America the Beautiful

Hailing from rural Pennsylvania, Ziegler developed an admiration for distinct Americana style early on. His piece “Hooks” (2018) contains 100 different antique hat hooks, including duck heads, spindly tree-branch like hooks, and one of a perched bald eagle—visitors can even add their own hats or other treasured head adornments to the piece.

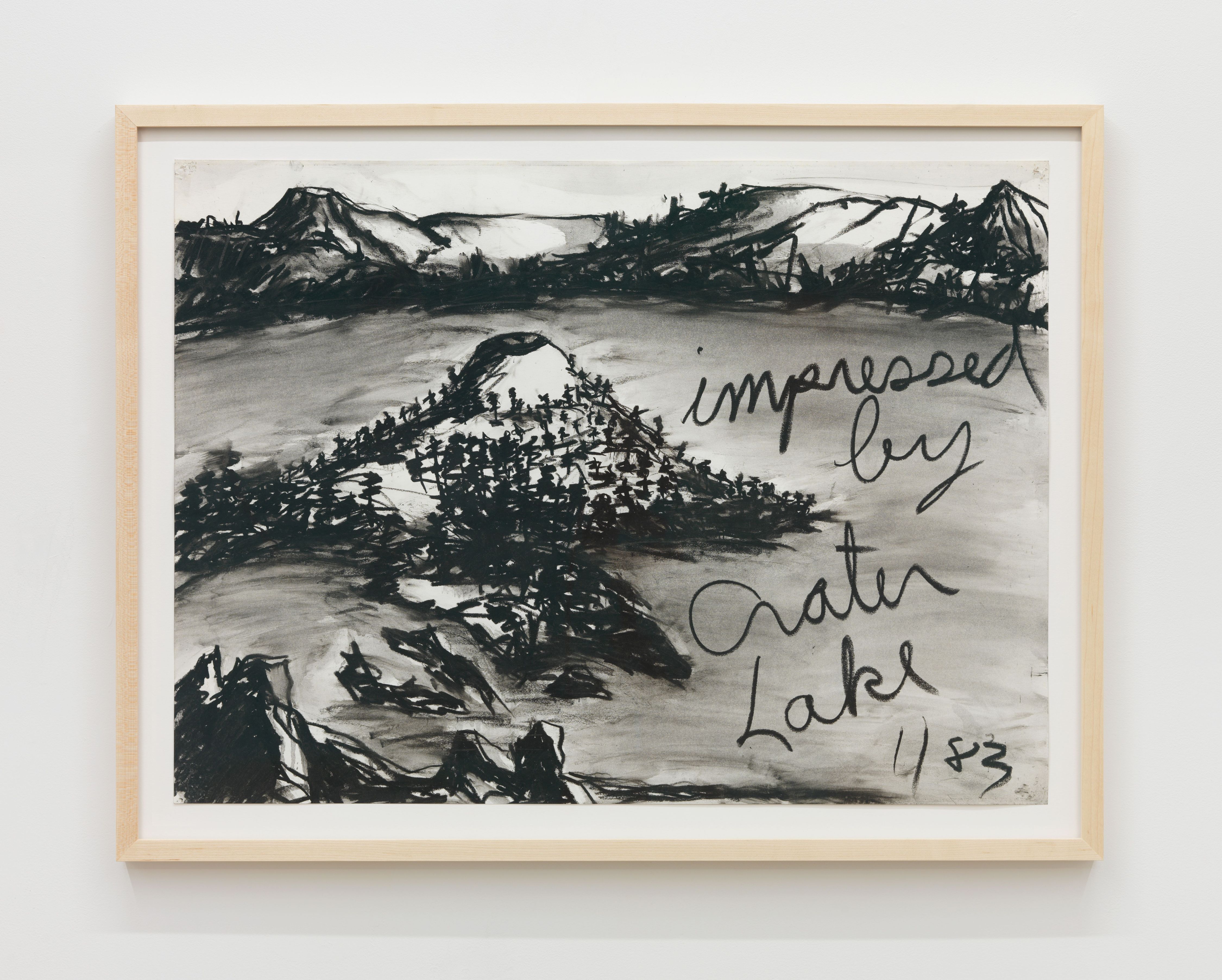

Despite his rustic roots, Ziegler does not shy away from poking fun at American values at large. For example, Ziegler and Ericson’s 1986 piece “From the Making of Mount Rushmore” contains stones that the artists took from the historic monument and displayed them to look like the four presidents—an act they later would admit to being one of “civil disobedience.”

office spoke with Ziegler about his current exhibition and upcoming projects. Read the interview below.

Tell me a bit about what you’re doing now with the Sandhills Institute.

I run an artist residency program in the Sandhills in Nebraska. That area is mostly sand and grass that’s used for cattle ranching and it has an incredible ecosystem. I had no real connection to this place, until I took a family trip to Mount Rushmore, Devil’s Tower and Badlands National Park. We drove through the Sandhills on our way back home and I just fell in love with it. So I bought a ranch out here about 13 miles from Rushville and my wife and I bought an old 1950s grocery store on Main Street in downtown Rushville that we’re making into an art gallery and cultural center.

I invite artists to the ranch and I teach them through professional workshops about the grasses, cattle ranching and grazing, as well as the history of the community. We have a dinner with the matriarchs in town and they tell us stories. We also have a community picnic and we’re beginning to work with the local high school and Chadron State College.

All of the projects are community-driven and involve some level of social engagement. So, I require the artists to make at least three visits here to do research and get to know the community here before they can propose a project. The institute’s been slow in the making because I require these three visits, but we’re beginning to get some proposals in place and we’ve now completed two major projects.

How do you make yourself a part of a community in order to create something that’s within and reflective of it without disrupting it?

That’s the key issue. I mean it’s not an easy thing to do and I don’t think all artists can do it. First of all, I like a lot of lead time if I’m being asked to do a project. I like to have a year and a half to two years to develop a project because, if I am involving community, it’s important that I get to know that community in the process.

I also try to develop projects that can engage the community and use the language that’s central to that place. So if I’m doing something with ranchers, for example, then I try to make the project about ranching. These are some of the things that I do to integrate into a community without disrupting it. But I also don’t mind a little bit of disruption. That’s what creates an interesting artwork. It’s good to raise questions and issues and expose things that don’t normally get exposed. But I’m invested in Rushville long-term, so the most important thing that I’ve learned here is that I have to gain trust so that people understand that I’m here to stay and I’m serious about what I’m doing. I’ve joined the chamber of commerce here, I get physically involved in things that happen.

The grocery store restoration project that I’m doing on Main Street’s huge, it’s important to the economics of Rushville. But I think it’s really a matter of getting to know people. I think that’s a really critical thing. That’s what I try to get the artists to think about.

Is that where the idea of artists making three visits to Rushville before proposing a project comes from?

Yeah, it’s really to get to know the community and do some serious research. I pay for the artists to come here and develop the idea, I provide housing and airfare. Then they get funding to develop their projects.

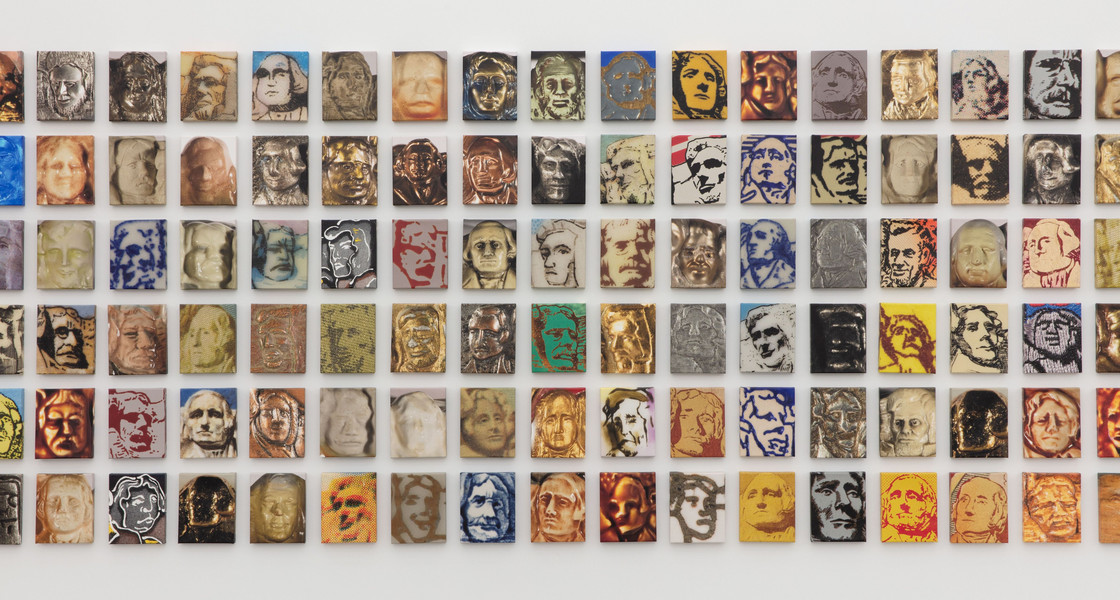

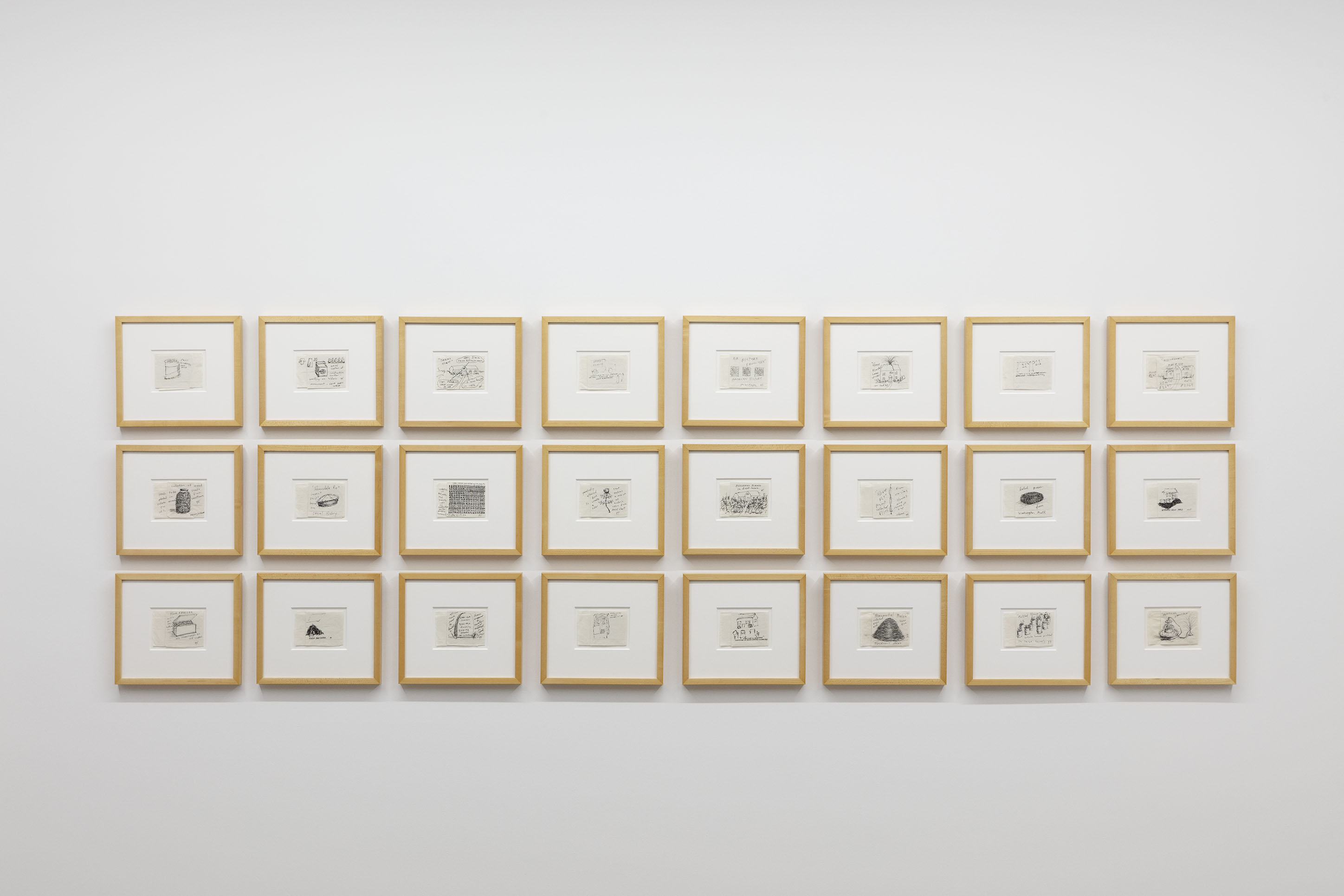

Regarding the Activated Artifacts exhibit, particularly the “1000 Portraits” piece, what is the significance of displaying it now?

Activated Artifacts is what I call a lot of my work because I tend to respond to things and somehow manipulate them or represent them. So I’ve been working on this series of projects that are made from collected items like the coat hangers but reactivating them in a way that involves social engagement or objects that have a social history to them.

Mount Rushmore might be considered a problematic monument because of all of the politics surrounding it and the fact that it exists on Native American land. There’s also all of this questionable history around the monument’s sculptor, Gutzon Borglum, and whether or not he was a member of the KKK. It was actually initially developed to be a tourist attraction, which it is. It brings over 2 million people to that region every year so it’s an economic force in the Rapid City area. I was very fascinated by all of that and I began collecting vintage Mount Rushmore souvenirs because each one also has its own history. I did that for about 10 or 15 years.

Late last year, I was invited to show a piece and participate in a conference at Cornell on the discussion around problematic monuments and what to do with them. So, I proposed this project in relationship to the conference and they provided some funds for me to produce it.

Regarding “Hooks,” how does location play into that piece? What do you think New York will add to it?

I’ve been asking people to put up something that is really hard for them to part with because it has a history to it—to me that adds the possibility of stories. Having lived in New York, I know the diversity and the uniqueness of individuals. I’m hoping that some interesting hats will end up as part of the piece. I think every time it gets shown it will have a different relationship to the community.

A lot of your work is about both celebrating and critiquing American values and practices, especially in rural America and the Midwest. How, if at all, has your perspective on the region changed over the years?

Well most of my work responds to a kind of iconography of American history and American icons so there’s always a built-in critique of what I’m trying to accomplish. For example, I created a piece with 50 American flags, one from each state. They were all torn and tattered flags that I collected from people in exchange for a new one. It was first shown at the Tang Teaching Museum in relationship to the 2016 election. I couldn’t have known that what happened was going to happen, but it was interesting to display it and talk about American values at a time when so much is in question and so many things are happening. I think the work has a built-in critique.

I’m not promoting any particular value system—it’s about questioning the value system. You can see the piece and be conservative or liberal and have issues and questions with it. I try not to be dogmatic about a particular point of view.

I’m curious about why you have always thought it was important to show work based outside of New York and L.A. art spaces?

Well, I grew up on a dairy farm so my background and my relationship to the world is probably different from a lot of other peoples’. I grew up in rural America and eventually found myself in the middle of the New York art world. I think there are a lot of important, good things that come out of it, but I also feel at times that it’s extremely insular, that it speaks to itself. In that way it doesn’t interest me as much. And I feel like I respond more to Rushville, Nebraska than I do to New York City at this point in my life.

There’s also an idea in America that the big cities on the East and West Coast have one way of thinking while the middle of America has another ideology. I think there needs to be more of mixing of viewpoints. I would love to promote the idea of more artists coming to rural America and working, not to change minds, just to have more openness and more willingness to have discussions about things. It’s not easy for some artists. I had one artist say that they didn’t want to come back to the Midwest after Trump was elected. And that really upset me because that’s the wrong attitude to have. You should want to come back here and have an engagement and a dialogue. People here are smart, educated and they have their own ideology about things. And there’s nothing wrong with that.

I consider the Sandhills Institute an extension of my work. I think I’m doing something really important here. Right now, my energy, my time and my ideas are really focused on rural America and Rushville, Nebraska. But it’s important to me to keep that dialogue and sophisticated discussion about the art world going.

Activated Artifacts will be on display at the Perrotin Gallery until August 16.