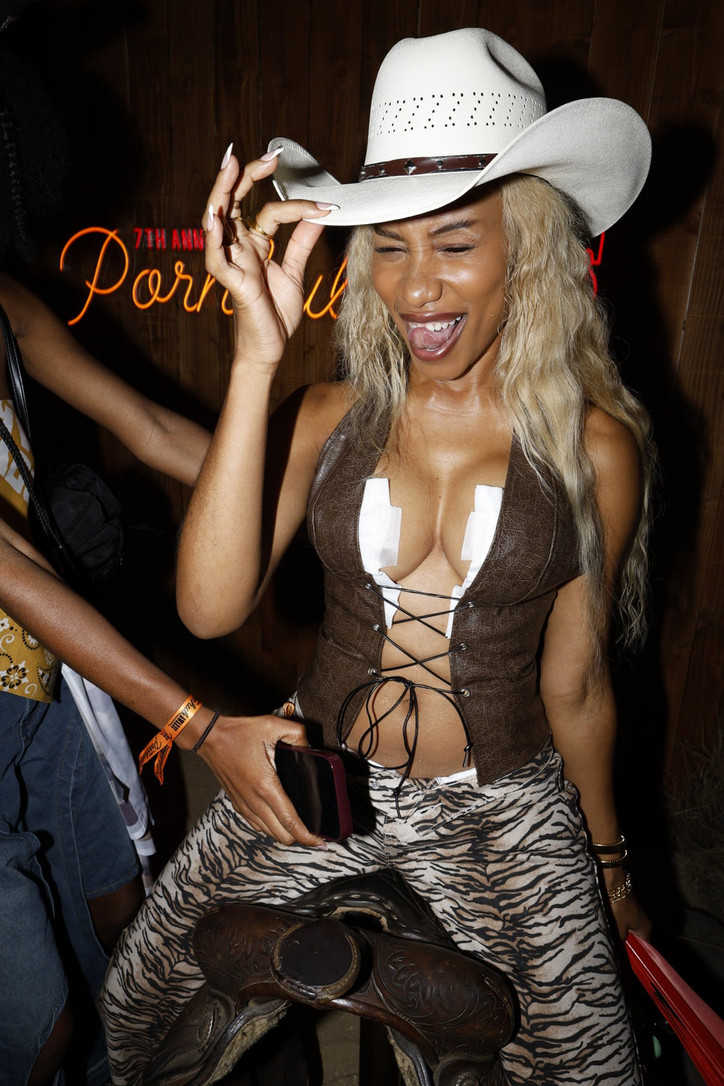

It’s the end of 2023 and I’m riding in Dov’s old school Toyota Camry (“These are great, so old school, I bought two of them”). We’re driving west to Brentwood, for a meeting with Ben Kohn, the CEO of Playboy. There's a potential for all of us to work together, and we’re meeting for the first time to discuss it. The previous night, Dov and I spent two hours on FaceTime (Dov from his room at the factory and me from a room in his Silver Lake mansion) to talk it over.

In Brentwood, Ben orders a stack of pancakes and talks about Playboy’s current “capital light” model. Dov and Ben dive into financial specifics for the majority of the first half hour. I chime in here and there, essentially asserting that whatever they spend hosting at Tao in Vegas, for example, could be cut in half and reinvested in underground, invite-only parties with relevant DJs and better locations. And a quarterly zine couldn’t hurt, either.

About 45 minutes into the meeting, Ben gets up to go to the bathroom. Dov turns to me and says, “You’re talking too much.”

I keep going back to the original question. What can I do for you?

Ever since that meeting, Dov feels like a meal eaten right before getting food poisoning. I delighted in the meal and now I delight in it being out of my system.

Maybe what I learned from American Apparel was a lesson in body autonomy that has nothing to do with clothes. Dov is just another piece in a greater praxis of self-discovery. The pattern of aligning myself with powerful men and then feeling enthralled by games of mutual exploitation has served me, and I’ve relished in the years that it’s worked. I’ve taken knocks in the scarier moments when it hasn’t. I’m finally ready to be on neither side of the paradigm.