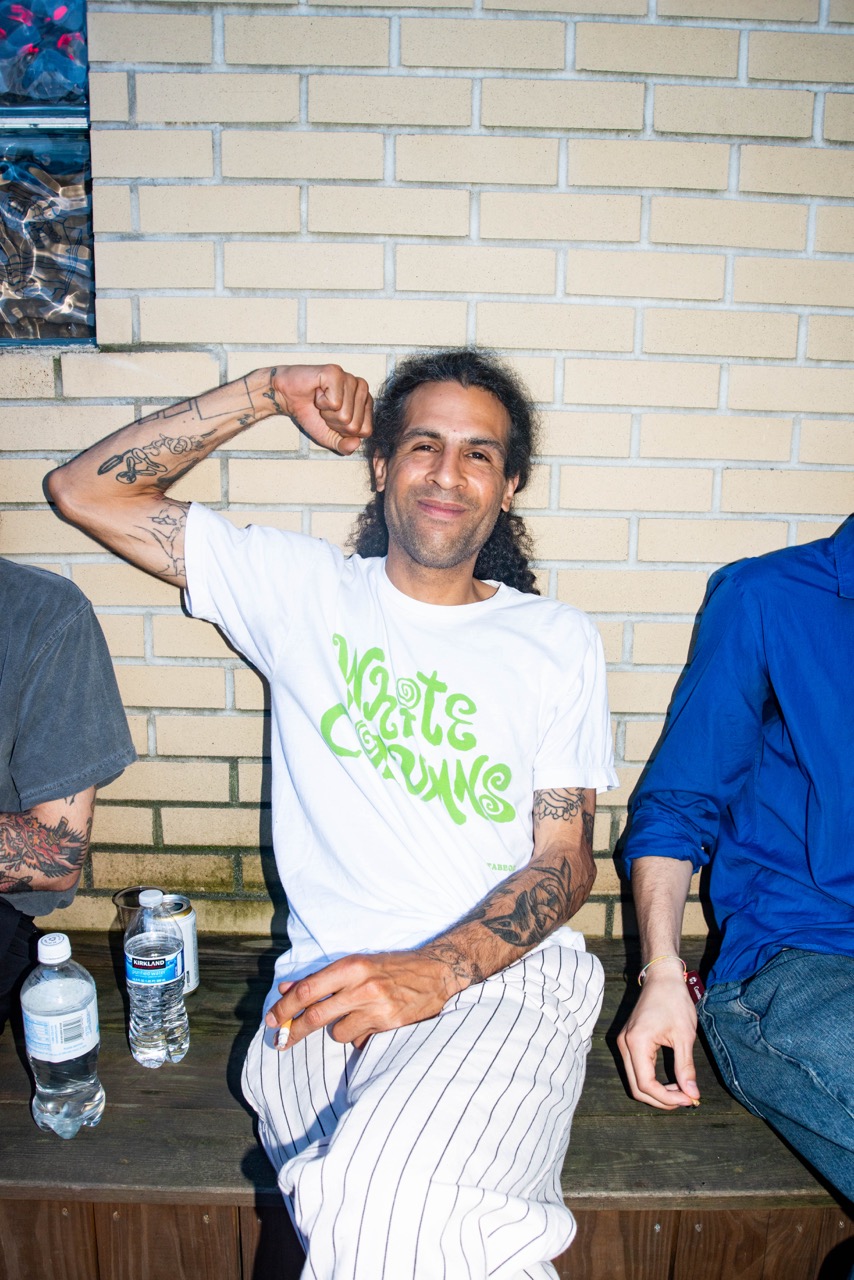

The Artist and the Cigar Box: Civil Pleasures

Check out photos from the opening night below and put your bids in here. The Artist and the Cigar Box online auction.

The Artist and the Cigar Box is on view online through June 30th.

Stay informed on our latest news!

Check out photos from the opening night below and put your bids in here. The Artist and the Cigar Box online auction.

The Artist and the Cigar Box is on view online through June 30th.

I had the opportunity to interview Nishimura during her visit to New York. As we strolled through Fort Greene Park in Brooklyn, hearing about her journey leading up to her debut solo exhibition in New York, I couldn't help but think of the words of minimalist artist Carmen Herrera, who broke through at the age of 89, and Swedish artist Hilma af Klint, who refrained from exhibiting her work for 20 years after her death.

Yes, in their worlds, delays occur and time often lags.

"There is a saying, 'If you wait for the bus, the bus will come.', I say yes, I waited almost a century for the bus to come, and it came." — Carmen Herrera

Such delays were of no consequence. They each continued to pursue their paths in their own way.

And so Carmen Herrera waited for the bus, Hilma af Klint calculated the time difference, and Tamiko Nishimura kept on her journey.

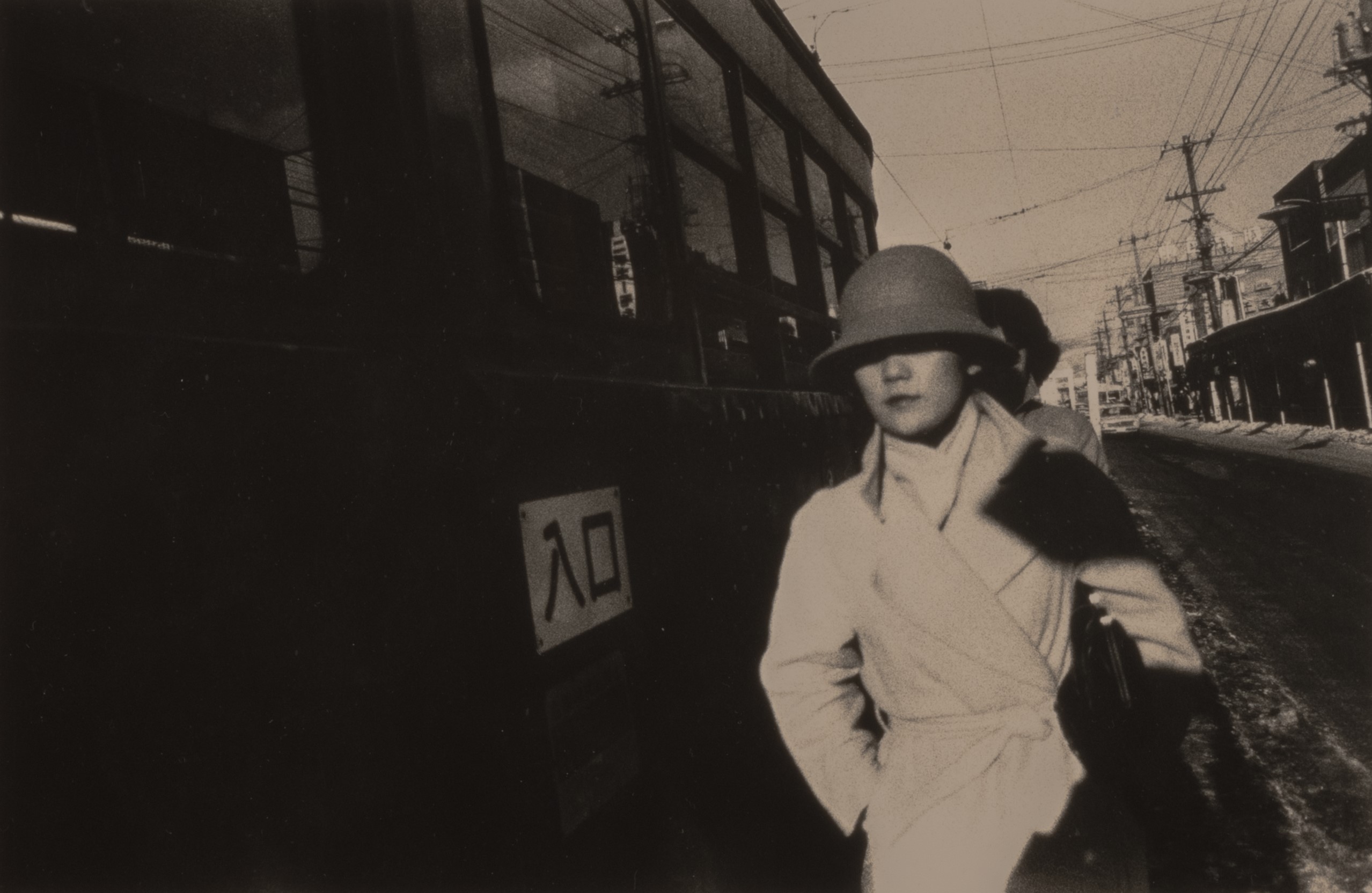

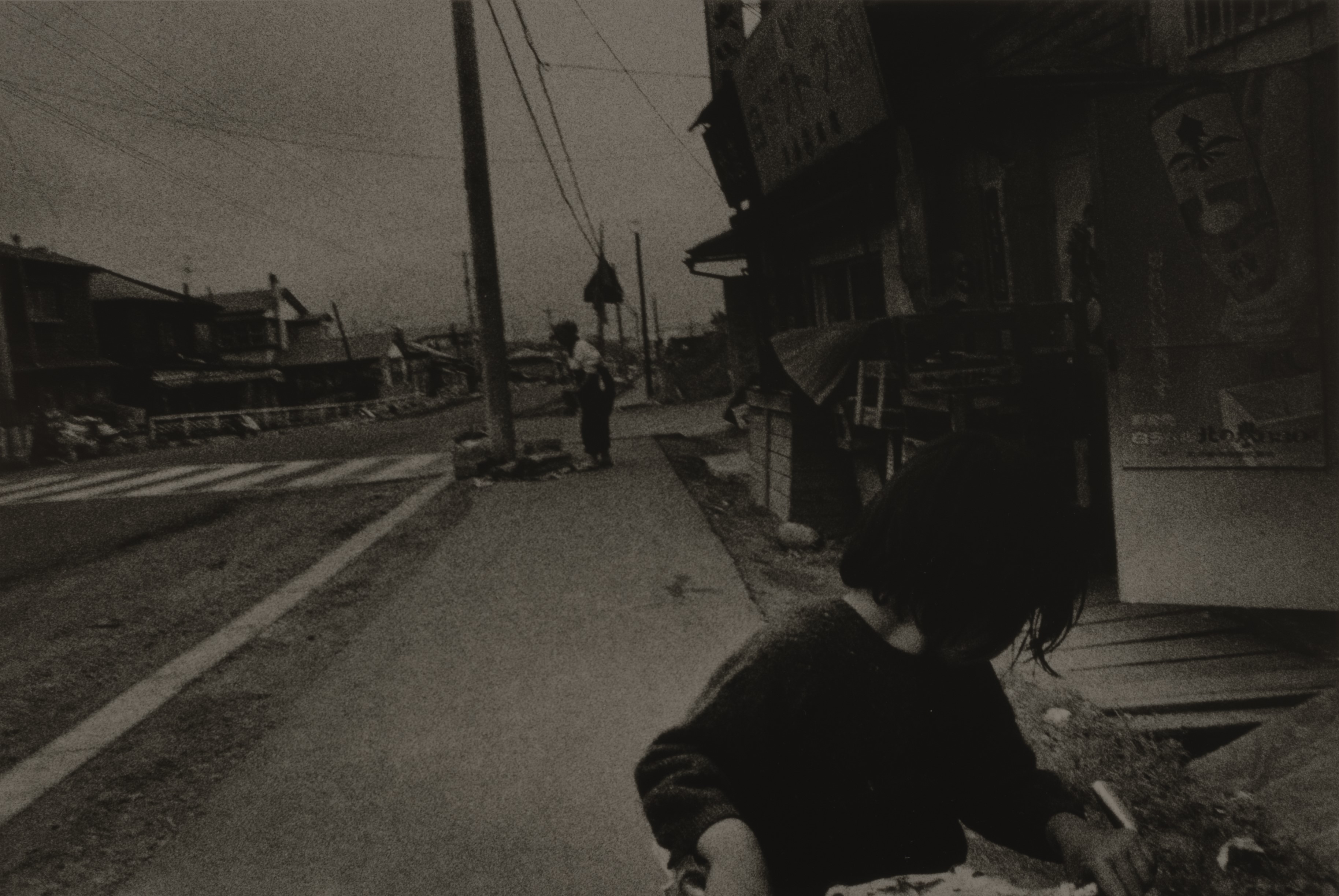

Eternal Chase (2012)

Tamiko Nishimura — I wonder if younger generations are interested in this type of photography.

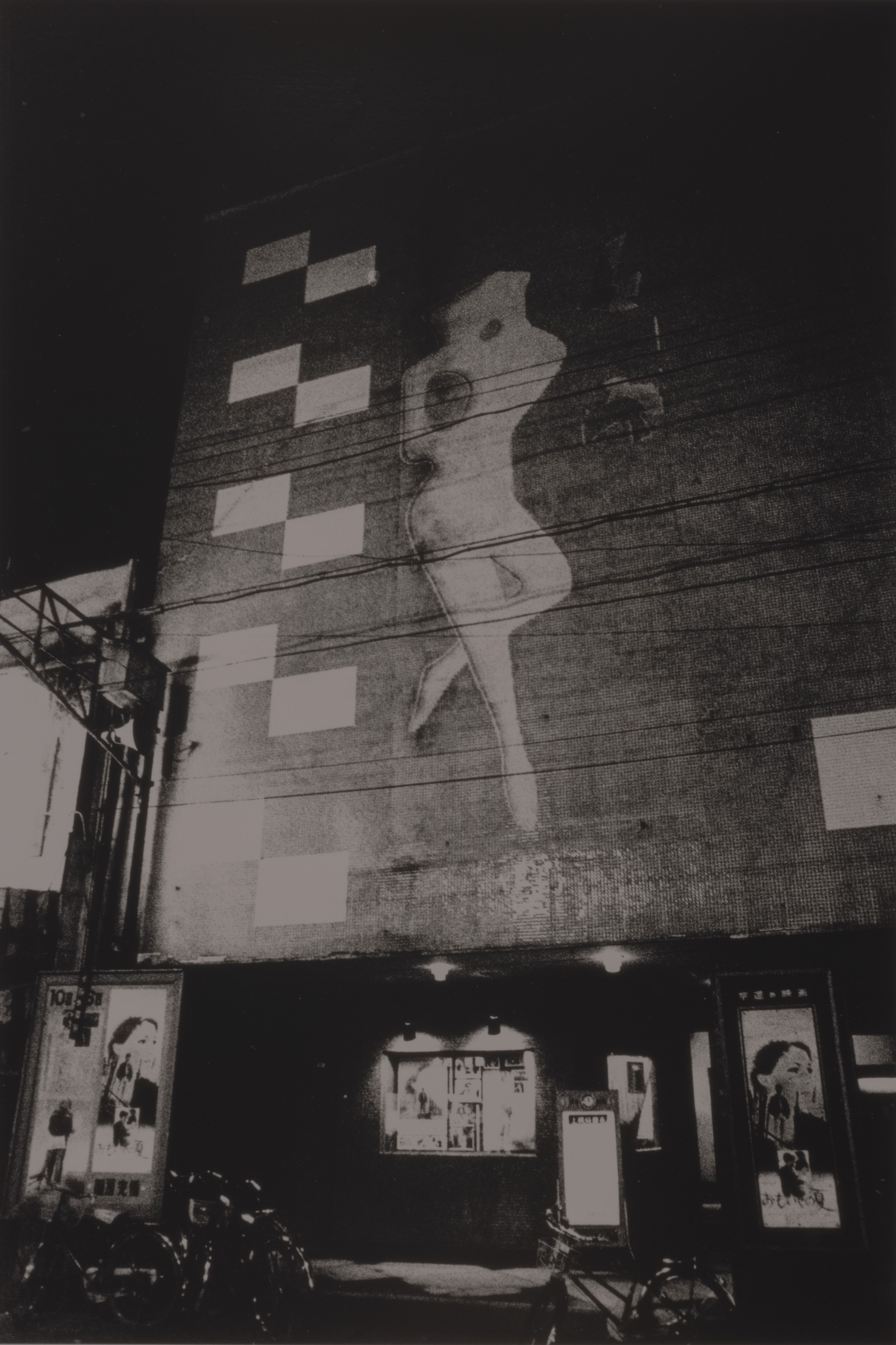

Hiroko Maruyama — To be honest, on the opening reception day, I visited the Alison Bradley Projects gallery without knowing whose exhibition was being held there. As I looked at the artworks displayed in the gallery, I thought, "These photos resemble those from Japan's Provoke era." However, the more I looked, the more I felt that there was something completely different about them.

Upon reading the exhibition description, I learned that the artist is a Japanese photographer who graduated from the Tokyo College of Photography [now Tokyo Visual Arts] in 1969 and has been active ever since. The fact that these photos were taken from a female perspective, which was not often seen in the photography of that era, piqued my interest greatly. Fortunately, I had the chance to meet you in person at your exhibition, and I feel very honored to have had this opportunity.

In the 1990s, movements of female photographers emerged in Japan, but in the 1970s, it was an era when photography was openly regarded as the least suitable profession for women.

The Girly Photography movement emerged in Japan in the 1990s partly because lightweight and compact cameras were introduced during that era.

Right. This camera [Nikon F3 single-lens reflex 35 mm camera] weighs over a kilogram.

How did that first camera come into your life?

Growing up, my father was into photography as a hobby. Our house had an environment where several cameras were lined up on top of the dresser. He had motion film cameras like 8 mm and 9.5 mm back then. I still have footage he shot with those formats. With cameras always around, taking photos didn't feel like a big deal to me.

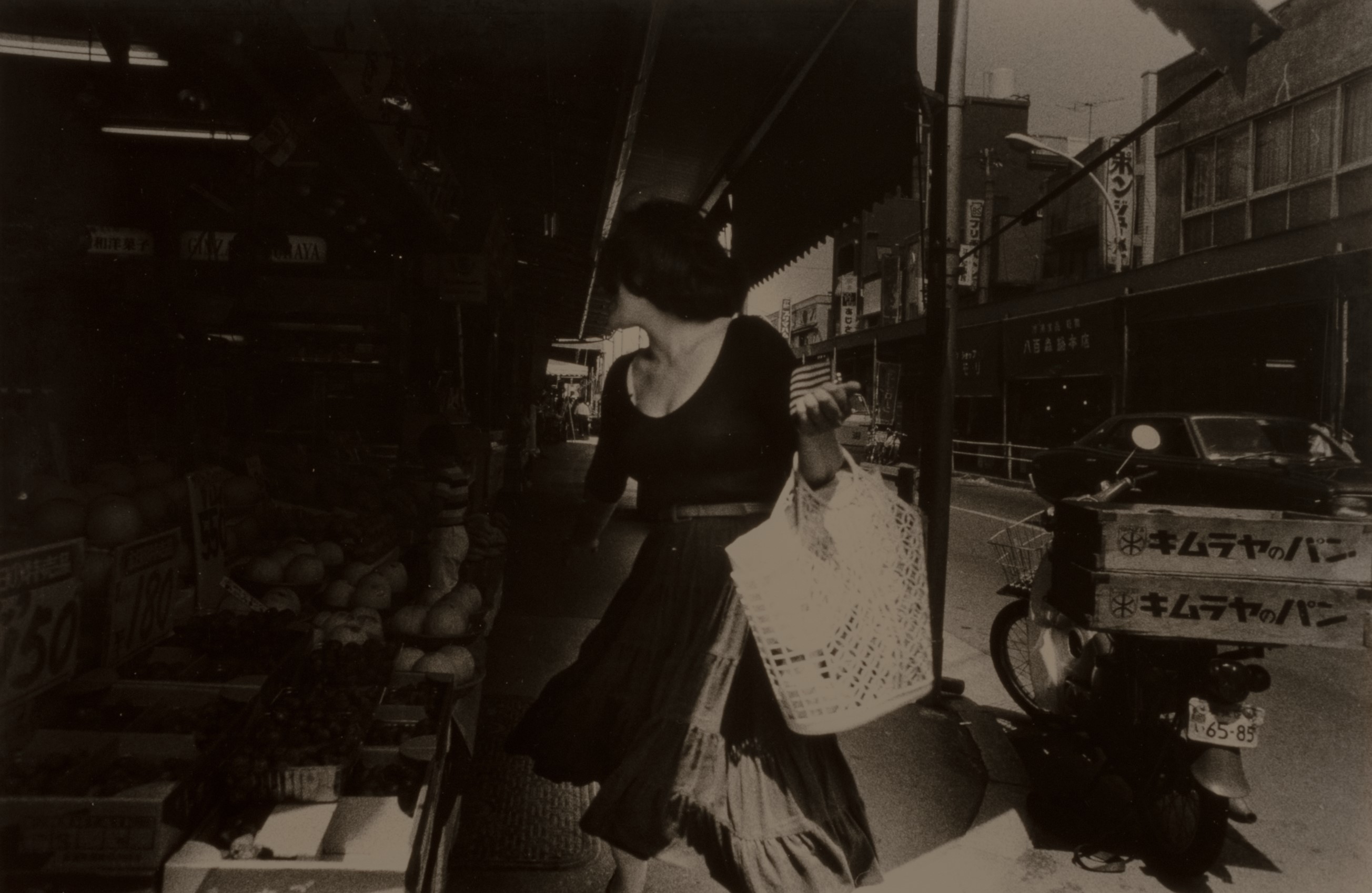

What kind of moments do you usually capture with your camera?

It's about encounters, you know, between the subject and yourself.

All the experiences you’ve had since you were born, including the ones you have forgotten. It is through these experiences that you’ve become who you are. Like when that version of yourself meets the world, you know? When you see someone's profile and find a nice angle or something. When the light hits them just right, without even thinking — you feel it and capture it. Those encounters are shaped by what you have cultivated, and you shoot with your own intention.

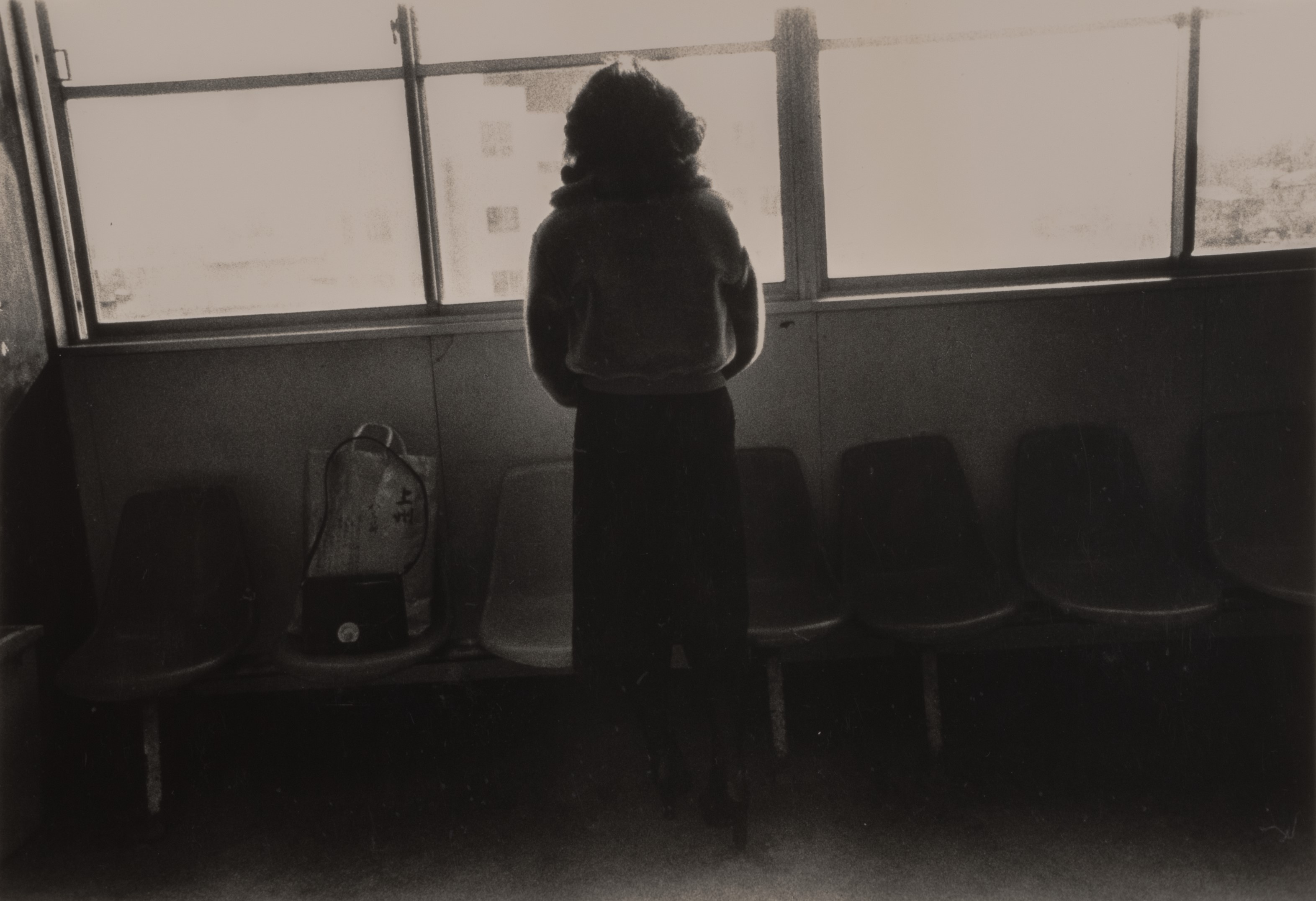

Your works often feature photos taken during your travels. Do you find more encounters as you travel around?

When you're traveling, you completely forget about any ties or obligations, right? Because you're only focused on exploring a new world — I think I enjoy that sensation. I frequently set off on journeys, work part-time to save money, then travel again, take photos, print them, bring them to the editorial offices of photography magazines, get them published, and then use the fees I receive to travel once more. It's a cycle.

In this exhibition, I'm also displaying magazines from that time that featured my work. About 90% of my photography trips are solo endeavors. Photography is something I do intensely on my own.

Smart. I respect you for how you've already set up this whole organic cycle within society, even though you started on your own.

Thank you. But back then, I was just a girl, you know? I nervously cold-called the magazine Camera Mainichi, saying, "I'd like you to see my photos." Then they said, "Come in such and such day at such and such time." I brought my prints, and the editor-in-chief flipped through them like shuffling cards. They would say, "We'll keep your work," and then I would hear back from them when my work was decided to publish. I continued in this manner.

Editors like Syoji Yamagishi, the editor-in-chief of Camera Mainichi, and Mr.Kōno, who was the editor-in-chief of Nippon Camera, were instrumental in understanding my photography. Their conformations affirmed my sensibility of capturing my idea of "encounters."

I think their support was crucial. Mr. Yamagishi was one of the top editors in Japan and was known for discovering photographers like Daido Moriyama and Kishin Shinoyama.

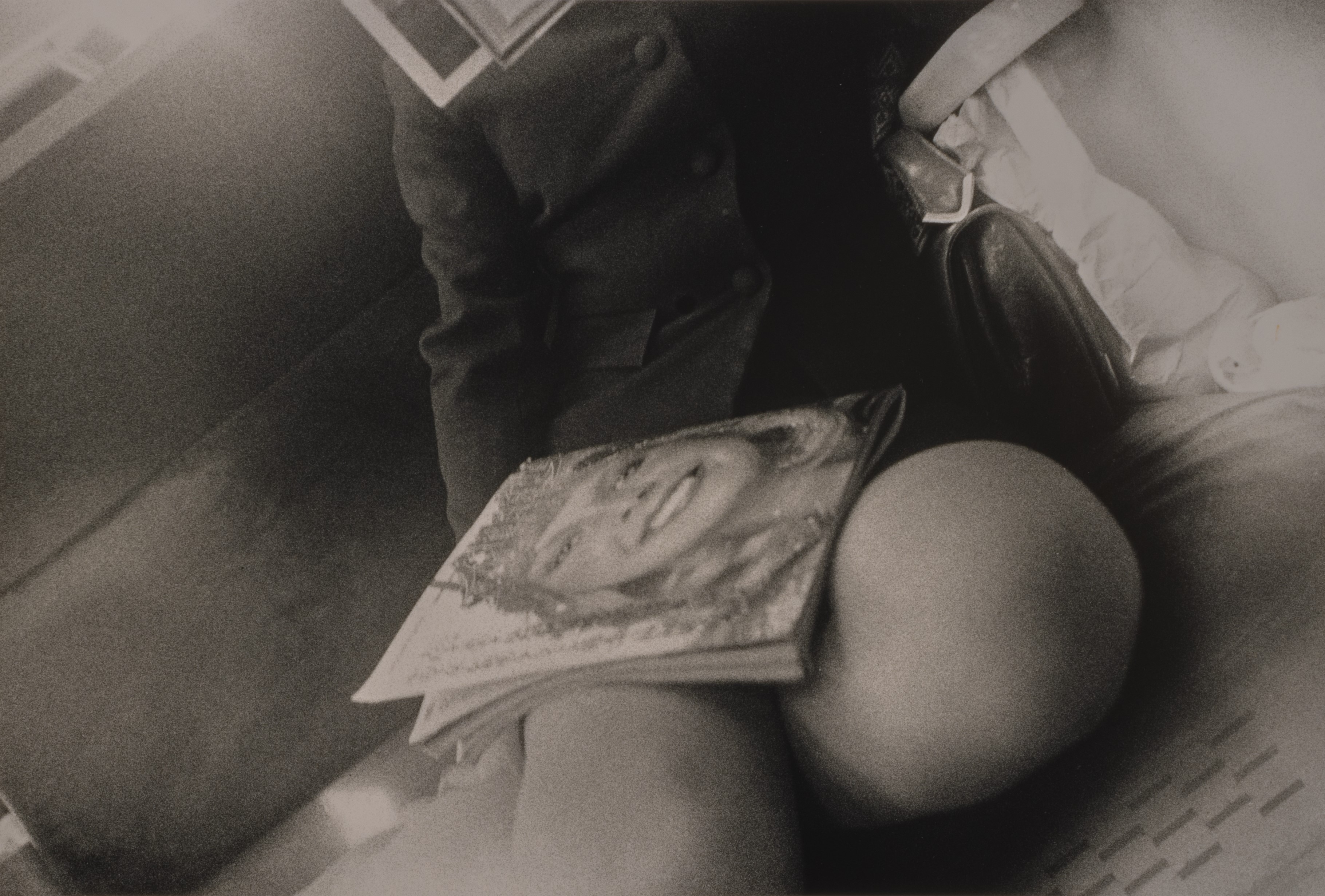

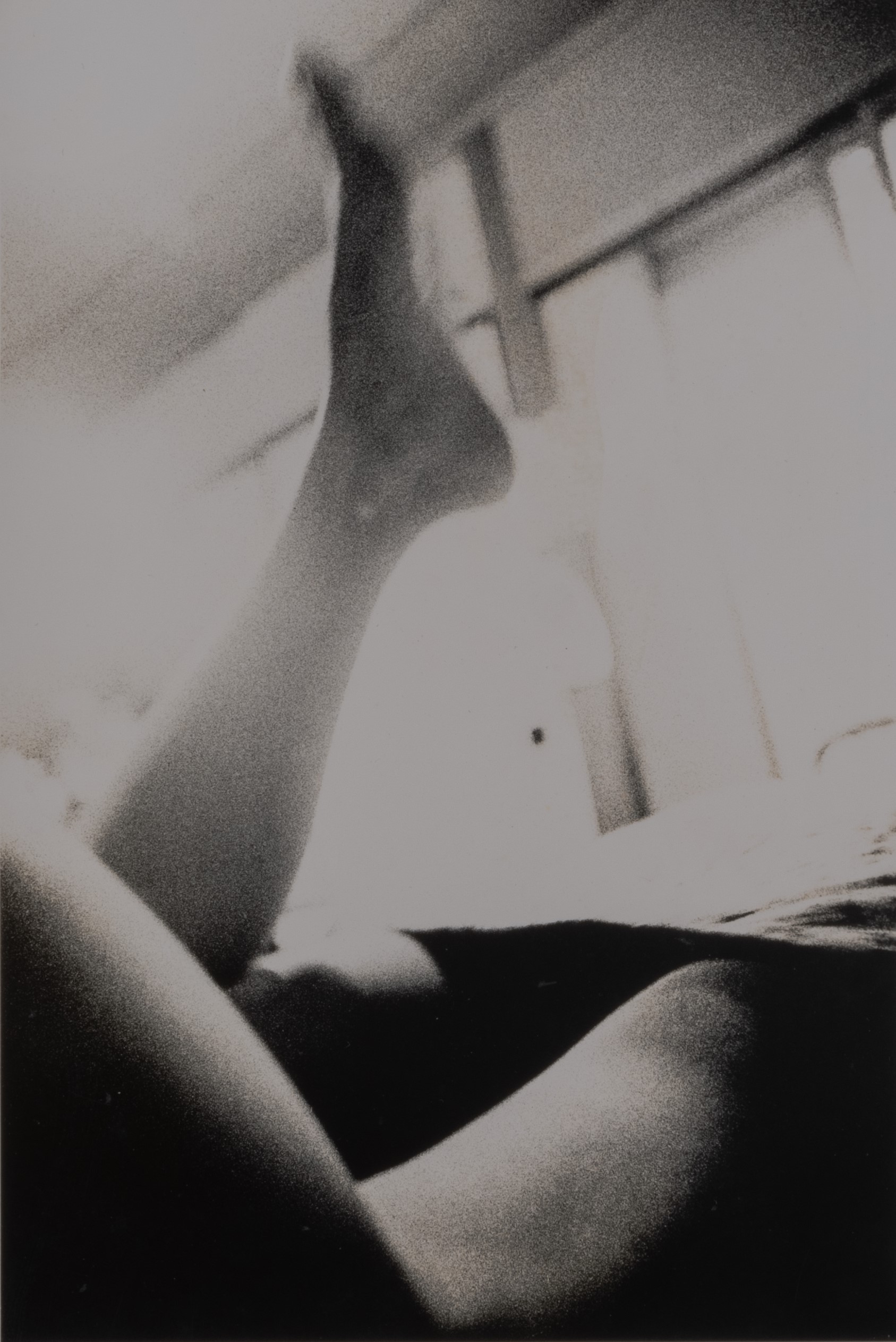

Kittenish... (2015)

I saw the artwork series Neko ga ... (Kittenish ... ), which was first unveiled on the pages of Nippon Camera Magazine in 1970. I found the photographs to have a rough texture and realized the image depicted women photographed at close range.

What struck me was the perspective, which was completely different from what is known as the so-called Shi-Syashin movement of the 1970s in Japan.

When I thought about why, I realized that I didn't sense a male gaze in this photograph. As the title suggests, the image felt like it had the perspective of a cat, in a room looking at the subject, with the shutter clicking every time the cat blinked. Your exhibition was a pleasant encounter, and I am glad that my preconceived notions of Shi-syashin-era photographers that I had before seeing your work have been removed.

Have you heard of the 35mm half-size camera? It's called the Olympus Pen Half Frame. You can take about 70 shots with 35 mm film. That's why the texture looks even rougher.

The editor-in-chief of Camera Mainichi, Mr. Shoji Yamagishi called me and said they were going to feature four or five female photographers. They needed some photos. I thought about bringing some travel photos, but then I thought it might not be that interesting. Since a friend happened to be visiting me, I spent two or three hours snapping away and brought those instead.

The editor-in-chief saw my series Neko ga ... (Kittenish ... ), and his first words were, "Tamiko Nishimura has brought back some naughty photos."

Since I had been showing mainly travel photos, I don't think he expected me to come back with such a series.

Haha. I like the series.

Thank you. Since I was short on time until the deadline, I shot the photos, developed and printed them in the darkroom immediately, and then took them to the editorial office.

I use Kodak Tri-X film, and I still develop the film myself in the darkroom. While I sometimes shoot with color film, I've been using Tri-X film for fifty years when shooting in black and white.

Why do you prefer using Tri-X film?

I like this film because it has a strong contrast between black and white.

I see. I've heard that you use high-temperature development and long-exposure techniques to enhance the contrast in your images. This film is an indispensable element in your artistic expression, isn't it? What's the story behind this exhibition? How did it come about?

Alison, the gallerist at Alison Bradley Projects gallery, reached out to me after seeing my first photo book, Shikishima.

I was 23 when I published my first book, and I didn't have much knowledge about promoting my work, so there wasn't much response at the time. It's only after some time has passed that I feel Shikishima has been appreciated.

My Journey (Ryojin) (2018)

My Journey II. (1968 - 1989) (2020), My Journey III (1993 - 2022) (2022)

You worked part-time for a short period with Kōji Taki during the early stages of your career, between 1969 and 1970, and regularly assisted in the darkroom shared by influential Provoke members Daido Moriyama and Takuma Nakahira. While your involvement is sometimes discussed in the context of the Provoke movement, I strongly sense the pursuit of your projects through your works and in our interview at this time.

I've simply continued taking photographs on my own for a long time without getting involved in the photography industry per se. Egotism, or similar traits, are endless, and when they creep in, they manifest even in photography. I've avoided all that because I don't want to feel any of it, so I've been doing it on my own. It's still the same today. As I see it, humans are creatures that don't change easily.

Many visitors attended your exhibition’s opening reception. How was the audience for you in New York? Did you have direct conversations with them, and were there any words or reactions that left an impression?

When asked about my worldview, I found myself thinking, "worldview, huh?"

It was quite intriguing to be exposed to various perspectives, and I enjoyed seeing everyone's reactions. I couldn't help but feel that maybe in America if you don't explain things in words, they won't get across. That aspect felt very appealing to me. I've wanted to go to New York since the 1970s, but over time, it became a place that seemed less accessible, as my desire grew stronger. I feel truly fortunate and moved to have the opportunity to share my work with everyone in New York, thanks to meeting Alison and the connections made. Yesterday, I saw the city of New York from the Empire State Building.

I know, I heard from your friend Kazuhiro Yamaji of Flying Books [bookstore in Tokyo] about that this morning. I asked him if the rooftop of the Empire State Building gives the impression of strong winds. Kazuhiro said, “She was taking photos and calmly changing films on the windy rooftop.”

You took a lot of pictures on this trip, and I'd be happy to have the opportunity to see them soon.

I'm planning to develop them as soon as I get back [home in Japan].

Could I ask what you always bring with you when you travel, as a final question?

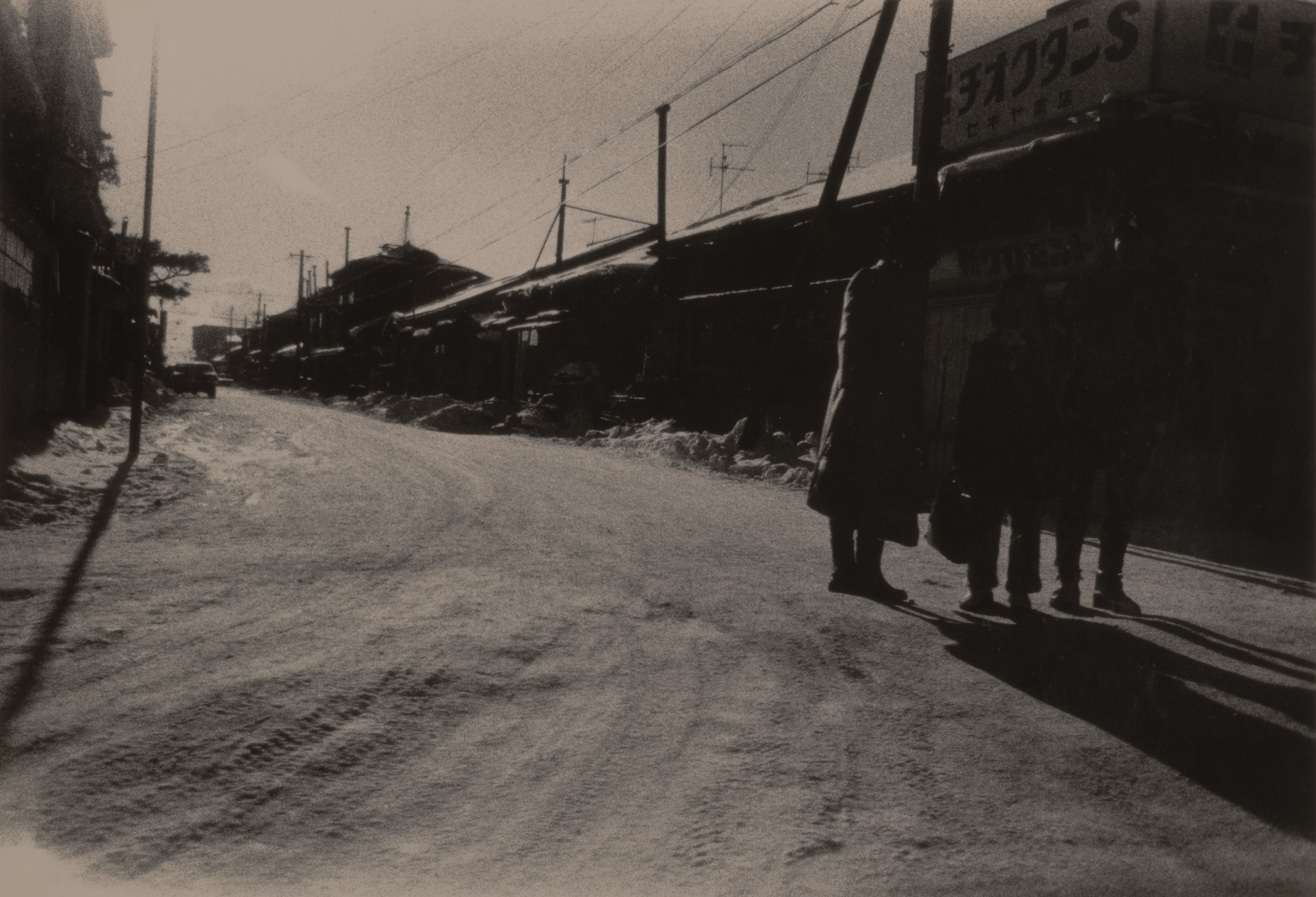

I'm from Tokyo, but when I was around 20 years old, I loved traveling to the northern regions like Aomori and Hokkaido. I always brought a paperback of Dazai Osamu's Tsugaru with me. At that time, I used to travel by overnight train, departing from Ueno Station at night and arriving in Aomori by morning.

There are songs in Japan with lyrics like that, right?

Yes, you're right. The songs were written long after my travels, but it felt like that back then. I remember reading that book on the sleeper train to Aomori. After finishing it, I'd leave the paperback at the ryokan wherever I went. But I always wanted to bring the same book on the next trip, so I ended up buying five or six copies of Tsugaru in paperback.

What did you like about Dazai Osamu's Tsugaru?

Dazai Osamu was an author who passed away the year I was born, but in Tsugaru, I felt he depicted the Aomori I knew. For instance, about Cape Tappi, there's a line in Tsugaru that goes, "I thought I was sticking my head into a chicken coop, but it turned out to be Cape Tappi."

When I first visited Cape Tappi, I had exactly that sensation of sticking my head into a chicken coop. There were still such familiar sensations there. Japan changed a lot in the 1970s and 1980s, becoming modernized. Before the 1970s, throughout Japan, there was still a connection [culturally] to the eras of Edo, Meiji, Taisho, and Showa.

Everything started changing in Japan, and wherever you went, you'd see the same landscapes and sceneries once you got off the train station. This prompted me to start traveling abroad.

I lived in Mitaka, Tokyo, for eight years. I commuted daily from the station to my home via Tamagawa Josui. Dazai Osamu also lived in Mitaka, didn't he? There was a Dazai Osamu study group in Mitaka, and I participated in the group as well.

When you look at someone's bookshelf, you can somehow understand their personality, I think. And hearing this story made me feel like I got to know you a little better. Did you release a new book in 2022?

Yes, I have been taking photographs for about 50 years, and I have compiled them into a work of art [My Journey III. 1993-2022, published by Zen Foto Gallery, 2022.] I have many unpublished photographs, most of which were taken in the 1970s, and I plan to publish them this year.

Journeys is on view at Alison Bradley Projects, 526 W 26th St #814, New York, NY 10001, through June 29, 2024.

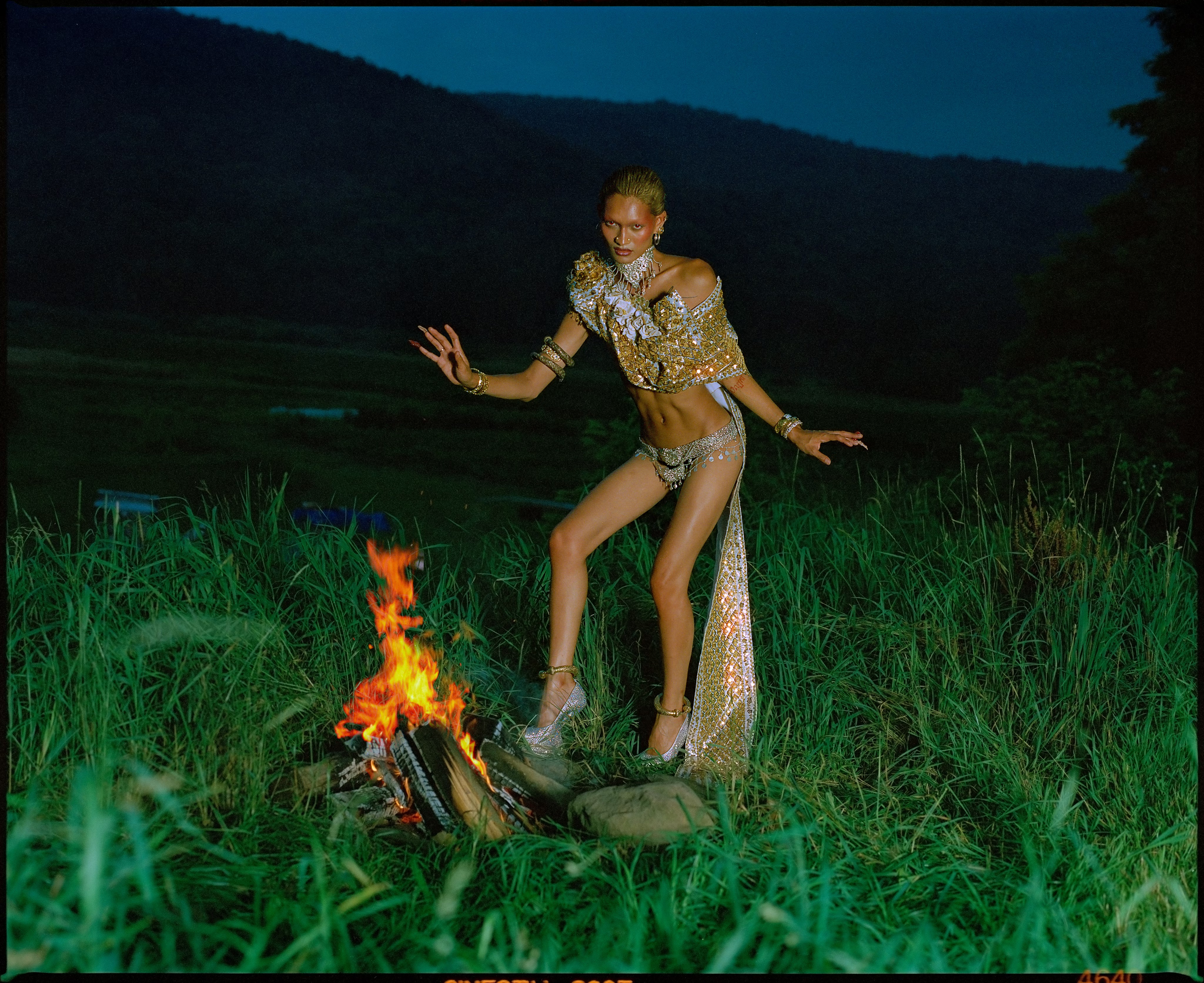

The exhibition traces a journey toward personal transformation, exploring themes of heartbreak and rediscovery of self-love through the lens of the seven deadly sins: wrath, gluttony, greed, lust, envy, sloth and pride. The seven garments took over two years to complete, and each has its own poem, intended to breath life into the strands and evoke the essence of each sin. Of the project as a whole, Sinn explains that "'NC7DS' is a collection of garments as well as unsent love letters to a love [she] lost. The manipulation of fabrics mirrors the psychological pull and tug of being in love and losing it. The film follows a journey in rediscovering self love through the stages of each deadly sin to reach one’s higher form."

We caught up with Sinn following the launch. We discussed sharing this project with the world for the first time and in this capacity, her Cambodian ancestry, and her experiences with love and loss. She gave us the best description of the Angelito Collective we've heard yet: ... the one stop family shop for cunt shit. Period.

What aspect of the exhibition were you most excited about attendees witnessing/interacting with?

I’ve waited very long time for this to be released. For my voice to be heard. I honestly can’t even narrow it down into a list because there are so many aspects of the gallery that are going to shake girls up.

Firstly, more than anything in the world, besides shoes, designing is my number one true love. It is a piece of me that I rarely share with the world. The girls know I make garments but most of the time people aren’t aware of it. Actually, the outfits that the girls are wearing to the gallery are an extension of the exhibition. A play on a funeral of the old me to signify I’m onto another chapter in my life. Also, the looks are sustainably made from vintage leather coats and pants I’ve thrifted. Save the world but do it cunt.

Secondly, I’m a proud Cambodian. My culture is something I hold close and weave it into everything I do. I am Cambodian before I am anything else. Shoutout to my mother for keeping it alive and I owe my taste and references to the karaoke videos she used to play of Khmer woman dancing in the most beautiful looks inspiring me to do so with this collection.

Thirdly, for everyone to experience NC7DS in its entirety. It been shown in Miami, LA, and Philly but it's been like a set of photos or just one garment. To be able to see every poem against every look with the campaign photo next to it is gonna be wild. These love letters are a piece of my heart and breathe life into the garments which makes it feel like the exhibition is alive.

What I’m most excited to show everyone is that the Angelitos don’t just throw parties and look cute. We actually have a deep love for creating art, telling authentic stores of trans love and making sure we’re being heard. We literally do it all. The Angelito Collective is the one stop family shop for cunt shit. Period.

And you already have plans to feature the film somewhere else after this right?

We’re in the talks of placing it in a few spaces. The next place would be at “Junto” gallery exhibition on Govener’s Island and touching down in Toronto this summer. She’s gonna go on tour for sure! Bus, club, another club...

What is your experience debuting work that traverses mediums and while also deeply personal throughout is influenced by various perspectives — the garments, poems, photographs, and film being created independently?

Honestly, everything just came together the way it was intended. We were planning to shoot the collection on my birthday last year. We only were going to feature the images, garments and poems. The night before we left to shoot; Jordan, Ramie, and Demi came up with a screenplay based on the poems to shoot on the farm. Having a film aspect really turned NC7DS into its own entity. It was the last piece of the puzzle to tell the story in such a perfect way, through the lens of the ones that were with me through this journey of heartbreak and a whole bunch of other obstacles.

For me, the attentiveness that [Angelito] had to turn this up a notch really put a new view on how I view my peers. Ranxelle was there styling, who styled me for our first film, “Cion Mami.” Kam + Ramie shooting me so specifically and how they wanted everything captured. The care that went into this, I cannot thank them enough. Mind you, we only had 3 days to drive upstate and shoot this. This was the best gift I could’ve asked for.

Sinn, are you catholic or were you raised as such (I’m curious as to where the relationship to the seven deadly sins came from)?

No im not catholic. I came up in a Christian background but most of my family is Buddhist. So I was always surrounded by different views of life and death.

My name is Sinnveasna. Sinn is my moms maidens name and ‘veasna’ is my dads second name which means destiny. Basically it’s kind of written in the stars. A destiny of Sinn. I’ve always had a fascination on mythology, Dante’s inferno and ancient rules that no one knows where they came from.

In the beginning, it seemed so campy to do a Seven Deadly Sins collection. I found it hilarious. But now it’s become my salvation and something so serious. NC7DS comes from a long line of lost lovers. Romantically and platonic. The poems/ letters started from sending love letters to a lover and when I asked him if he ever got my letters, he said he never received them. This was also around the time, I started coming into my transness and trying to understand love whilst trying to understand yourself is a wild ride.

So I began just writing poems/letters and never sending them to people that began walking out my life in a sense to hash out any residual feelings because I’m not much of a talker. And the relationships I placed myself in, I felt as though my words didn’t matter. Seeing them on paper was easier than seeing them rejected when the words left my mouth.

It’s crazy because throughout this process, the poems began writing themselves. For example 006PRIDE was the last poem I wrote; it’s all about integrity and thinking highly of yourself.

I was at a party and I kept dreaming about someone for a few nights. Then, he shows up to the party my friend was hosting at and I see him across the room. We didn’t speak or anything but I’m like this was what I need to finish this off. I thank him for setting me free from whatever the fuck that was.

now you stand before me

peeking under a glossy red light

a stranger who knew the anatomy of my love language

…….

no longer can I feel pain

Ive been set free

finally

Sewing and writing became my therapy. Breathing energy into each stitch I was doing turned my feelings into something I can hold. And sooner or later, I had a seven-look collection, a lighter conscious, TRANS, and super fucking hot. LOL.

Find more info here.

Since her first presentation at The Kitchen in 1990 as part of the New Works, First Runs screening, Leeson has continually contributed to the institution’s programming, hosting TV Dinner No. 3 in 1999 — showcasing photographs from her Phantom Limb series and clips from her film Conceiving Ada starring Tilda Swinton — and participating in The Kitchen's 2019 Editions Portfolio. Desire Inc., currently on view in The Kitchen’s Video Viewing Room (and online through June 16, 2024), highlights four of Hershman Leeson’s groundbreaking works: Commercials for 'Forming a Sculpture Drama in Manhattan' (1974), A Commercial for Myself (1978), Test Patterns (1979), and Desire Inc. (1990).

Tonight, The Kitchen honors Hershman Leeson during its annual Spring Gala, recognizing her alongside visionary patrons Bernard I. Lumpkin and Carmine D. Boccuzzi, and the legendary composer Max Roach (1924-2007). Ahead of the Gala, Hershman Leeson joined The Kitchen’s Senior Curator Robyn Farrell to discuss television, the eclipsing rise of the internet, working across mediums, and finding resonance with an audience more attuned to the nature of her work.

Lynn Hershman Leeson, The Electronic Diaries, 1984–2019. C. Hotwire Production LLC.

Courtesy of Bridget Donahue Gallery, NYC and Altman Siegal Gallery, San Francisco.

Robyn Farrell — Lynn, I am thrilled to have the chance to speak with you, on the occasion of The Kitchen’s (TK) launch of your Video Viewing Room (VVR) program. We have had the distinct pleasure of collaborating with you on a number of occasions including the New Works, First Runs screenings in 1990, as the host of TV Dinner No. 3 in 1999, and as a contributor to the 2019 Editions Portfolio. We look forward to celebrating this history by honoring you at TK’s spring gala on May 22.

Your VVR program centers around four works (Commercials for Forming a Sculpture Drama in Manhattan, 1974, A Commercial for Myself, 1978, Test Patterns, 1979, and Desire Inc., 1988) that subvert the form and context of the TV commercial. You have described your TV commercial works as “electronic haiku.” Can you talk about what this means and what first attracted you to the medium of television as a means of creative production and reach?

Lynn Hershman Leeson — I believe every format of communication is a means of creative production, even if there is no history of it. At the time, television had the potential to reach far more viewers than an alternative space or museum. And television featured commercials, often ones that were extremely creative. But they are by definition succinct, and the messages need to be creatively reduced to the essence — hence "haiku". Commercials are always short and need their message to smack reality immediately. They are also delivered electronically (or were in those days, prior to digital haiku), so that's what the term came from.

RF — Will this be the first time your commercial works are shown online? Do you see this mode of broadcast (via the internet) as significantly different from their original circulation on public television?

LHL — I have shown my works before whenever I could, often online. The internet has a broader reach and relies less on the "framing of a program" but the consequences and context outline of what will be seen and who made it.

RF — The latest work included in TK’s VVR program is Desire Inc. made in 1990. By this point your work had already explored audience engagement and technological interface beyond the traditional viewing modes of television. Lorna, [earliest interactive LaserDisc, (1979-84)], for example, is the first thing that comes to mind, and how the physicality, tactility, and conceptual notion of “the remote” itself is central to your work.

Lynn Hershman Leeson, Still from Desire Inc., 1990.

Courtesy and copyright by Hotwire Productions, LLC.

LHL — It kind of mirrors what you're watching, and I wanted to create a performance space that imitated the video space. Somebody engaging with the work had to simulate what was happening by using a remote rather than just turning the switch off.

RF — In your essay, “ART-IFICIAL SUB-VERSIONS, INTER-ACTION, AND THE NEW REALITY” (1993), you outline key technologies (telephone, automobile, television, and computer) that have disrupted linear structures of time and space. These watershed moments created models for “disengaged intimacy” as you call it, a term — in both concept and meaning — that serves as a mechanical prosthesis that extends human reach. Can you talk about how technology has informed your film and video work over time?

LHL — Wow, that is quite a question. I live in the bay area where a lot of this kind of technology was generated. It was important to me to use the technology of the time to talk about issues of the time. So whenever I learned of a new technology being released I designed a project that exploited it. There are a lot of works from commercials, to websites, to video and films, and each used whatever technologies were new or hadn't yet been used, whether it was 24k or virtual sets and everything in between.

RF — You engage the idea of mechanical prosthesis further in your Phantom Limbs series (1985-1987) which was included in the group of works you presented at The Kitchen's TV Dinner in February 1999 (The Kitchen’s TV Dinners ran from 1998–2004). The black and white collages merge female bodies with objects such as cameras, clocks, and televisions. As seen with your commercial broadcasts, this anthropomorphic series questions the seduction of media and surveillance systems that are embedded in our society. The anthropomorphic images presage contemporary notions of identity, vanity, and the female body, as filtered through ever evolving modes of technology. Can you share the impulse behind this series?

LHL — I integrated those ideas in the hope of making people aware how surveillance shifts not only how we see but what we see. Both are affected.

RF — You have said your early life experience with technology and the body informed your practice. Your Breathing Machines (1965-1967) being the earliest example both in your body of work, and one of the first sound sculptures in contemporary art. Can you speak more about the ways in which new technologies affected your work? How you pursued them throughout your career, and if there's a particular moment that stood out to you as a new mode of communication within your work.

LHL — I can't point to one specific one. Certainly Photoshop and PowerPoint, but really every new technology had things you could learn from and adapt work to. But I can't say that one in particular overshadowed the others.

RF — Photoshop in particular stands out to me, especially as it relates to the Phantom Limb series: You physically manipulated these works – cut and paste, right?

LHL — Yes.

Lynn Hershman Leeson, Seduction (Phantom Limb) Series, 1988. Copyright of the artist,

courtesy of Bridget Donahue Gallery, NYC and Altman Siegal Gallery, San Francisco.

RF — This was second nature in the eighties but with the advent of Photoshop, it not only changed the duration by which one might work with a collaged image, but also shifted the engagement with material because you're no longer physically working with different types of paper, [one] was just working on a [computer] screen. I am curious, do you find ways to replace that tactile experience of hand to paper? Is working with paper and drawing still a part of your process despite the fact that it's become more technologically involved over the years?

LHL — Yeah, I do a lot of drawings and collages. So in that sense I still have the same experience, but for certain kinds of work, you can't do that or it's inappropriate to even think about doing that. So really it expands the possibilities of how one approaches work.

RF — I am similarly interested in the role of writing in your process. I first became aware of your criticism when I read Reflections on the Electric Mirror (1978). You've published numerous texts since the 1970s, how does writing factor into your visual work? Is it a parallel practice or interwoven within everything you do?

LHL — It's not parallel at all, but it is interwoven. The reason I started writing about my work was because nobody understood it, so I had to explain it. I had to do these little pamphlets to tell people why I did what I did because they didn't understand the technology of it. And if you want to make a film, you have to write scripts or have some other form to figure out what you're going to do. So the writing I think is a supplement to the other art projects, but it's essential to it. I rarely write just to write, although a book is going to be coming out soon that has a lot of my writing in it.

RF — TK’s TV Dinner series captured the ethos and values central to The Kitchen's mission. We are honored to collaborate with you again and bring that history back into light and celebrate it as part of our collective past in this present moment. When you hosted TV Dinner [No. 3], you shared slides and excerpts of your work, including Conceiving Ada (1997). Was that kind of program format unique to you at the time? Or just one example of a creative community gathering over food and cultural discussion.

LHL — I think people didn't know what they were doing, so they were looking for any kind of way to communicate and show work because there wasn't any fixed format.

RF — Your work now has incredible reach. What are your thoughts about your films now being available to stream on the Criterion Channel?

LHL — Well, I think it's great because all kinds of people can look at it, whether they know my work or not. It just makes access more available and expands the reach of people finding it.

RF — Yes, and I am glad you mentioned access because, to me, access brings everything back to these commercial works. I know that we touched on their dual function — both promoting and presenting — but they also had a didactic function as well. Access to a mass audience via broadcast is something that enticed many artists into experimenting with television as a site of production and distribution in the late 20th century. You’ve been a pioneer thinking about the ways in which your work can flow through the cultural landscape, whether through exhibitions in institutions or galleries, or online. You mentioned that your writing began as a mode of access to provide information about your work. So is it fair to say that access across forms of media and interpretation has been a driving consideration in your work?

LHL — Yeah, because people rarely recognized my work as art. In fact, the idea not art came I think in 1968 when I tried to show sound at the University Art Museum and they closed my show. So I have spent probably 50 years trying to get my work seen because work that I was doing that I felt was the most crucial and the most important and the most current people didn't want to show because nobody had done it before, so they didn't recognize it as art. So that's been a problem all these years.

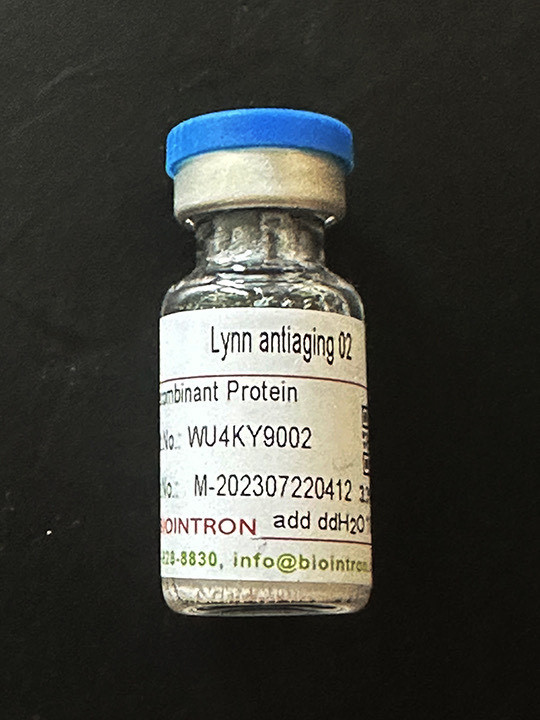

ANTI AGING VACCINE 2024, protein, animo acids plus related materials, 1" X 4" vial.

RF — Your recent exhibition at Bridget Donahue Gallery explores various meditations on the passage of time and the body, as chronicled through your work for the past five decades. The exhibition lays bare the prophetic lens of your practice that examines the influence of technology on human existence. Self-perception and self-reflection are long-running themes across your body of work. Has the idea of aging/anti-aging been an area of recent focus for you or something evolved over the course of your career?

LHL — I think it has always been part of what I think about because I was quite ill as a child and not expected to live past age 23. So I came to terms with death early, but aging itself and the process and effect of it creeped up on me, as it does everyone, and is a key part of not just contemporary thought but the products of our culture.

RF — For your new video Cyborgian Rhapsody: Immortality, 2023, you approached the script differently, by working with AI. Do you feel technology has evolved to a state where you have to adjust the way that you work when producing a film?

LHL — Because I said the premise was that the AI would write the script and I would've written a different script, and I think I would've written a better script, but I had to do it because that was what it was about. What would an AI have to say and what would their story be? A lot of people don't realize that I stayed out of the story making for that reason. That was part of the whole concept of why that video happened.