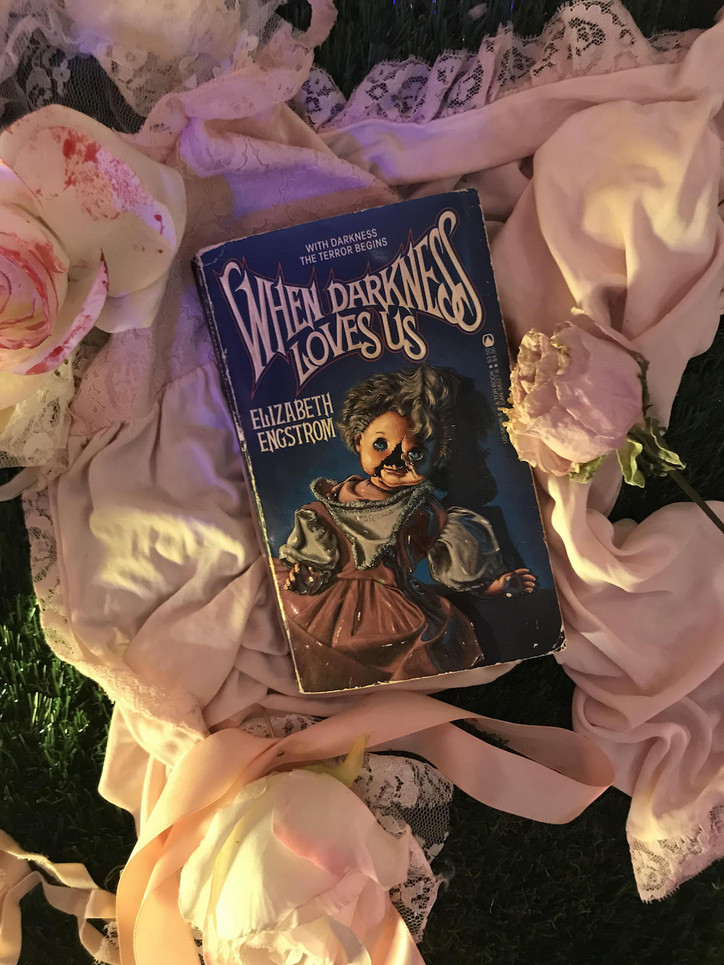

The Bennett Sisters Aren't Afraid to Die

Juxtaposing the dramatic and darkly hilarious work of artists Parker Day and Robert Hickerson with more analytical and meditative pieces by Maggie Dunlap and Linda Friedman Schmidt, the sisters construct a fuller vision of what dying means––for the dead, the living, and the crime-and-death-obsessed public eye. The floor of the exhibit is blanketed with green astroturf and mini-memorial sites, imitating a cemetary. And since we all have to die someday anyway, we might as well take inspiration for our own graves from When Darkness Loves Us.

office sat down with Rémy Bennett to talk about the thing nobody ever wants to talk about––the inevitable end.

Tell me about the work you and Kelsey chose to display in When Darkness Loves Us.

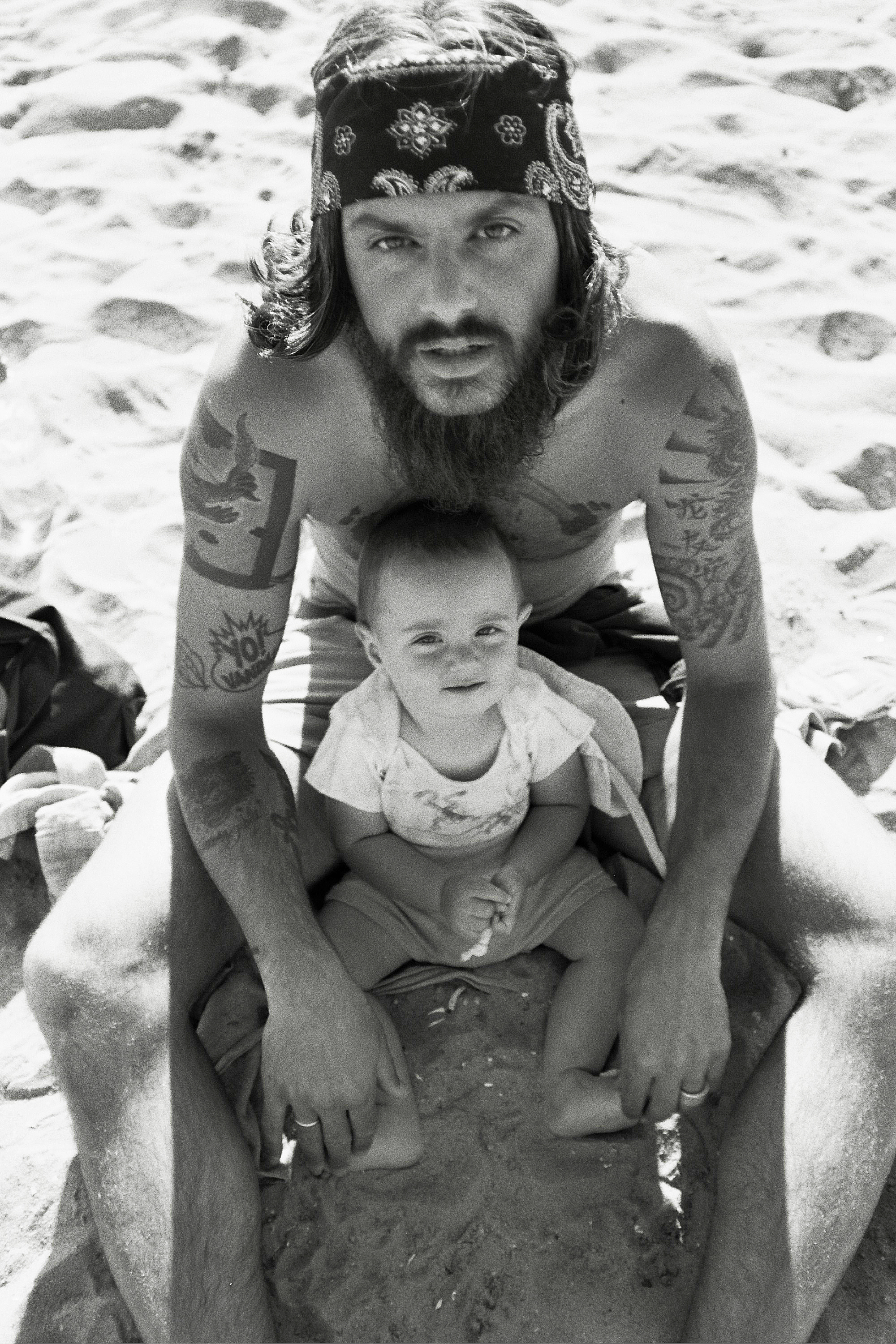

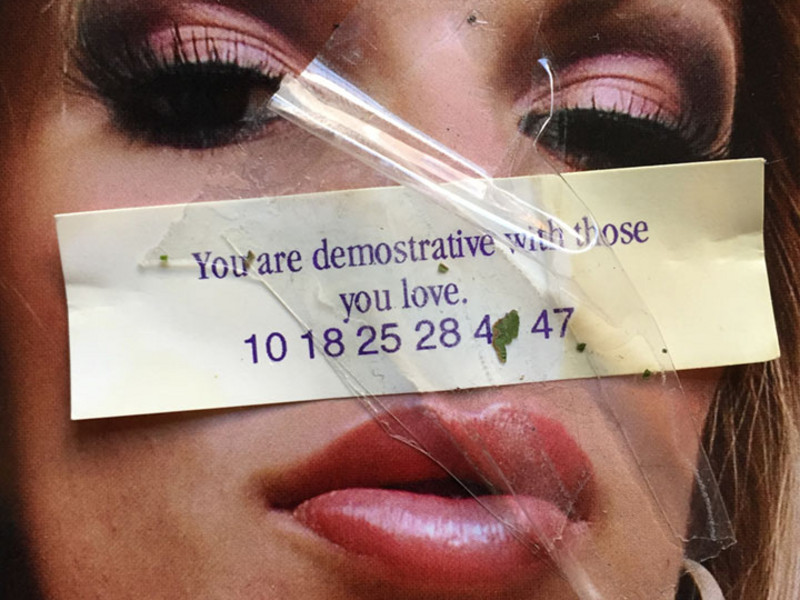

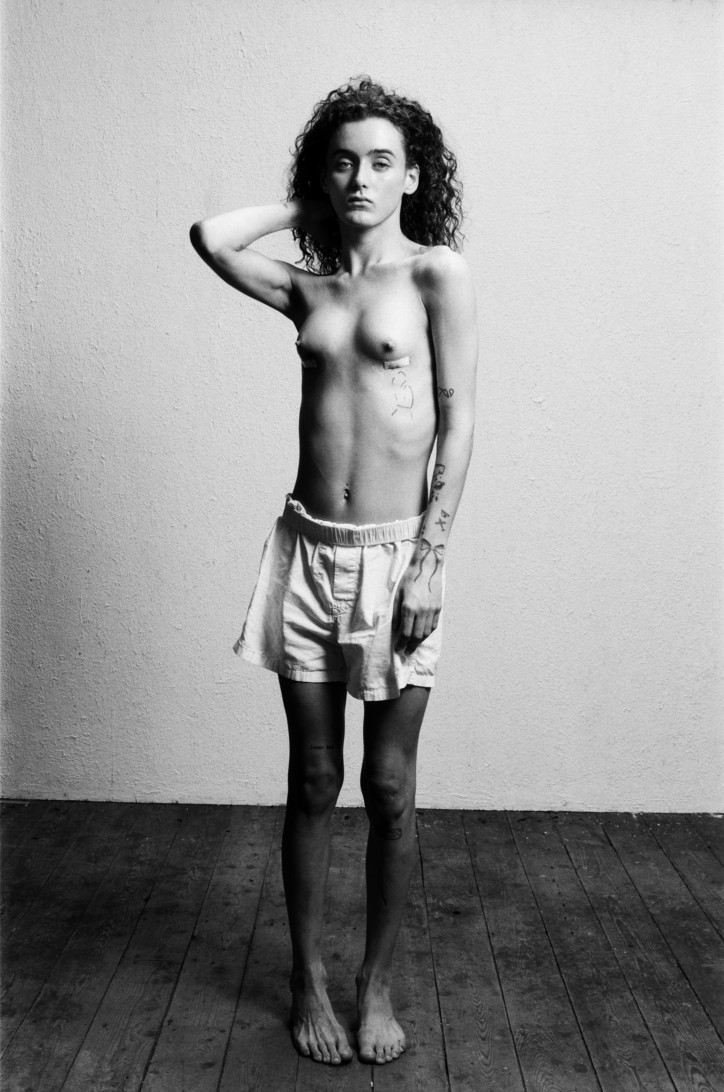

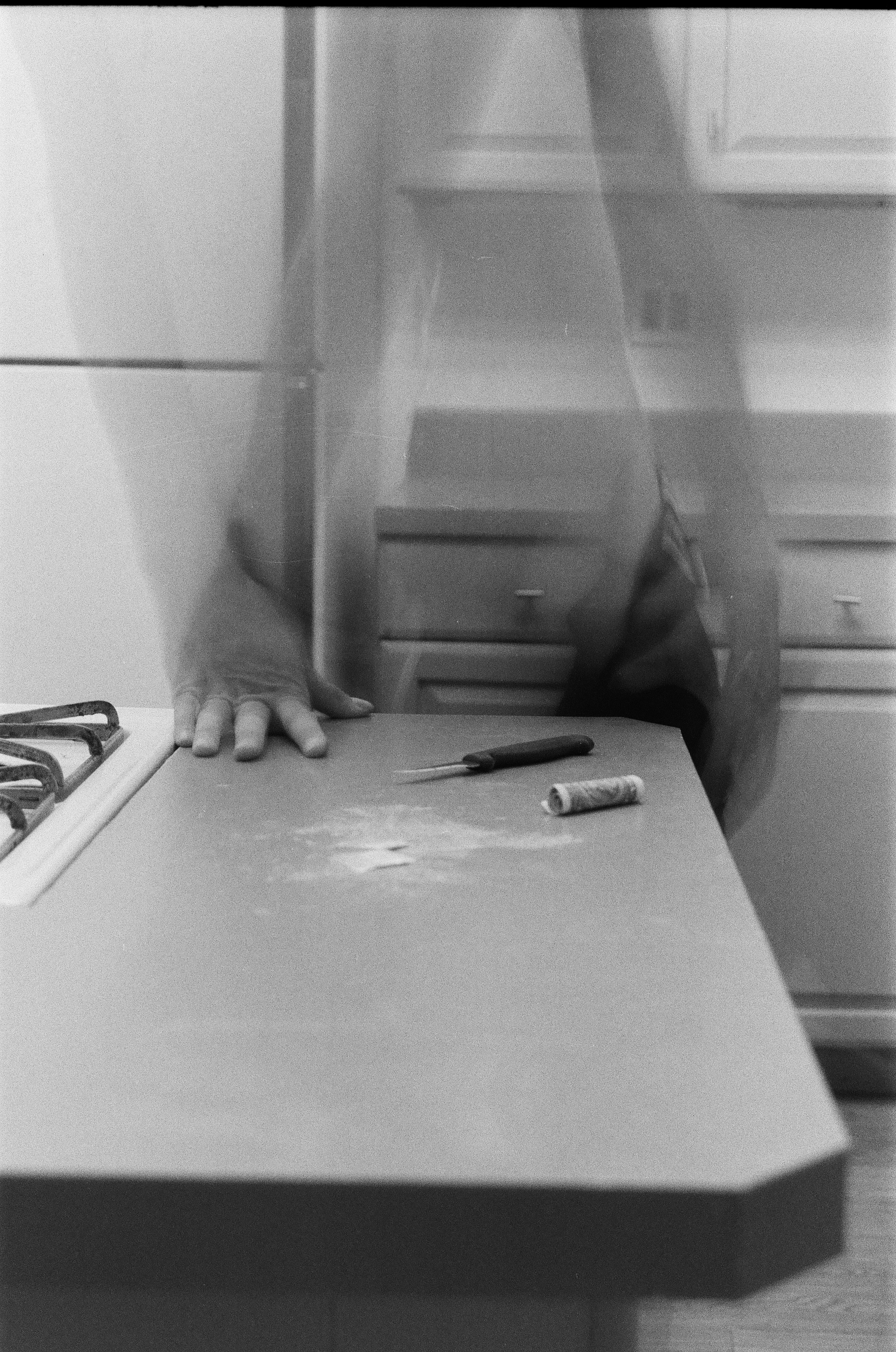

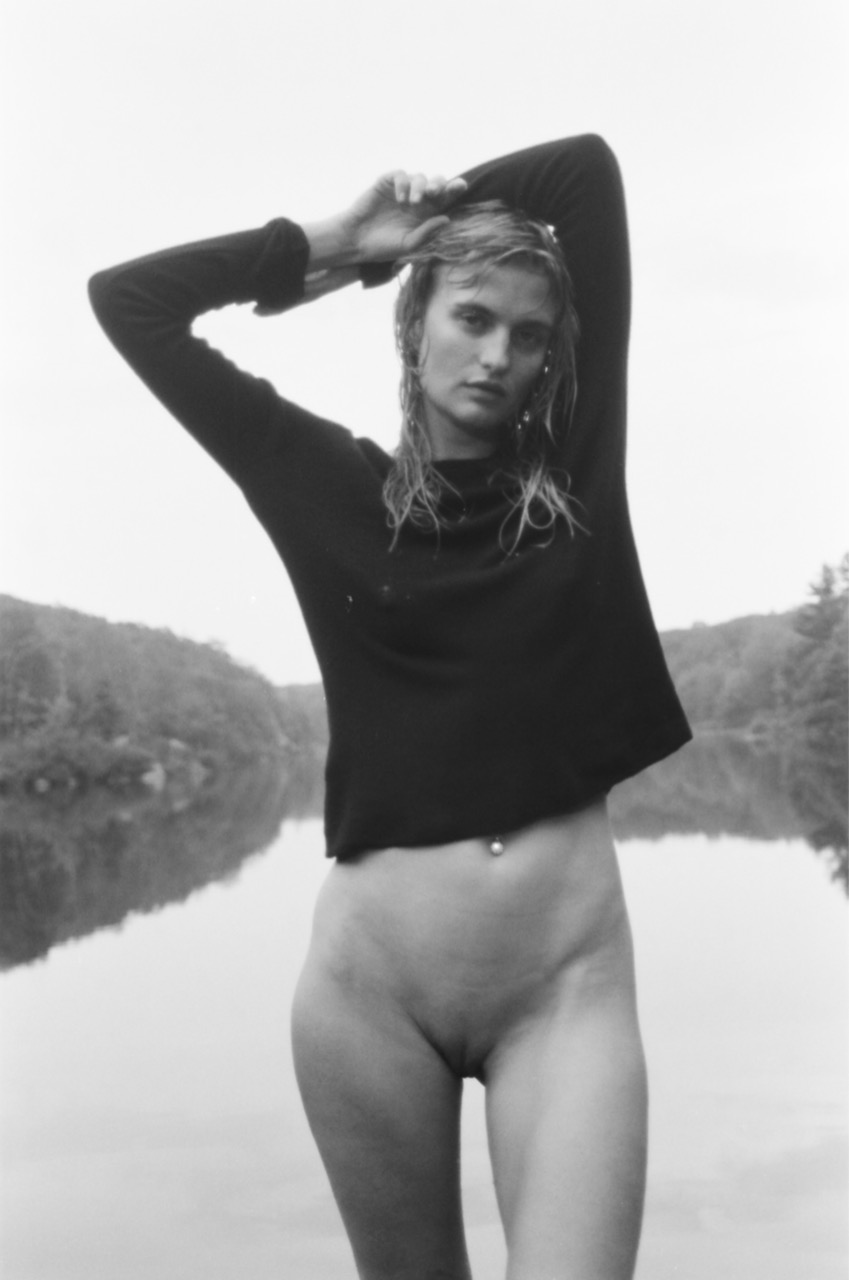

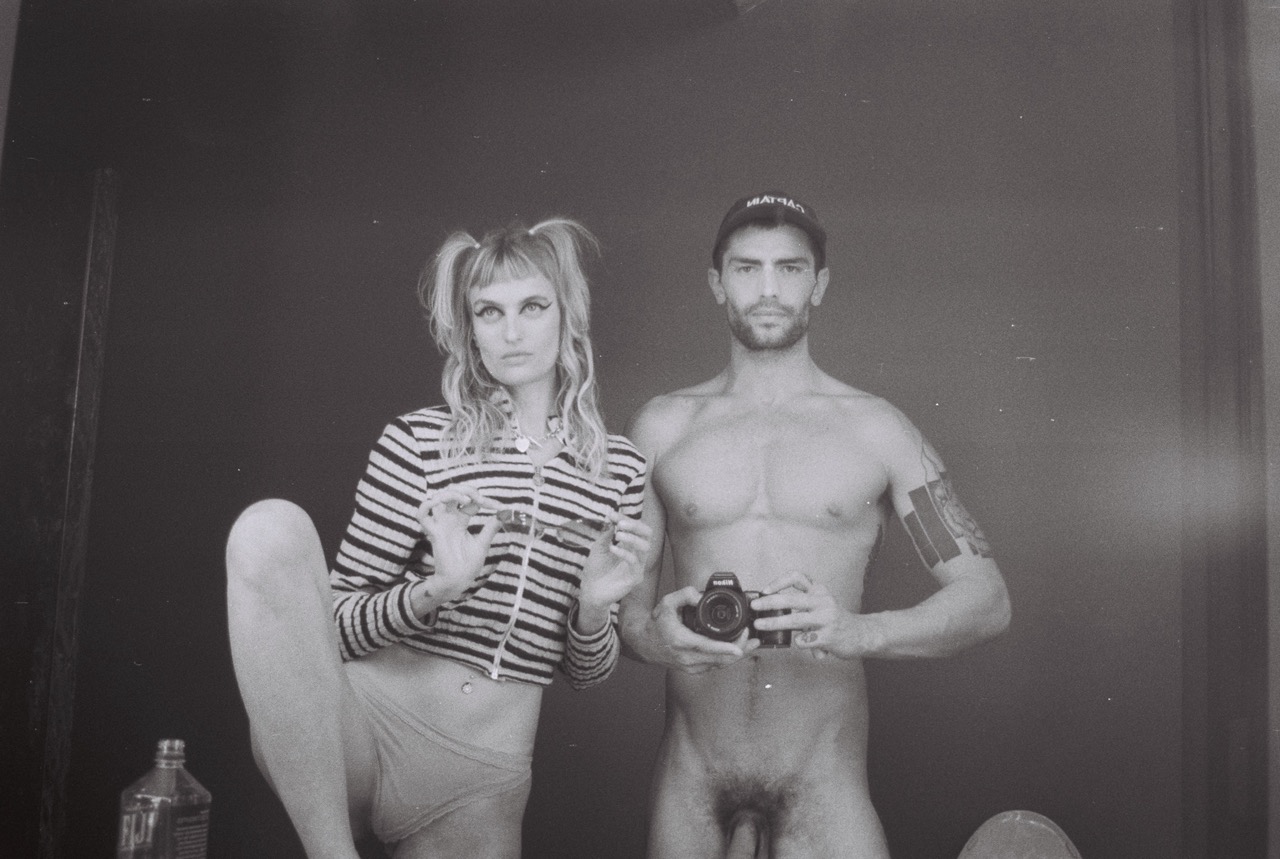

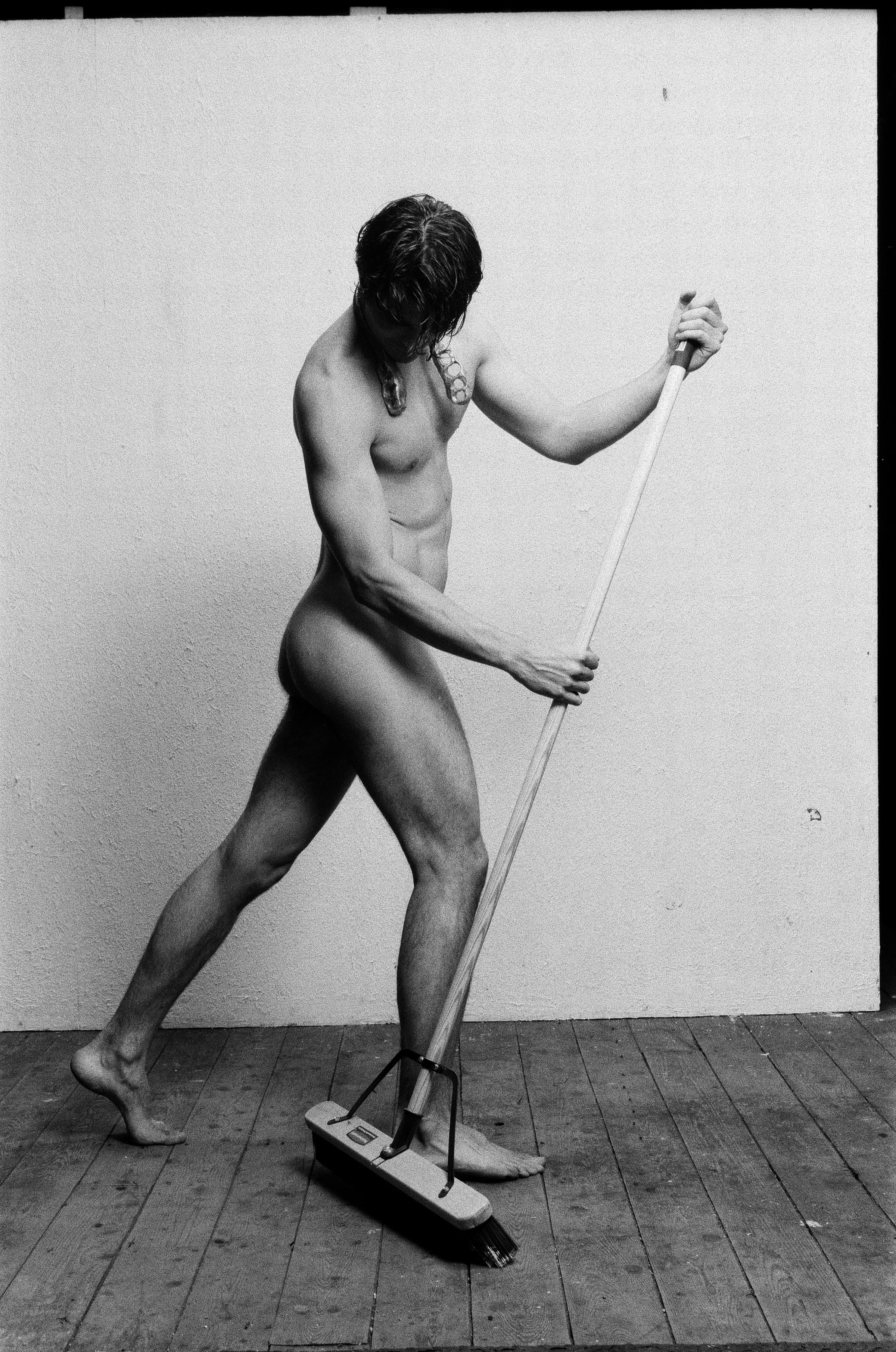

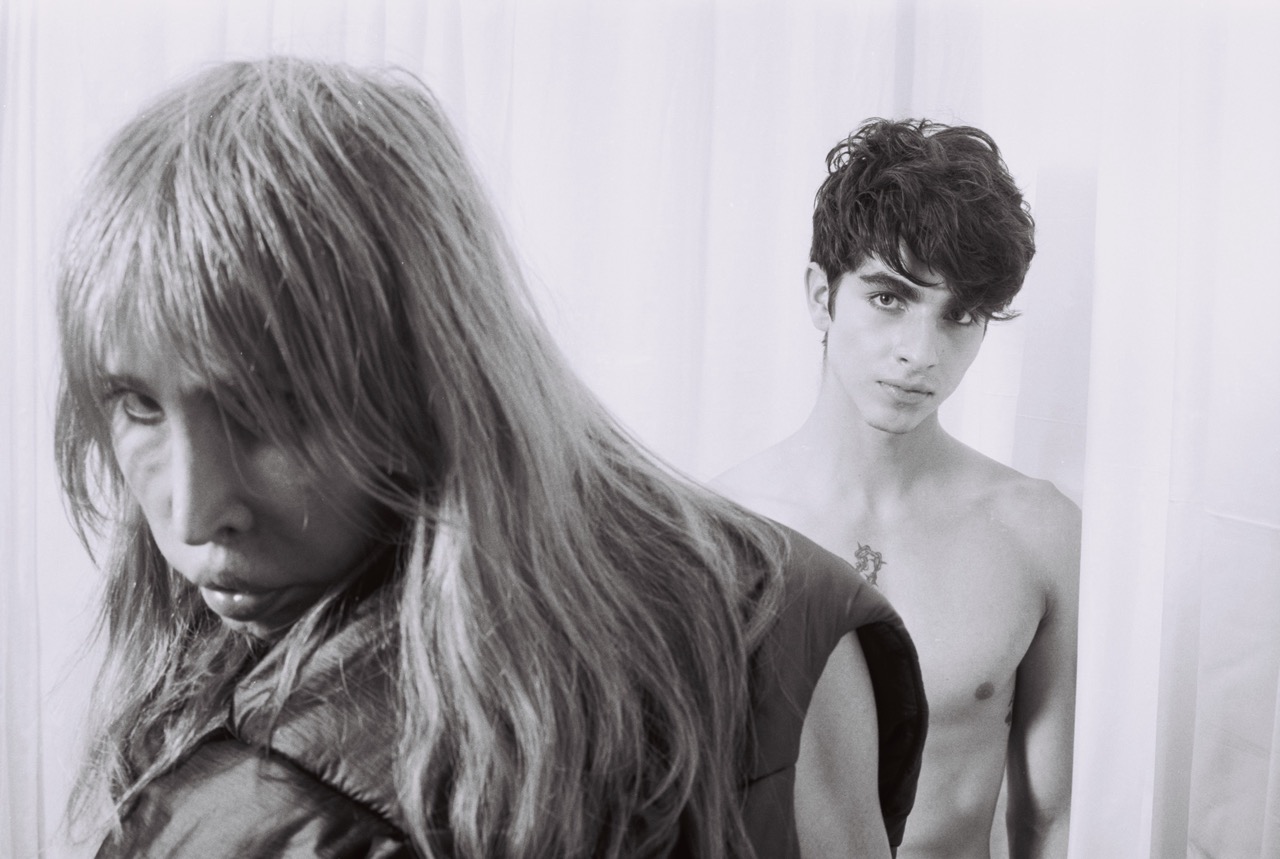

There’s a sense of irreverence that’s strong with all the artists we’ve chosen––they’re depicting content that’s what people would describe as “dark,” but they embrace it is in this anarchic, visceral, joyful, funny, extreme way. It’s that sort of anarchic teenage spirit. We talked about the idea of harking back to being an adolescent discovering things you shouldn’t be, that give you this sense of titillation and exaltation.

What did you get to do in curating this show that you haven’t in the past?

Incorporate older artists, and realize how much they can teach us and the humility they can offer us. Linda Friedman Schmidt [who’s 68 years old] has become a really close friend and inspiration––her work examines more of a personal process of grieving. The artists in our show are all sensitive people with very lurid interests, so we’re explaining both sides of the coin. We’re not just going for the satire or irreverence, we’re trying to bring our audience to a bit of a deeper place that makes you feel sad.

How would you describe the theme of When Darkness Loves Us?

The theme of the SPRING/BREAK this year is “Stranger Comes to Town,” and for us it was like, the idea of death is universal. It’s literally the only thing in life we know is going to happen. It can be left unsaid, but it’s collective. There’s something about coming together and having a collective celebration and also a meditation on how hard it is to grapple with it. It’s this existential crisis that we all have to face, but if we all talk about it, what kind of positive forms of expression can come out of that? It’s about catharsis in a lot of ways, and acceptance.

Which is your favorite piece on display?

I don’t want to leave anyone out but something I’m really excited about is Ambre Kelly and Andrew Gori’s [screenprint] series, “Forever Michael,” which is about Michael Myers. That’s something that I’ve been dying to find a way to exhibit for years. I’m proud of that piece.