‘CIÓN, MAMI – An Editorial Escape to the Heavens

The film embodies oasis, with each aspect driven by the ingenuity of trans creatives. In partnership with SYRO, a queer trans brand lead by Shaobo Han and Henry Bae and executive produced by the Black Trans Femmes in the Arts Collective founded by Jordyn Jay, the editorial captures the essence of trans expression and communion.

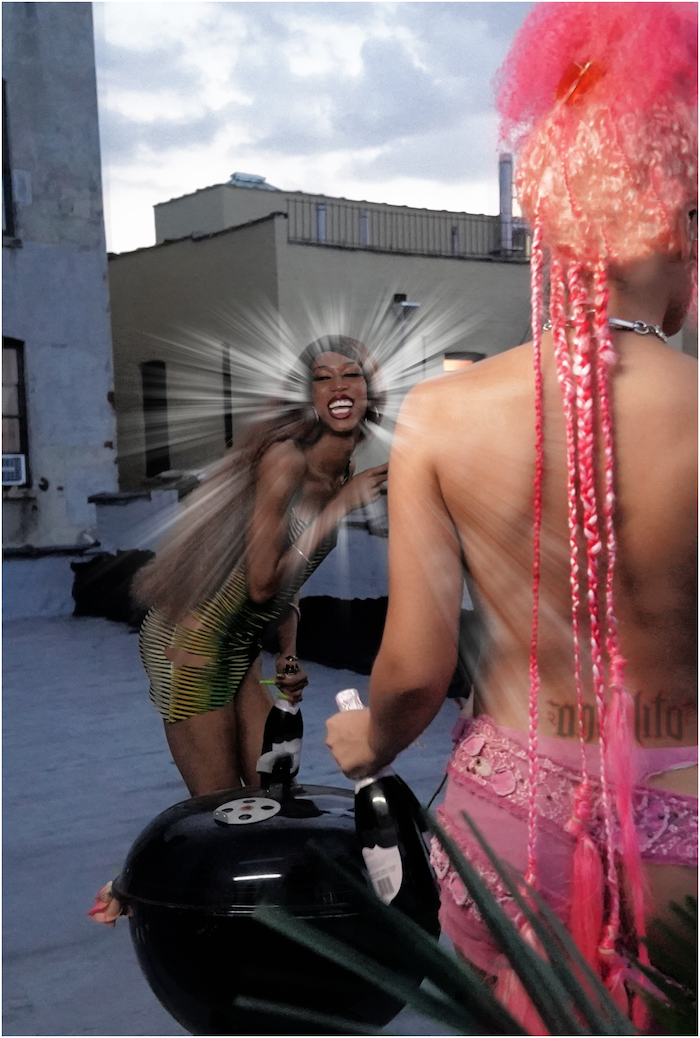

Ending on a roof as the sun sets and turns the sweat of the day to glitter, the Angelito Dolls assemble. Exchanging kisses (one on each cheek) and moments of intimacy and joy, the sun sets on a hectic city, and the night sky embraces the Angels enraptured in a piece of heaven.

CONNOR GAREL — I think the best place for us to start is at the beginning, with the genesis of the film. How did the idea come together? And when did the form it might take become clear?

KAM KORDERZ — I remember it was early last year, and Angel had reached out to me about this project they were talking with Syro about. It was a loose concept for a fashion video, but not necessarily a film yet. It was based on this one episode of Sex and the City [S3, E18] that was basically focusing on trans women being gentrified out of their neighborhoods in New York City. From there it got bigger and more expansive. I was only supposed to model in it, but then I was like, I really want to direct this and make something from our points of view as trans women and as dolls. And it blew up into this whole production of a film. That’s when we reached out to BTFA (Black Trans Femme in the Arts) and got funding, and I started writing it as a screenplay instead of just a video. The relationship that we were building with each other over the last year is kind of what informed this, as well as this idea of taking up space anywhere we want in New York City without feeling limited by what neighborhood we’re in or who might be around.

ANGEL ANDRES — Initially I wanted to highlight what a New York City summer feels like, especially when you’re on a rooftop. And that led me to think about the Sex and the City episode, where at the end it’s all of the girls on a roof with the trans women, coming together after the conflict they had earlier in the episode [when Samantha throws a bucket of water at them]. We started to just throw ideas around, and Jordan [Kam] had written something that was based on some of the experiences we were all having throughout the summer. We really wanted to highlight that connectivity and that family feeling, how we would often come to each other’s houses and eat together and just spend time in community with each other. I think about how music is often written to describe a moment or a feeling, and I feel like this film is similar to that. It’s highlighting a feeling or moment in time for us. It’s a description of how we come together and empower each other.

CG — This is a fashion film, first and foremost, and so fashion and self-presentation are really important elements for its visual language. There’s nothing casual or understated about the hair, or the makeup, or the nails, or the clothes anyone’s wearing. Everything has this otherworldly tone. Demi’s top isn’t even a top—it’s hair improvised into a “garment.” How did you figure out the style direction?

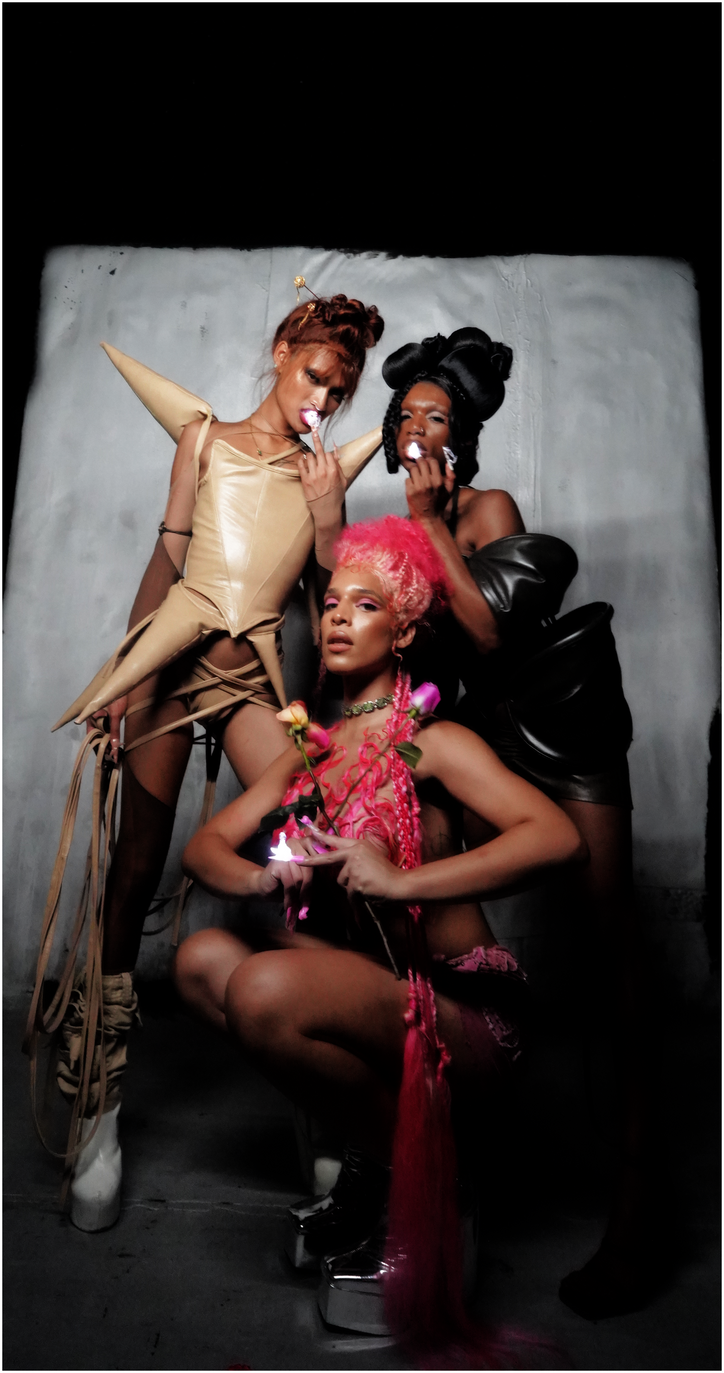

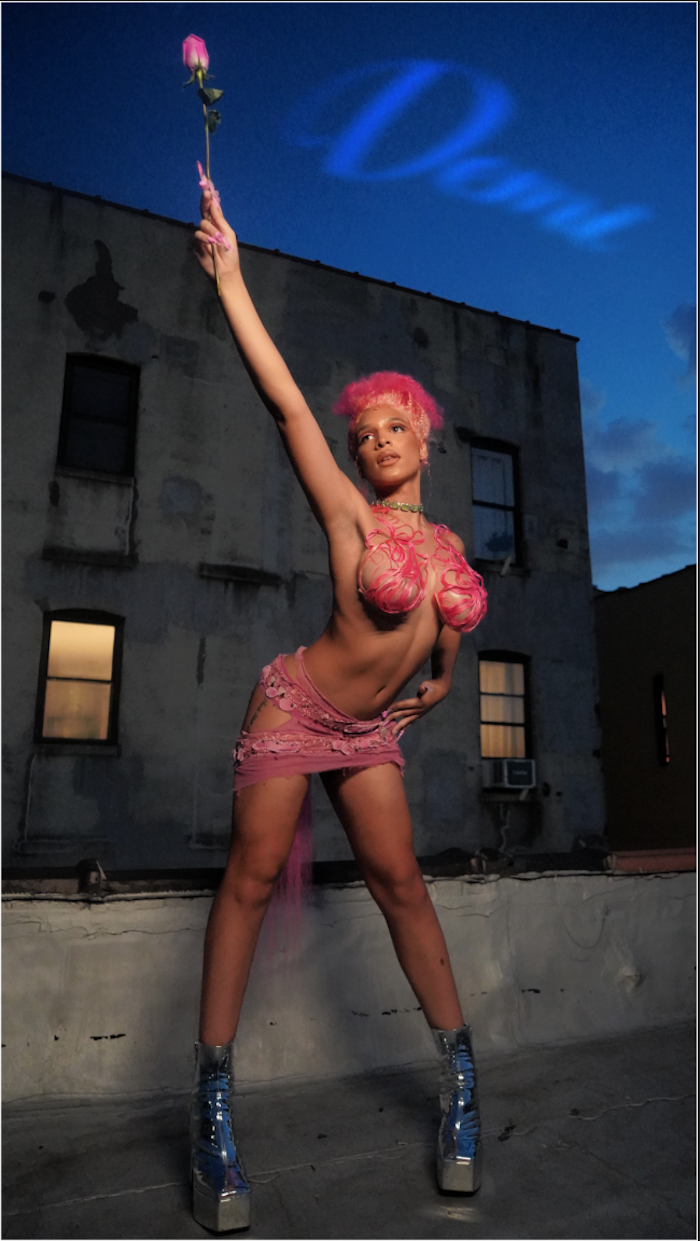

AA — We knew the element of fantasy was really important, so I spent a lot of time looking at images that had larger-than-life moments. We spent a lot of time looking at that Nicki Minaj commercial for the Pink Friday fragrance, where she’s a giant in New York City. We were trying to figure out ways we could make this larger-than-life without necessarily having to be scaled bigger in a room. So you have Demi with the hair around her chest, and that’s an element of fantasy. You have Jordan wearing silhouettes that distort her natural figure, and it’s the same for Sinn’s look. It’s a wardrobe that takes up space in a room. So I was looking at images and then telling Sinn, like, this is what I’m thinking.

SINN CHHIN — We always say that we’re not from this world, and that we’ve just been placed on Earth to take up space and do what we came here to do. And while looking at the film, I realized we do actually mimic a few creatures. Demi with her wave top situation and that skirt is giving jellyfish-y. My look is very prehistoric, and it’s giving dinosaur. It’s like we’ve already been in this space, but we’re going to come back and bring new shit to the table. When I was making the clothes, I was trying to embody us in a piece of clothing. And I think that’s what made everyone feel the most powerful.

DEMIYAH PÉREZ — Sinn literally, with her hands, sewed everything we wore. So for my own curiosity I just want to hear her reflect on that process.

SC — For my look, I was working very close with Ranxelle Soria [Roxy], who also helped style the video, and I knew that I wanted my look to be a dinosaur that was kind of shedding its skin. It’s like we crash landed here and we have to shed our skin to be exposed to the atmosphere. So I had Roxy do this thing they call second skin, which is a method of layering pantyhose. And then with Jordan’s look, your eye doesn’t really know where to go. You’re fascinated by the shape. It keeps the eye dancing. And with Demi, as a person she has this Mother Nature kind of thing to her, so the hair makes everything more organic. It’s like her hair knows that her body needs to be covered for protection. It’s like that Kelela video for Blue Light, where her hair is growing around her body. That’s the direction we went into.

CG — Why is style important to each of you? What does style help you to achieve?

DP — In the period of time that we were developing this, and experiencing sisterhood with each other, we were spending a lot of time in each other’s spaces, sharing clothes.

SC — Girl, we still sharing clothes!

DP — And so our style in the way is like our energies colliding. Whenever each of us wears something, we all bring a life to it, and we’re able to make it look like something brand new. Sharing clothes is like sharing resources, and that’s the basis of all the values that we have of equity and alignment and harmony as a group.

AA — We don’t let the clothes wear us. We put them on and embody a character. I was telling the girls for the film, “Y’all are all celestials from different universes and you’re coming together to gather after many years, and y’all are preparing for this fabulous dinner.” And so that’s why they were all wearing high, tall hair, to shape the face and feel like a crown.

KK — I looked at Demi’s character as the maven and the matriarch of our household in a sense, the one that grounded us, and that’s why it was really important to have her voice carry us through the film. And then Sinn and I bring certain elements that complete the household. But as far as my personal style and fashion and beauty, that’s been what has transformed me and what’s been the vehicle into my transition. And I think art is the best way to express that.

CG — I want to talk about the cinematography for a moment, which is sort of dreamy and magical and atmospheric. Angel, you mentioned this otherworldliness as an element you wanted to bring into the film. And there’s a softness, too—an intimacy. Could you speak a little bit more to the creative and art direction of the film and what you were hoping to do with it?

AA — A lot of the inspiration for our initial ideas actually came from some drawings that Jordan had made. That’s where we came up with the royal fantasy vibes. But the entire walkthrough of the film is deeply connected to our experiences today, spending time together, sharing dinners, being in community. I think it’s really beautiful how we were able to create a fantasy out of something that’s really real to us.

KK — Those drawings that I did formed one of the initial concepts we had for the film, which was this extremely experimental, hyperreal thing that was even more fantasy than it is now. But through our process talking with one another we arrived at something that felt more grounded in how we live but that was still fantastical. My style as a director and cinematographer has always been inspired by Wong Kar-wai films, where it’s very dreamlike and centered in these big cities. And then when you see the city in person, it almost doesn’t feel real. I also wanted to bring into the film certain elements that we share in our intimacy together, like how it’s always a double cheek kiss when we greet. And when we’re around each other, there are sounds you hear: our nails clacking, our heels kitting the floor, the sound of a kiss on both cheeks. There’s so much sensory to the way we interact that’s uniquely us, and I think it narrates our sisterhood in a way that words can’t. So I really wanted to hone in on those moments with the wide angle lenses and create that fantasy with things feeling larger than life, but also something that people still find is familiar.

CG — I love that you talk about Wong Kar-wai, because one of the central themes in his work is this sort of urban loneliness, these love-sick characters drifting about in cities they feel alienated by. But what I love about this film that you made is that we don’t feel that loneliness at all, because it’s invested in togetherness and in community. And it’s interesting, because the video is filmed in Harlem, which was a black cultural mecca in the 1920s and 30s—a period referred to as the Harlem Renaissance, when there was an artistic rebirth. Some of you live there, or have lived there in the past. Can you talk about the significance of Harlem to the film?

KK — I think Angel, as a native New Yorker, you should talk about this first…

AA — Harlem was deeply connected to our ideation process, because we were looking at the way we move through space and what that might make other people feel. We were considering recreating all the chatter we overhear when we go out, because we can’t help but to disrupt a room when we walk around. One thing that always happens is the staring. But we decided that that isn’t important to us. It’s not what makes us. When we wake up in the morning, we choose ourselves, and the people who stare and talk don’t know who they are, so they can’t choose themselves. We ended up in a mode that really empowers and hopefully inspires other people to fully embody themselves.

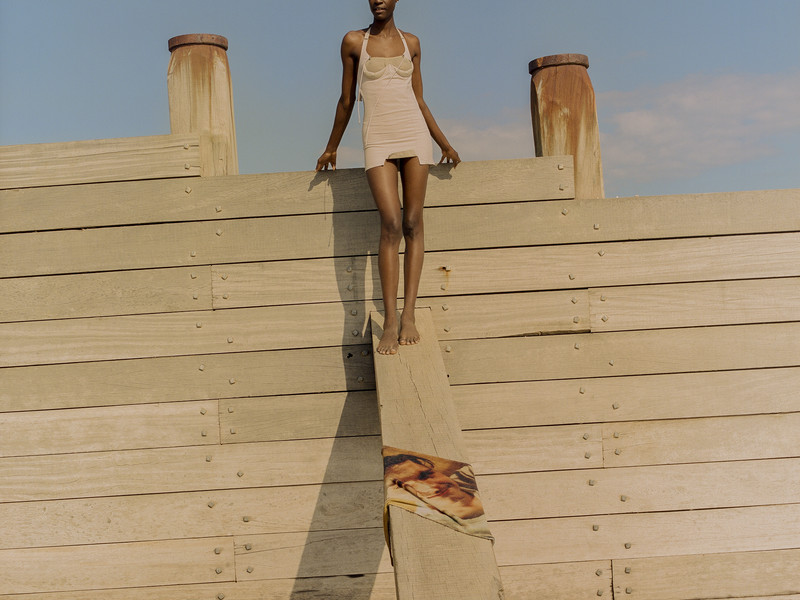

KK — For me, not being someone from New York City, the Harlem Renaissance and the neighborhood of Harlem have always been very influential. I’ve worked in ballroom spaces and jazz spaces and a lot of places uptown that are still to this day very evocative of the culture, especially of trans and queer people. Where we shot, in Angel’s neighborhood, is such an interesting intersection, because Central Park is right there. We see Sinn in Central Park in the film, which is a big symbol of gentrification and the whiteness in New York City. But you go a little bit north, right there to that corner we filmed at, and it’s this center of blackness and Latin American people. So it’s a juxtaposition on one street corner that’s representative of the space we take up constantly in life.

CG — When you were thinking through the film's narrative and the story you wanted to tell, what was the first scene that came to you?

AA — I think it was the liquor store. We went from thinking about possibly designing an entire space where they would be huge to figuring out how we could make it fantasy without the excessiveness or the craziness of having to do all that. Like, how do we simplify? We thought about possibly going into the liquor store with the clicking of the nails and Jordan’s outfit possibly moving through the room and touching the bottles. That was really exciting for me. That was the first time I started to see everything unfold. Because then, we thought about Sinn and Srey Sral at the park…

SC — I remember them talking about having Srey in it, and then I created an outfit where my corset lacing was part of her leash, and I think, for me, that was when I was like, “Okay, I’ve never felt more like myself.” And then seeing us all together, the idea of us walking onto the roof—it reminds me of us getting into an Uber to go to Nowadays, like, “Oh, bitch, we late!” It feels like a vlog. When we were writing everything out and had a straight story to tell, we realized this is practically what we do every day.

CG — I want to talk about sisterhood, because there’s this felt and resonant warmth to the film that I think is a testament to your bonds. The joy feels genuine, not acted. Can you maybe talk about friendship and sisterhood and the role that plays in the film and your lives?

KK — I feel like we really came together in a work environment. The first time I met all of them was through the first film that we worked on together, Toxic. It became an organic sisterhood that has informed a lot of my own identity in the last year, and it’s answered a lot of questions and framed things in a different way. Being here, I’m so far from my biological family. They’re all in California or various other parts of the country. And I’ve moved around my whole life. So I’ve never been in a community, or or had a big family that was around me. So to have this was very gratifying, and the film came out of it. It was this stream of consciousness thing that never really ended until now that we’re done with the film, because we just kept pouring what we were experiencing into the film and it had its own life.

AA — I think what brought us together was our creativity, but what holds us together is our connectivity. We hold each other accountable, and we choose to be patient with each other, which is something a lot of us didn’t have growing up. But we recognize that the power we hold in our unity is something we want to harness and protect. So I’m grateful to have them on my team, not only to write history but to always empower me and encourage me to be a better person.

DP — I think our sisterhood really informed a lot of my healing. I learn so much about myself by having me reflected back in the girls all the time, and our sisterhood gave me access to parts of myself that I’ve looked over or resisted. It’s a space of love and safety. And if you’re lucky enough in a lifetime to come into your tribe and hold space for each other, that’s really special. We’ve fought for so many years to get to a place of being free, and all of our moments together are a celebration of that triumph and of getting to the point where we get to choose how we want to live. I moved around a lot as a child, and I was always adapting. I was never grounded in one space. So to have a strong group of friends helping each other and growing together, waking up determined to uplift each other—I think it’s really beautiful.

CG — Can I ask about the music?

KK — I wish I would’ve asked Skyler [Hawkins] to participate in this, because the way they’re inclined with music is so interesting, and the references that they have and the way they take in information and can create something that you wouldn’t expect is so wild. We’ve been best friends since I was a teenager, but we’ve been working together and they’ve been scoring films I’ve done for years now. We all recognized their ability to produce something that would match the tone of the film, and that spoke to the community that we’ve built and everyone’s desire to help us come closer to fulfilling whatever it is we’re creating. So as far as the structure of the music, I originally said I didn’t want to [mimic] ballroom. I didn’t want this to feel like a cookie-cutter thing, where we’re trans and we’re walking to a beat for runway. I initially said I wanted this to be nothing but trans women rappers. And then it took on a life of its own. We’ve spent a lot of time in the rave scene, and in spaces where they play house music, or where there’s EDM, and all these sounds that are very cinematic. So we had Suffy Baala make a really cool mix that Skyler then engineered into a score. I just wanted each of us to have our own sounds in our introductions into the film. And I wanted the climax, where we’re in community, to feel very sensory, and that lends itself so well to Demi’s voice.

CG — Demi, we hear your voice in the beginning of the film and at the end. At one point, you say “We can’t be destroyed” and I’ve been thinking about it since I watched the film the first time. Can you talk about what this narration offers and why it was important to include it?

DP — For the process of writing the narration, I started writing down what this film reflected for me. The “we can’t be destroyed” was an insert from the narration Jordan wrote in the first draft of the script. I began combining my voice which offered a matriarch soft tone alongside the empowered boldness of Jordan’s tone. I sat in silence and wrote various drafts of the final voiceover, then I recorded through my phone and Skyler was able to blend it in with the soundscape of the final cut.

KK — My process was very similar to Demi’s. I began writing out things that were coming to my head, kind of just personifying this idea of an endangered species and making it into a bold, dramatic, metaphorical way to describe these daily interactions and struggles of transess, as well as our own individuality. I knew immediately when I wrote it that I wanted it to be Demi’s voice because from the very first time I met Demi, her voice has just been a lullaby. It’s always so nurturing and she has this melodic safe tone to her speaking voice that informed her characterization in the film.

DP — Also reflecting back in the process, the first reference I had was Janet Mock’s voiceover in Blood Orange’s track Family. I remember hearing that track for the first time and feeling empowered by hearing a mature and enlightened trans woman speaking to me and consoling me. I felt like she was on the phone talking to me. So when I did the voiceover I wanted to embody my inner Janet. To be in the position of doing voice over has been a new outlet of expression I’ve looked forward to pursuing for a while. I’m honored that Jordan trusted and envisioned me to take this role on.