Amie Dicke’s Open Arms

For her solo exhibition Open Arms at Anat Ebgi Gallery, which opened on Friday September 6, Dicke debuted a new body of works that continues her exploration of the signs and symbols shaping how we view the female form. In Open Arms, she expands her focus to include men’s fashion ads, art catalogs, and art history books. What connects these different interventions into modern masterpieces and male model photoshoots is a defiance of the convention that reduces women to passive objects of desire within images. At the same time, Dicke embraces the human tendency to project desires onto these images, making her revisions both sensual and fluid. Open Arms can be seen as a love letter to the art of self-representation, while critically examining what it means to engage with these representations.

Hi Amie. I’m really excited for your show at Anat Ebgi Gallery. I want to start by asking about how you first came into the art world. You were a model in New York in the early 2000s, right?

This story has become a thing of its own. I did live in New York for a year and a half as a starting artist to follow my then fresh love, but I did not model. I only worked as a teen model in Rotterdam. I was too shy to be a good model. The camera made me feel very vulnerable. I love fashion. Still, I prefer to stay on the other side of the camera. In Rotterdam, I also made sculptures and got some attention fresh out of art school. Somehow, making sculptures did not feel viable because of how masculinist it is in Europe. Instead, in New York, I found myself through all the imagery I saw on the street advertisements and magazines. Everything felt insanely new for me. I even learned how to navigate the subway because of these huge Calvin Klein posters. So, I started drawing on them and cutting them away.

What made you particularly attracted to images of young women found in fashion advertisements and magazines?

I am fascinated by how images of thin, young women are constantly pushed onto us. They often link back to archetypes like the muse or the Holy Virgin. I was studying old portraits of Mary and realized how her posture or gaze can reveal esoteric meanings. The same thing can be said about the innocent young girls I see in fashion imagery.

And you mostly construct images of faceless women in elaborated contexts, be it clothing or setting, which can be quite telling. I am curious as to why you are not fully denying our access to these women’s psychology.

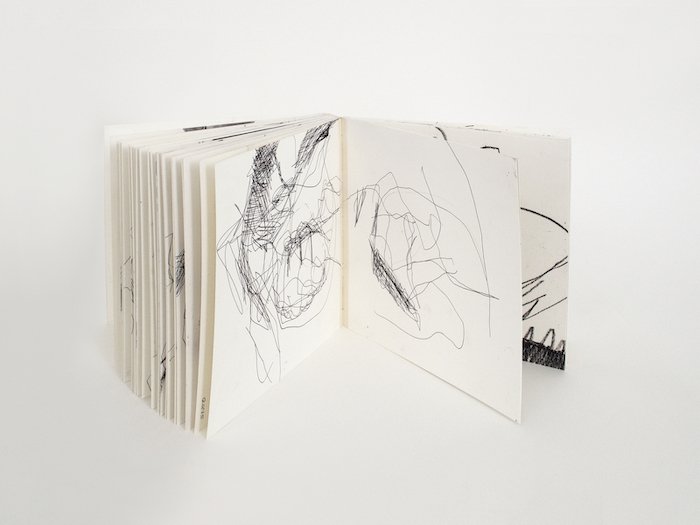

My working process is full of discoveries. I rip pages out of magazines or art books, scan them and blow them up, and reproduce them on archival paper. Throughout the process, the images speak back to me, hinting at what to leave untouched and what to scrape away. In all cases, the images end up having this dualistic quality, somewhere between absence and presence. The women in my works reject the viewer's desire to identify with them but at the same time demands more attention. I find this doubling gesture very alluring, as if they took on the eternal quality of historical portrait painting.

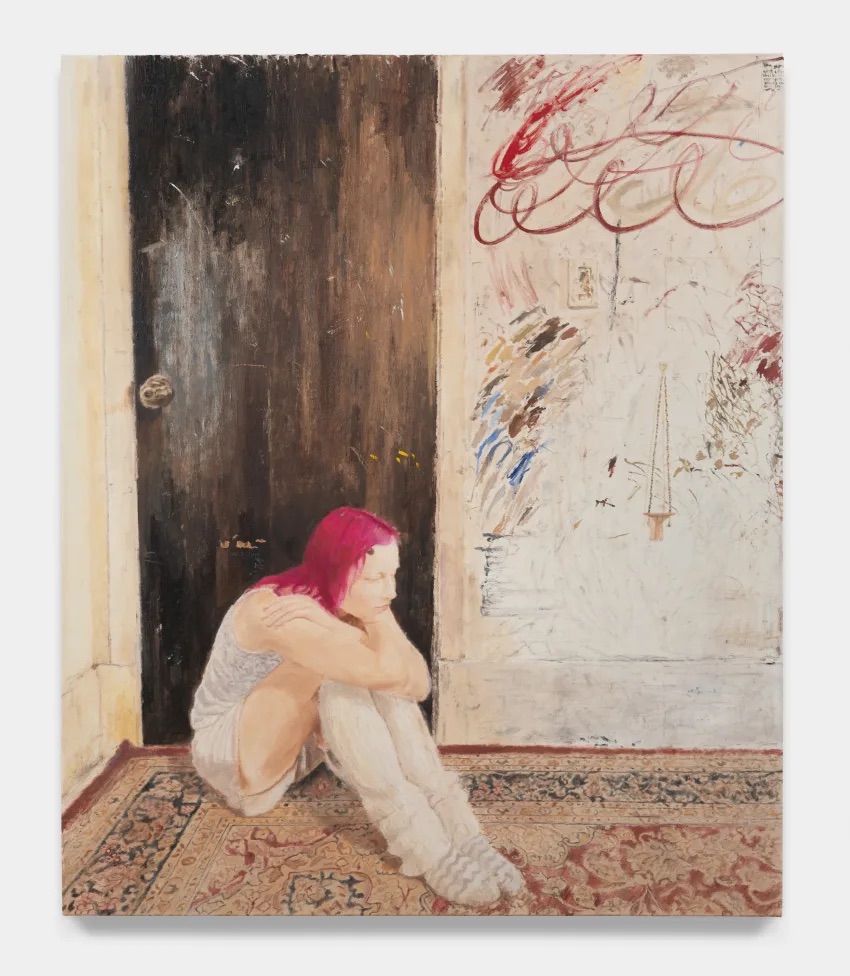

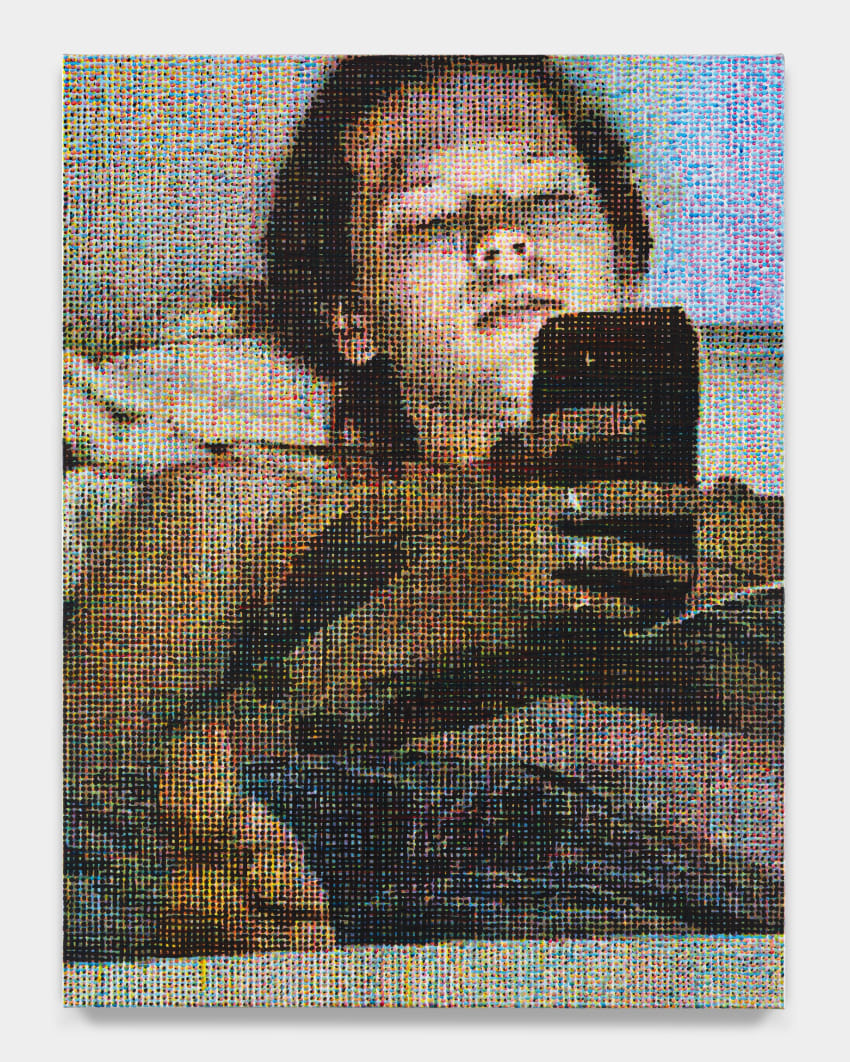

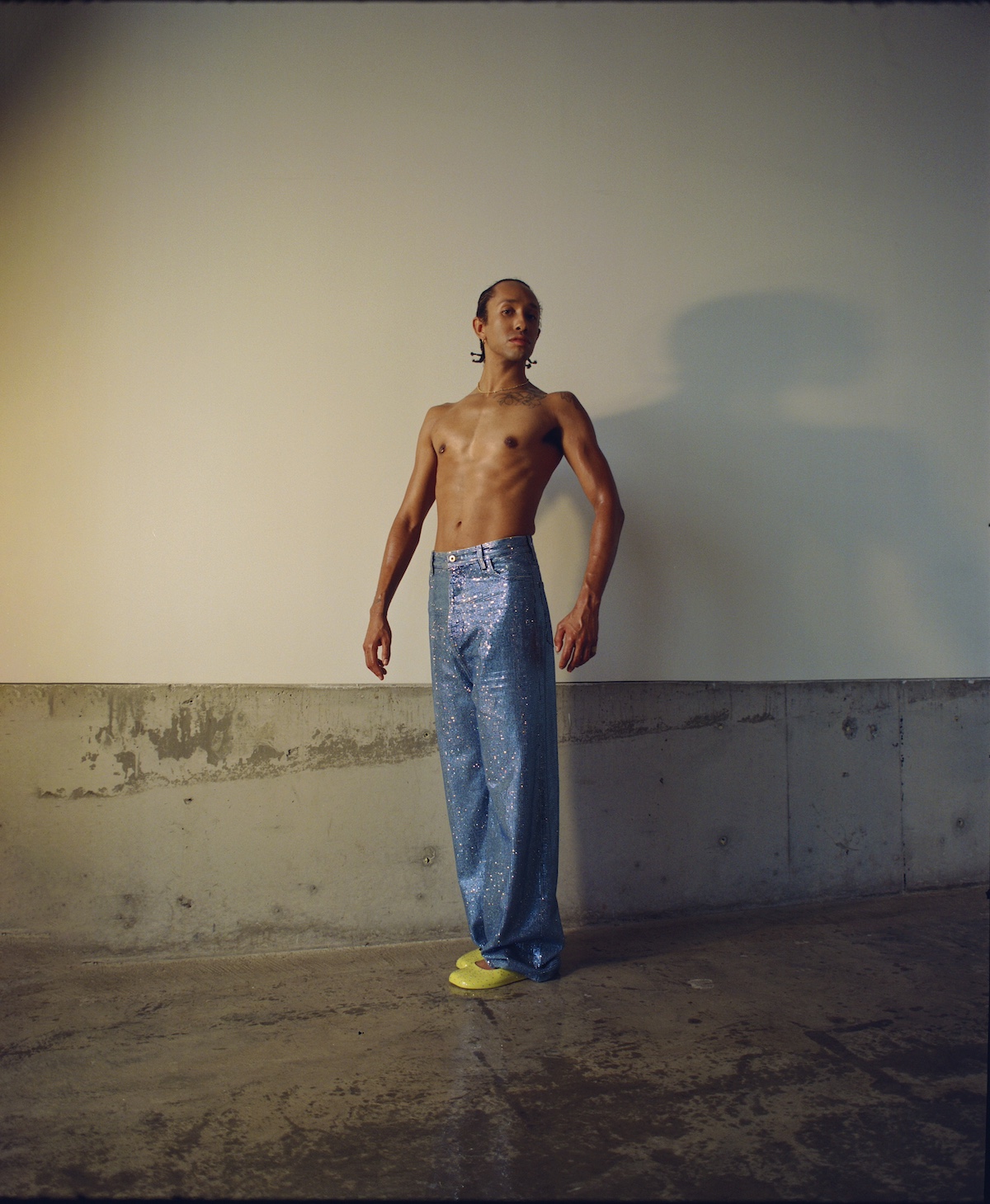

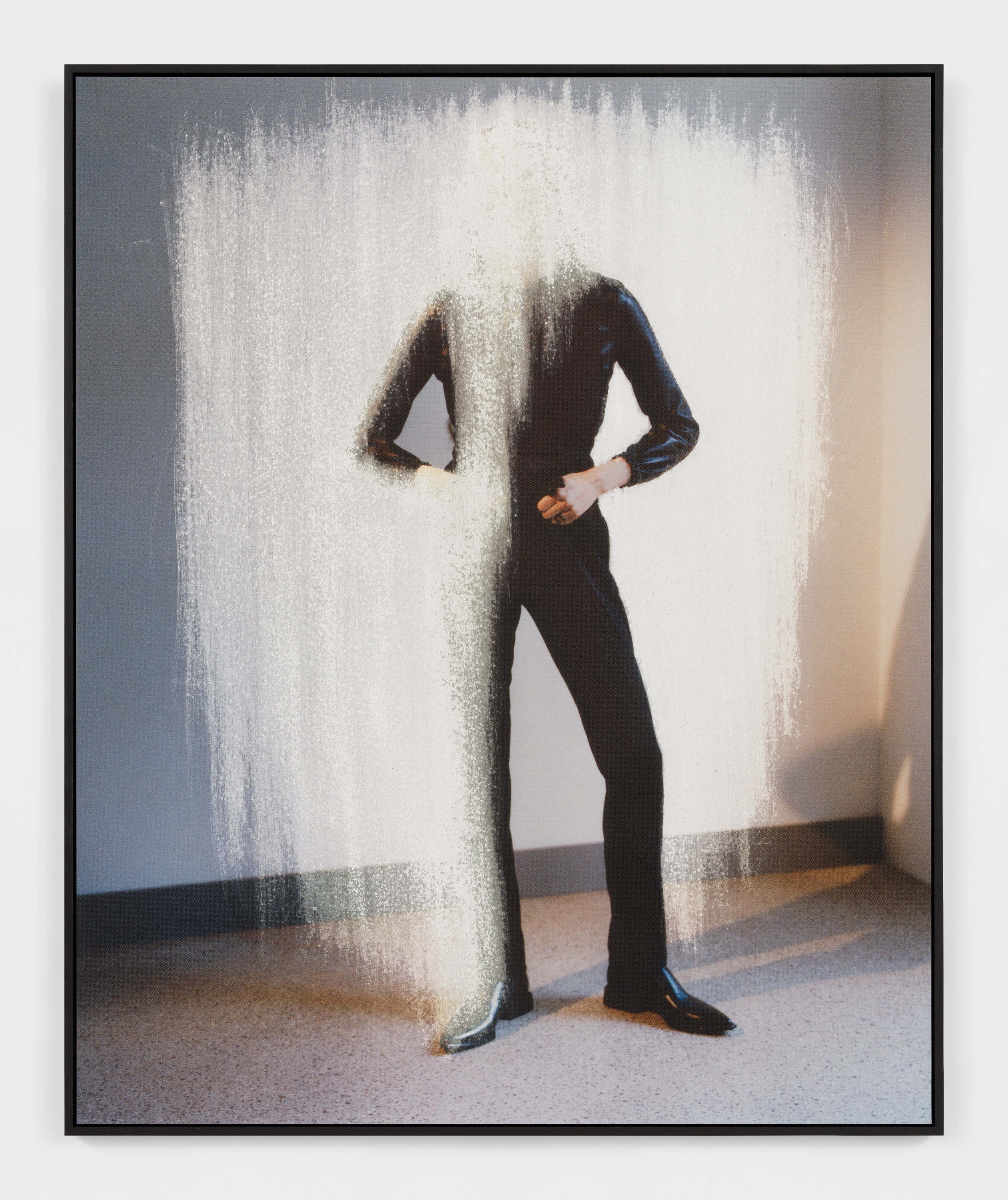

Amie Dicke, Zeitgeist, 2024. Courtesy of Anat Ebgi Gallery.

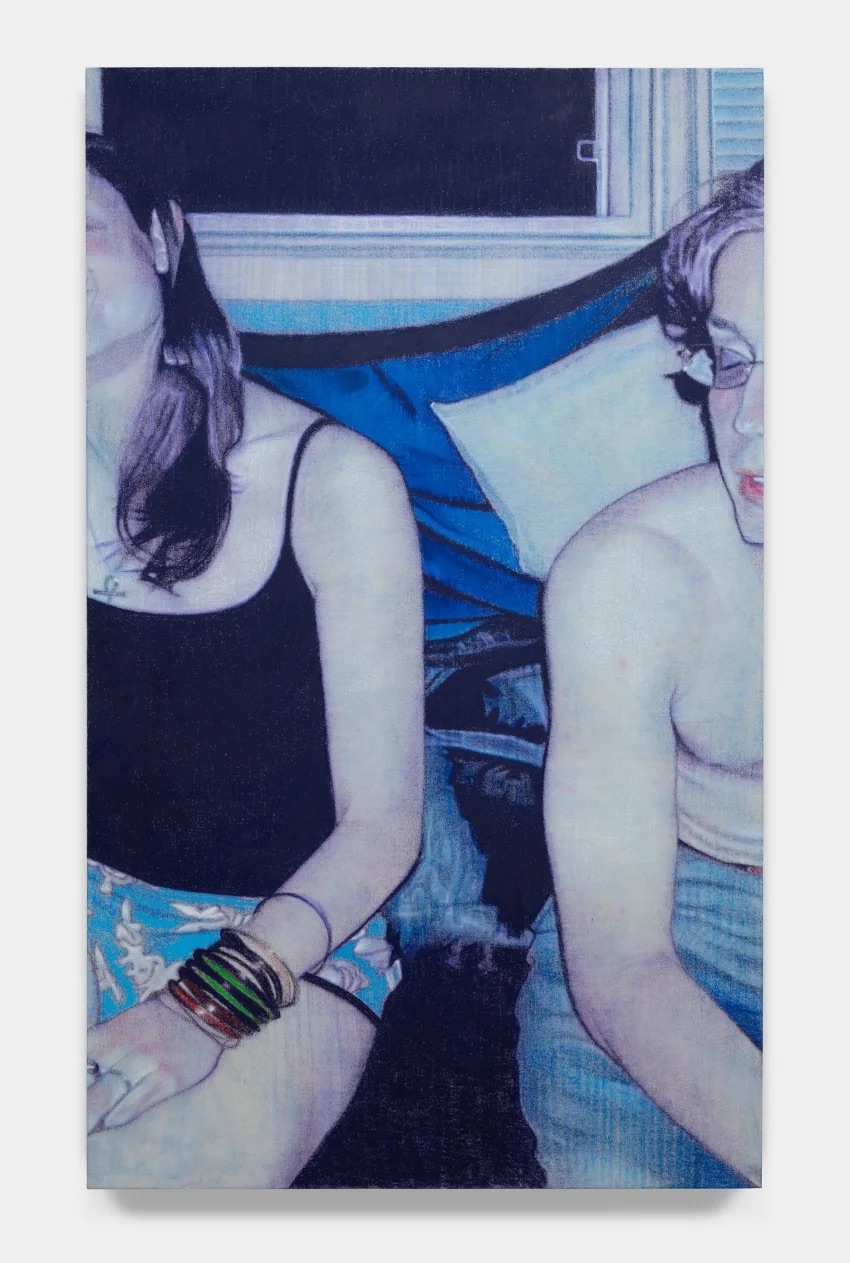

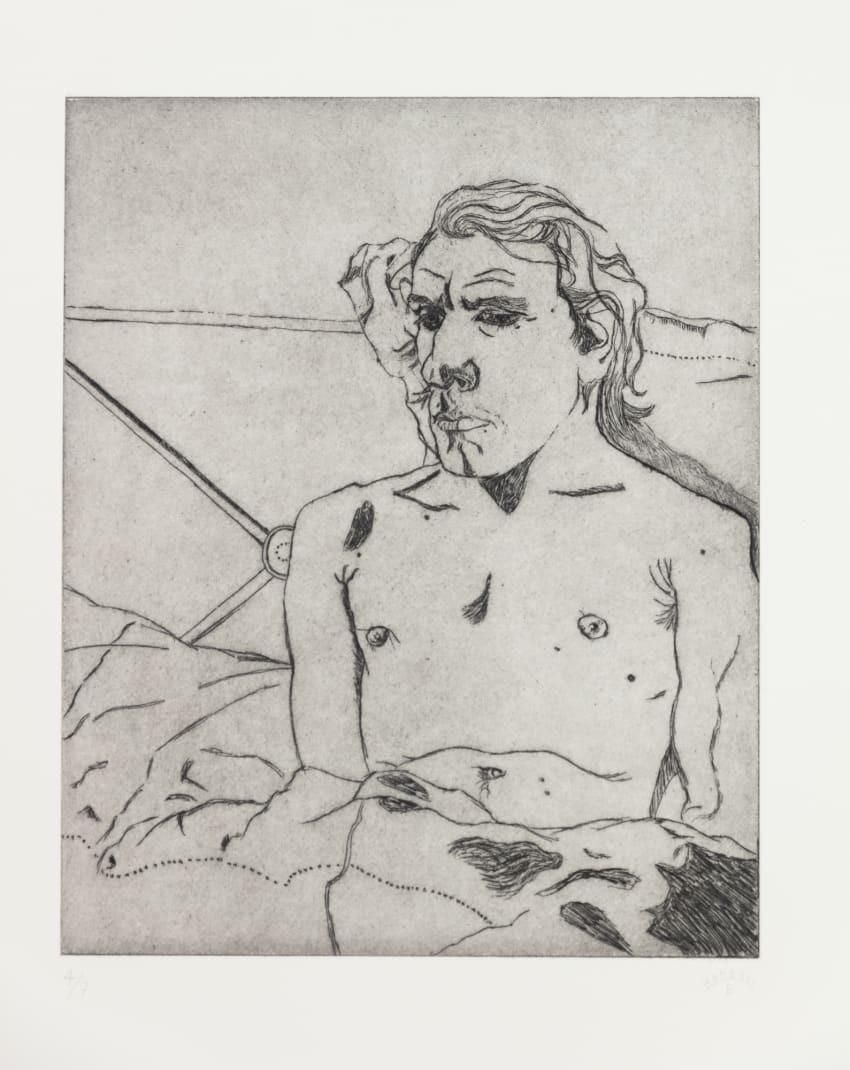

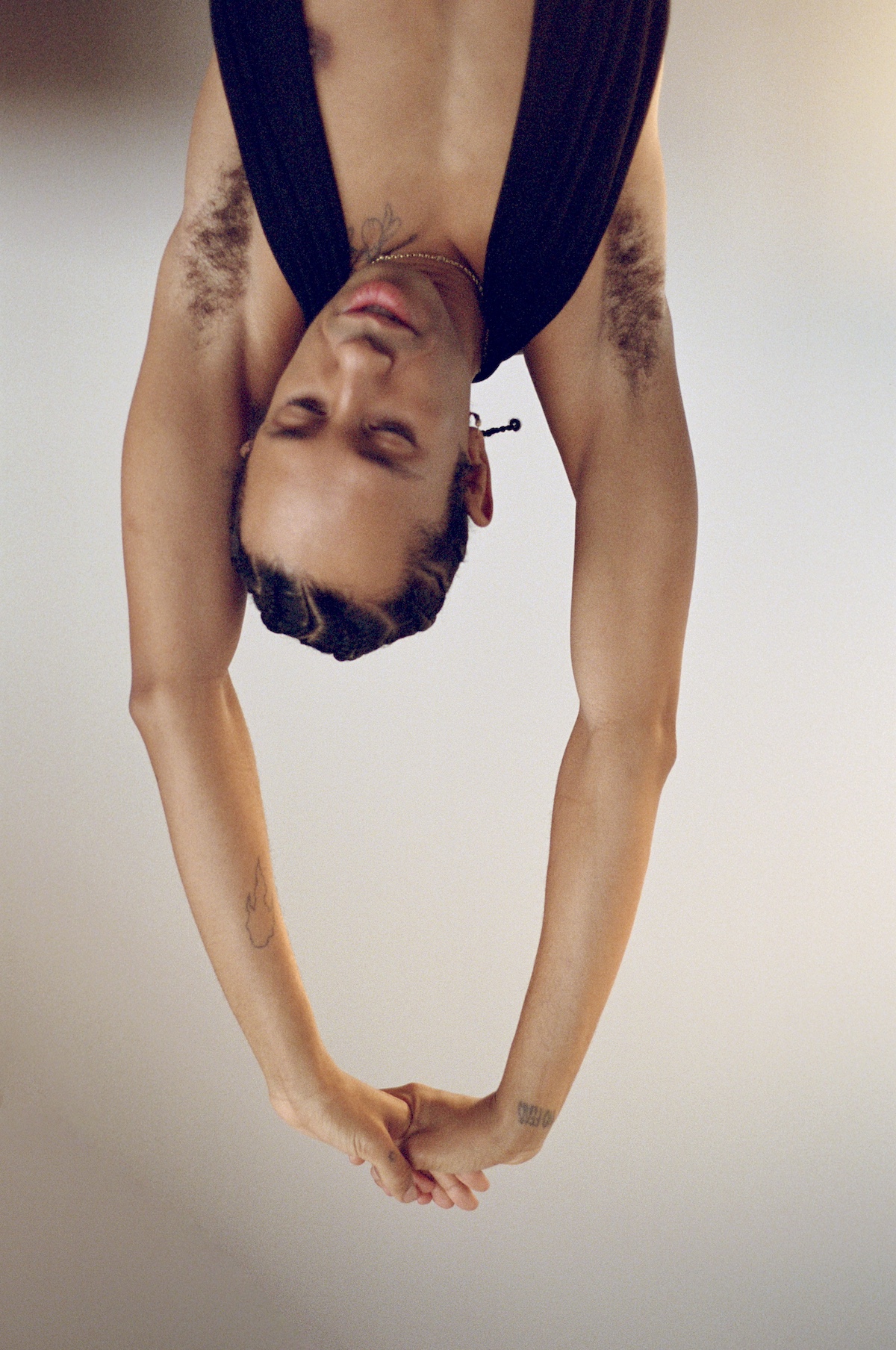

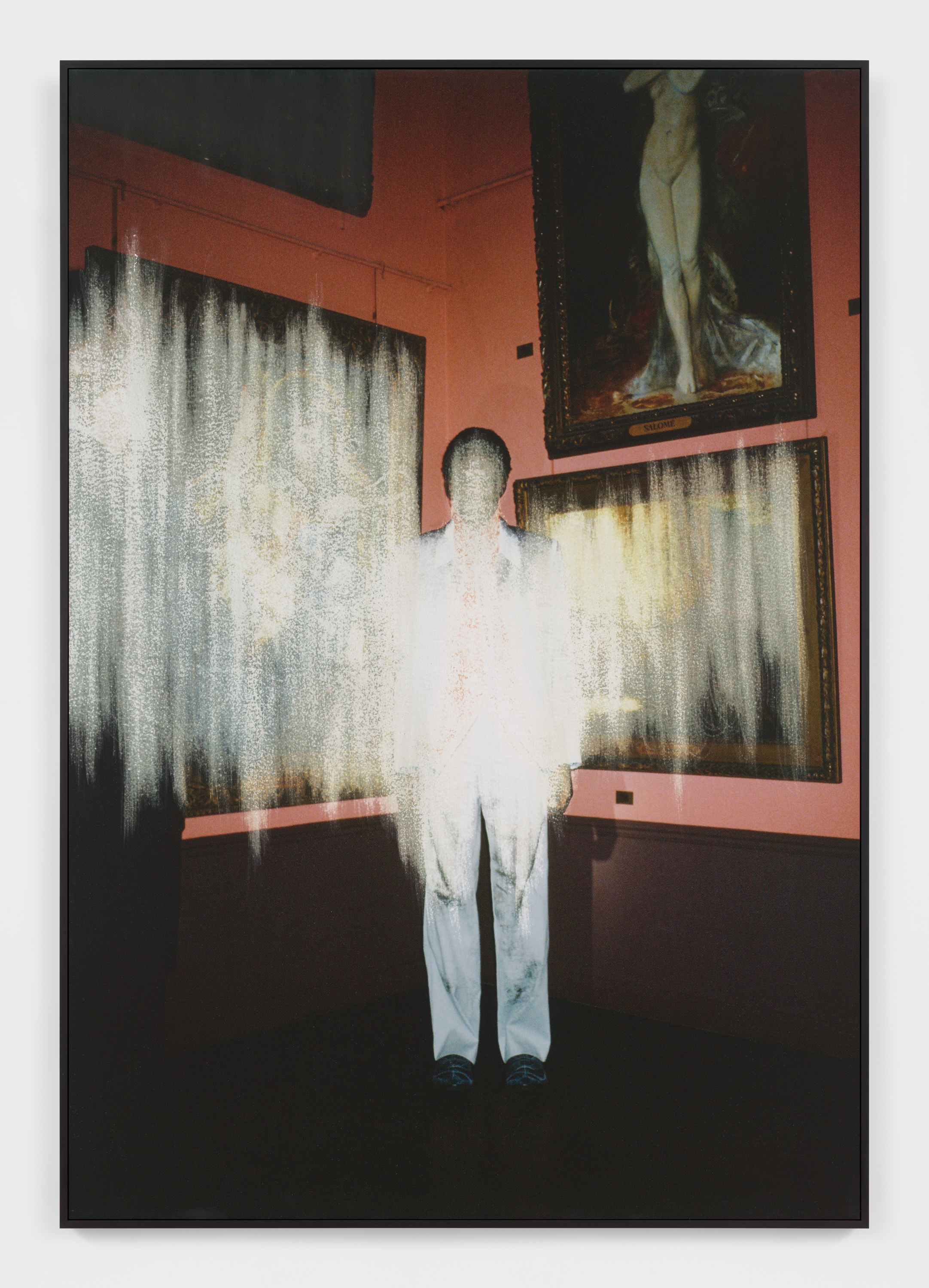

Amie Dicke, Salomé, 2024. Courtesy of Anat Ebgi Gallery.

I also noticed that in this new body of work you have started to work with images of male models. The figures in Zeitgeist (2024) and Salomé (2024) have a more masculine build.

I realized there is something about masculine features, either square face shapes or bigger shoulders, that lend well to my abrasion. The Salomé piece is close to my heart. It was originally a magazine shoot of a male model standing in a museum, with several paintings behind him. I have always been interested in looking at the photographic reproduction of paintings, thinking about how they come to us and what we learn from them. While looking at the image, I saw a nude painting in the top right corner, with her face perfectly cut off from the frame. However, I can still identify her as Salomé by the antique placard placed on the painting’s frame. I was thinking about censoring the title but soon realized how perfect it is in relation to the faceless male model in the front. Salomé famously requested the beheading of John the Baptist.

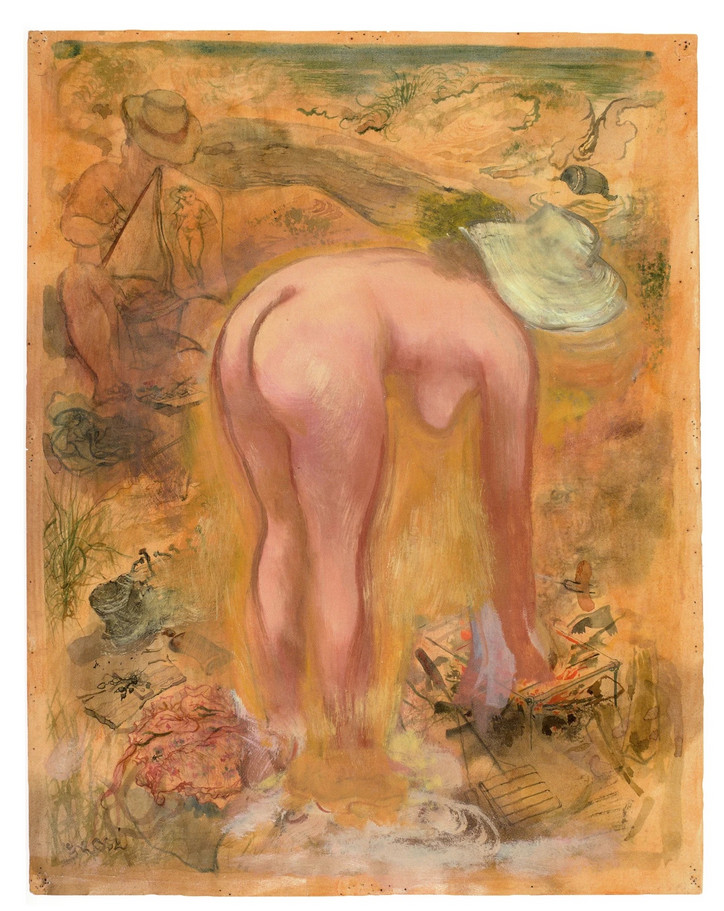

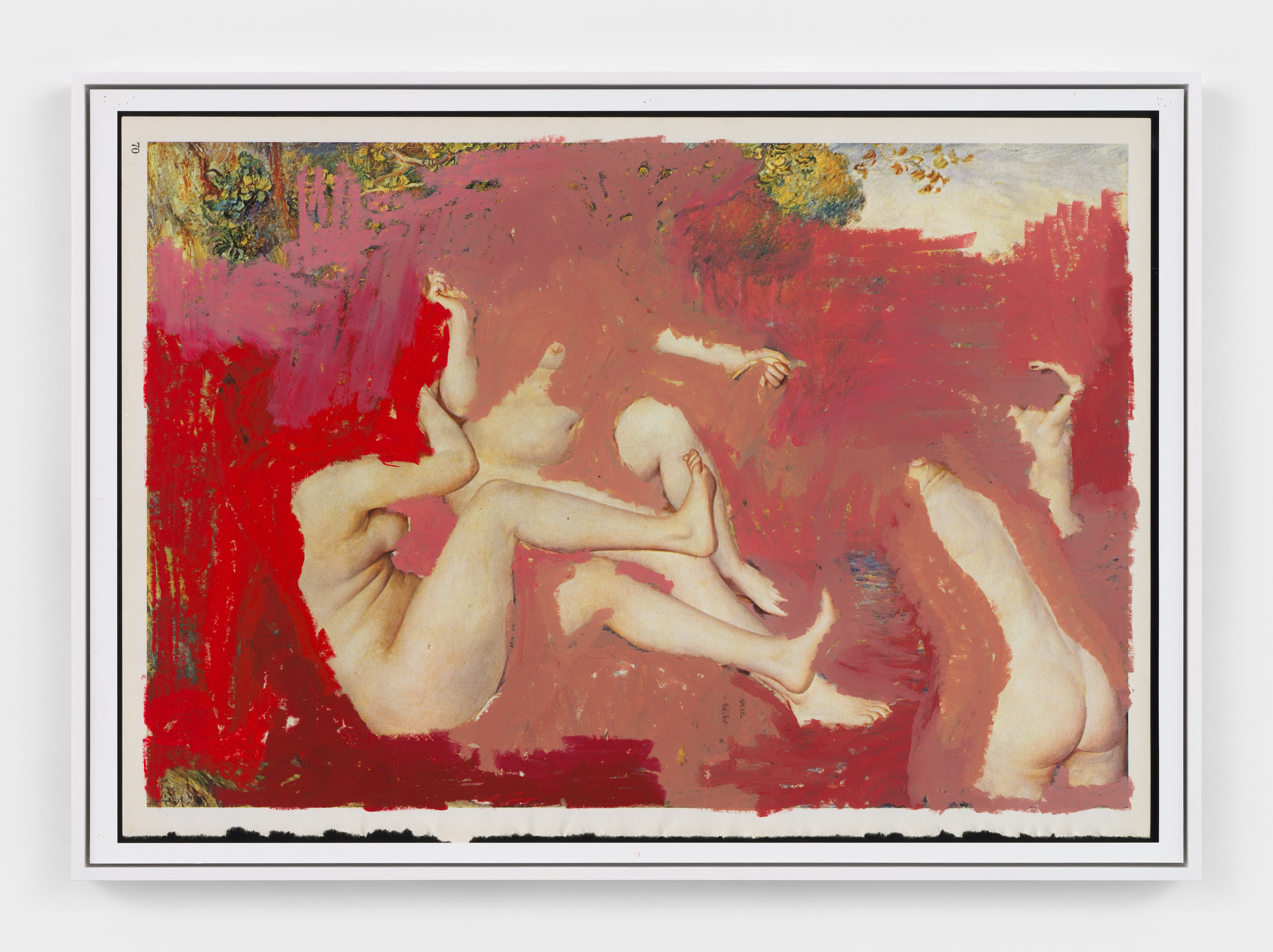

Amie Dicke, The Bathers, 2024. Courtesy of Anat Ebgi Gallery.

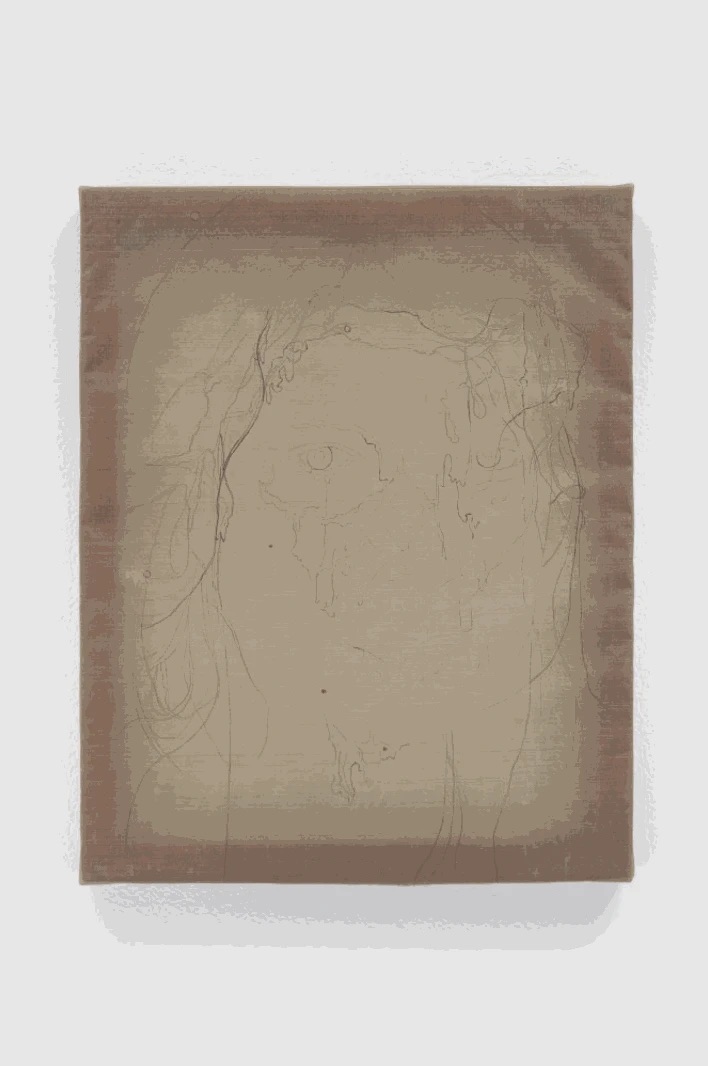

Amie Dicke, Nude, 2024. Courtesy of Anat Ebgi Gallery.

You’ve also started working with the history of Western art itself. The Bathers (2024) and Nude (2024) strike me as full-frontal assaults on their source materials, Renoir’s The Large Bathers (1887) and Manet’s Olympia (1863) respectively. What is your motivation for taking a revisionist approach to these paintings, which are so important to the tradition of European modernism?

I must confess I find it very easy to attack The Large Bathers. I am not really a fan of that painting, and I wanted to question its position within art history. Painting is an act of mythmaking, and I am annoyed at how The Large Bathers reinforces the trope of naked young women being spied on from a distance. I want to see these bathers in a different light so now they are drowning or trying to survive in a sea of lipstick. With Olympia, I am curious about what remains of a reclining classical nude if I take everything away. In the end, Nude takes on a Cubist tradition. Also, you can see a page number on the edges of Nude because I appropriated a reproduction of the original painting from an older magazine. The colors are a bit off, which made my sandpaper intervention more interesting.

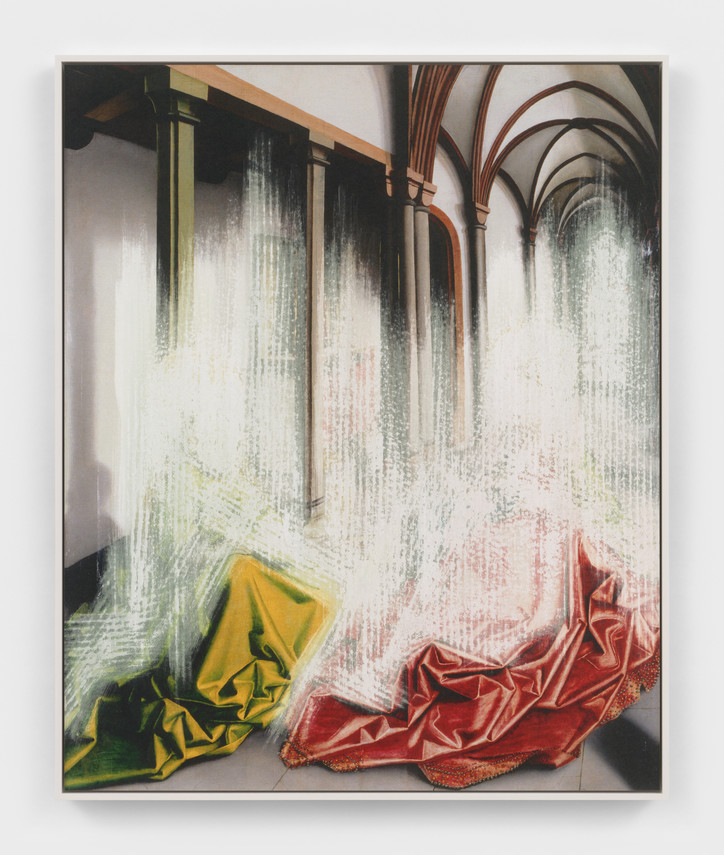

Amie Dicke, Church, 2024. Courtesy of Anat Ebgi Gallery.

Your preoccupation with questions of authenticity and authorship feels most prominent in Church (2024).

Yes, Church is based on the reproduction of a painting I found in a catalog. In the painting, there were two praying figures in a church. I am intrigued by the beautiful, dramatic pleats they are wearing. Once I erase the girls, the pleats take on a very spiritual, almost ghostly quality. In the left corner, you see shadows originally belonging to one of the figures, but now the shadows make the pleats come alive. I was born and raised in a Pentecostal church, so the Holy Spirit is something I am very familiar with.

I read somewhere that your studio is in a church. Is that right?

My studio is in a formerly Catholic church in the center of Amsterdam. I am renting one of the two sacristies next to the altar. The church was secularized but they still have services with another group of Christians on Sunday mornings. Sometimes the church functions as a voting station. Patti Smith performed there too. I sometimes climb onto the altar to find a better Wi-Fi connection. A lot of the days the church is empty, and I am just alone in the building.

Are you still religious?

No, but I still care about the devotional labor in my works. Devotion is very beautiful. I want to be able to train myself to lean into the inner spirits of great literature or painting, and to lean into myself and others. Those emotions and feelings I felt in the Pentecostal church still hold meaning to me. Also, once you have learned how to pray, it stays with you.

I imagine working in a church easily brings out those feelings too.

Yes. Those feelings are everywhere with me. It is more in my heart. Growing up as a young woman in a Pentecostal church and in a very Catholic country, I have always been annoyed by rules and power imbalances within the church. It’s always a man standing there and preaching. Not to mention the Madonna-whore complex. In the Bible, a lot of the female characters are usually sidelined or just presented as a temptress. I want to represent them differently.

Are you then freeing women from the confines of great books and modernism?

I’m not sure if I am freeing them, but I am freeing myself. Maybe at a certain point I will be really free, then I am curious what I am going to make. Too much freedom is panic, right?