The Artist and the Cigar Box: Civil Pleasures

Check out photos from the opening night below and put your bids in here. The Artist and the Cigar Box online auction.

The Artist and the Cigar Box is on view online through June 30th.

Stay informed on our latest news!

Check out photos from the opening night below and put your bids in here. The Artist and the Cigar Box online auction.

The Artist and the Cigar Box is on view online through June 30th.

The Jamaican-born, New-York based artist has long been fascinated by objects. His best-known work, Amazing Grace (1993), featured over three-hundred baby strollers that the artist scavenged from the streets of Manhattan and then installed in the walkway of an abandoned Harlem fire-station. A statement on the AIDS crisis and drug epidemic ongoing in New York at the time (the strollers were often used by the city’s homeless population), the piece foregrounded Ward’s focus on utilizing found materials to tell stories that their human counterparts could not. Over the next three decades, the artist continued to work with such materials — shopping carts, bottles, doors, television sets, cash registers, and shoelaces included — and translate their silent language into a more readily accessible dialogue. The resulting practice is one filled with intimate links to the world around it: it sings of previously undiscovered connections, alerting us to the unspoken ties between us and our possessions.

Nari Ward: Ground Break (28 March- 28 July 2024), a retrospective at the Pirelli HangarBicocca in Milan, offers an up-close look at this practice through a number of Ward’s sculptural installations and video works. Curated by Roberta Tenconi with Lucia Aspesi, the show begins with Hunger Cradle (1996-2024), one of the first large scale installations that the artist created in the 90's as part of the “3 Legged Race” exhibition in New York. A complex network of interlaced threads, Hunger Cradle unveils found objects — car parts, fire horses, a piano — that Ward collected from around the original show’s building and then embedded in the piece’s structure. Here, the work has been further enriched by new materials sourced from around the Pirelli HangarBicocca, including bricks used in the exhibition’s titular piece, Ground Break (2024), a sprawling floor installation made of over 4,000 concrete bricks and topped with decorative spiral motifs that resemble celestial bodies.

Although not the exhibition’s center piece, it is Hunger Cradle (1996) and its implied sense of support that best serve as a metaphor for what Ward, or so the viewer might be led to believe, is trying to express. From the dead fish whose carefully skinned flesh line the floor of Super Stud (1994/2024), a small house propped up on metal studs in the exhibition’s main room, to the tangle of stray shoelaces that make up Tumblehood (2015), a spherical sculpture that mimics a tumbleweed, what emerges above all is the artist’s desire for preservation amidst the never-ending flux of life. There is a dash of the mad collector here, or perhaps something of the old Proustian goal: to regain what is lost. Still, Ward goes beyond merely accruing disparate materials or using objects to recount past experience; instead, he takes things in, provides shelter, then suffuses them with his particular magic, which is also his art.

The show, on view at the Pirelli HangarBicocca’s cavernous space north of Milan’s city center until the end of July, affords us a previously undisclosed peek into the minds of one of America’s most compelling contemporary artists. It —and its many oddities and beauties— is not to be missed.

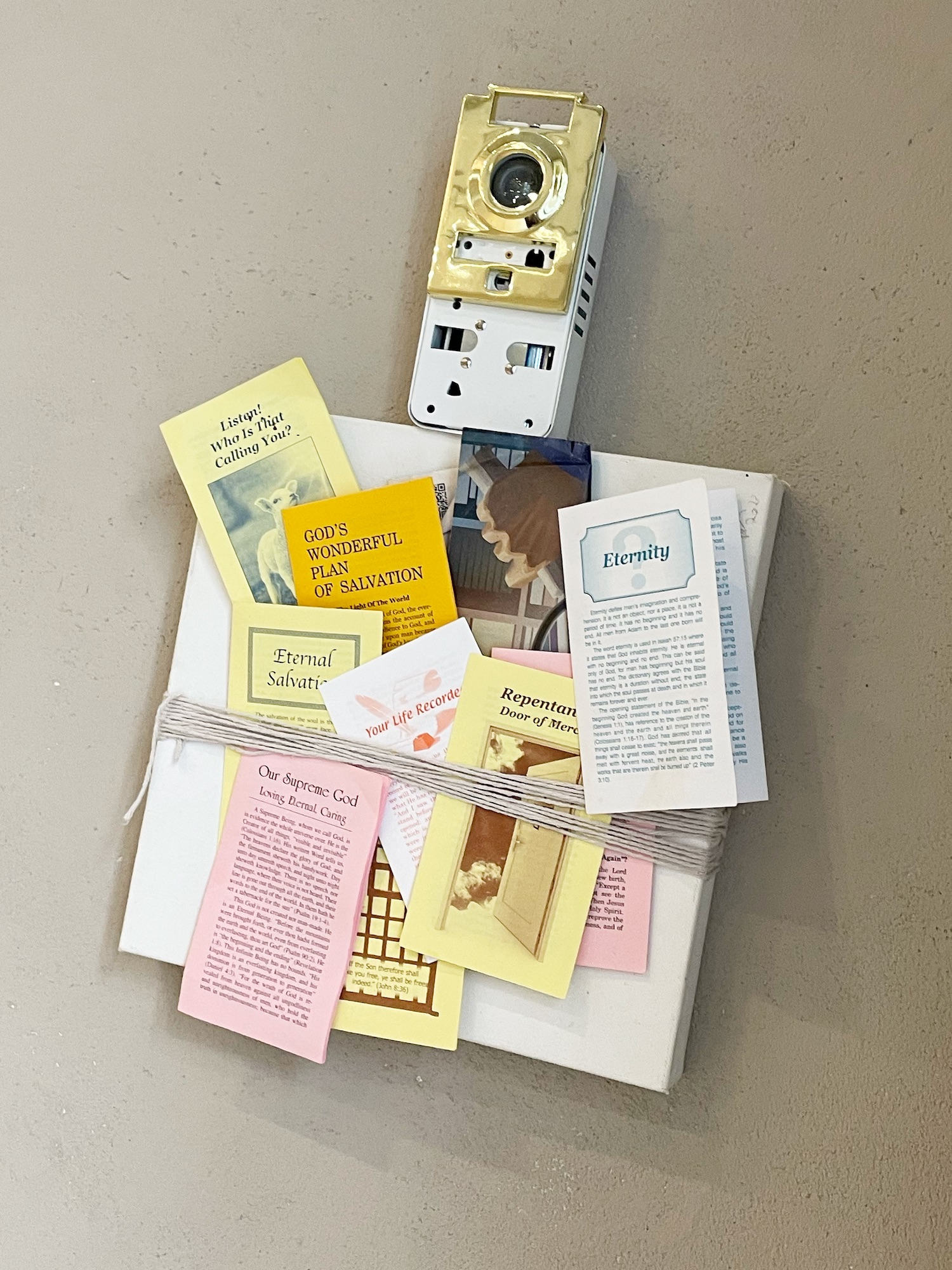

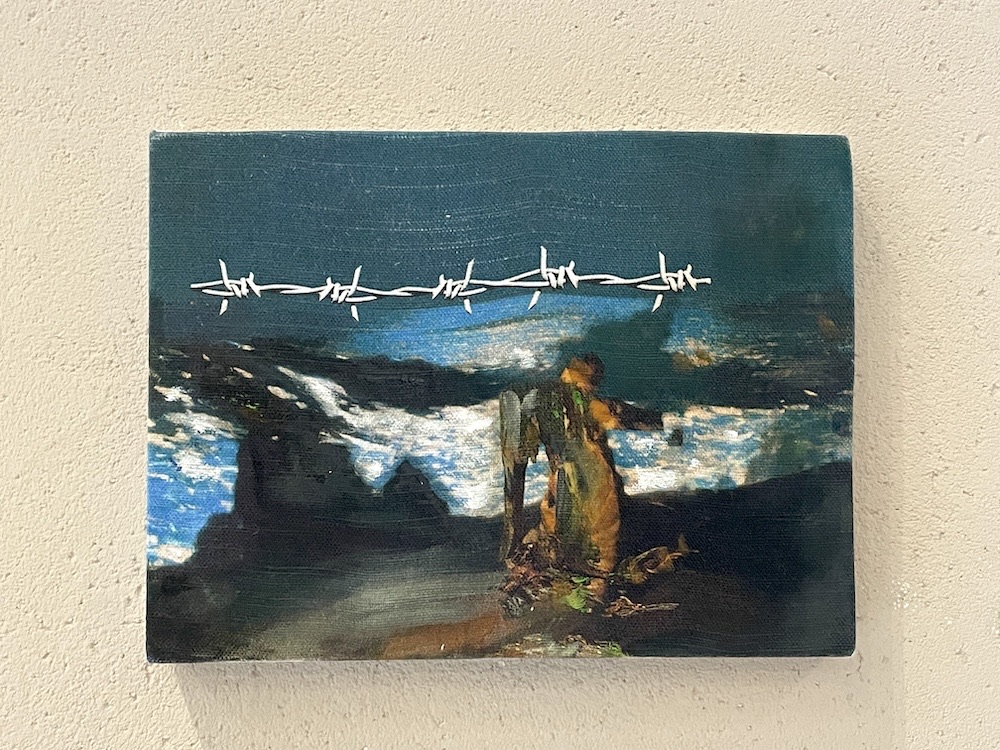

“Innocently, I intended to create a white box to address the context in which we give art value, both monetarily and culturally. But as the show developed and through spending time with the artists and hearing their questions for me- It became clear that a part of me wanted to prove I could do something institutional. I think I wanted to not only assert the work, the artists, and myself into the canon but also justify our existence in the art world, which has left me with a lot to think about. That level of provocation was intended. I didn't realize how I am also a part of the audience I was hoping to interrogate," Greer-Mathurin expresses.

Optogenetics, in the metaphorical sense, is about manipulating light to illuminate the depths of the human experience. "I think seeking that light out will always control me, seeking it and finding ways to share it. To me, curation has always been a conceptual act- not providing interpretations but providing a space to call things to attention. Curation comes from the Latin "to take care of," but I don't think it means only art; it means to care of the way we see life," Greer-Mathurin explains.

As you step into the space, the once-pristine white floor is marred by tracks of dirt and footprints despite being painted just two weeks prior. Ceramic cockroaches, Jester Bulnes's LAS CUCARACHITAS sculptures, embellish the walls and corners of the gallery, symbolizing artists' infiltration into the art world. A cohesive curation of artwork fills the space, where each piece can breathe and draw viewers into their captivating orbit.

For many of the artists, this exhibition marks their first foray into the gallery setting, offering visitors the opportunity to experience the exhibition through May 17 by appointment. Curator Blessing Greer-Mathurin makes her solo curation debut, unveiling her keen artistic sensibilities and genuine admiration for each participating artist.

“They’re all effervescent. I have admiration for the art of how they live. How they ask questions, how they ask for help, how they treat their friends. Everyone is sensitive, sweet, and wild. They all approach art-making with such vigor, vitality, and attentiveness and somehow find a way to remain open to the world. I know they’re special. I think they will be here for a long time; I want them to be here for a long time, and I know they will. I’m a better person for the time I’ve spent with them and their work,” the young curator explains.

On view through May 17, ‘Optogenetics: Controlled by Light’ presents an immersive exploration of the young LA-based artists' minds, delving into questions of identity, cultural investigation, and introspective musings.

Before the show's opening, I asked each artist the same two questions regarding their practice, medium(s), and influences. Explore the interviews below.

Mushkinaz, 2024. Graphite on paper, found objects. We Are Eternal Like Our Mountains, 2024. Ceramic. Orthodox Cross 1, 2024. Ceramic. Caucasian Figure, 2023. Cyanotype on fabric. Shepherdess, 2024. Naturally dyed textile, ceramic, found object, synthetic hair. Mother's Boots, 2023. Ceramic.

Could you share the medium(s) you typically work with and why? What materials do you find most inspiring, and how does it inform your creative process?

I am a drawing and figure drawing teacher and my background is in 2D figurative work, which is what you will see in the show. For the past few years, I have taken from numerous mediums, including drawing, to create installation-based pieces as well. I fell in love with quilts in particular not only because their function in history meshes with my conceptual framework but also because their hybrid form allows for the convergence of many materials and techniques: through printmaking, airbrush, photo transfer, ceramic pieces and found object assemblage, I assemble quilts that materialize trans-generational narratives. The figure, often an imagined female ancestor, is still present in my pieces, even if it is only implied by the objects surrounding it. My work honors stories of displaced Armenian mothers and daughters, whom I adorn with objects that may have followed them to their graves. In the face of displacement still today, the quilts act as handmade textile documents that can be passed down through generations.

How do your external surroundings, archives, and consumed media influence your art practice?

I moved to the States from Yerevan at a young age and grew up in Glendale– being Armenian was always a big part of my identity. I was raised with Armenian folk music, poetry, food, and soviet television alongside American culture, characterized by a fascination with 70s rock and coming-of-age movies set in the Midwest. And then there are the weird dolls, miniatures, old objects, sunsets, things I incorporate in my art and always liked growing up that can’t be easily attributed to either. Maybe the obsession with nostalgic things and imagery has something to do with missing out on a past in both cultures as a part of a newer, hybrid culture– maybe not. All to say that sometimes a cultural element is more legible in my work than other times, and I love that the hybridity of the multi-medium quilt allows the expression of a unique, composite, and complicated experience.

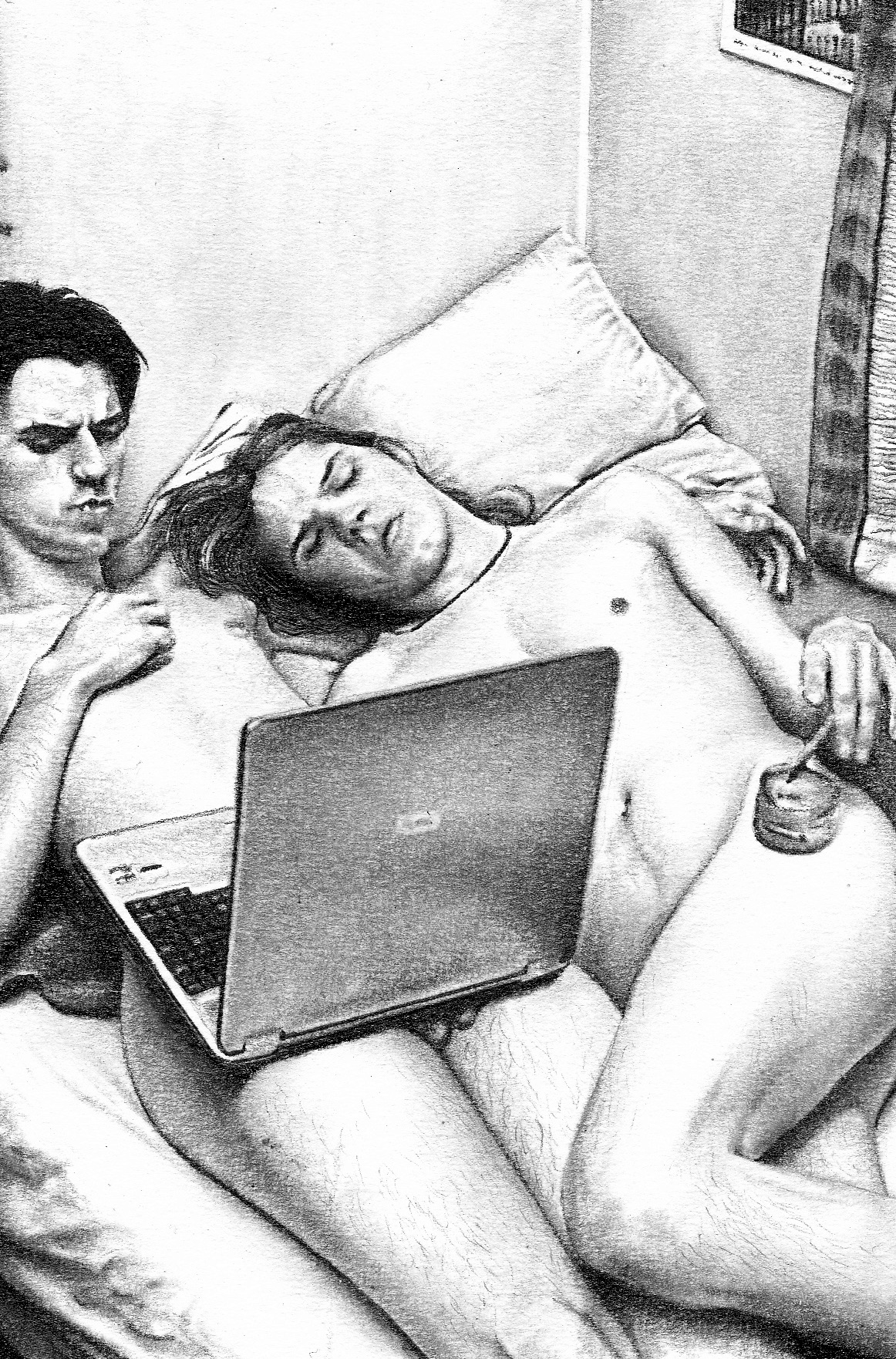

Could you share the medium(s) you typically work with and why? What materials do you find

most inspiring, and how does it inform your creative process?

Photography is probably the medium I have been working in for the longest. I strictly shoot film because of its material quality. In a wa, it feels much more tangible than digital photography; it's physical and tactile and allows for me to slow down my process because of the time it actually takes to see the photos. I usually go to a lab for processing, but then I either scan or print the photos myself, which allows me to spend even more time with the work.

I also often work in ceramics, painting, sculpture, and performance. I think certain ideas lend themselves to specific materials. A lot of my work is rooted in intuition, abstraction, and feeling—and for that reason, I try not to close myself off from any medium, but at the same time, I am very intentional when I do choose to work with any given medium and choose materials that feel reflective of that. Right now, I find myself really returning to photography and trying to find ways to incorporate other mediums within my photo practice, whether that be through directly what I am photographing or rather how I go about creating the photos to exist in the world, such as thinking about different printing surfaces and I am starting to make my own frames.

I think I feel most inspired by materials with a history—a personal history. I am really interested in found objects and have started to dive into my own archive of materials and think about the ways in which I can start to incorporate these things that I have kept with me for so long or that I see continuously showing up in my life, such as wig caps and lace, within my art practice. Materials exist for me as a code, a secret language.

How do your external surroundings, archives, and consumed media influence your art practice?

I think most of my work, if not all, is informed in some way by my external surroundings. I think it's quite the special hybrid of curated media I allow myself to spend time with, infused with me, that blends into each other and becomes my work. As someone who grew up in LA, this city has most definitely influenced my practice. There is so much culture here, textures, and grittiness that I find myself constantly returning to. I try to reference my own archive more than anything. For me it’s important to take in these outside sources and to feel inspired, but I always have to embed myself into the work in some way.

Tsunami, 2024. Watercolor on Watercolor Paper

Could you share the medium(s) you typically work with and why? What materials do you find most inspiring, and how does it inform your creative process?

I'm a composer, so typically I work with sound, and physical material has only factored into my practice insofar as it serves this aim. For my recent work, I've been interested in painting that skews towards ink, trying to find the sweet spot between writing and drawing. I'm very inspired by Islamic Calligraphy and Hieroglyphics as of late, so finding a material that can evoke both but still hold its own has led me to gouache. I like gouache too because I think it's a crowd-pleaser; I haven't met anyone so far who has said they don't like it. To me, using gouache is like throwing a bone to the audience like, "Hey! I appreciate you taking the time to check out my work!" hahaha

How do your external surroundings, archives, and consumed media influence your art practice?

I've been deep in research about tuning systems throughout North Africa and the Sahara, so I've come to virtually (in the virtual sense) surround myself with recordings from wherever I can find them. I don't have a cassette player, but I wish I did, and with that, some old cassettes from the regions I'm looking at that I end up listening to after they've been digitized and uploaded to youtube. Ok, this is interesting; being based in Detroit has influenced my sense of structure as a musician and, thereby, my sense of composition as a visual artist. Detroit music is so structured, much more than what I became used to coming up in Los Angeles. Whether it's jazz standards, techno, or R&B, the harmonic and rhythmic structures are built upon, built up, like a gearbox or something. That has definitely done a lot for me, so shout out to Detroit!

Bacadle; Hargeisa, Somaliland, 2023. Framed C-print under museum glass.

Could you share the medium(s) you typically work with and why? What materials do you find most inspiring, and how does it inform your creative process?

I work in photography and video direction. Although I think there’s a great deal of gear that could be useful, I definitely have to fight the urge of placing too much weight on the tools I use because I think it could easily be a distraction. For instance, I have a single camera, and I’ve employed a similar lighting rig for the past five years. That being said, specific materials have undoubtedly influenced my workflow.

I started taking photos around 2016, initially drawn to the mechanics of 35mm photography. It really seemed like an insane and archaic process of making images that I found interesting, so I purchased my first camera, which was an Olympus OM-10. For the next few years I shot photos in a very exploratory manner, following whatever compulsion that drew me. Later, I decided to transition to using the Mamiya RZ67 for specific reasons that align with my approach to photography. The substantial nature of the RZ67, combined with its limited frame count of 10 images per roll, intensifies my creative process. It’s really heavy and slow, which pushes me to be even more deliberate and thoughtful with each shot.

I like to think this ultimately is all in service of the story that I’m trying to tell. While I appreciate the tactile experience of film photography and the tools I use, I care about creating photos that resonate with me personally and convey certain emotional narratives that I experience.

How do your external surroundings, archives, and consumed media influence your art practice?

There are a few things in my life that are as significant as my relationship with work that I deeply resonate with. I feel infinitely fortunate to interact with art that speaks to my experiences and emotions in a way that not only profoundly connects me with the respective artist but also helps me understand myself to a deeper level.

I find inspiration in the works of select individuals who are able to convey a sense of empathy and insight, creating stories that speak to the human experience and our longing for connection. I constantly feel like I’m on this journey to discover more artists/work that operate within this certain frequency.

I was reading this book on Eggleston and I think this quote gets at a lot of the themes I’m interested in. “In many instances, the subject was unaware of being photographed, [making] these images have a distinct, voyeuristic quality reminiscent of the paintings of the American artist Edward Hopper. Like Hopper, in this early period, Eggleston gave a sense of the individual being enveloped by urbanization and development but alien to it. People are shown not in the artist's studio but in the context of their surroundings. They appear in semi-public places like diners, petrol stations, phone booths, and markets; they are surprised, caught at awkward moments, or lost in thought.” Ultimately, I am drawn to works, whether in music, photography, or film, that delve into themes that I feel deeply impacted by.

Cerro Lonquén, 2024. Cotton, wool, terra cotta, copper, non-human collaborators (chia seeds, agents of decay).

Could you share the medium(s) you typically work with and why? What materials do you find most inspiring, and how does it inform your creative process?

I am a textile artist, and my main medium is weaving. I also work with embroidery, quilting, sewing, felting, ceramics, and installation.

I am interested in the potential of theorizing with wool. As a diasporic Chilean, I feel a strong resonance with materials and technologies that are part of my ancestry, and I sense that these materials can activate alternative and reparative politics and histories. As such, I work primarily with sheep’s wool — a traditional South American weaving fiber — and I work on Chilean-style frame looms. I also work with other natural materials such as cotton, ollá/terra cotta, and copper. All of these materials index Andean lifeways, and I consider them agentic collaborators in my projects.

How do your external surroundings, archives, and consumed media influence your art practice?

Archives are a very special and emotion-filled place for me. My first introduction to cultural work was in archives, and long before I began honing my art practice, I was working in archival settings. One of the most transformative experiences of my life was working as an archivist intern at the Museo de la Memoria y los Derechos Humanos in Santiago de Chile. The Museo is Chile’s largest and most advanced museum, and it focuses on memorializing the victims of human rights abuses during the Pinochet dictatorship. My role was focused on investigating and archiving a collection of documents from the Casa de Chile en México, a political and cultural organization of exiled Chileans living in México during the dictatorship.

Much of the role focused on preserving documents by producing cleanliness and sanitized interfaces that could be easily stored in acid-free storage containers. While I understand and respect the importance of keeping a well-maintained archive, I felt so much resonance with the documents that were already damaged. For example, many documents I preserved were newspaper clippings that had been pasted onto sheets of paper by employees of the Casa de Chile en México. These documents were hard to preserve because they had already been physically transformed and manipulated, often without “proper” archival materials.

However, these papers were indexing the history of political violence and the Chilean exile. Even if all the text had faded away, I could still feel the labor of the exiled archivist, cutting and pasting newspaper articles, when I interacted with the documents. Their materiality was able to communicate with me through emotional intensities without and beyond the limits of language.

This experience opened the door for me to think more broadly about the agencies and potentials of materials as collaborators in the challenge and opportunity of living a post-dictatorship life. It is with this mindset that I turned to weaving. In a context where many hegemonic international actors try to quickly and unjustly resolve twentieth-century political violence, I see weaving as a way of visualizing the textures of an afterlife. The archive is a space that is often sanitized, filled with silences, and infected by fevers, but I also feel that by respectfully reframing the matter of archives as survivors, I have been able to materialize alternative histories that center healing from historical injustice.

Tourist, 2021. Parking meter, braiding hair, fan, burlap, glue.

[...]

Impression of an Artist’s Ladder (Vrymoed), 2023. Pigmented silicone.

Could you share the medium(s) you typically work with and why? What materials do you find most inspiring, and how does it inform your creative process?

I’ve always worked in a variety of mediums and materials, but most recently, I have been working with glitter on cardboard. I value the medium for its simplicity and accessibility—it’s an “arts and crafts” project that many children are shown when they are still in grade school. (I was one of these children.) It’s of a world of cultural practices that appear even lower than “craft” on the supposed Arts>Craft hierarchy. I think it’s because “arts and crafts” are associated with women and children making works outside of long-term, established traditions of “craft” like weaving, ceramics, woodworking, and brewing. Playing against normative notions of “value” is a bit of a cliché, having been a mainstay of contemporary art for over a century, but I think it’s still an important approach to making. It’s an important position to take as an artist, to align oneself and one’s work with that which hegemonies undervalue or actively devalue, with what they don’t take seriously.

The works in this show are from a slightly older series called “Impressions,” a body of work that revolves around ladders used in artists’ studios. They are slapstick odes to these devices that are essential to making art in one way or another (even if they’re only ever really used to help folks screw in lightbulbs) but are uniquely marginal in their utility and the kinds of attention paid to them as objects. They’re the tools most responsible for elevating artists, and so I work to elevate them.

How do your external surroundings, archives, and consumed media influence your art practice?

In ways that are as obvious as they are incomprehensible.

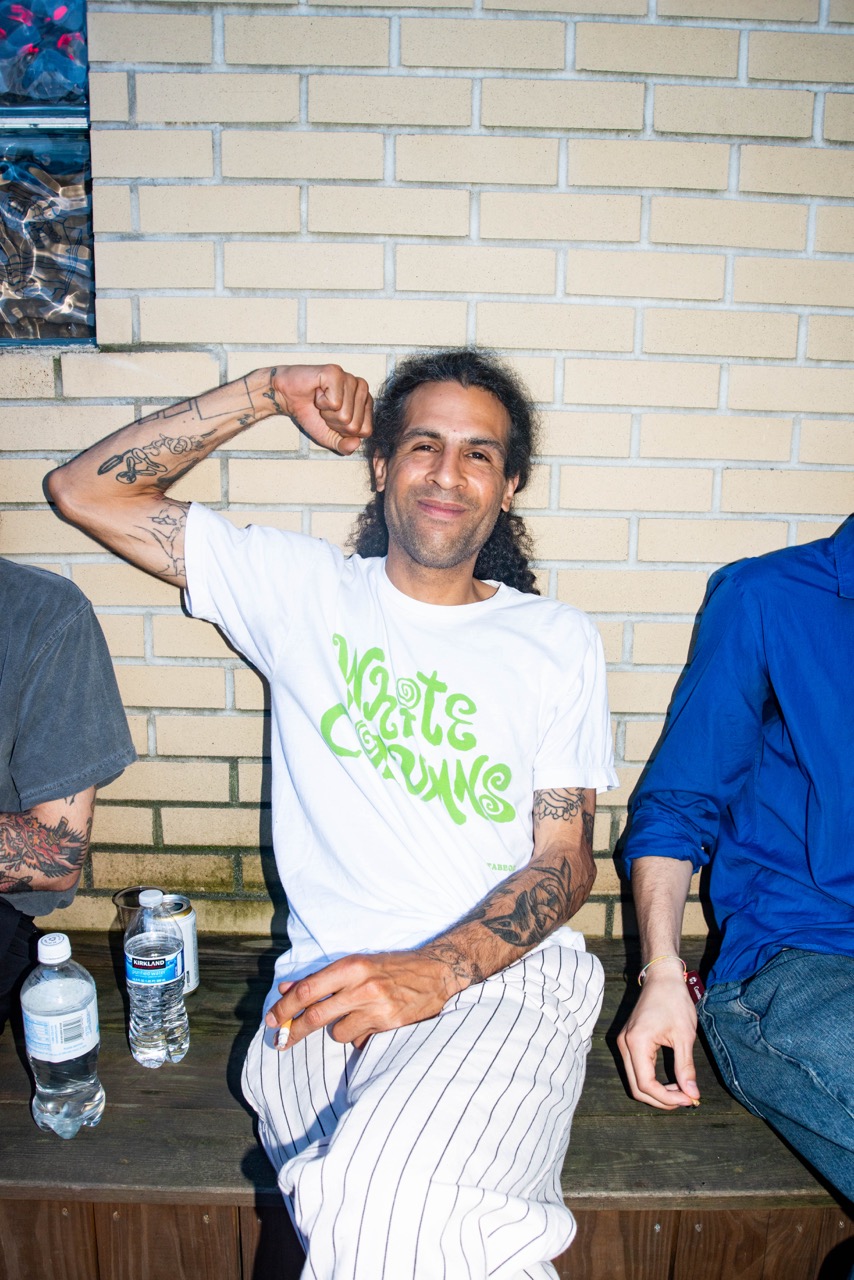

Gordo, 2024. Glass, stoneware and plywood.

Could you share the medium(s) you typically work with and why? What materials do you find most inspiring, and how does it inform your creative process?

The mediums I typically work in include but are not limited to poetry, ceramics, wood, metal, earth, wax, found objects, sculpture, performance (specifically free jazz/improvisational cello and ensemble outfits), site-specific installation, and artistic collaboration. I find them all to be of equal value and tend to lean into each of them as ideas develop and evolve naturally with my practice. As corny as it sounds, I follow my intuition, faith, and ancestors through the work, and as I am led, I allow myself to be porous – thus, the memories and thoughts that are my own and those that I am blessed with by the ones that came before me, are all shaped into a material presence which I believe honors them, myself, and the ones to come.

How do your external surroundings, archives, and consumed media influence your art practice?

Some other influences are my family and friends, faggotry, Blackness and Brownness, the Dominican Republic and Haiti, the Caribbean, Latinx culture, music, transness, dreams, love in all its forms, nakedness, play and silliness, water, sexiness, sex, gay sex, anger, breathwork, aromatherapy, regular therapy, some of my exes, the natural world, the unnatural world, the supernatural, the death of empires, Taino and Arawak rituals, indigenous cultures, native medicines, weed and blunts, food, modern luxury, ancient luxury, Southern Baptist churches, gay cruising, animals being sweet to each other, stuffed animals, celibacy, boys I have a one-sided crush on, tobacco, and “truth.”

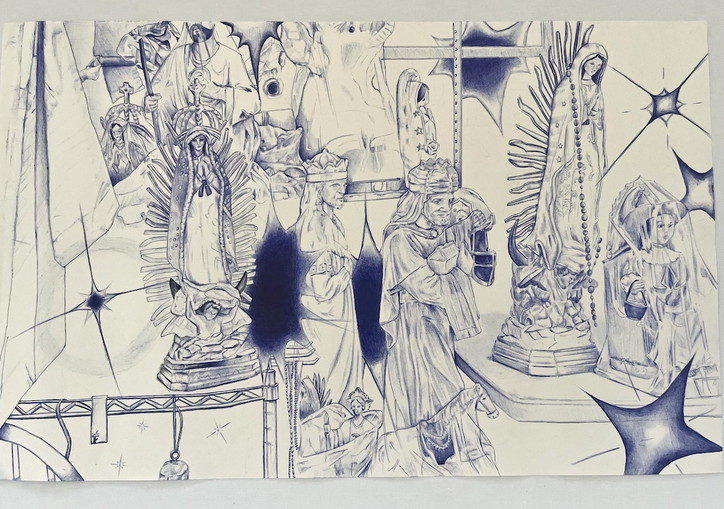

Studies for Operation Jericho: Alameda St. (Alameda Swap Meet), 2024. Blue Ballpoint ink illustration.

Could you share the medium(s) you typically work with and why? What materials do you find most inspiring, and how does it inform your creative process?

In my studio practice, blue ballpoint pen has become my primary medium, which I then combine with other mediums like wood burning and acrylic paint. I was first introduced to the ink-based medium as a child growing up in South Central with system-impacted relatives. I have great admiration and respect for all incarcerated and justice system-impacted artists, and I hope my work honors them and sheds light on their work as well. This connection is what I find most inspiring about working with the blue-inked pens. There's an inherent nostalgia embedded into the medium and its history, but I also like tapping into the hope that is there as well. The concentration it takes to make finely detailed work with blue ballpoint pen exemplifies the community-building skills and dedication all artists working with the medium (including those within the unjust, industrial justice system) can translate to and use for building more just worlds.

I’m also a muralist working with acrylic paints based in Los Angeles. Please visit my website for a portfolio of my mural works, and feel free to reach out with any projects.

How do your external surroundings, archives, and consumed media influence your art practice?

A cornerstone of my art practice is the familial photo archive that I’ve been stewarding over the years. This has been the crux of my art practice and an important practice for me as part of the Nahua diaspora. Not many written records of my familial history exist. It’s up to me to tell our story how it should be told, and recover ancestral knowledge and tools.

Another truly integral part of my art practice is observing my external surroundings– the visuals of the ecologies and histories of South Central, Los Angeles, and Mexico. I’ll be called to an external visual in my surroundings and then, in diving into its history, learn each and every time that there are connections to be made between the history of the visual, the history of the land, and the history of my community. That drives my studio practice and, of course, influences my mural practice.

Quilt I, 2024. Cotton, natural dye, wax thread, delta airlines blanket.

Could you share the medium(s) you typically work with and why? What materials do you find most inspiring, and how does it inform your creative process?

I typically only work with textiles, but I'm trying to branch out with other mediums like photography. I've been working with textiles for about four years so far. Starting off with latch-hooking, weaving yarn and wool into canvas and recently exploring how to teach myself how to quilt. I’m not sure why I gravitated towards textile art, but why I continued to pursue it because It brought friendship and a way for me to leave Missouri. I wouldn’t have been able to leave my hometown (Saint Louis) without pursuing this medium and challenging myself to get better with the craft.

Photography inspires me the most because of references. My early work was all references to different people or movie scenes and then turned into only wanting to reference my own photography. Only images I've taken and reference poses from different magazines, books, or random Tumblr posts for my subject to copy or alter. Photography constantly inspires and informs me because I’m constantly looking at images all day and screenshotting nonstop.

How do your external surroundings, archives, and consumed media influence your art practice?

Recently, going on walks around Highland Park (where I live) has influenced my quilting. Seeing random structures or random furniture outside, looking at the colors of the two. Or even tarps on the ground have made me want to display my quilts in a different format so I can eventually transition from hanging them on a wall. Looking at a medium that doesn’t have anything to do with the medium I’m working on influences me more. My roommate Deshion is a big influence on me; his painting experiments with color, and he’s making sculptures that motivate me every day when I wake up since sharing a workspace.

Check out scenes from the opening below and make sure to visit Optogenetics, Controlled by Light at Room 3557, running until May 17.

Paul Hameline — It involved several coffees, a bunch of beers, nighttime, daytime. Several back and forth, it was all quite similar to a tennis match really. I would send Paige one image, she’d reply to me with another one. Same with texts, Paige would send me a text excerpt and I’d reply by sending her another one. Eventually things started taking shape in an organic way, and we would simply orient the narrative in a direction rather than another.

I’m sure you were uber excited about all of the artists included, but was there one in particular you were looking forward to presenting to this local audience (maybe new to them)?

Paige Silveria — That’s obviously really hard to answer. Though I want to say that I found Gogo Graham’s self portraits really special. I met her years ago when I interviewed her about her fashion show in New York. As a trans Latinx fashion designer and artist, her runways were these incredible, conceptual presentations. You really felt like you were immersed in an art performance. Recently, I saw that she’s been taking a bit of a step away from fashion and focusing on her art, especially paintings. So I reached out to see if she might want to show one with us in Paris. I love these two portraits she allowed us to include so much. One is her when she was this adorable little kid with big ears and the second is later, as this like glamorous icon.

And this wasn’t your first show in the space, right Paige? How would you compare the two?

PS — The first thing I did was a curatorial collaboration with Arcane Press magazine for the release of their first issue. The aesthetic was a bit darker and moodier and really focused on the artists included. This show with Paul was a bit more personal and organic. We spent months chatting between the US and Europe and with coffee on walks when I’d finally returned to Paris. We would send artists and work we loved and discuss the complexities of why they made sense for this little world we were creating. Then trying to articulate what the world was turning into with literature … It was a really special and fun project to do between friends. And we really took our time.

I loved coming by the night before the opening when unfinished and seeing it the next day, how late did you stay?

PH — Not so late after you left, must have been 10-10:30. Once we were done, we went for beers, some cigs and giggles.

PS — I love the install. It’s so exciting to see everything together finally after staring at images on your computer or phone for months. Things are tangible and you can start to really craft the physical world that previously was only in our heads.

What was your favorite part of curating together?

PH — The thought process, the research, the exchanges etc. Paige showed me artists and authors I didn’t know, I’d reciprocate by making her discover some she wasn’t familiar with. Sharing is caring. We obviously are two different people with our own ways of seeing and experiencing, so merging the two in order to give birth to that show was a great experience.

PS — It’s been a while since I was able to put a show together with someone from the inception. I really loved to be inspired by his way of thinking and being introduced to new communities of artists. It was also pretty exciting when we realized that our separate ideas were super similar and the vision was happening in tandem. Things worked so smoothly; we somehow emerged with the same aesthetic in mind.

What led you to the title ‘Preservation’? What are you preserving?

PS — The title was pulled from the excerpt (in the press release for the show) from Robert Pirsig’s book Lila: An Inquiry into Morals. With the title, we’re analyzing civilization, societal structure, moral grounding — preservation of what exactly? Of whom? At what cost? And why? It’s less of a statement, or a desire to preserve anything, and more of an inquiry to begin the conversation.

In an interview I read recently, Hans Ulrich Obrist said that “good curation is working with someone who can do something you can't.” He also called curation a kind of junction-making, creating these avenues where people and ideas meet and interact. Do you agree?

PH — That goes without saying. The basis of any relationship is to give and take. You have something to offer, and the person sitting in front of you has something to give you. We grow through our relationships and encounters, from a lover to a stranger asking you for a lighter.

PS — My favorite take away from Marx was when he said that human relationships are the point of our existence. I think that’s any conversation and exchange, even reading the book of someone who’s past … With these shows it can be so exciting bringing people together. A while back I did a Good Taste show in LA and was showing work by two really iconic artists, Erik Foss and Erik Brunetti. Although they’d been aware of each other for over a decade, they only finally met when we began installing this show. It was really cool to listen to them discuss things from over the years that one another had done that’d made an impression on them. Even just small connections like this are a part of why I love to curate — not just about making sales!

What conversations are you hoping to nudge into existence with this show and those to come?

PH — The way I perceived it, it’s about how civilization reached a point of no turning back, it’s about creating some kind of world within oneself, against the turmoil present in today’s world. We tried to create a safe haven, some kind of fort. A dystopia slowly leading back into utopia. A bit like Peter Pan and his Neverland. A feeling of compassion, of affection, of love followed. Memories of childhood, the importance to dream and to use one's imagination, allowing us to become our own architects of wonders. Let yourself dream. Shake up the ‘younger you’ hidden in your own eyes and past. The one the world tells you to silence and forget too often. Do not let that little guy disappear from your life. It's about having fun, smiling, playing. Keep that spark burning like an eternal fire.

PS — Yes, I love that.