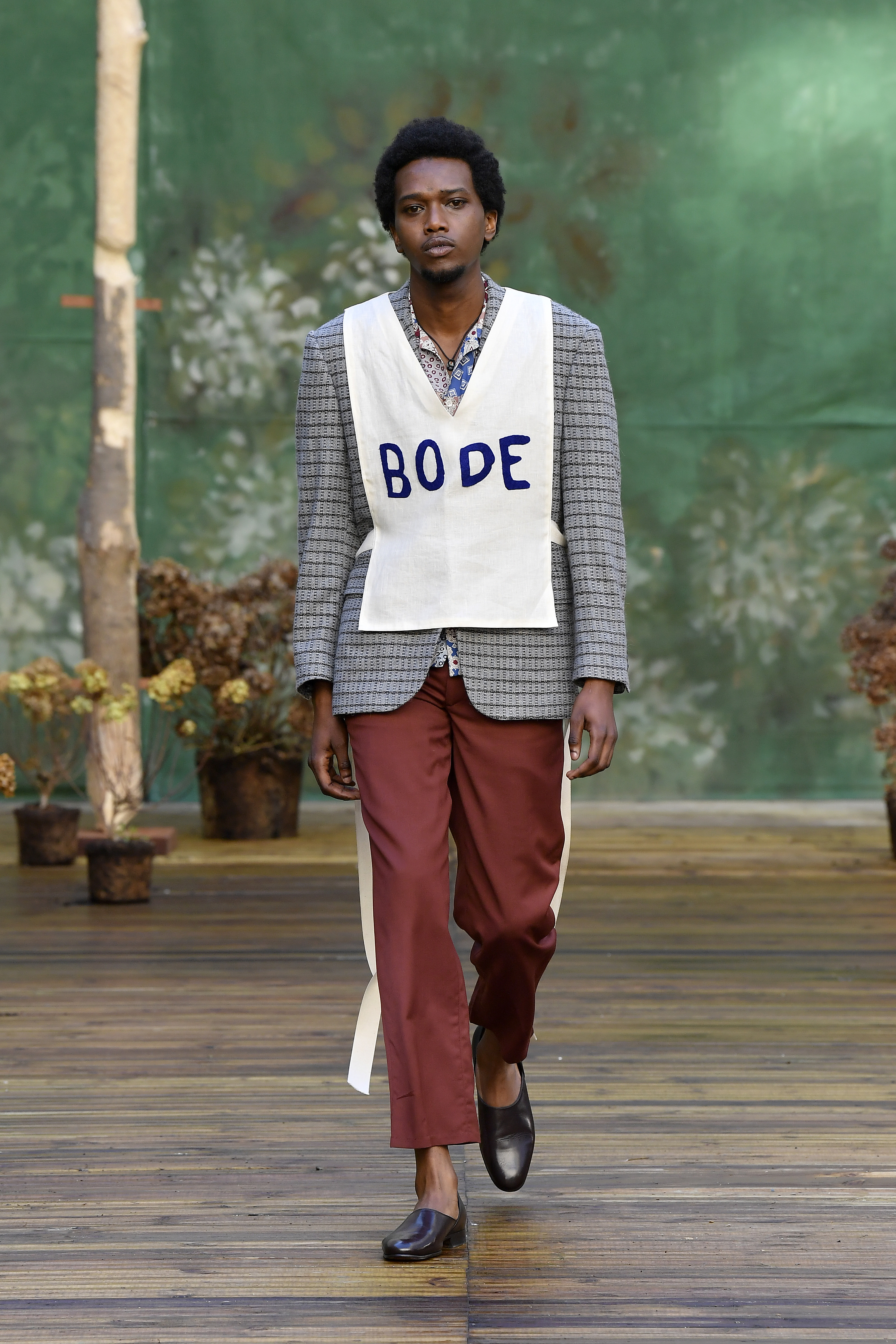

Bode F/W '20

As models walked amongst Bloomstein’s-created set composed of wood from Ash trees that were cut down by beavers on a tributary of the Green River, the artist’s impact and adoption in Bode’s F/W ‘20 show felt entirely omnipresent.

Stay informed on our latest news!

As models walked amongst Bloomstein’s-created set composed of wood from Ash trees that were cut down by beavers on a tributary of the Green River, the artist’s impact and adoption in Bode’s F/W ‘20 show felt entirely omnipresent.

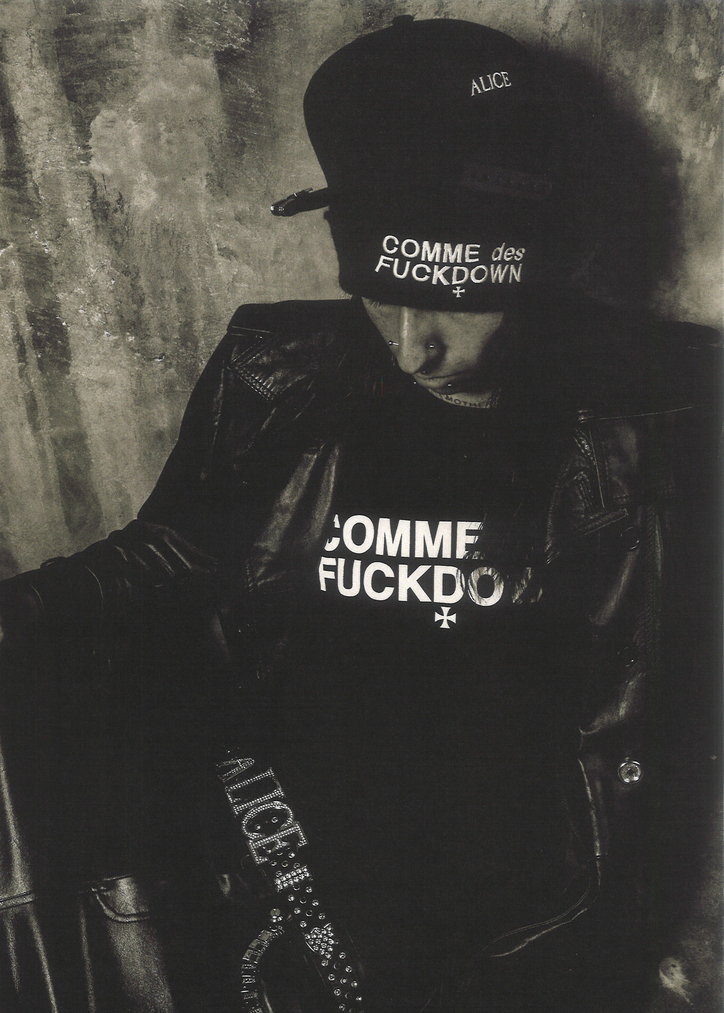

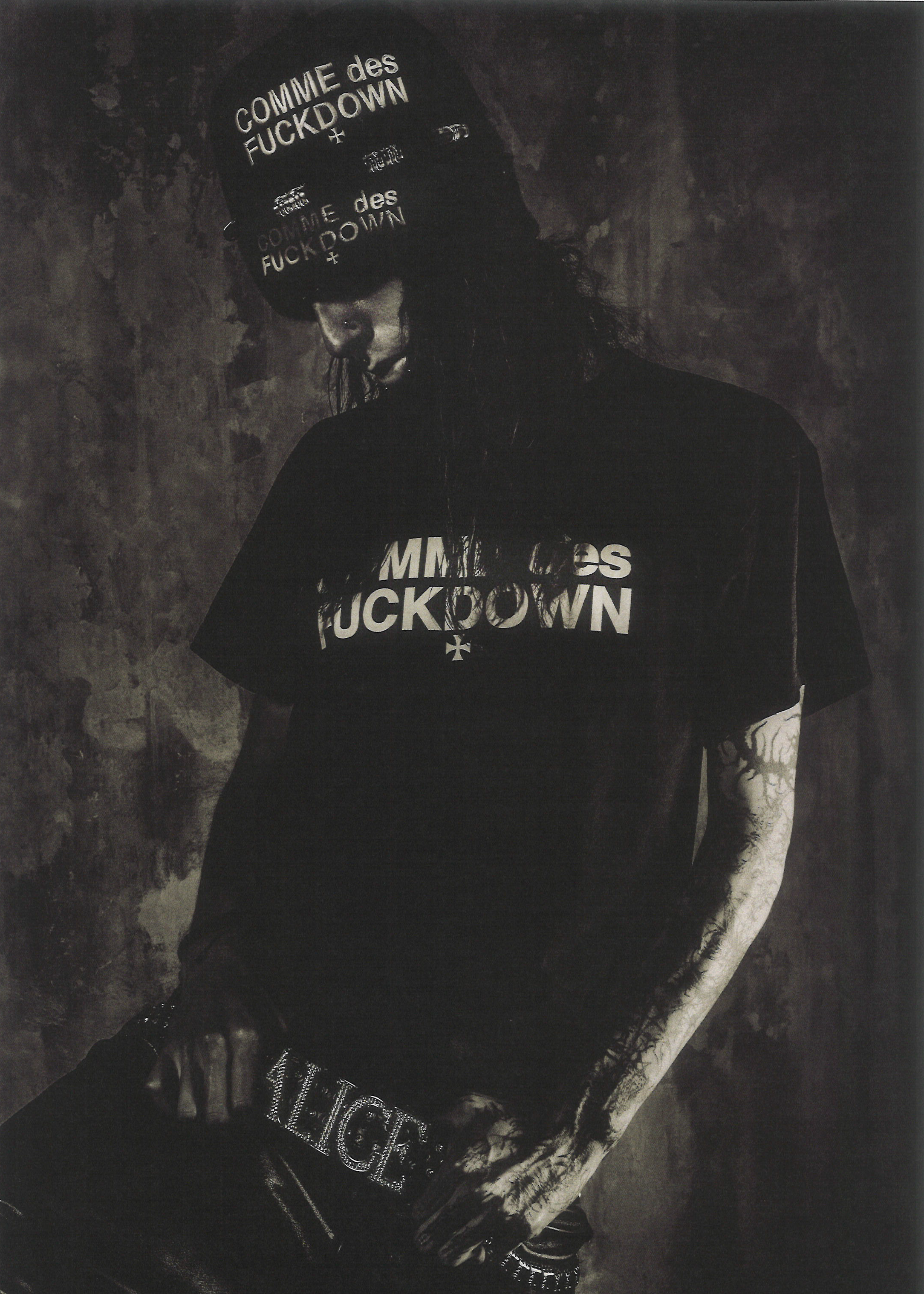

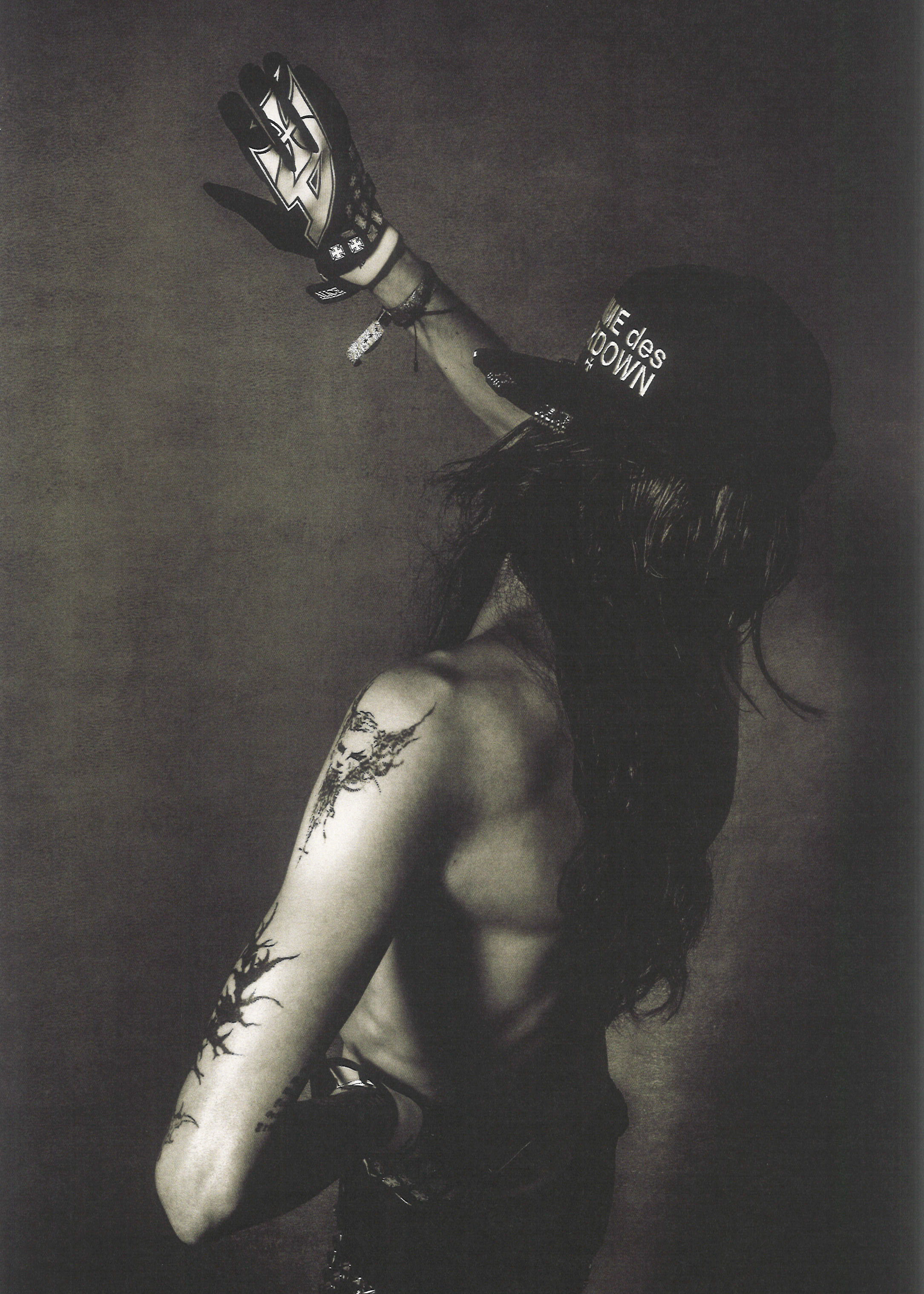

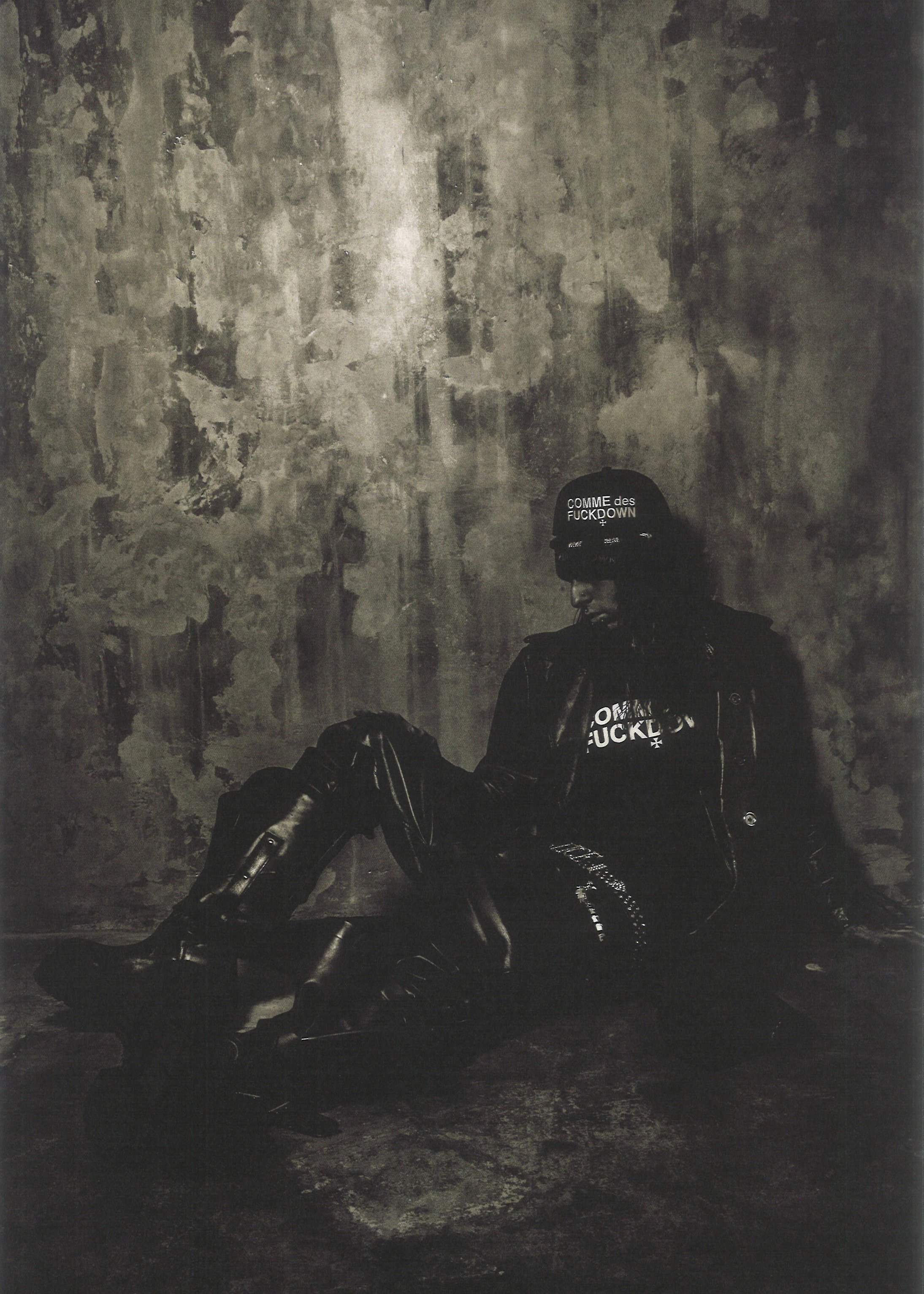

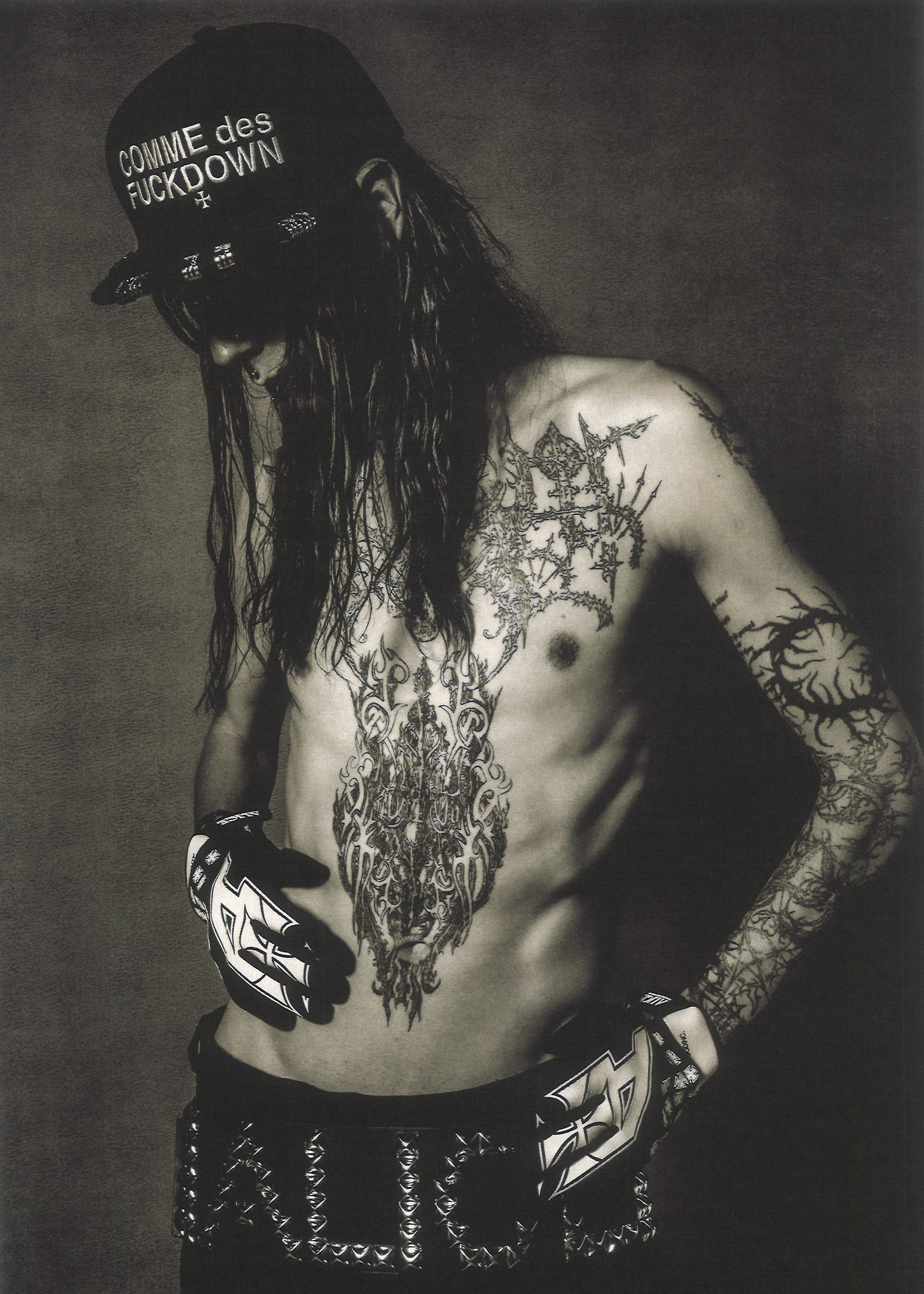

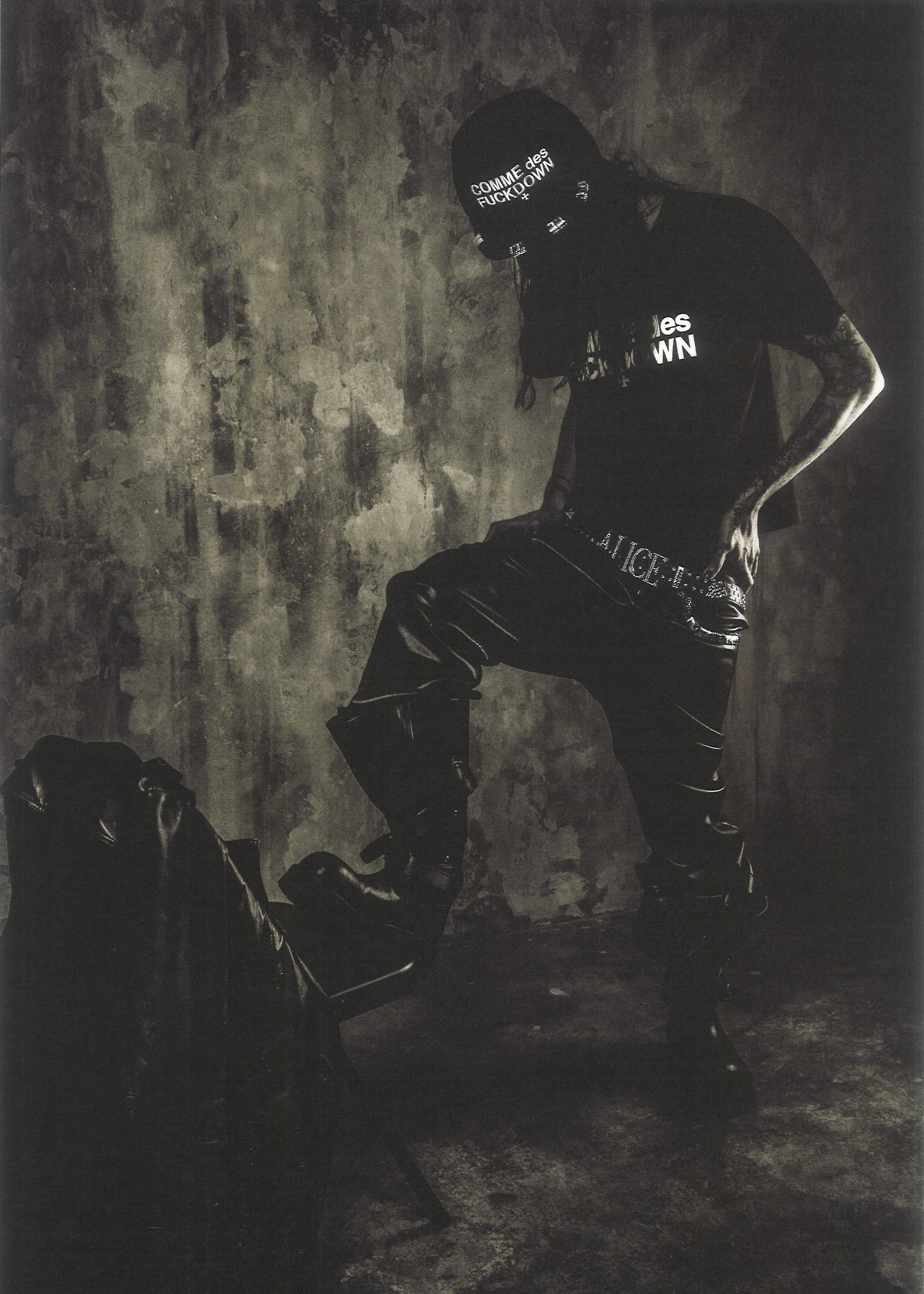

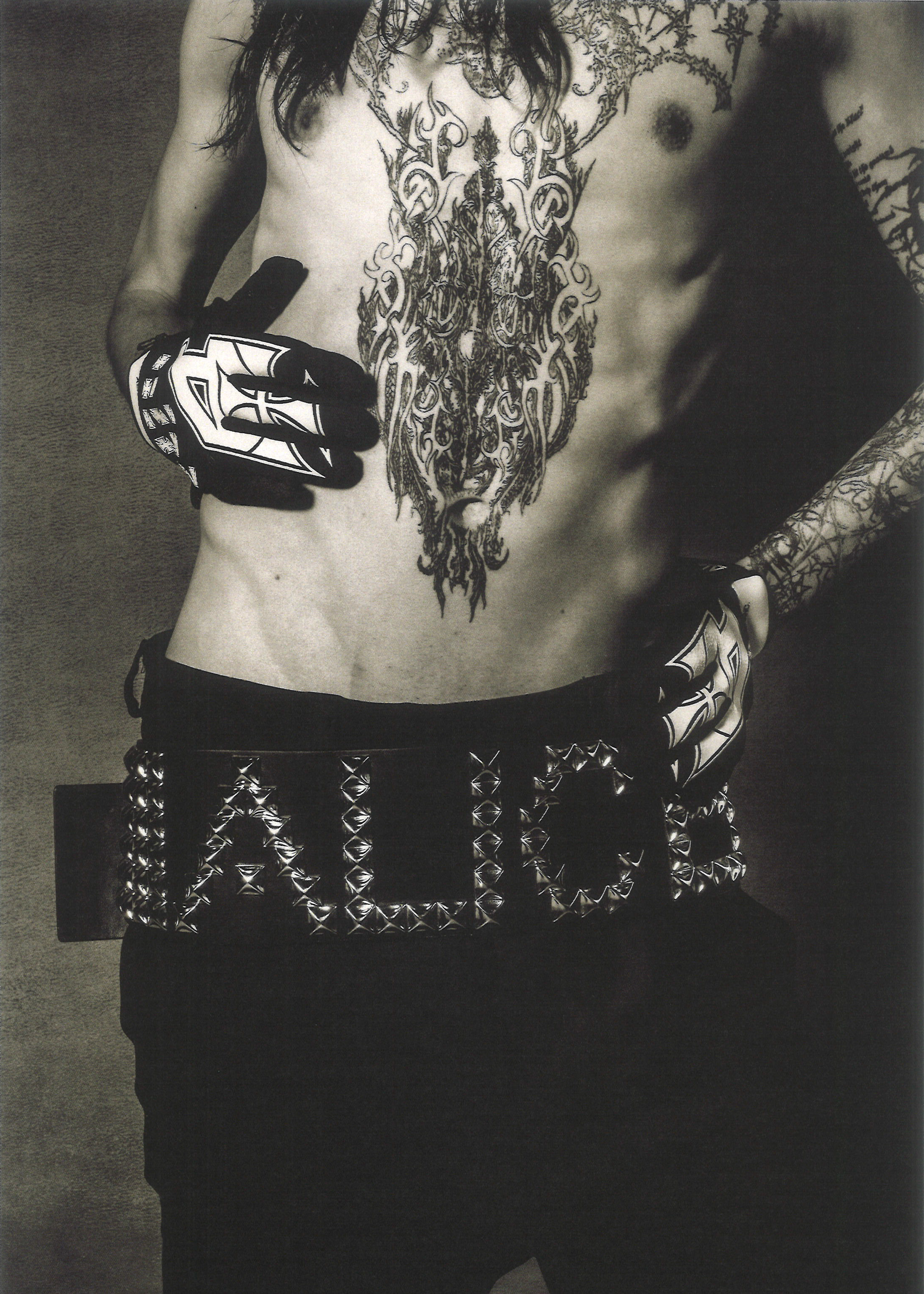

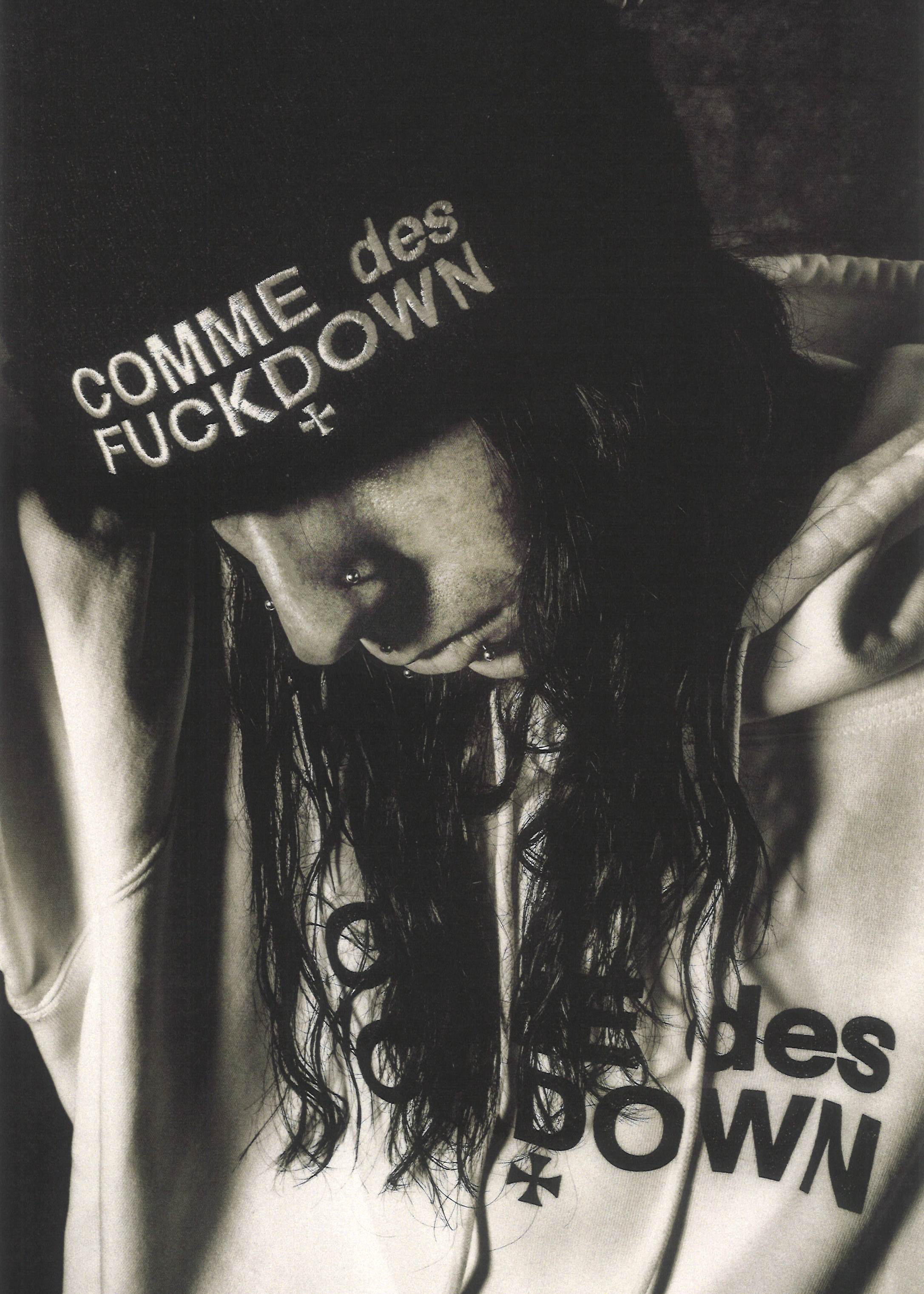

Launched earlier this year, Alice Hollywood is Gonzales’ return to his roots — not just aesthetically, but emotionally. “Alice is a clean slate,” he says. “Starting with SSUR felt like the perfect first step. This collection is for my 17-year-old self, and for a new generation discovering this iconic brand for the first time.”

The Alice Hollywood x SSUR — "Comme des Fuckdown" Capsule Drops today, Friday June 13th at www.alicehollywood.com and at the SSUR Odessa Flagship.

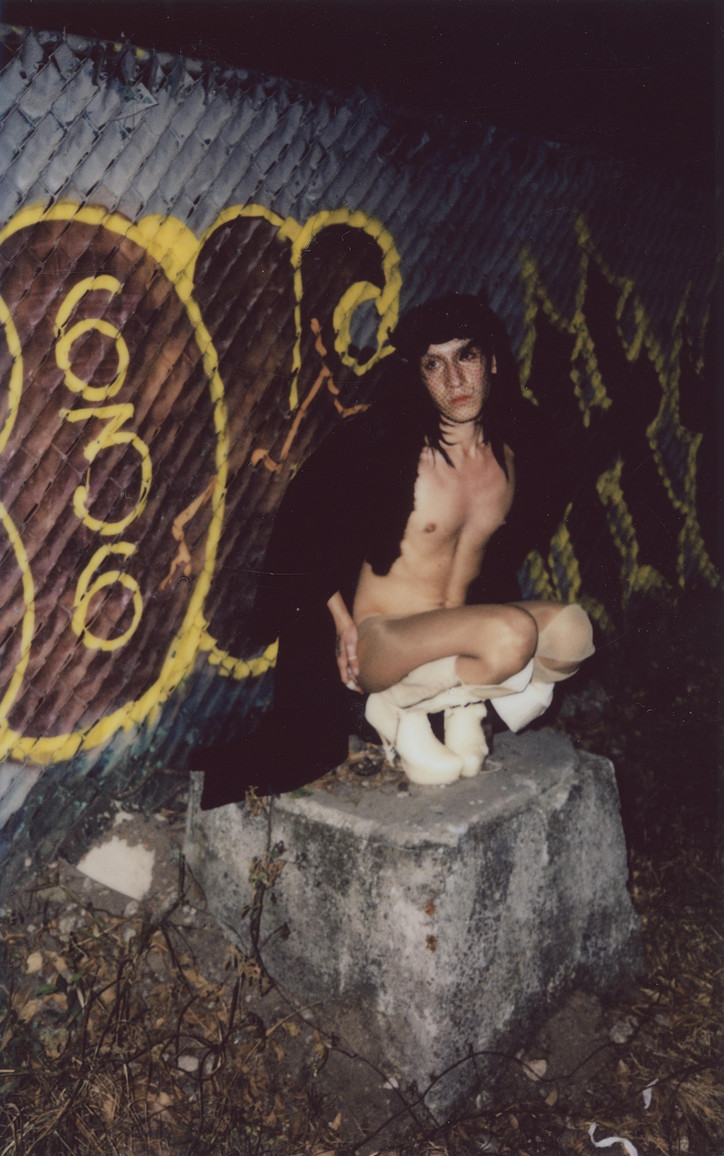

What made you create these images?

Mainly what motivated me to create again after so long was being trapped in a depressive loop, blinded by the violence I inflicted on myself, not the physical, the mental one caught me completely, my loneliness caught me, my sadness, my personal block, not only creative, my anguish, my addictions, my experiences I constantly repeated but I was saved by my hope that there is always more and that if you want it you can, to never give up and that if I don't achieve it nothing happens, that today I am and tomorrow I don't know, it doesn't matter if I am up or down, nobody is more or less, the important thing is to enjoy and love the process.

How do you work as a creative?

My work as a creative is based on developing my emotions and experiences as much as possible, without limiting myself, without fear of making mistakes, without fear of being judged.

All my creativity flows from my emotions, regardless of anything I see or hear. From a simple cry or anger to the thought that one day I will die and not wanting to be left wanting to live. The experience fills me with everything possible that I didn't have before taking these photographs. It marked a turning point in my life, because of the simplicity and unpredictability of this project. Thanks to this, I am not limited to doing or thinking what previously limited me.

Where are you based?

México

What is your vision?

Create and push myself with all or nothing, one of the most significant and important experiences of my life, I don't want fashion, I'm not interested in clothes, I'm not interested in luxury, it's just a garment, it's just a catwalk, if the opportunity presents itself, go for it, if not, I don't care, money comes and goes, I don't care, life is only one and I'm going to express my deepest feelings and experiences and it's not necessary to explain them, I want them to speak for themselves, to be felt, it's my first serious job and I'm going to improve, I want to show the unseen people, the judged ones, I want to show our rejection and hatred, I don't care about being a fashion stylist or a photographer or having millions, I just want to show my interior as much as I can.