The Artist and the Cigar Box: Civil Pleasures

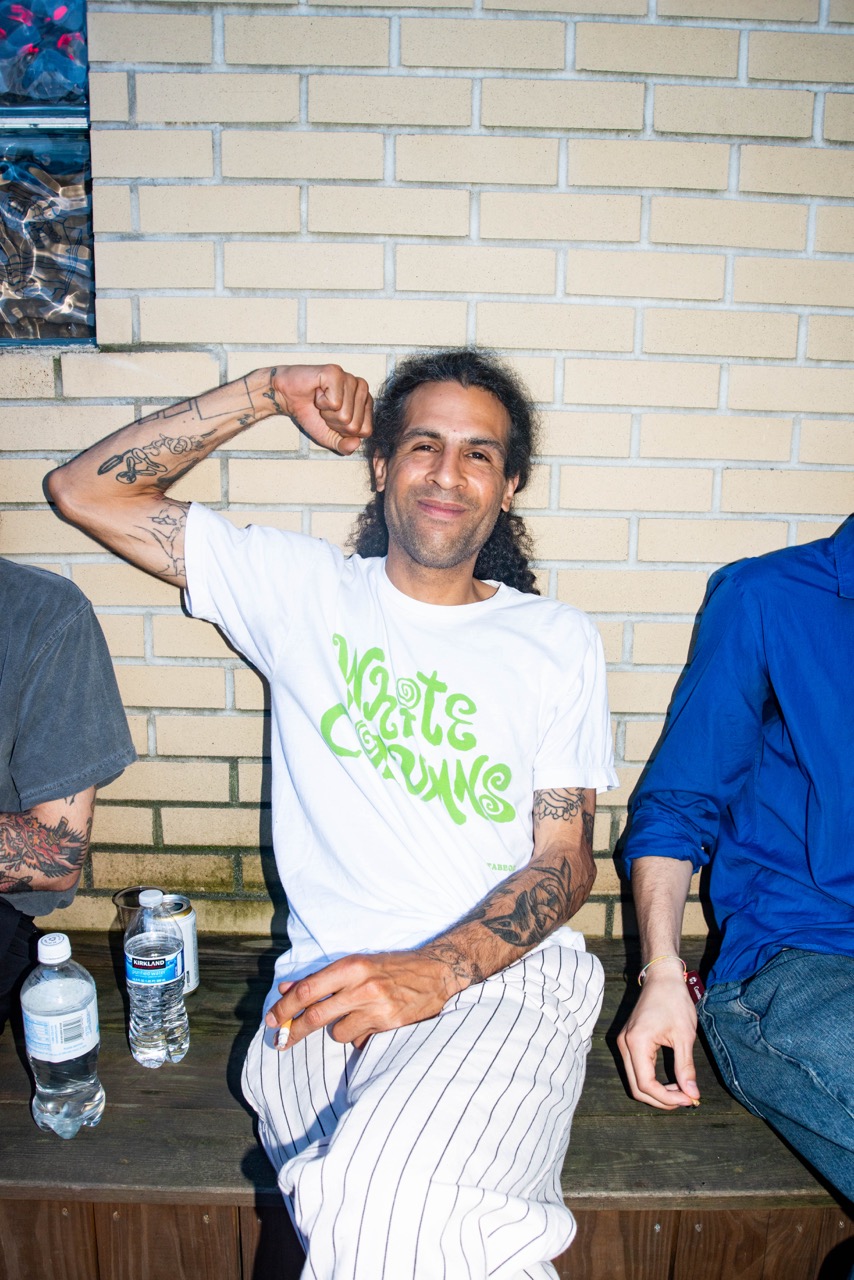

Check out photos from the opening night below and put your bids in here. The Artist and the Cigar Box online auction.

The Artist and the Cigar Box is on view online through June 30th.

Stay informed on our latest news!

Check out photos from the opening night below and put your bids in here. The Artist and the Cigar Box online auction.

The Artist and the Cigar Box is on view online through June 30th.

The Alexander Gallery is haunted by the phantoms of the past. I imagine curating a show in a space like this is equivalent to checking in at the Chelsea Hotel, hosting a party at CBGD (impossible, thank you wholesale), or ordering the Bacon Burger at JG Melon. It’s a New York time capsule, nostalgically self-indulgent, and rightly so.

When you inherit a legacy like this, it’s easy to fall into the trap of repetition. At times, the motive behind this repetition is that of pressure, a sense of honor, or frankly, fear — the anxiety about living up to whatever was created before your arrival; the feeling of stepping into shoes too big but wearing them anyway. Sure they might walk you down the same path, but that's precisely the problem. Thus, one needs more than a microdose of either confidence or naivete to escape the dead end.

Chris Lloyd, I Shall Cut Off My Eyelids To See Better, 2024.

Cristine Brache, Blue Mood, 2024.

“You’ve got to have a serious ego problem to own a gallery,” quipped Alexander, ticking off the qualities above. He has an unsanitized perception of himself as a tastemaker. Nevertheless, his indifference prods the question: does every artist embody this trait? Underneath the imposter-syndrome’s standing reservation, which resides in every other creative, hides a desire to be looked at, to be perceived. Is that egoism or is it a survival instinct?

The outcome of the ego is not what defends Spy Project’s arrival in New York. Perhaps it is the fact that Brooke Alexander is indeed Pietro Alexander’s uncle, but it’s also more than that. Truth is that the exhibition stands independently, removed from the pressure of legacy. With ease, the space’s saturated history presents both established and emerging artists. Rooms are filled with creatives united in nothing but their allied urge — “need” as Apple puts it — to leverage the relics of New York’s post industrial landscape and channel it into not only their practice, but into their way of life.

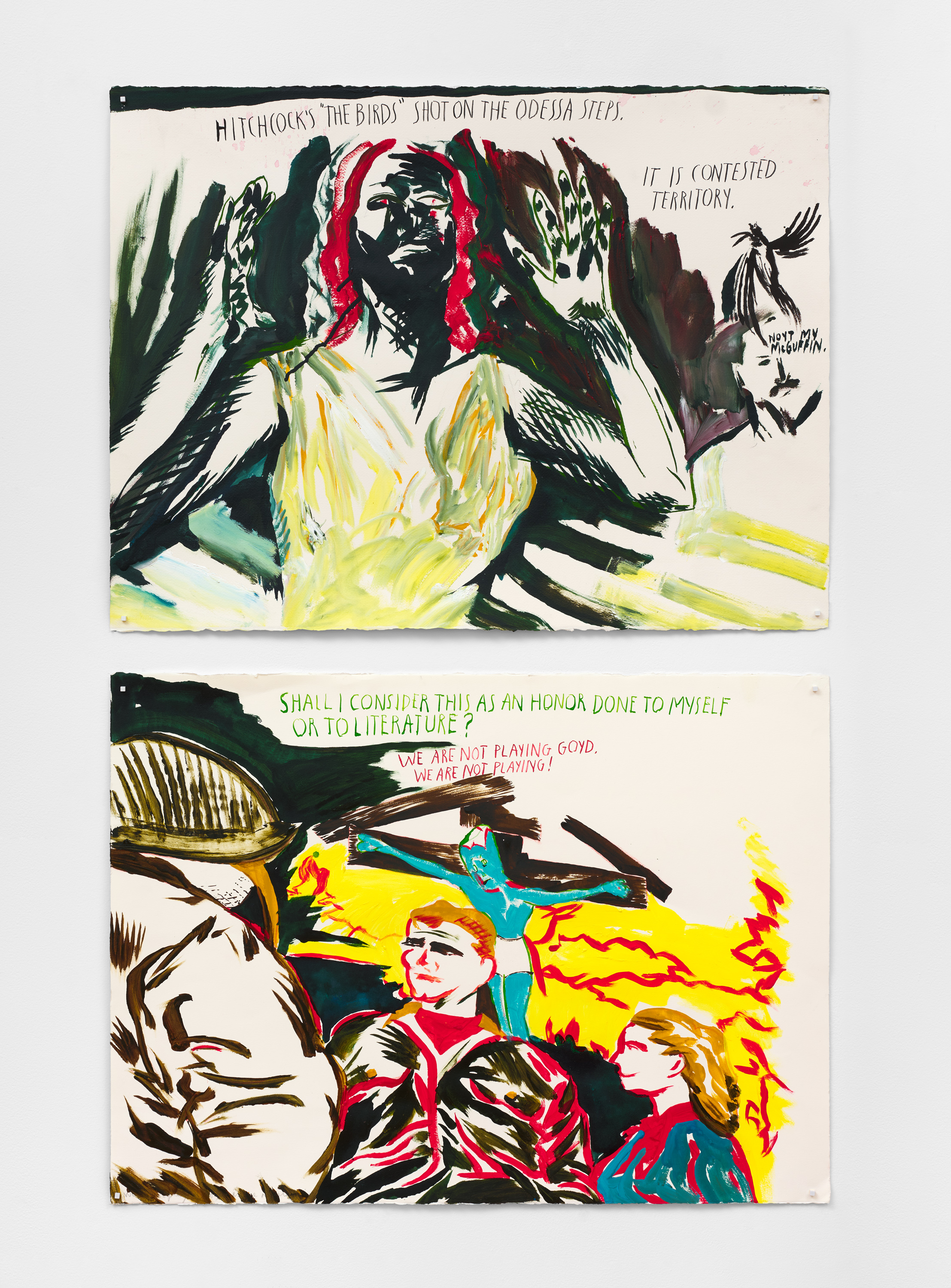

Raymond Pettibon, Untitled (Hitchcock’s “the birds”…), 2024. Untitled (Shall I consider…), 2024.

Katherine Auchterlonie, Feuillet-Beauchamp Notation of a Good Make-Out Session, 2023.

Kay Kasparhauser, Blood, 2024.

It feels like a family affair. The curation isn't trying to overcome some grand endeavour by suppressing the works under an artificial title. "Unrequited" is a title as blank as the gallery’s walls, granting them permission to tickle our thoughts again and again; (almost) all works are alike only in their differences — exception being the artist who sent in doubles, in which case the pieces aren’t neighboring, but placed at a screaming distance across the rooms, perhaps to provoke that very same tickling effect.

Textile collages by Alison Peery talk to Peter Alexander’s turn to velvet from 1984; Montana Simone’s pieces assert authority not only in scale but through their almost aggressive acquisition of steel while Kay Kasparhauser’s medium reads as hair, moss, and “Kay’s blood;”. Malik Al Maliki’s outlandish treatment of woodblocks tempers the violence within Raymond Perribon’s vocal acrylics, whereas within Sasha Filimonov’s panel — reminiscent of domestic Eastern European propaganda — the artist has installed a portable gun, which, when activated, is almost as arresting as the female figures concealed behind the thick layers of wax on Cristine Brache’s works. The effect quite literally blurs the line between dehumanizing and dream state.

Cristine Brache, Purple Bunnies, 2024.

Montana Simone, Choke Collar, 2024.

Sasha Filimonov, nightlight, 2024.

Unrequited is being at the library but only reading one page in each book. It’s scrolling Netflix but instead of watching one film, you pace through one trailer after the other. It's like being hungover at that brunch-buffet Sunday morning, suddenly finding yourself seated with a plate of croissants, bacon, bananas, strawberries, scramble eggs, yogurt, cream cheese, avocado, pancakes, ryebred, ham, turkey, Manchego, granola and roasted tomatoes…. But does it leave you overfed? Do you walk out feeling nauseous? A group show is always a slippery slope.

Spy Project’s New York debut isn’t mimicry as the mannequins at the flagship next door. It’s not imitating the legacy which it finds itself ensconced, nor is it posing for the sake of being seen. Unrequited sits you down for family dinner, where conversations traverse generations, opinions are opposing, and no one hesitates to voice their views.

Before I left the gallery on Wednesday afternoon, Apple pulled up the window to invite the neighbors smoking on the fire escape across the street to the opening the following evening. They looked like they’ve absolutely nothing in common yet there they were, making sense in one another.

Spy Projects, a contemporary art gallery in Los Angeles founded by Pietro Alexander in 2021, is temporarily visiting New York. The exhibition, Unrequited, will be on view through May 31st, 2024, at 59 Wooster Street.

Gal Schindler, Wishing Well, 2024. Courtesy of the artist.

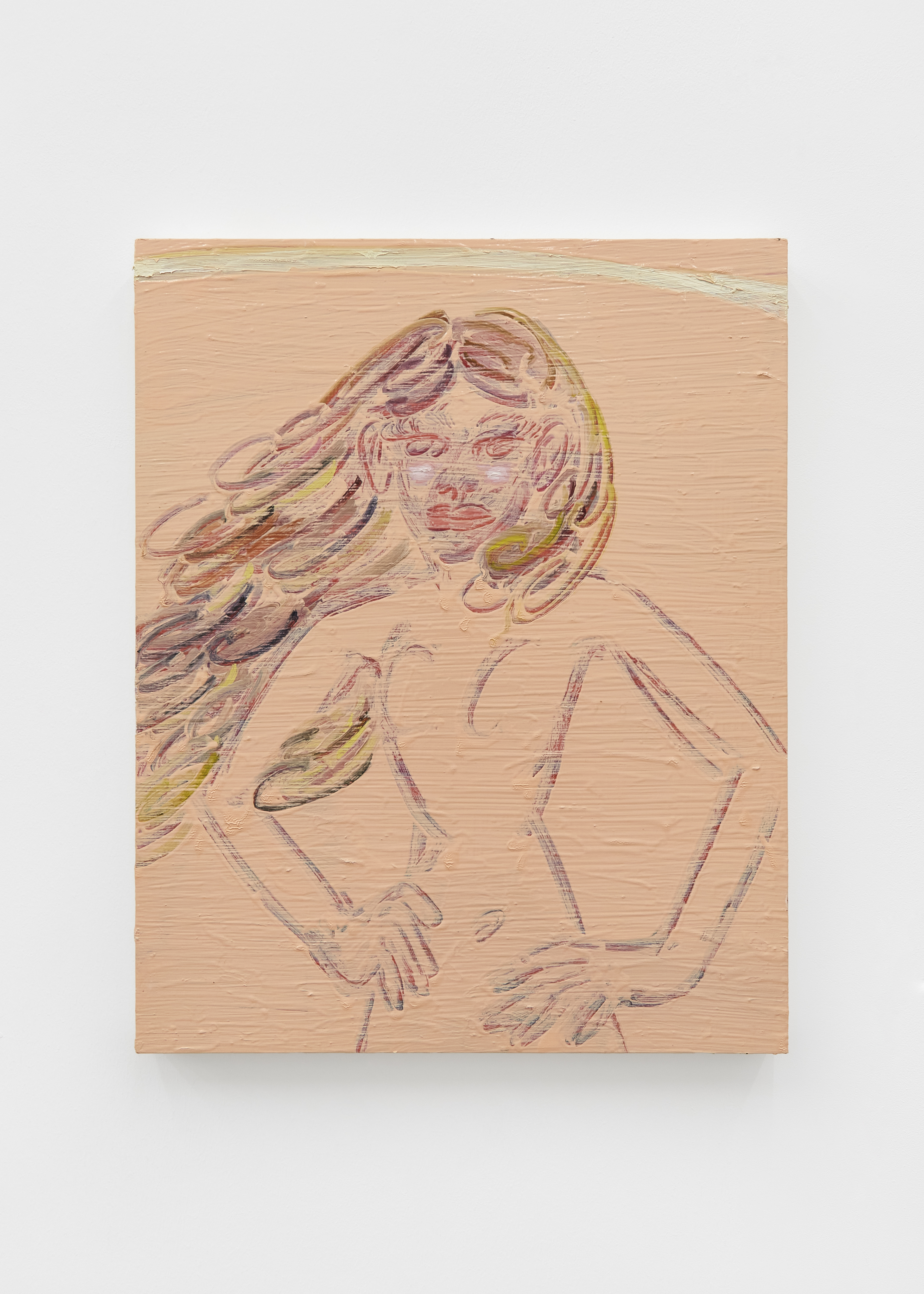

Raised on the work of de Kooning, Lee Krasner and Milton Avery, Schindler’s work exudes a sense of fluidity and ambiguity. Further citing influences ranging from old-style Disney characters and antique botanical wallpaper, the artist combines a charming illustrative style with gestural strokes and a unique scratching technique to depict figures reclining languidly leaning in and against their pastel backdrops, merging into one indecipherable composition.

Gal Schindler, Fire Fountain, In the Meantime, 2024. Courtesy of the artist.

At the heart of Schindler's practice lies an exploration of the human form. Her nudes serve as conduits for a multitude of emotions, embodying the fragility and mutability of the human, and particularly female, experience. Further drawing on influences from her childhood, the artist references intricately depicted anatomical drawings, her loose figures and strokes blurring the boundaries between flesh and canvas.

Undoubtedly spring-like in their palette, Schindler’s works are both optimistic and uplifting, with the artist referencing themes of renewal, regeneration and growth in her playful alternatives to traditional nudes depicted under a male gaze. There’s a sense of performativity, appealing to both a female and a younger gaze by creating fluid figures that defy categorization. Schindler’s paintings are sweet without being saccharine and sensual without being overtly sexual, instead, they occupy a liminal space between categories, appealing to anyone who may be a little ground down by moody palettes and sterile compositions. The transitory nature of Schindler’s composition speaks to the flux of the human form and an inability to contain and categorize the human form.

Gal Schindler, Live the Questions Now, Paint the Rain, 2024. Courtesy of the artist.

Gal Schindler, Crystal Clear, A Promise, 2024. Courtesy of the artist.

Wishing Well is a playful collection of fairy-tale figures that lean between sensual characters and traditional forms, with the transitory nature of the compositions creating a sense of impermanence that comes from the artist's unique technique of scratching into wet paint to create transitory forms. Schindler's works occupy a realm between landscape and figuration, where bodies float in a nebulous non-space. Beginning with instinctual colour planes, the artist overlays rapid structural lines, leaving behind traces of gesture and memory. The resulting figures blend seamlessly with their visual surroundings, their forms emerging from the depths of the canvas like reflections on still water, calling to mind the “Wishing Well’ in question. Life ripples on still water, Schindler’s figures remain distorted and alluring, half-emerging and half-hidden, they occupy somewhere between imagination and reality.

Wishing Well is on view at Ginny on Frederick, 99 Charterhouse St, Barbican, London EC1M 6HR, United Kingdom until May 24th, 2024.

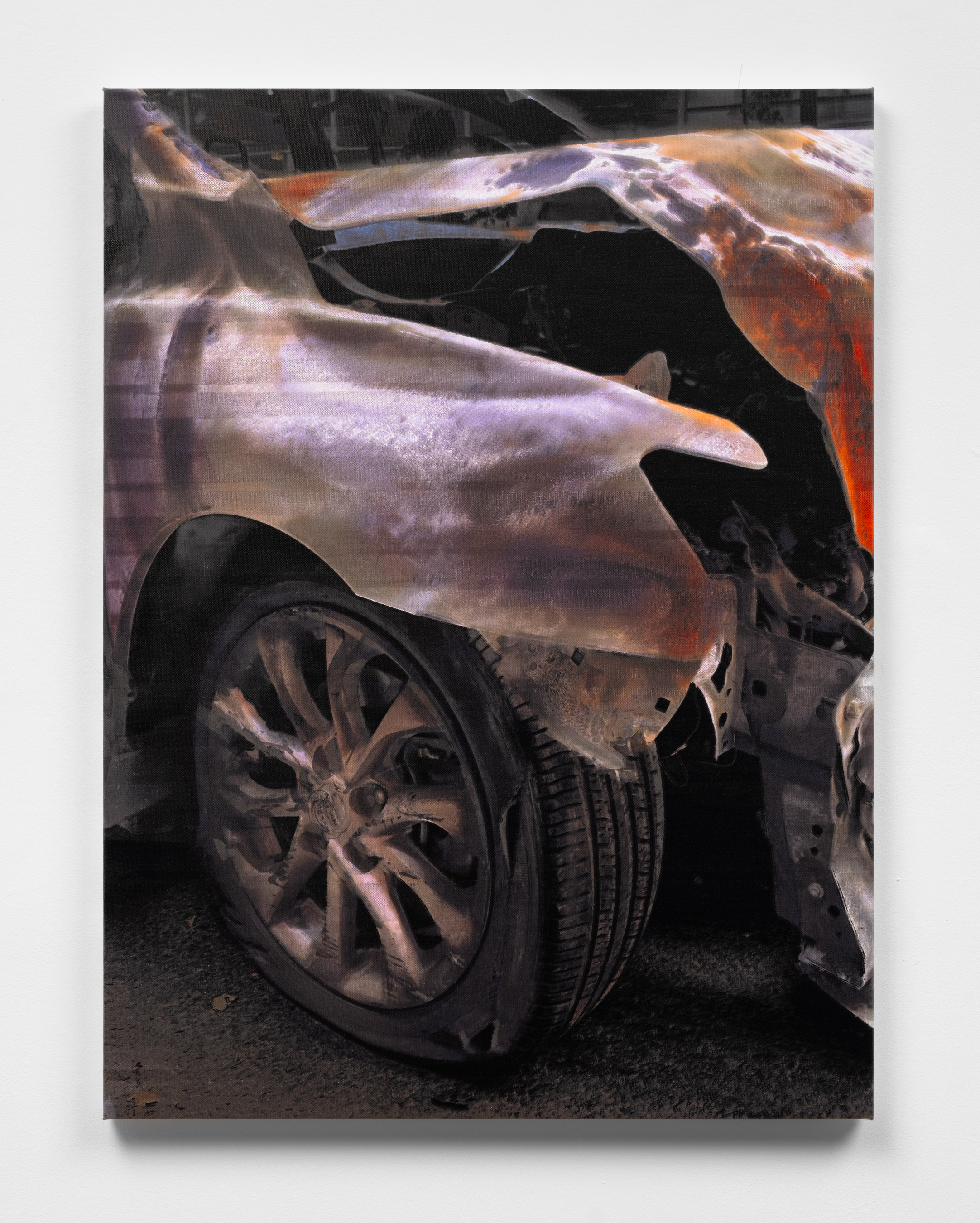

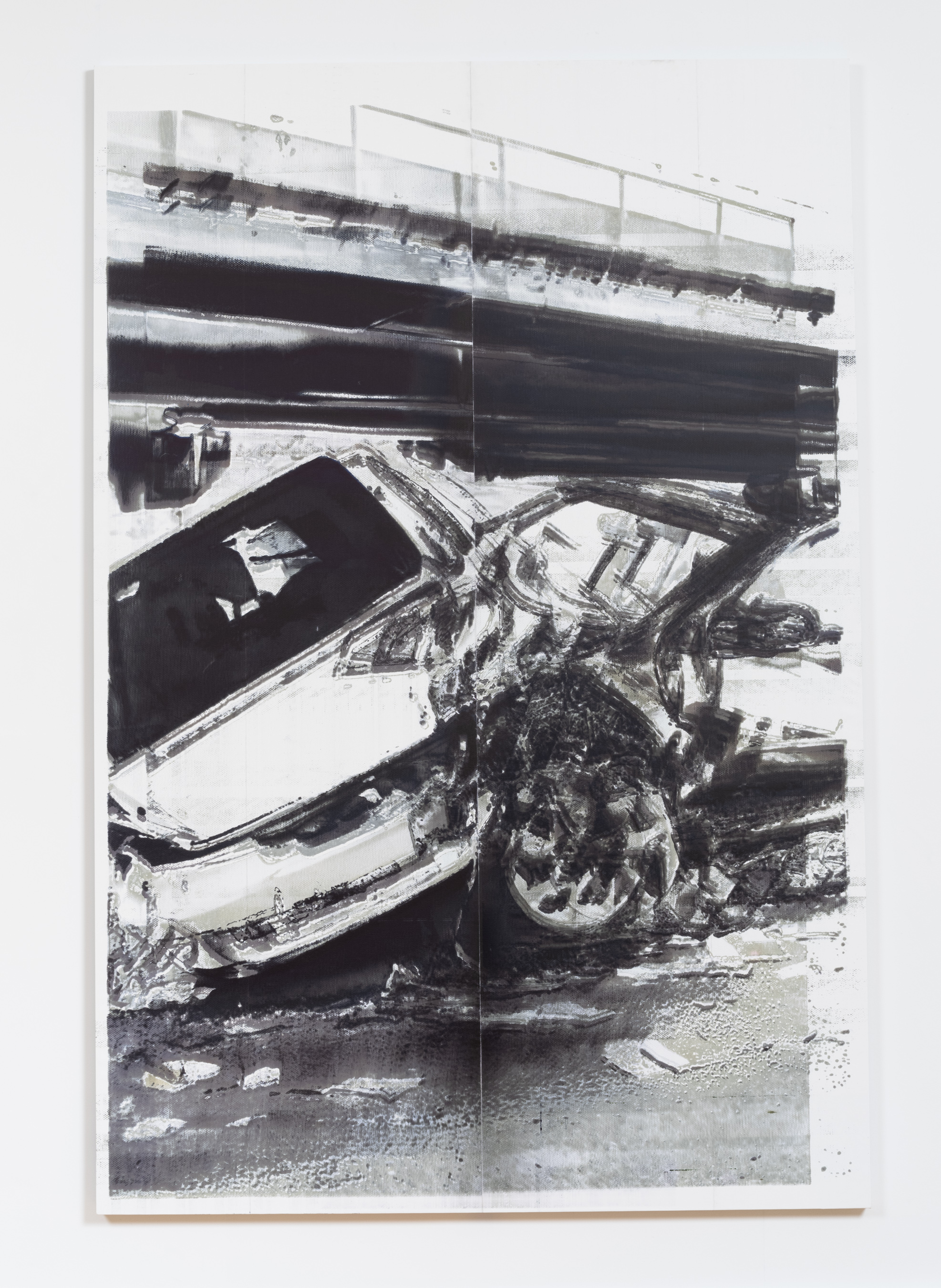

Thomas Blair, Crashed Car (Flat)

White Car Crash, 2024. Courtesy of the artist and Kapp Kapp.

Upon entering the show, the viewer meets Blair’s Crashed Car (Flat) (2024), a cropped snapshot of a wrecked vehicle, doused with splashes of violet and rust on its body. Upon closer examination, the image feels unstable or uncanny, not quite hand painted but also not entirely photographic. This effect of image hybridity epitomizes Blair's inkjet paintings — depicting generated images of car crashes (an overt Warholian homage to the Death & Disaster series), they interrogate how the feeling of a painterly moment can be manufactured in an iterative negotiation between human and machine.

In his towering White Car Crash (2024), layers of ink appear to vibrate and bleed into one another, an indication of Blair’s multistep process of producing images in AI, slicing them into layers, then repeatedly running each layer on canvas through a printer. The result is a reverse engineered painting — Blair’s approximation of a human touch via machine achieves, paradoxically, a potent expressiveness.

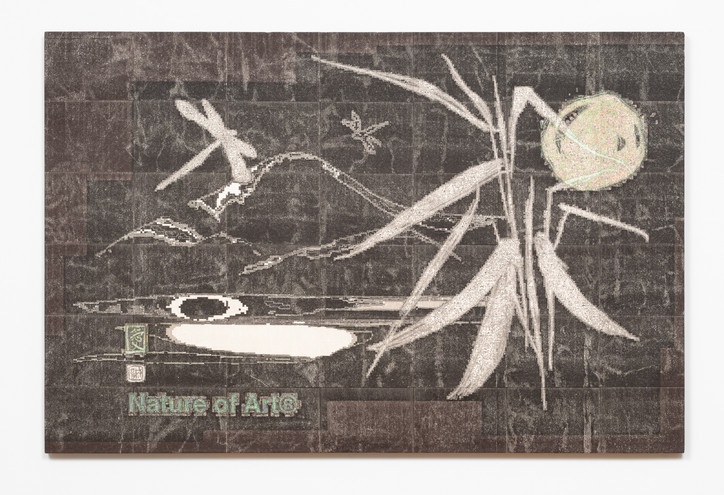

Kunning Huang, Untitled (nature of art), 2024. Courtesy of the artist and Kapp Kapp.

In Huang’s answer to the “problem,” his referential strategy summons the history of Chinese imagery and rice paper, attaining a lyrical balance between past and present. In the anterior of the gallery, his piece titled Untitled (nature of art) (2024) broadcasts the tongue in cheek thematic tagline “Nature of Art,” alongside imagery lifted from an early Qing Dynasty painting manuscript — a graceful pond scene, complete with grass stalks and dragonflies. But the objects and their surroundings seem tonally inverted and actively glitching, indicating Huang’s treatment of rounds of image processing in the preparation stages of his practice. Quilted in tiles, each panel of the work undergoes an intensive process: a specially rigged Canon printer impresses onto an acrylic sheet and thereafter, Huang rubs the printed ink directly onto rice paper, continuing a technique performed in ancient Chinese woodblock printing. The porous nature of the material causes the CMY ink colors to separate, culminating in a pleasurably pixelated texture. In this manner, Huang’s historically enriched approach demystifies present day conceptual concerns and technologies as existing within deeper lineages.

Waseem Nafisi, Bar Peasants (after Malevich), 2023

Second Impressions (after Malevich), 2023. Courtesy of the artist and Kapp Kapp.

Nafisi similarly leads with an art historical reference — the paintings of Kazimir Malevich — in his playful interventions into the thrust of post-modernity. In Bar Peasants (2023), a distorted copy of a brightly colored Malevich painting is bisected by a stretcher bar that literally juts out from either side of the canvas, while also appearing to nudge forward a horizontal sliver of the image — yet this tromp-l'œil unit remains physically flat on the canvas. Nafisi accomplishes this effect by constructing a to-scale miniature “stretcher bar” fixed onto a page from a Malevich monograph, then photocopied and printed onto the canvas. As Malevich serves as a stand-in for the crushing sensation of art history standing on one’s shoulders, Nafisi triumphantly pierces the purified image to assert his place in the “now.”

In Second Impressions (After Malevich) (2024), he employs a similar technique of flattened physicality, in this instance introducing a hand-painted wooden feature in the foreground. True to theme, the only occurrence of paint in this exhibition of paintings is merely an image of paint. This ironic demonstration reveals a self-conscious strategy by Nafisi: the painter’s hand itself becomes an image.

It may come as no surprise that as art school peers, Blair and Huang both trained as photographers, while Nafisi studied more traditional painting — all three departed their mediums and converged in the center at technologically-driven painting practices. The culmination of these young artists’ experiments suggests that painting can trudge through the societal jungle of images and increasingly intelligent technologies of today by borrowing from the toolkit of the past — a promise that digital acceleration can, in fact, enhance the joie de vivre of making and experiencing art.

Canon is on view at Kapp Kapp, 86 Walker St 4th Floor, New York, NY 10013 until May 11, 2024