Body Language: Donna Huanca

I’ve always found the two topics to be inextricably linked, and it was great to find an artist who seemingly understood that the personal is always political, and that the trappings that we choose to wear position us in society as a rebel, an academic, a punk, a team player, and on and on. I’ve watched her career grow from those early days into what it is today, a fully-fledged practice with works branching from a pervading central subject—the body politic.

Dress by Dries Van Noten, boots by Balenciaga, earrings by Maison Margiela.

ERIC SHINER — Your work, for me, has always been incredibly loaded thanks to your multidisciplinary exploration of the body politic, art history, fashion and fascism, and paint and performance. Might you let our readers know what fuels your art making?

DONNA HUANCA — I see my art making process as a form of meditation that creates a new language. It’s necessary for me to communicate in this way, using my intuition and subconscious to process the exterior world.

ES — Materiality is deeply important to your practice, and you have had success working across a variety of media in producing your work. At the core, with which medium do you feel the most at home?

DH — I would have to say sound is the medium that continues to seduce for me, perhaps because it is the most challenging, abstract, and requires the most silence.

ES — How has your time in Berlin influenced your practice? You decided to make it your home, and I’d love to know what about that city provokes and inspires you the most.

DH — I was nomadic for several years—the consequence of growing up in an immigrant family means you never feel at home anywhere. I grew up in South Side Chicago, spent summers in Bolivia, went to college in Houston, and continued in my studies in Frankfurt. As my practice took shape, I went on to work in Mexico City, New York City, Argentina, et cetera. When I first arrived in Berlin, I immediately felt at ease. I’m not sure how to explain it. Perhaps it’s because Berlin is the most unpretentious city I’ve ever been in, where people are in a constant state of flux, discovery, and experimentation. Those were the initial hooks that allowed me to stay and continue experimenting.

Left - Jacket, dress and leggings by MSMG, shoes by Marques'Almeida.

Right - Dress by Sonia Rykiel.

ES — If given the opportunity, what is your dream project? Where might it be and what might you hope to achieve with it?

DH — I would like to create a completely new atmosphere in communication with other beings and forces that are beyond our comprehension.

ES — Do you consider yourself to be political?

DH — Absolutely. We are all bound to our bodies as human beings, which makes it the most fundamental political unit. The personal is political.

ES — In recent years, meditation has become an important part of your life. I did the same when living in Japan. Tell us more about your practice and why it’s important to you.

DH—My performance work is essentially a live meditation, so it is essential that I seek inspiration from that same source. I have been practicing Vipassana (10-day silent meditations) for a few years now, and these experiences have changed my life. Meditation is part of a bigger constellation of research into my subconscious and genetic memory, where I source inspiration.

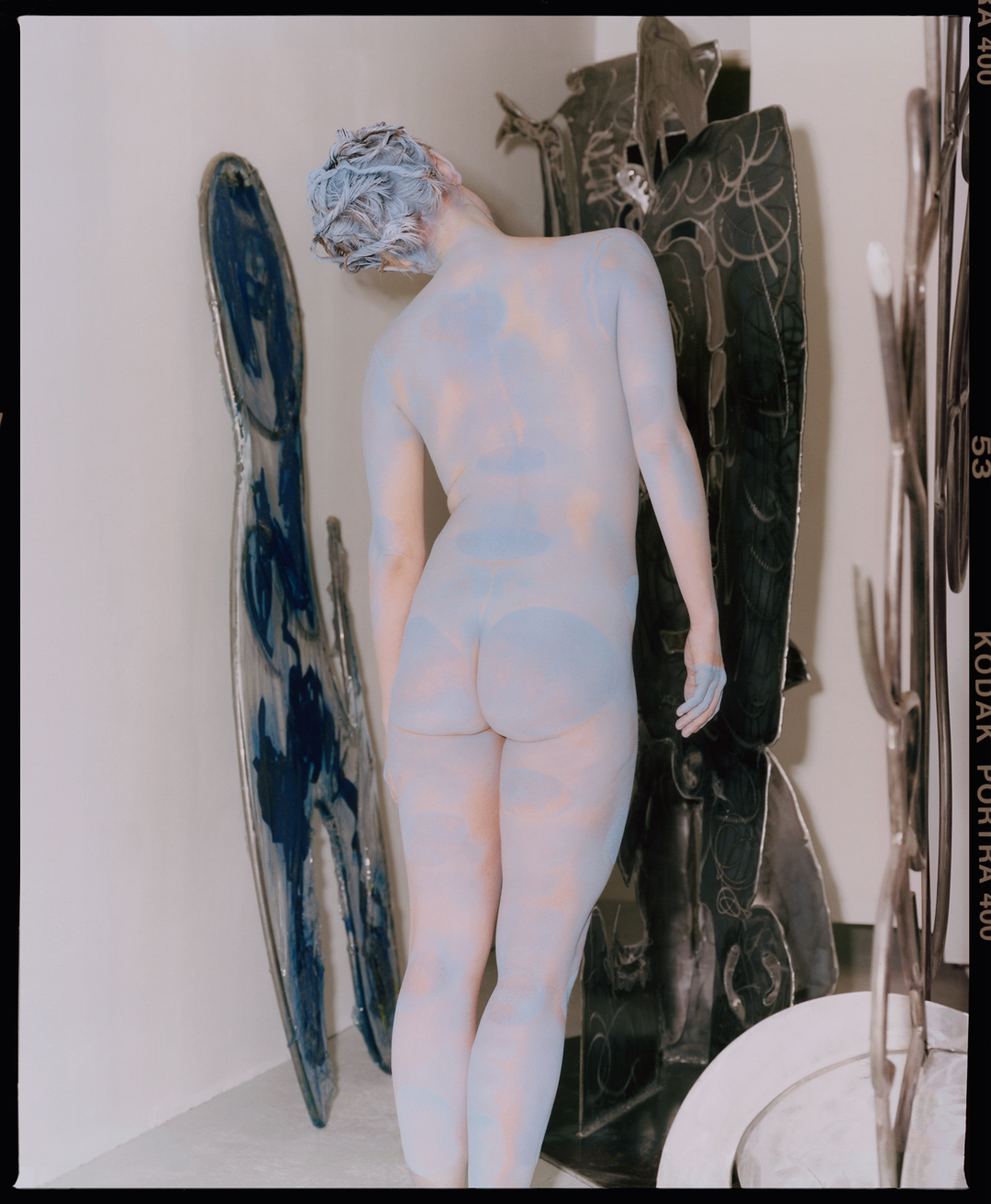

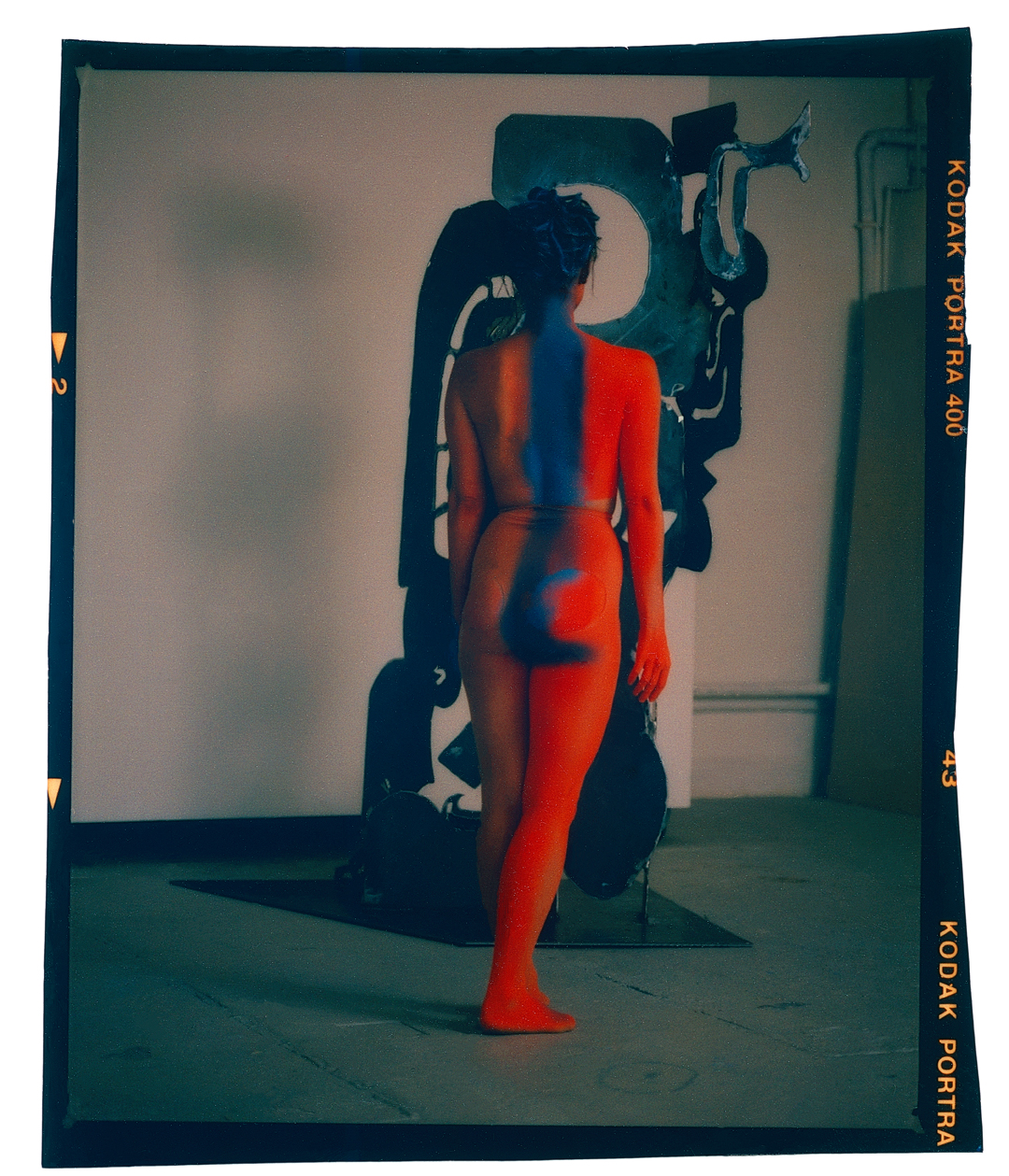

ES — How does ritual play a role in your practice? Your performance-based work at Art Basel Unlimited last year, for me, conflated dance, ceremony, and body art into a deeply moving action bordering on the religious. I’d love to know more about the background of that piece.

DH — BLISS (REALITY CHECK), 2017 was a breakthrough moment for me, because of its duration—eight hours a day, seven days straight. It was a huge risk, as the models were the primary focus and, as always, I had given them very little instruction besides, “Stand still, and when you move, please move slowly.” I never like to tell the models what to do as it is their own experience. I believe the element of chaos and improvisation is what makes the performances authentic. We had already been working together for years so there was an inherent trust and understanding between the models and myself. The work in itself is visually dramatic so I want the models’ actions to be as non-dramatic as possible.

The space the audience encountered consisted of very few elements: a scent, a white sand-covered stage, a soundtrack (that was mostly bass sounds to give them a vibrational pulse that also moves the sand, that keeps time, and keeps time for them), two life-size sculptures that had hidden speakers—I did not know what they represented at the time, but later I realized the one represented my father (male/fragility) and one was representing my mother (bountiful giving) and finally the two painted models.

We created our own ecosystem within those walls, which included backstage where the models would be painted, take breaks, eat their meals, and go to the bathroom. The models and I would wake up at 6 am, and I would paint them for three hours to prepare them for an eight-hour shift. During the day I would be backstage cleaning up and preparing their meals. I would often watch the performance in the crowd amongst the general public. I did not realize how intense the performance happening within the crowd would be. So this also added to my learning experience. The body paintings were improvised, so progressively got crazier as the week went on given that I had to create fourteen new paintings in seven days. Afterwards we would have dinner together and talk about the day, sleep, and do it all over again. We learned so much about ourselves, and it was very emotional for everyone involved, not to mention the audience.

Earrings by Maison Margiela.

ES — Fashion has seemingly had a constant presence in your work, from early show paintings to costume and other bodily adornments in your performance-based work. Why is that important to you? Do you approach it from a position of critique or adulation?

DH — My relationship to fashion has always been conflicted. I am both inspired and repelled by it. I don’t identify with the disposable and violently sped up aspect of trend-based fashion, but instead view it as a means to explore identity and self-expression that slowly evolves with time. Self-decoration has always been the primal form of communication and coding—this is the aspect I am interested in.

ES — What are your thoughts on Andy Warhol?

DH — When I think of Andy Warhol, I think of mortality. When that NYT article came out describing his autopsy, revealing his body was completely disintegrated from years of abuse, it confirmed that no one escapes mortality, not even the magician himself.

ES — Who are three young artists to whom we should be paying attention?

DH — The artists I’m most excited about are Vi Payaboon, Manuel Salano, Elysia Crampton, and Yves Tumor.

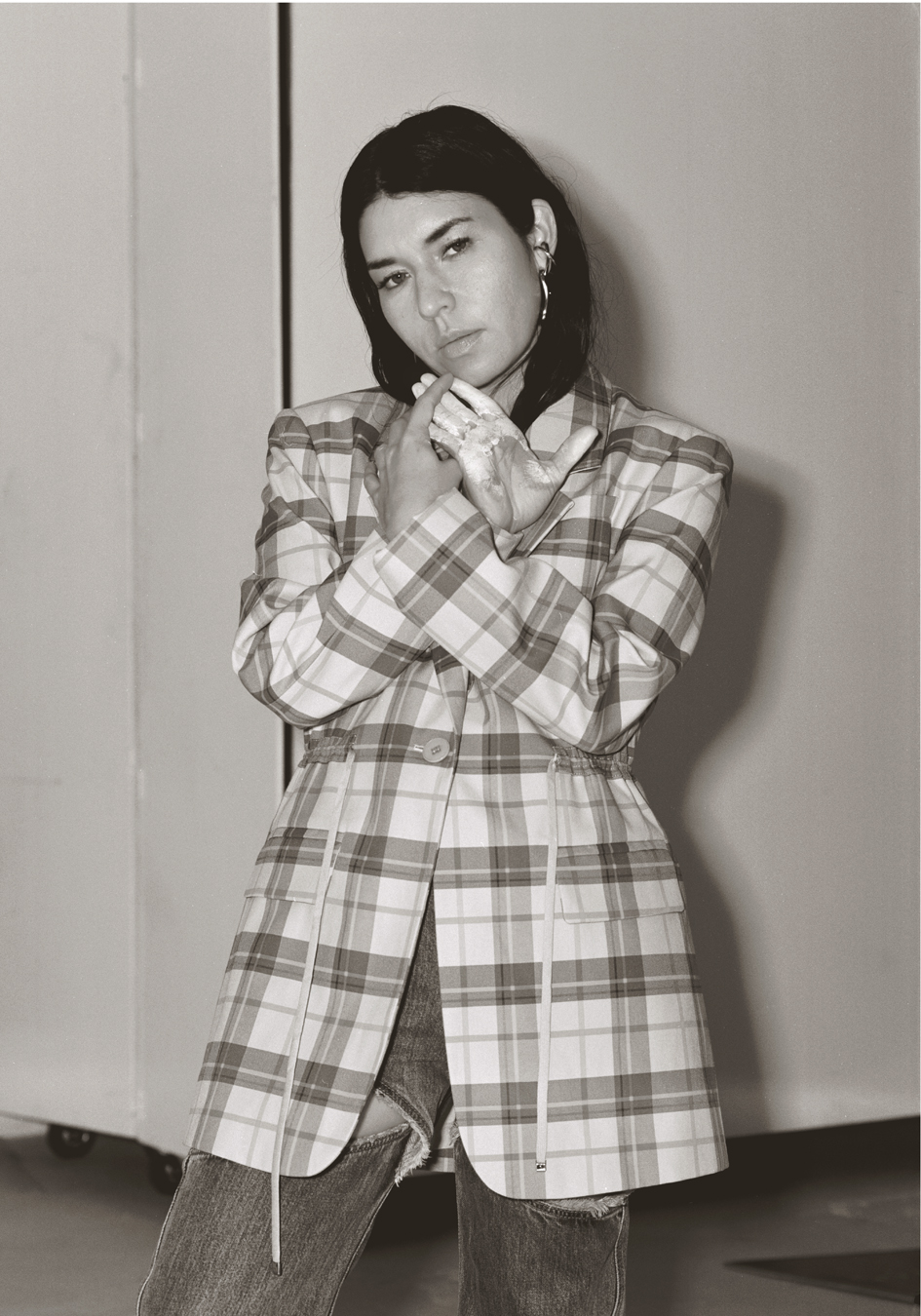

Left - Jacket by Tibi, jeans by Telfar.

Right - Jacket and shorts by Saint Laurent by Anthony Vaccarello.