Barbie Girl

So, tell me about the show.

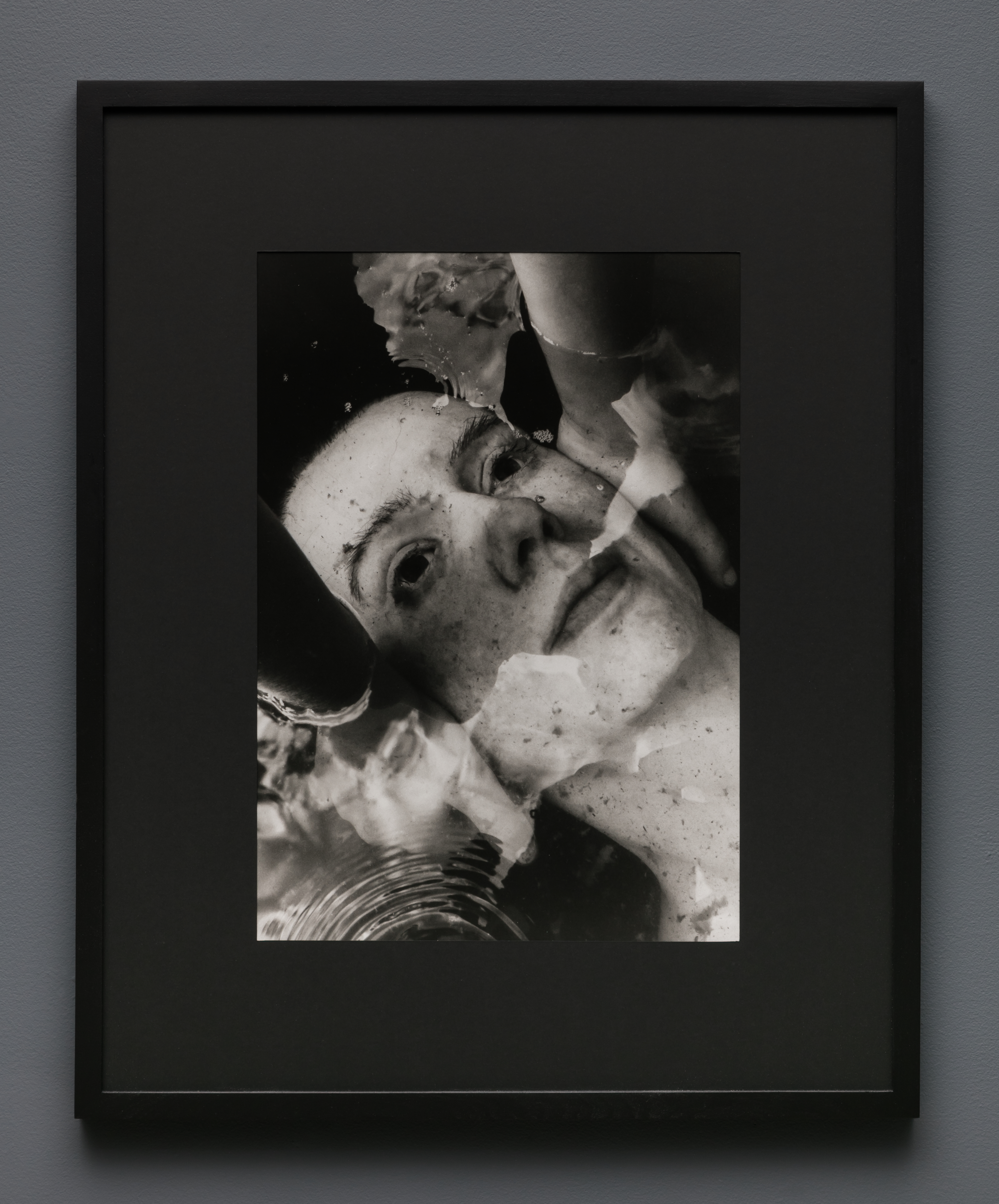

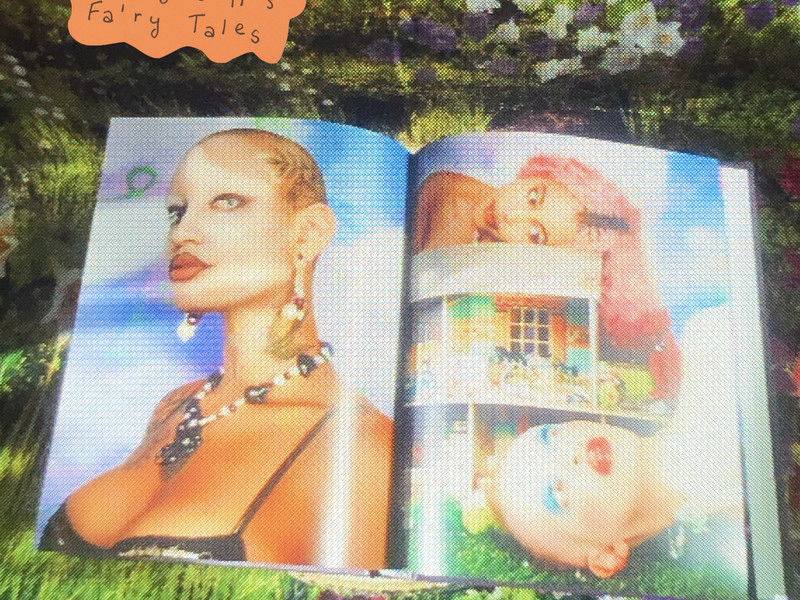

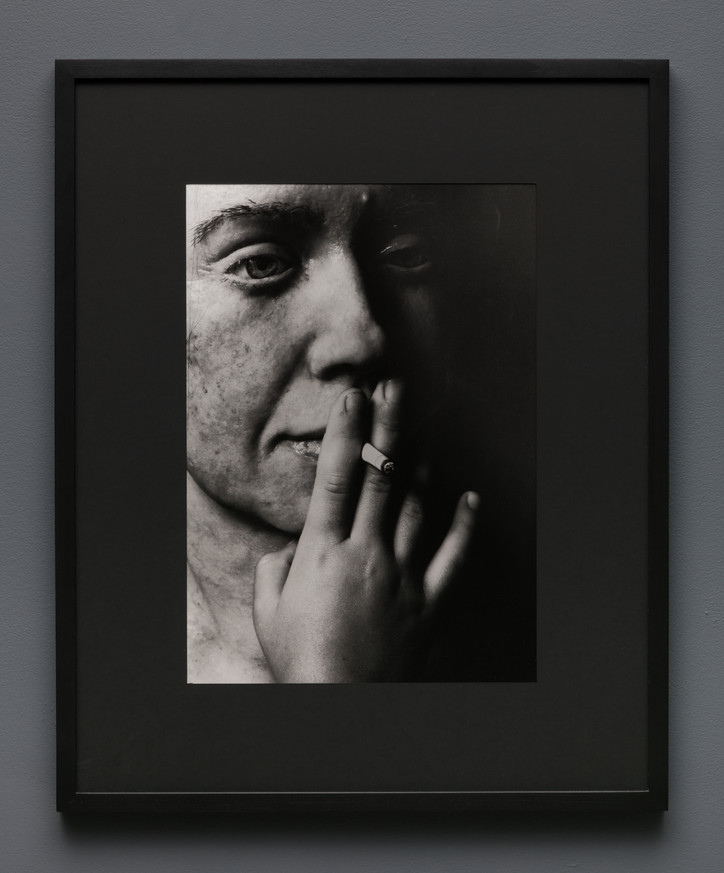

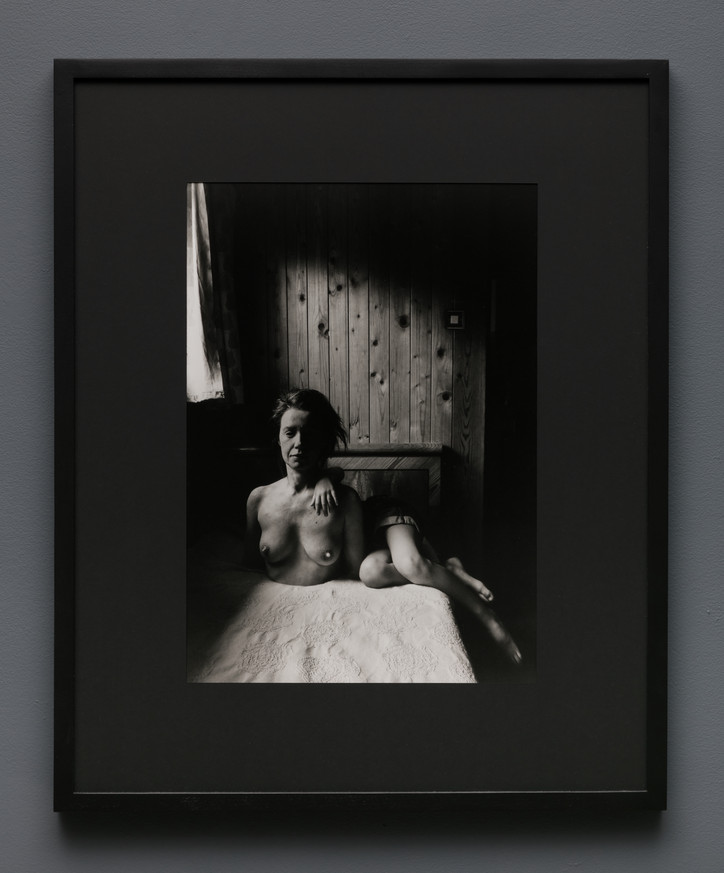

So, there are two series of works, the first one is ‘Beauty Masks’ showing me posing with the masks which I bought in regular shops—masks used to make us beautiful. It’s quite interesting for me that these real objects are used to shape the body as if it were a sculpture. I use it in my art but, of course, people use it in their normal lives, and this subject was very interesting for me—where art is something very similar to real life, to our contemporary situation, why we shape our bodies to make them ideal and beautiful. Of course, this aspect is full of violence. Sometimes the shaping of the bodies is very strong in order to change us. As you can see, these masks are like costumes, which I wore and in fact change my identity.

And these are all used in the beauty industry?

Yes, they’re all designed to preserve your beauty for longer, it’s interesting. In my earlier works, I was using clothes to change my identity—in 2006 I made a repetition of a very famous Cindy Sherman cycle, her untitled film stills, and here it is the same but it’s with regular things.

Where did you get them? I’ve never seen some of them.

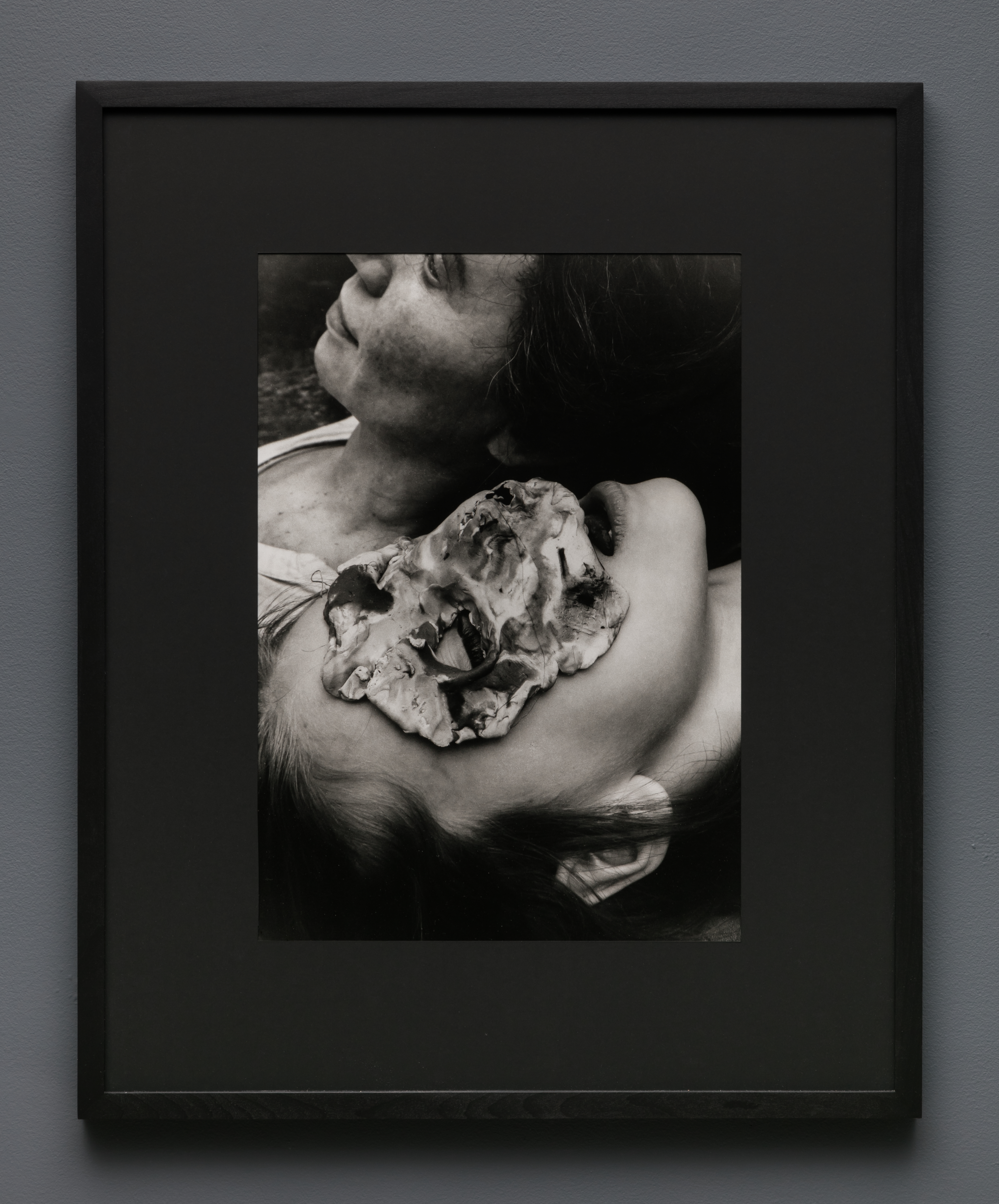

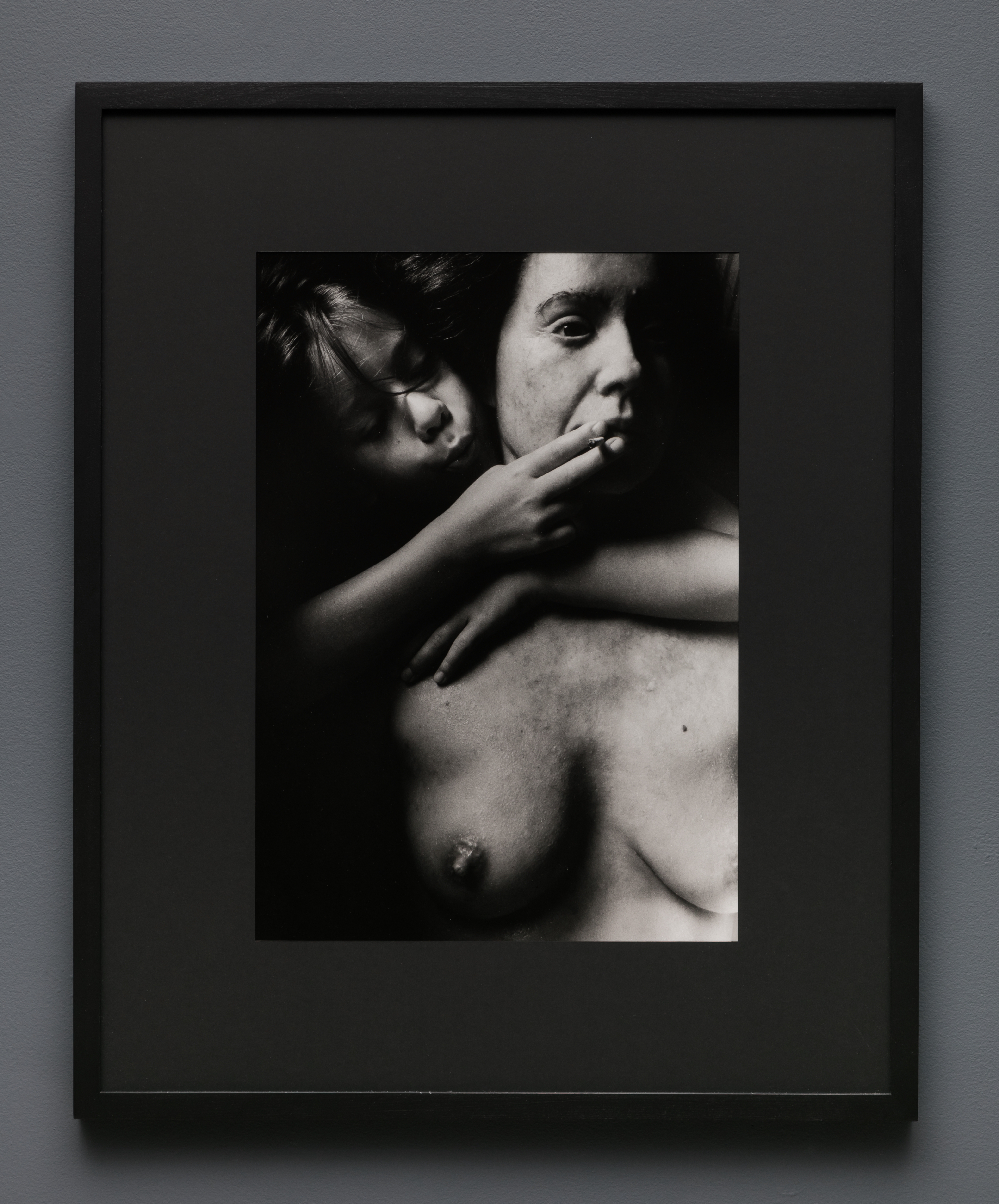

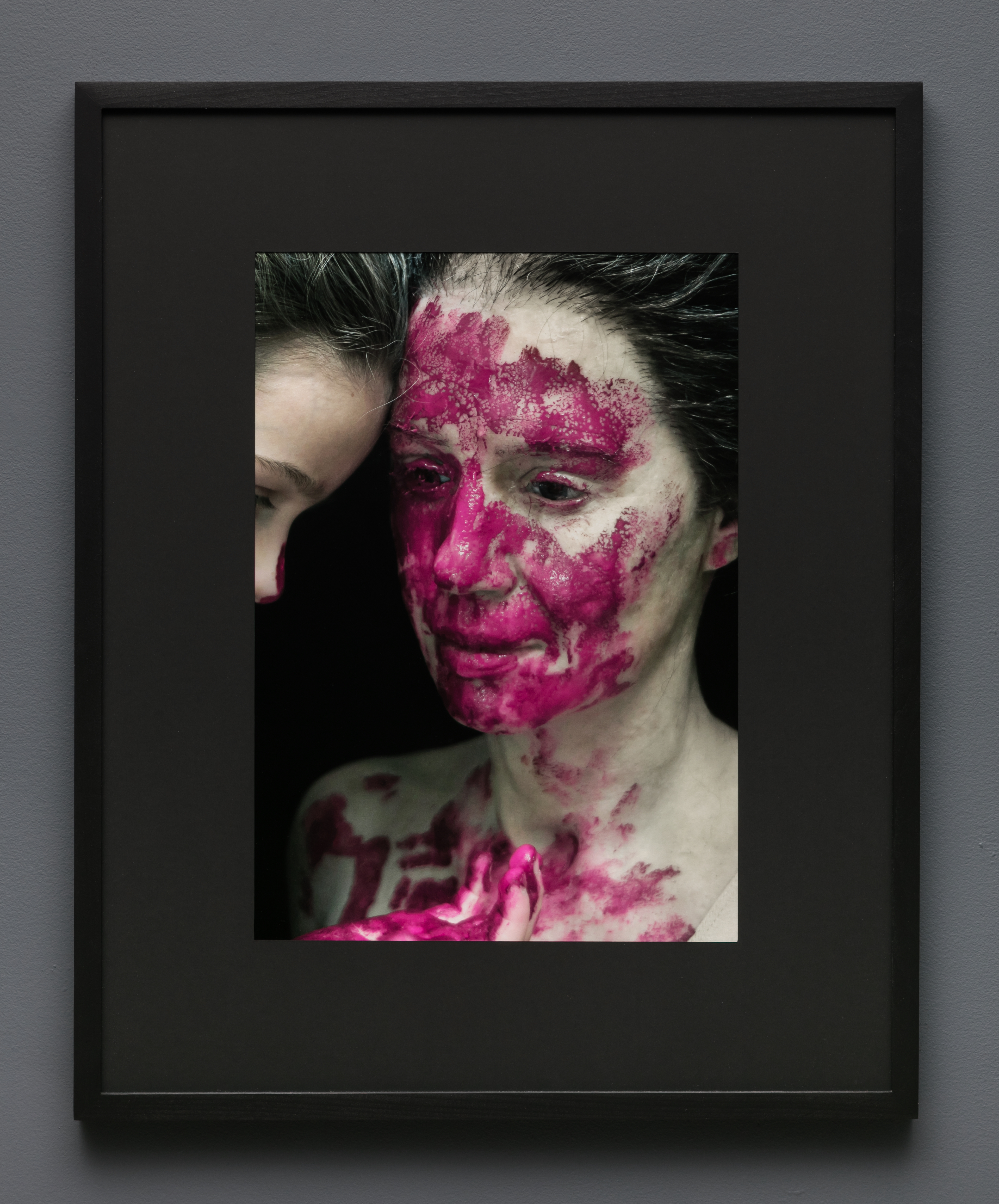

Just around, it’s possible to find them. This series is shot together with the newest series of photographs I made, the title is ‘Mama,’ and the point is that I ordered this sculpture, this object, which is in fact a copy of me. It is a doll, like a hyperrealistic sculpture showing me and I gave this doll to my daughter to change the situation, in fact, because as you can notice today, we’re from the youngest age, because children play with dolls—there are both kinds, there are babies that they can take care of, or Barbies, which are the imagination of their future, their ideal—and I don’t like this kind, because I think it’s shaping us from the youngest years. It’s a similar situation to the beauty masks. So, I made a doll which is in fact the mother, and I took the series of photographs along with my daughter to play with this doll.

Can anyone order this doll online?

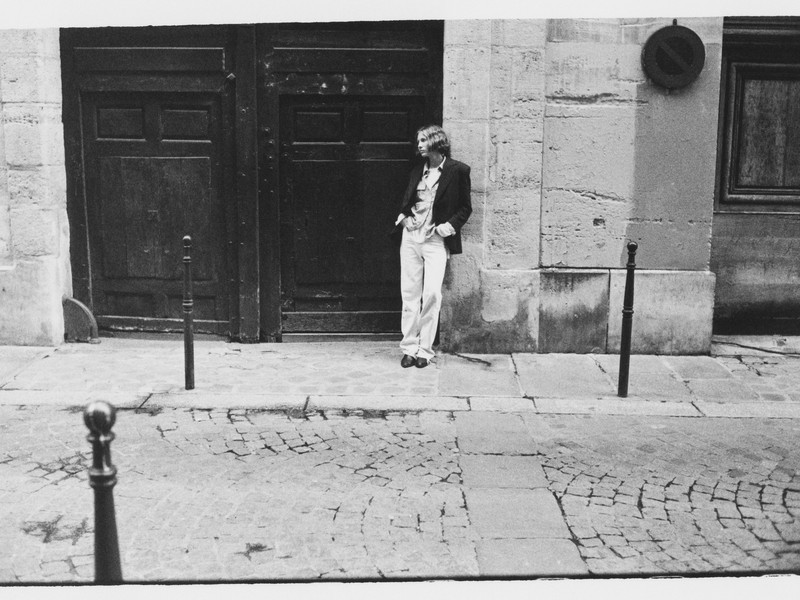

No, no. It was prepared with me by a technical artist. As you can see, the photographs are in two colors, black and white and color. I decided to do it this way because, in fact this doll doesn’t look very real in reality, but it becomes real when it’s photographed—so I was trying to find a relation with this medium, and the black and white photographs are paradoxically more real than the color reality.

So, you’re trying to make the doll look as real as possible?

I was testing this, because as you can see the frame is very narrow, so it’s not visible that the doll is, in fact, cut, and this is only part of it. The way it’s cut it constructs the body with the body of my daughter so it mixes all together.

They’re kind of scary.

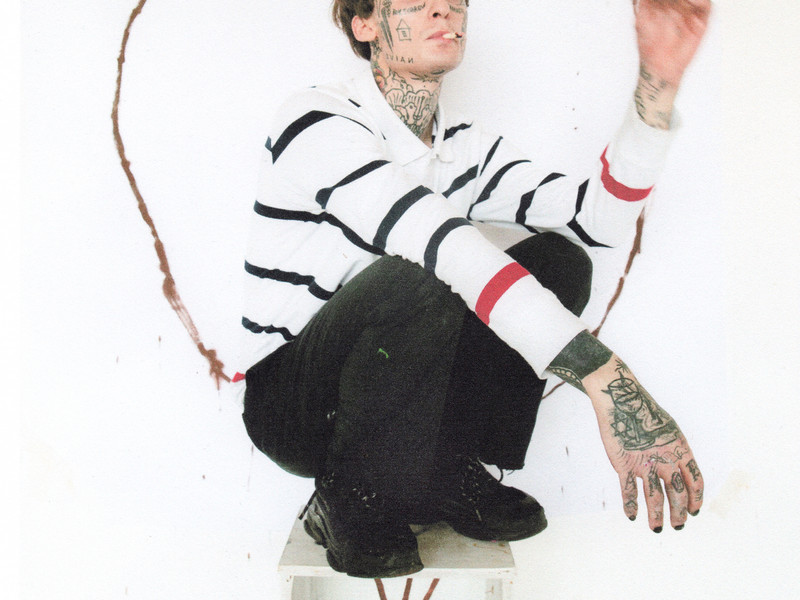

I think all of my works are balancing between scary and funny, absurd. As you can see here, you have the narration, a kind of circle which can be repeated over and over, because it’s like using real life to prepare a kind of movie, let’s say. So, my daughter is playing with the prop in a kind of movie which we created together.

So, did you just let her do whatever she wanted and you followed her around with a camera?

Yeah, but of course at the end I wanted the feeling of the narration, so I added some additional photographs to create this circle, to build the story.

How did your daughter feel about it—it’s kind of weird, right? Did she like it?

She’s grown up in an artistic family. In fact, this doll was photographed in the countryside and her friends were there and it was, of course, a huge attraction for them, too. You must remember that what you see here is the final effect, this performance while it was photographed was a bit different, so here it’s playing with the emotions of the viewer more. And you can see not all the pictures are scary some of them are just funny—I try to balance these two.

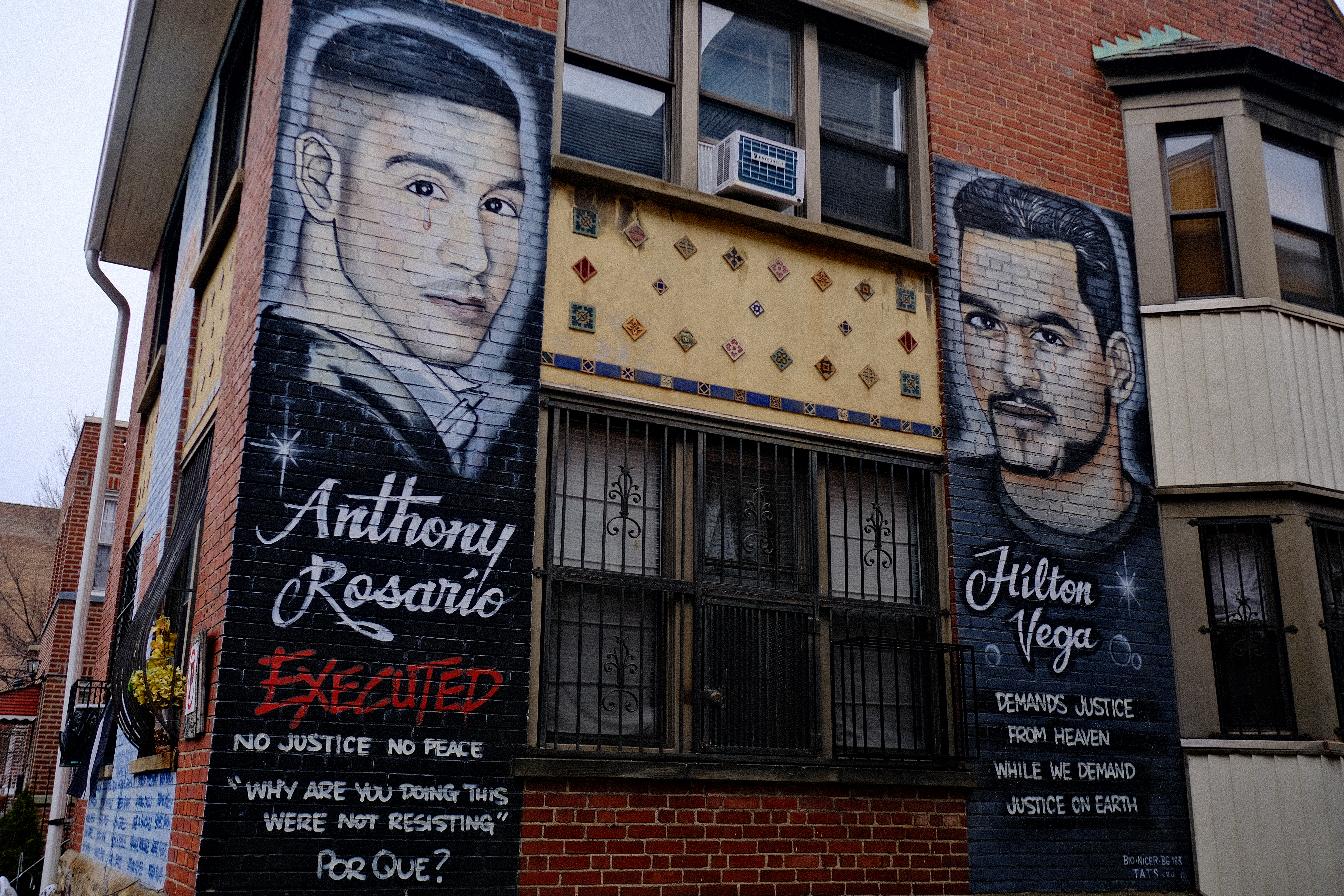

I think the very important thing here is a feministic context. As I said before, it’s about this shaping of children into a special role they should have in the future, and I believe it’s necessary to change these roles, it’s like a metaphor of building a new world, of women in the future—they can somehow destroy us to create a new, stronger woman and this Mama here is the symbol of today, let’s say.

It’s like you are the doll, you are Barbie.

Exactly. And she is supposed to change my position, and our position—which is what is visible in 'Beauty Masks.'

Did you have Barbies growing up?

I dreamed of having a Barbie.

Does your daughter have Barbies?

No, she doesn’t play with them. But I grew up in the Communist period in Poland, it was very strange, and I was dreaming about Barbies so much that I woke up and was sure that I already had one, but it was only a dream. There’s a well-known series by a famous Polish photographer made in 1974 when the artist’s son was born, they made this series of photographs of him with different objects in their apartment—but they were so strongly connected to their art they wanted to use their child in their art, and here I’m putting my daughter in the situation as subject and she is in fact the co-creator, the co-author of these works. It really depends on the viewer on how you treat these photographs. From a child’s perspective, it’s just play, and from the artistic field it’s a performance using a sculpture, but for my daughter it was both. It’s also asking what art is—art can be everything. Regular play with a toy can be art, depending on how you treat it.

Where is the doll now?

In our apartment.

Did you think about physically including it in the show?

No—I really can’t speak to the technical details, but it really doesn’t look like this in reality.

So, there’s a kind of magic that the photos lend it.

I’m not sure it’s magic, it’s the medium of the photograph that makes us believe in it. It’s also the subject of my research—I work mostly with photography and film, I treat both mediums as the medium for making a documentation, but this is in fact not a documentation at all. It’s about the experience between reality and the artificial.

Part of why the doll is so striking is because it looks dead—do you feel there’s a play with life cycle and death?

I think my works have this very existential research to them, I’m very focused on it. This is the object, and it’s compared with the human being, so somehow it’s more visible because even photographed from different perspectives, the doll’s emotions never change—it’s the daughter who gives the doll its emotions, and the emotions for the viewer. For me, being a mother is something very existential, because a daughter, especially a daughter, is someone with whom we identify, it’s like our future, even if it’s another person. So, I must admit that my identification is with my daughter here, not with the object.

It’s cool what you said about the emotion coming from the daughter, and how we project onto our toys—we give them life when we play with them.

Exactly. As you can see here, for example, the mama doll is among other regular dolls.

Does your daughter want a doll replica of herself?

Actually when she was born, she became the most important thing for me and I started to put my interest on her. She was very small and I would make sculptures the same size, human-size sculptures. Before she was born I was making a lot of self-portraits, but when she was born that stopped being important, I wanted to make her, but she was so small that I started working on what I imagined for her in the future, so when she grows up she can compare what I imagined with the reality. It’s an interesting story—but it’s also all about being a parent, how this human we created is shaped by us.

'Mama' will be on view through November 18 at Lyles and King.

All images courtesy of Lyles and King.