The Artist and the Cigar Box: Civil Pleasures

Check out photos from the opening night below and put your bids in here. The Artist and the Cigar Box online auction.

The Artist and the Cigar Box is on view online through June 30th.

Stay informed on our latest news!

Check out photos from the opening night below and put your bids in here. The Artist and the Cigar Box online auction.

The Artist and the Cigar Box is on view online through June 30th.

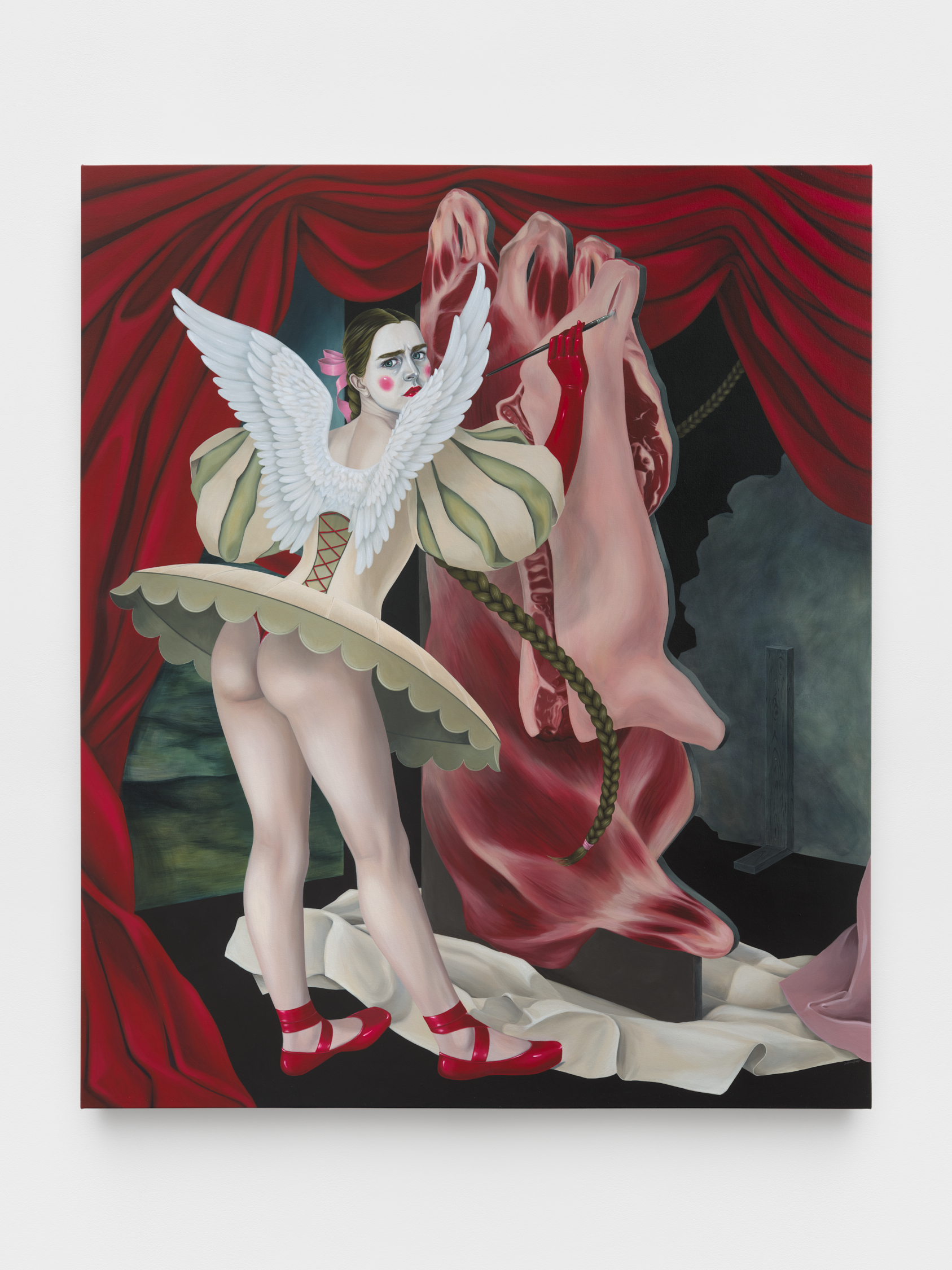

How is The Grumpy Girls a departure from your previous shows?

My last show was really a linear narrative and The Grumpy Girls is a bit more of an abstract narration. There’s not a clear beginning or a conclusion to the story. It’s giving you the different pieces and you can arrange it in whatever way speaks to you.

It’s a bit of a technical challenge for me. I had never worked with multiple figures this way before, especially in the large works. I would say it’s an evolution [of my previous shows] I’ve been working conceptually with the same ideas… motherhood, sacrifice; this before and after of motherhood.

It seemed very crucial for the girls to be grumpy. Why is it important for the grumpiness?

It takes this very serious idea and winks at you a little bit. I like this idea that they’re doing this labor, they’re braiding this hair or preparing the scenes, but they’re not thrilled about it. There’s reticence, they’re begrudgingly doing this work in service of the play, the film, however you see it.

Having them openly frowning is important for that to convey their unwilling participation. And also frowns are very fun to paint. It’s fun to paint these frown lines. More traditionally in representation of women in painting, we don’t really see a lot of anguished, frowning faces — that’s more rare.

What was the creative process?

It started with a sketch that I made in the summer. The sketch became the artist, the winged figure and she was initially facing the viewer and looking very stern, very grumpy. And I like this defiant gaze. I kept developing that sketch and started building out these other iterations of that character, so the girl and the mother. And at some point, I realized they all had to come together. That’s when this fourth figure emerged, this nude self that they’re all sort of working in service of and the rest of the show was about paintings that would support the storytelling of these four works.

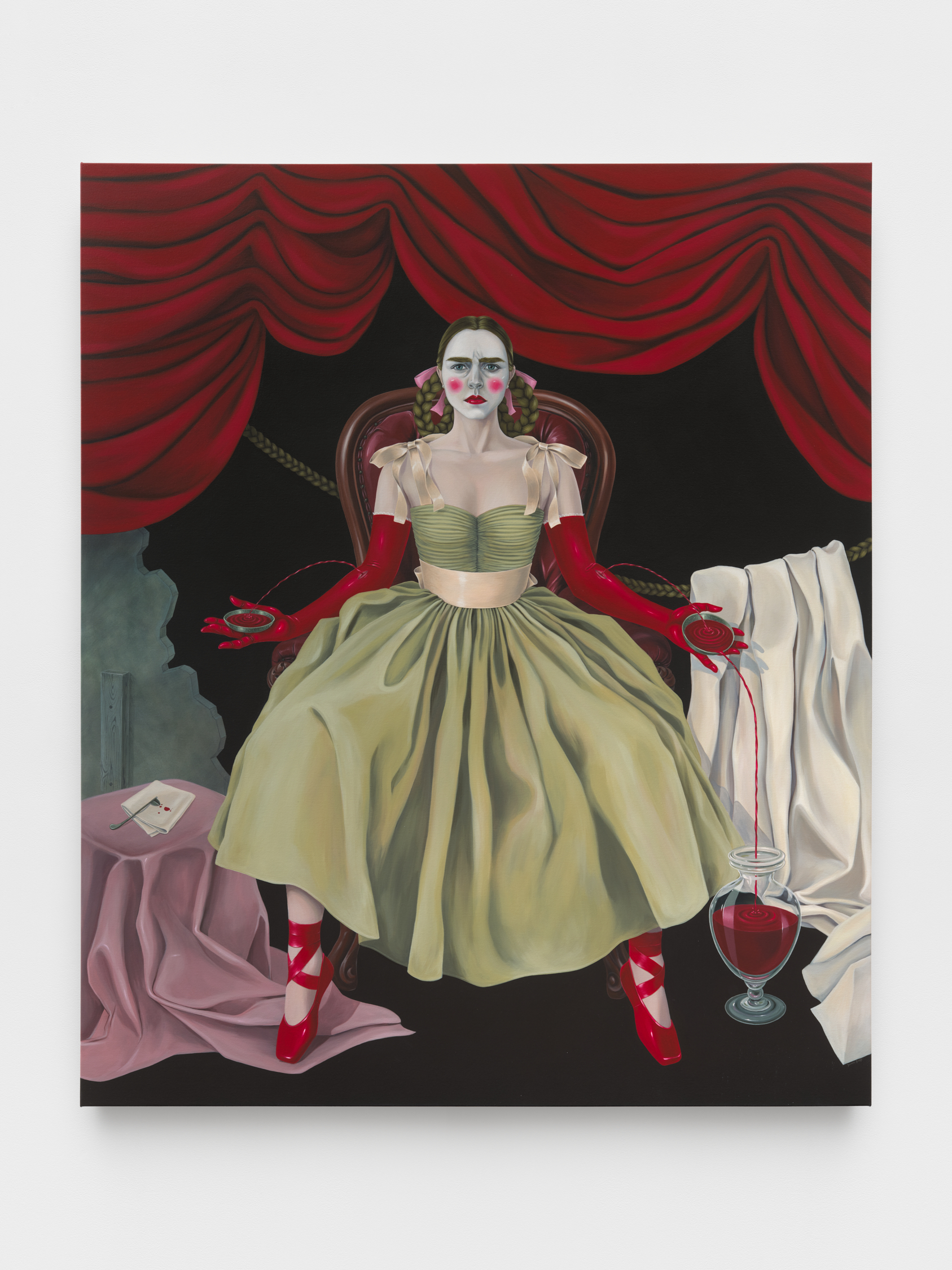

There’s a lot of technicolor theater and costuming references. How did you choose those cross-references to come across in your work?

I really like that era of cinema. The Red Shoes is something I referenced in my last show as well and I continue to go back to. It’s such an interesting story and thematically it really aligns with this show in that it’s really about whether art making and a full life can be compatible, which is the question that I’m asking with this mother figure who's disrupting the braiding scene with the scissors. What are the elements I need to let go of to make space for this new identity? What things need to be sacrificed to be a mother? And what of those things need to be sacrificed to be an artist?

What conversation are you having with yourself through the paintings? Like presenting yourself as a visual artist and pulling back the curtain… what’s going on internally with that?

There’s a degree of vulnerability. But there’s still the veneer of guarding myself, I suppose. The nude figure is most representative of that — laying there like a beach siren nude, but she still has the [opera] gloves and is still wearing the makeup. It’s sort of me saying I allow myself to be vulnerable to a point in my work. And I think that’s where the camp, winking, tongue and cheek element plays in too, because I’m taking these very serious, heavy ideas — it’s adding something acidic to something very fatty.

Especially with these three archetypes, trying to interrogate different aspects of myself. The blood letting one especially is me unpacking my vanity and my relationship to beauty culture and beauty rituals. I’ve seen so many videos lately about simplifying your skincare routine and I used to be a 12-step [skincare] girlie and I honestly don’t know if it was helping. Historically, when you look at these really dangerous beauty practices like lead face paint, those women never knew they were hurting themselves at the time. While the other archetypes are a bit more reflective, the mother is hypothetical — I’m imagining a future version of myself.

It’s definitely portrayed that there’s this cost to girlhood or womanhood. What was it like to portray that cost?

That’s a perpetual tension in my work. The desire to paint a beautiful figure, but to also represent myself in a way that feels honest to me and navigating beauty ideals in painting and media more broadly. Having pubic hair in a painting, I heard from other artists that they were discouraged to have women’s body hair in paintings and then at the same time, my figures don’t have armpit hair or leg hair. I’m battling my own internalized ideas about beauty standards. As I make more work where I push myself to resist [beauty] ideals more, I notice I become more comfortable in my own body in my real life.

How has your previous experience in fashion contributed? I noticed the opera gloves in the pieces…

Costuming is very important to me. It’s very fun to paint dramatic folds and poofy skirts. The costuming can tell so much of the story for you too. The artist is the most free version of myself so she has these wings and this tiny little tutu that’s a contemporary version of a tutu and it shows her legs and her butt.

The gloves have been a barrier layer, there’s sensuality to the [opera] gloves, but actually whatever is being touched by the hand in the glove is not being touched by the hand itself. I like the sensuality of that restriction. I like to have these feminine elements in contrast to blood and meat, these more grotesque images.

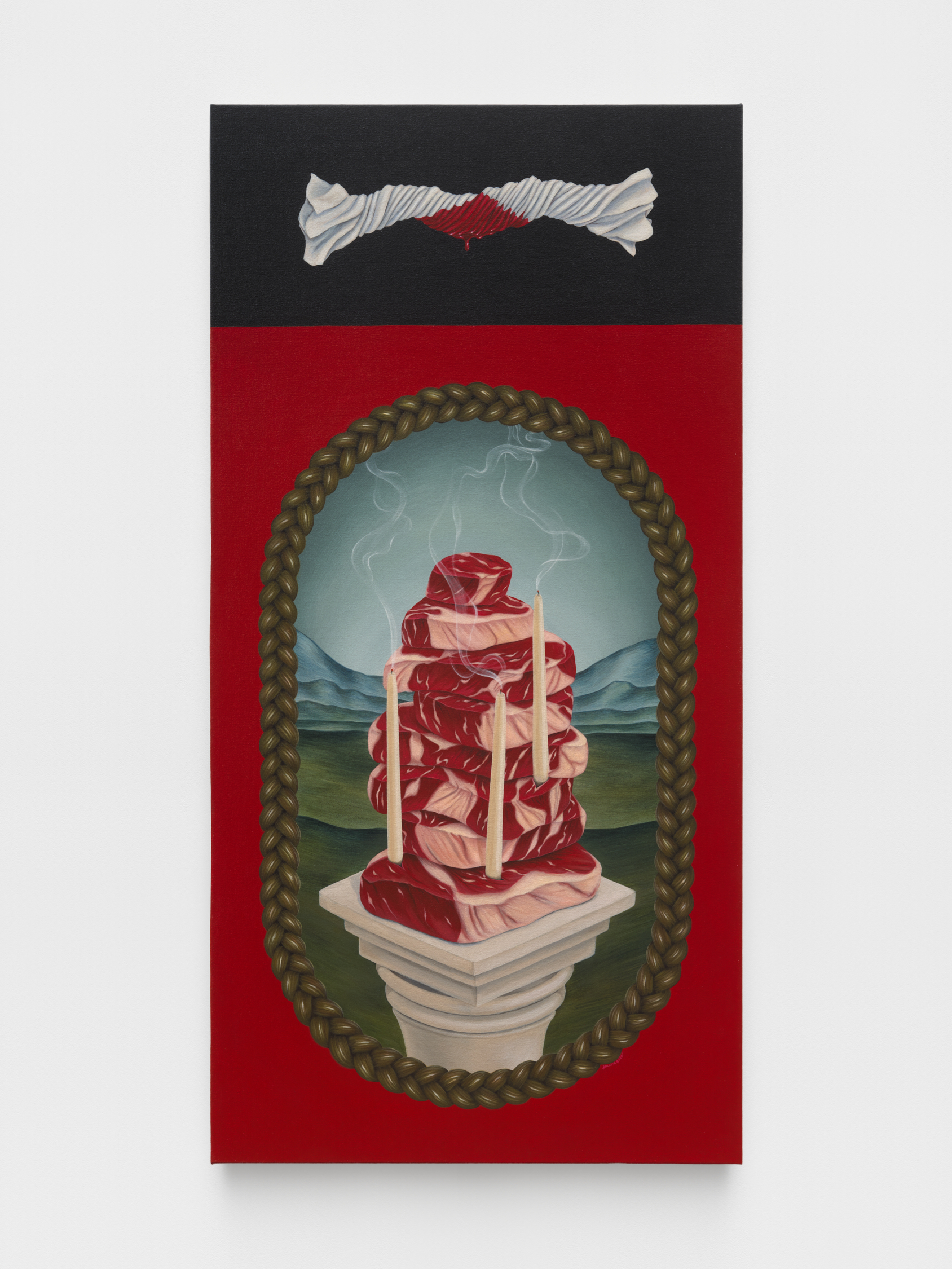

What made you think Oh, I’m going to have this ballerina paint this meat carcass? What was the symbolism behind the carcass? Is it a meditation on femininity?

She’s painting a set piece. So the idea is maybe there’s a slaughterhouse scene that we’re not seeing. But also it’s a nod to my previous work where I’ve painted a lot of meat. She is the archetype that I identify with most at this moment. I like having her in this meta… her painting meat while I’m currently painting [her]. Meat in my work is a symbol for the body. Meat being decontextualized from a consumption context makes it feel a lot more fleshy. This metaphor of earthly flesh, decay, there’s an ephemerality to it — it’s fresh right now [the meat] but it won’t always be.

It’s pulling back the curtain while also showing the stage. How did you manage to capture both?

That’s the duality of these feminine touches and having them directly alongside bodily horror imagery. That it’s staged suggests there’s an artifice here. The surfaces are really smooth and they’re varnished with this fat and finish that gives them this weird quality that’s almost like you’re seeing it through a screen or a piece of glass. It’s a performance — an image that’s not totally solidified. There’s a degree of removal.

Out of all the things you could paint… what’s so interesting about self-portraiture to you?

During Covid, I was stuck at home and this is what I had to work with. It was also a way to project myself into fantasy settings and scenarios that weren’t accessible to me at the time because we were locked down. That’s the origin and now it’s really about trying to know myself, to be corny. I discovered so much about my wants and desires in making these paintings. The things that I’m unpacking or saying at the outset of a body of work develop and surprise me by the time I finish it.

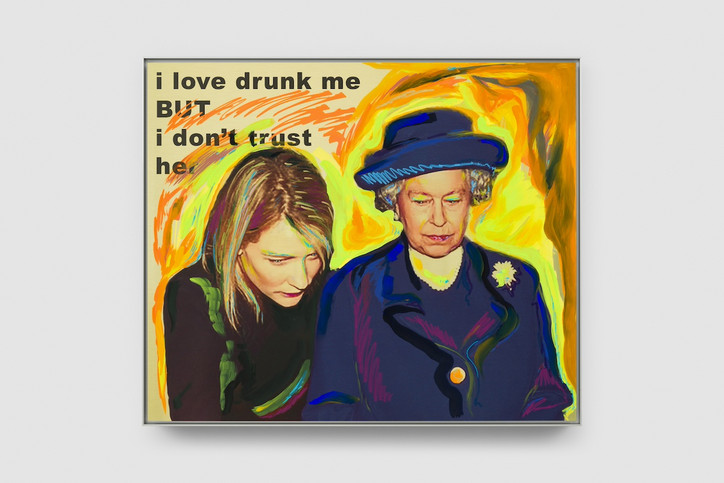

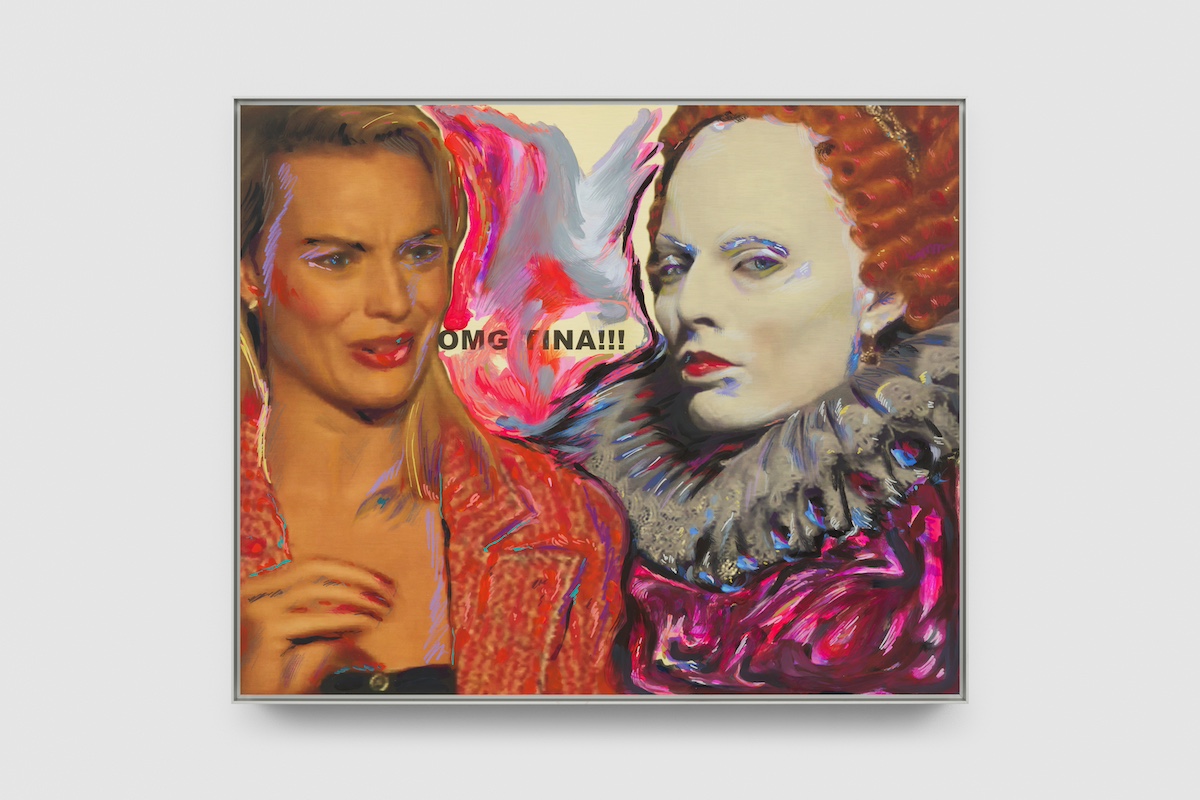

Urban Dictionary defines “White Girl Wasted” as “the phenomenon which occurs when a person consumes too much alcohol and proceeds to embarrass themselves and their friends for however long they remain conscious.” You know it when you see it: the dancing, yelling, singing, fighting, crying. It’s a tale as old as time — or at least as old as tabloids and celebrity gossip blogs. Celebrity scandals are cash cows for mainstream media outlets, capitalizing off the ugliest moments in an otherwise carefully architected Hollywood landscape. Ultimately, the media needs young starlets committing acts of self-destruction for their own publicity and revenue. Simultaneously, the star benefits from the attention too.

In Cara Benedetto’s solo exhibition WGW at Rose Easton Gallery in London, she explores the construction of white femininity and victimhood, critiquing what society thinks women in power should look like. Instead of portraying Elizabeth I herself, Benedetto depicts a polished Margot Robbie side by side with herself as the character, with the caption “OMG TINA!!!” Similarly displayed is Kristen Stewart, doubled as the late Princess Diana with her signature closed mouth smile and baby doe eyes. The facial features of Stewart reveals a yearning, one that mirrored Diana’s throughout her time as the Princess of Wales, signaling someone to save her from the circumstances and her own personal self-inflicted hell. Through her depiction of chastised historical figures and the celebrity actresses that portrayed them, Benedetto illustrates even the most privileged woman can’t help but self-destruct — but when they do, their appearances afford them a level of grace denied to most. They are vindicated by the spectacle of their spiral, because we choose to be front row viewers of the trainwrecks we can’t look away from.

In a PowerPoint video titled Hill and Lizzy @ Kegger, Hillary Clinton asks Queen Elizabeth if ‘she’s seen her bong?’ Benedetto at first, seems to be making a more tongue-in-cheek pass at the two. She subtly critiques the brashness of the subjects, yet treads towards a more nonchalant response satirizing a neo-feminist or “girl boss” take. Perhaps in 2016, at the peak of Women’s Marches and Trump protests, Benedetto would have had an explicitly critical response to these women in power through a more preachy form of captioning and symbolism. However, the paintings are indicative of changing socio-political stances and a feminist rejection of a monotonous political climate.

Benedetto neatly intertwines both an unattached and critical worldview within her work, presenting these truths for what they really are without feeling moralizing or singling out viewers. Instead she displays the indexicality of the current time period through witty details and symptoms of a generation coping with perpetual and deliberate melancholy. Labeled the Fleabag Effect, the last decade has seen a gradual shift among millennials and Gen z adopting a more dissociative attitude towards their own suffering and romanticizing self destruction as a form of coping with both external and internal triggers. It’s no coincidence that books such as Otessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation and Didion’s Play it as it Lays have dominated the literary spotlight amongst Gen Z readers. Both characters choose to self-sabotage within the enclave of comfort, monetary stability, and whiteness, despite having the resources to thrive. At times it feels illogical that we keep reading these stories and spotlighting these women, even as more dire global issues continue to compete for media attention.

In the simplest justification, and in true Fleabag fashion, it’s fun to check out from the pressures of the world, especially if you inherently hold the privilege to do so. People love these stories about this type of woman as a way to live vicariously through someone whose conventional beauty and status allows them to suffer virtually no consequences. They will continue to live a life of relative ease as long as the mess they create while doing it toes certain social and legal lines. People will choose to read about a girl walking around New York in Prada ballet flats, defecating in the foyer of an art gallery she used to work at because she got fired. This doesn’t mean she should be used as the beacon of morality and fairness, but who doesn’t enjoy imagining a life spent following all of one’s worst impulses?

WGW is on view at Rose Easton Gallery until June 15, 2024.

Robert Greene, the author of The 48 Laws of Power once said that power is an invisible realm that envelopes society, where people continually battle each other though no one is trained to talk about it. Only when you make mistakes do you realize how political people are.

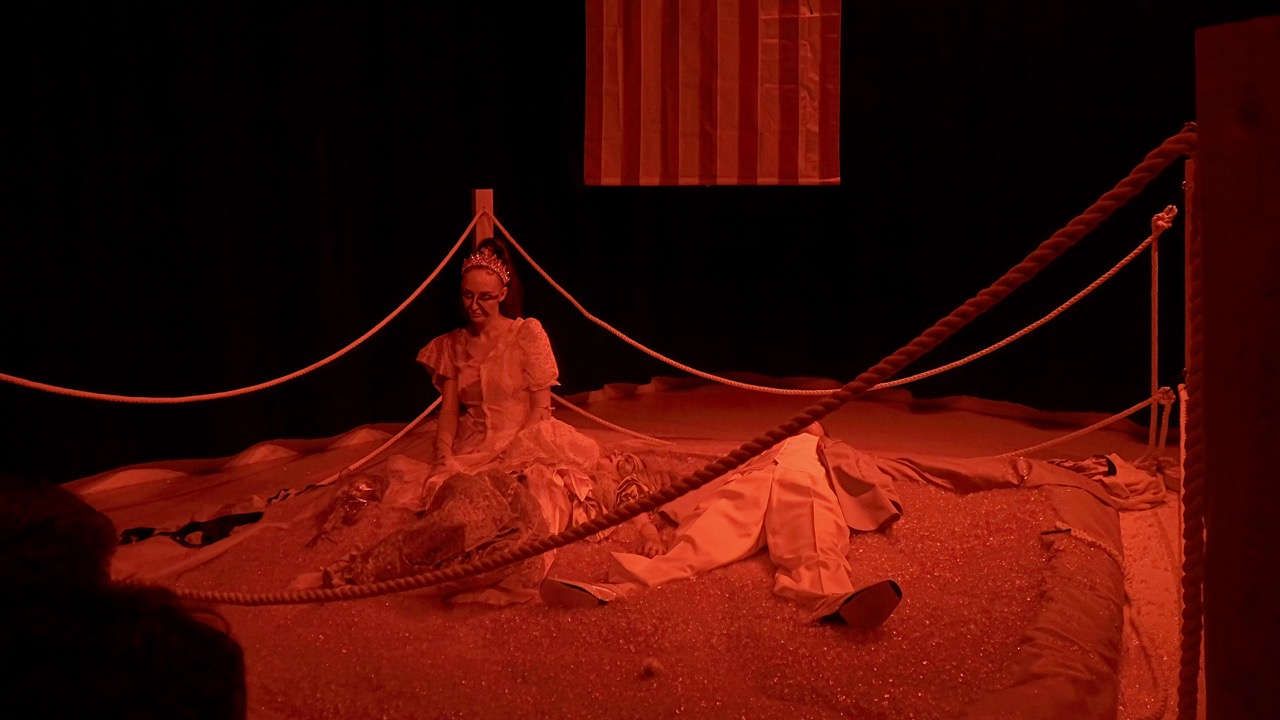

The rules of the game are simple, a referee in a fetish mask (Joshua Weidenmiller) exclaims to the crowd. Please. Don’t. Hurt. Me. Borrowing lines from Brache’s poems, the actors’ fragmented dialogues are a jarring display of cognitive dissonance in a three tableau narrative involving sports, the psyche, and polite society. The opponents, named Nothing Girl and Mary Magdalene, face each other in front of the nation’s flag, topping each other from the bottom, moving in-sync, writhing in a pool of red gelatin. The audience laughs, not knowing what to expect next. In the second scene, Josh plays an analyst examining Betsey in a lounge chair, an element of Jungian and Freudian influence on the night’s inquiries. Among those inquiries, the show’s co-directors probe into America’s obsession with the masking of oneself in order to survive and exist in reality; the juxtaposition of constraint and consequence deeply embedded in our daily roles.

“Sports mirror the facade of contemporary life,” Sigrid describes her and Brache’s vision for the evening, or poetry in motion, as she calls it. “We’re expected to perform, constantly pitted against one another within the capitalist machine under the scrutiny of a faceless judge.” One summary of the show could be more or less a marriage of central ideas revolving around interdependence, the unconscious, and PsychologyToday.com.

The third act ends with a play off of a prom scene, a celebratory tradition rooted in gendered competition and peer judgments. It would make sense that the use of Jell-O also holds origins as a 20th century symbol of another American invention—specifically aspic, molded vessels that once encapsulated long hours of domestic female labor as privileged entertainment. Inspired by the fetish magazine Blushes, Brache’s book cover depicts an AI-generated image of a mannequin-like woman with a man pouring water over her legs, imbued with an idyllic quality aesthetically referencing JCPenney catalogs from the ‘80s and conventional (or otherwise sanitized) notions of beauty.

Victorian era music plays in the background. Nothing Girl pushes Mary forward, who prays on her backside. Why does being sick last so long? She screams. “She’s sick because she’s staring at her reflection,” explains Sigrid. “She’s sick because she is using others, because she has to work too much, or maybe, because the machine is sick."