The Bodybuilder

Tell me about your work.

I’m a sculptor, I studied in England, I’m from Brazil, and I think a lot of what informs my work is the desire to engage the use of the body occupying space and how that manifests itself in many ways, formally, politically, and also, it becomes a pivot from which to engage in loftier ideas about being and gender. So, I’ve kind of been approaching everything from that angle. My work usually involves my body in some way or another, and often plays with themes of the inside and the outside, whether I’m present as an absence that you can visually fill with your presence in the work, or whether I’m present as a volume that occupies space.

And what about this show?

This show started off with the desire to do something that was perhaps different from things I’ve done in the past, in the sense that it was directly addressing more contemporary events. So, the first piece you see when you walk in, "A thousand year kind of flood," is a group of gesticulations that are performed by me into a very big clay box—this is a thing I’ve been doing for a while, which is I fill a volume with clay so it becomes almost like a solid space, and then I move into it and create a negative with that process. So, it’s almost like, if there’s a mold-making process, you have a positive and then you create a negative, then from that you can create another positive. The positive in that event is an action, so it’s the activity of moving through and in this case, gesticulating my hands into a volume that produces the negative, and so the gesticulations are all from the news, watching online news, things that people share on social media, often, like news clips showing the disaster of Hurricane Harvey, or Hurricane Irma, or Maria last year—they’re all from that hurricane season. I was very interested in how people’s hands moved when they’re trying to do something that language can’t do very well, which is convey this large-scale disaster or crisis. So, hands gesticulating to show how a roof was ripped off the building and thrown across the street, hands that gesticulate how the living room used to be here but isn’t anymore, or how high the water went—the ways in which the body becomes engaged in doing more than what language can.

Then with the hands with cast fish, and the pieces that follow into the interior gallery, they’re all dealing with moments of loss, in a way, the loss of the body. These works are based on funerary urns that are from the Amazon region, Brazil and other countries from a time when those countries didn’t exist. Then in the back we have "SHEE," which is a habitat devised by a space architect that I met—she’s the coolest person I know, and she got this European Space Agency commission and made this habitat and it’s in its undeployed—let’s call it its storage or sleeping mode in the gallery—and I’ve been crawling and interacting with it in a very tactile way, and slowly destroying it. So, there’s a lot of loss, destruction themes going on, which for me tie into the moment we’re at, perhaps differently and more directly than other shows I’ve done in the past.

I love the weird connection between a funerary urn and outer space. Can you talk about that a little bit?

What interested me with these urns is that they’re kind of machines—the way that they are made and the belief system that structures them into being is very much this idea that the ceramic urn is there to control and contain and direct a process, so in a way it has a function. It’s an object that has an agency, like how a machine or a mechanical thing does. They’re very different from how we use funerary urns, like when we put someone’s ashes in it, and it’s considered a resting place for these ashes and just a place of memory, but the urns in these Amarindian cultures that were producing these were very much devised to control a very powerful force, which is your spirit. In these belief systems, when the spirit left the human body it was no longer human—you don’t have a human spirit like you do in Judeo-Christian religions where when you leave your body as a spirit, you still look just like you but you’re see-through now, right? In these cultures, it’s very dangerous and you could potentially become many things—a jaguar, a snake, a bird, or you could become a spirit that is used by a rival shaman in a rival nation.

This very dangerous transition from losing the body is what these forms mediate for these cultures. So, I became very interested in these urns in that capacity, because it’s an object that’s designed to mediate the loss of humanity in a way, the loss of a body, and if you’re humanity is your body, when you lose your body, you lose your humanity. Some of them were shaped like human beings, literally they’re just people with arms, legs, torso and a head out of ceramic, and the body of the dead would go inside. So, it’s like you’re putting yourself into a new body. Others were shaped in different ways where it suggested transformation into an animal. Probably the most popular ones, which are the majuata urns, which were very tall, like three feet—they were huge, and you would put a whole body in it. They suggest a transformation into an owl or some kind of bird; others suggest a transition into things that could be a snake, or a jaguar, other animals, turtles. So, in some, you have these urns that are trying to retain the human, as if it’s going to hold your spirit and its association with our culture and your descendants, so we can continue to use you as a source of identification and power. Then others were encouraging you to go be a bird, because that’s good—don’t be a jaguar and come back and eat your children. Just go be a bird.

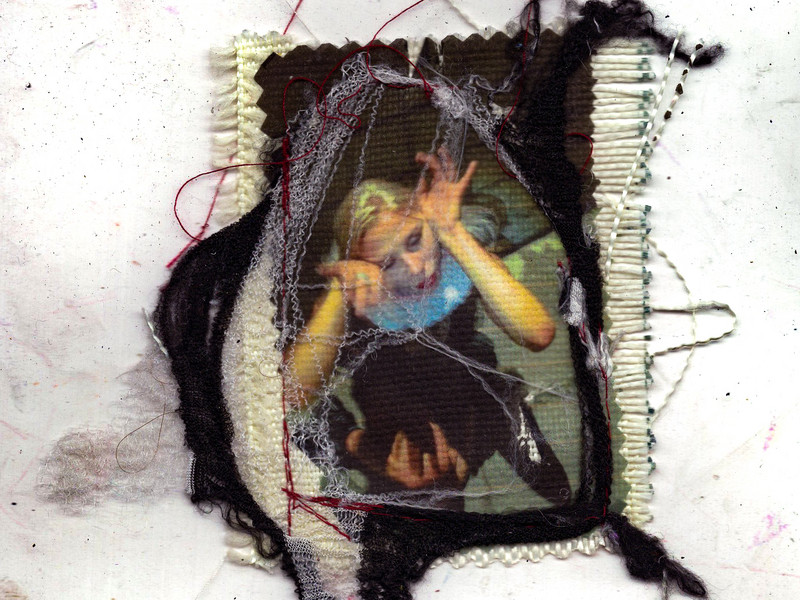

Above: '...a thousand year kind of flood//completely ripped off//whipped up and smashed//the living room//relationships that didn’t withstand//an additional 15 to 25 inches of rain...' and 'Urn 2,' 2018.

Do you feel like any of your sculptures are turning into an animal of some kind?

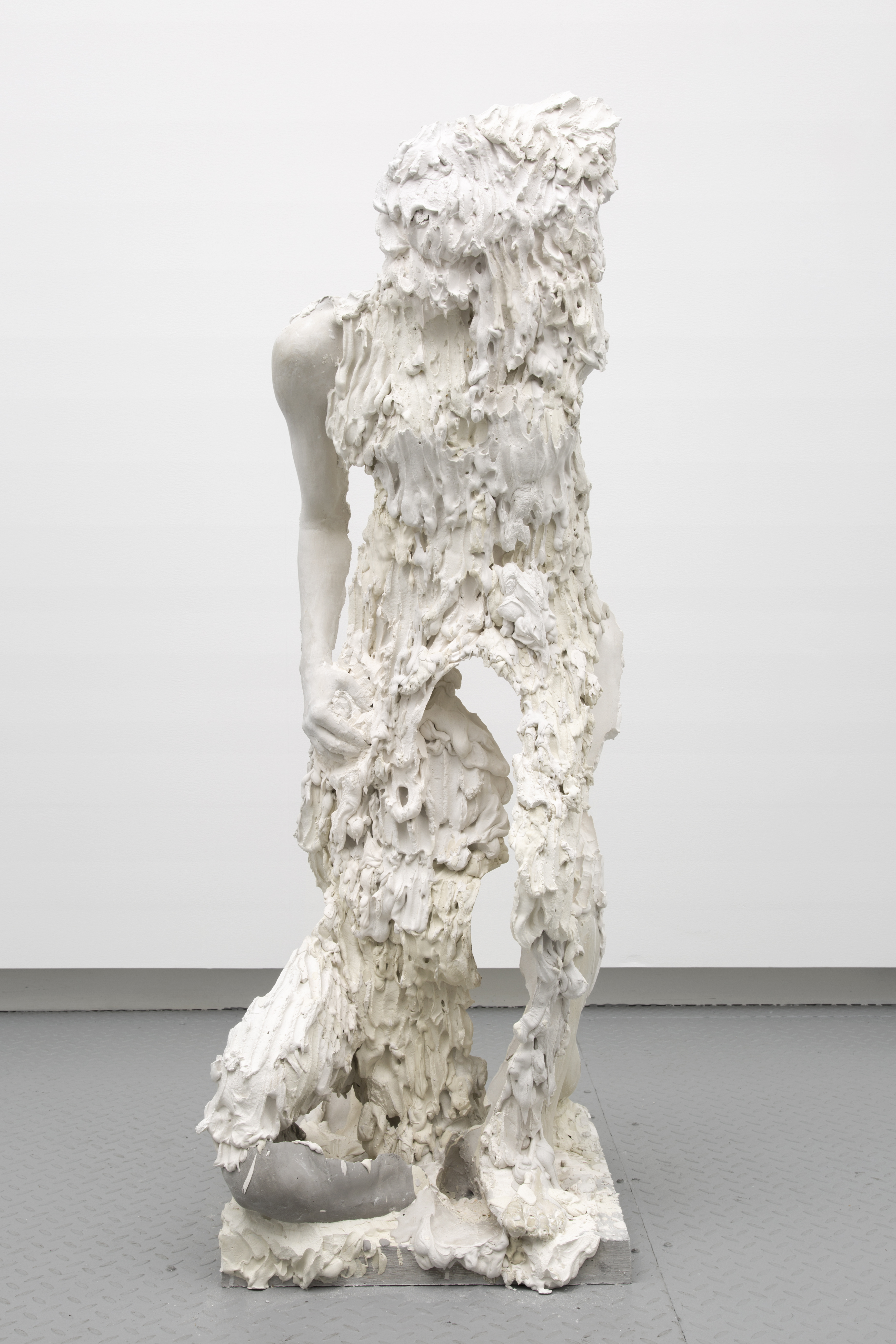

I was thinking along those lines with some of them. Maybe not literally, so there isn’t a piece of a bird or something like that, but with the central piece, "Urn 5," first I built a ceramic urn—they’re all terra cotta coil pots, that’s how I built them, because that’s how they were built, actually—so I built a pretty large one and I got inside, and then sort of I twisted myself so I kind of smashed myself out of the urn, and as I was doing it, I was casting my body so that my legs would become almost like these filets of plaster and also kind of breaking the urn itself so it kind of collapsed. I see it as a weird fusion of something that looks quite nest-like, but also bird-like in the repetition of the leg.

It’s kind of like you’re the spirit breaking out of the urn.

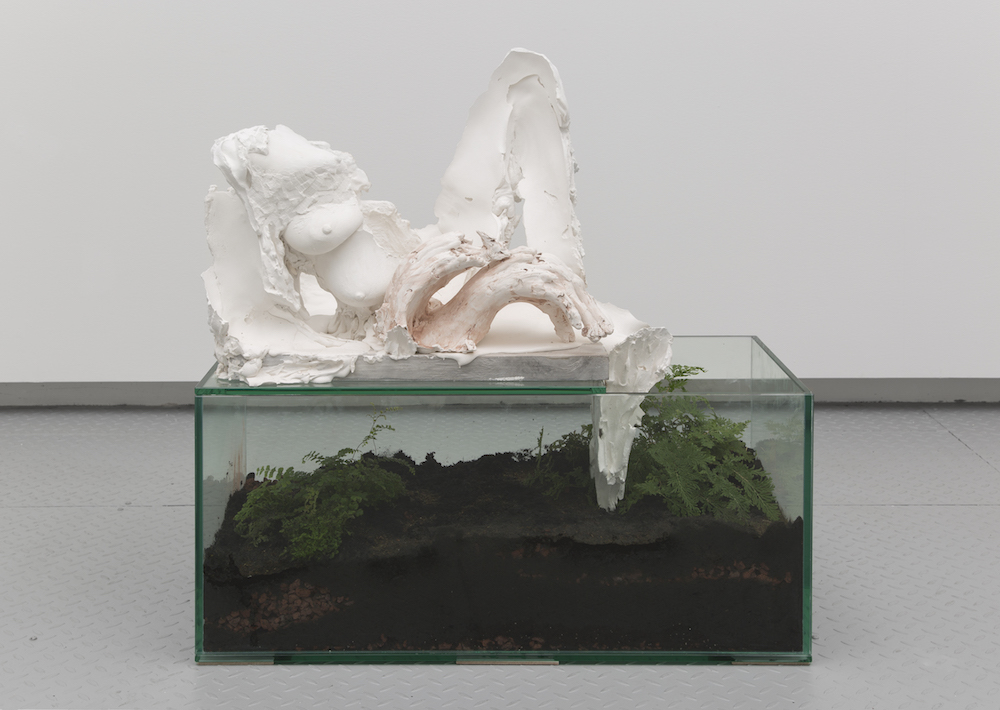

Yeah, and suggesting a sort of feathered structure, or the wing of a bird. And then this other one, the position I’m assuming is very much recognizable as a dog or a large quadruped animal that’s sitting. With the one with the glass piece, there’s the hands that are almost diving. And the many breasts, I’m thinking of them as sort of things related to amphibians, like fish or frogs, this idea of many eggs, and the leaping or jumping. The repetition of the hand I hope suggests a bit of that action. But I try to keep it very loose, these associations—I find that the piece collapses into very much like a body turning into a jaguar—it loses its ability to stay in this weird hinge where it’s really showing transformation instead of an a to b.

So, what about the piece in the back?

So, this is a scale replica of an object that’s called "SHEE," which is an acronym and it stands for Self-Deploying Habitat for Extreme Environments. It was a European Space Agency commission that asked for proposals from different consortiums and different groups for a habitat that could collapse in on itself and become smaller, then be shipped somewhere like, for instance, Fukushima, where there was a nuclear disaster and human beings shouldn’t really be exposing their bodies to the external landscape. Or if there’s a huge earthquake or nuclear disaster where you could put this device as a habitat—or, of course, it could potentially go in space, so like the moon or Mars or wherever you’re thinking of having actual colonial enterprises. So, it’s a device for recalling spaces human beings have lost, in a way, or never had.

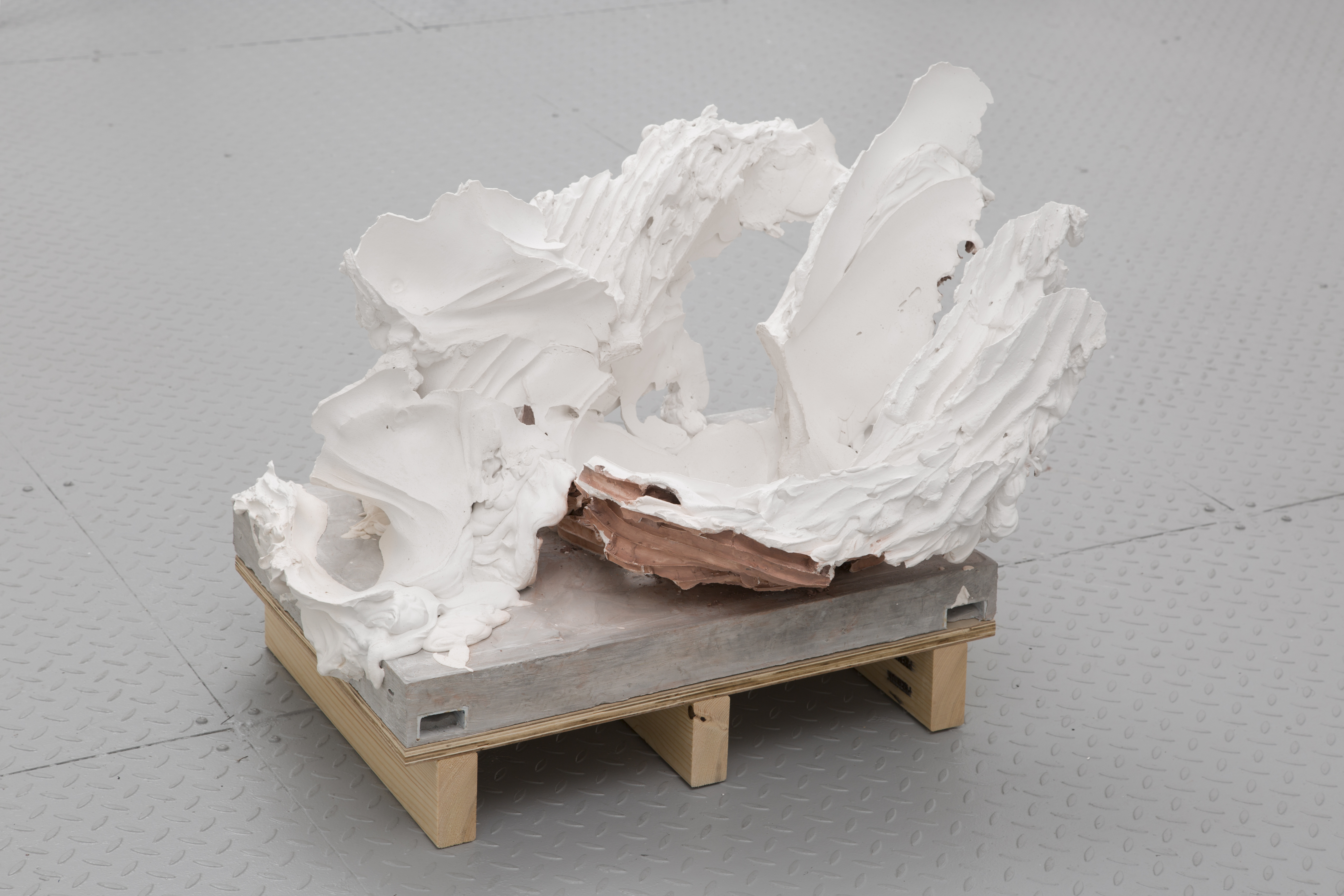

So, it contracts into this small shipping container structure, and then it expands. Barbara Imhof, the designer, uses the word ‘petals’ to describe these curved walls that open out. There’s an engine and they rotate, they self-deploy, out to make a semi-circular space here and then, a much larger semi-circular space on the other side with these walls. So, they all expand outwards, which turns this into a 300-square-foot living and working space that is completely sealed off from its exterior environment—in it’s real form. I did this replica out of cardboard and wood as a mold, so this is essentially a structure I’m using to create a sculpture, and the sculpture is basically me moving through these spaces, which are quite tight, and not designed to be occupied in this form, this is how the thing ships, if you’re in here in its undeployed form, something has gone wrong. So, I’m occupying it from one end to another, and using plaster to leave a trail of my actions, and what I’m doing is essentially just coming into physical contact with the surfaces of the space—leaning into a corner, resting my hand on a shelf, sitting on a table, reclining against a curved wall, and just moving through the space and occupying it in that way where I’m leaving a trace. As I’m doing that, I’m taking the whole space apart, so I’m destroying it, and that removes the surfaces that were supporting my body, so the corner I leaned into is gone, the table that I rested on is gone, the shelf is gone, the only thing that’s left is the negative space that was impressed between my body and the shelf.

There’s this really beautiful Japanese concept of the moonlight coming through a window leaving this rectangle of light in the space and it suggests that that the space between things is physical and animated in some way, so it’s tangible. So, I’m making the space between the object and myself tangible by leaving these forms, and I’m interested in how that form isn’t a replica of my body and it’s not a replica of the space, it’s a replica of the interaction—and how the space then only remains in this way if I touched it. It’s a visual sculpture in the sense that you look at it, but it’s completely defined by touch, because that’s the only memory of the space you’re left with are the places I actually touched.

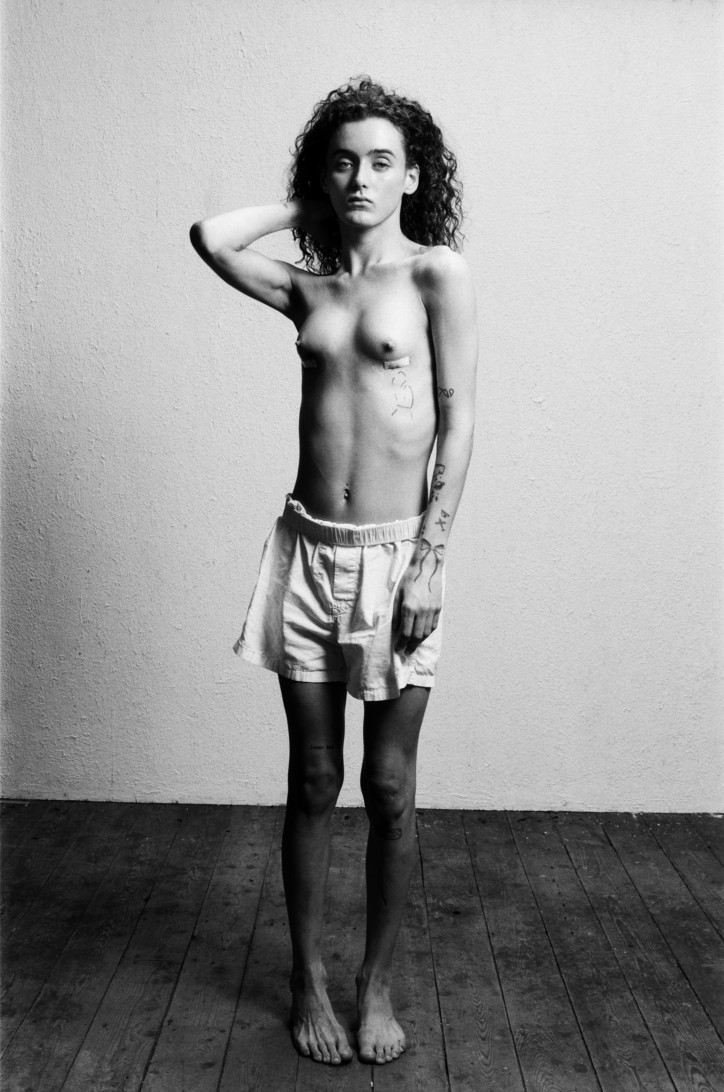

Above: "Urn 1," 2018 and "Urn 3," 2018.

Would you ever go to space?

I’d rather not! I think there’s enough going on here. There was recently a survey in Canada where it asked if you would want to go to Mars if there was a possibility, and it was interesting how gendered the response was, something like 70% of men said yes and only 20% of women said yes. I think there’s something there that says how people think about the earth, and adventure, and colonial enterprises, and gender stereotypes. There’s a gender stereotype for all these male heroes. I think all the mechanics of, for example, Trump’s idea of building a colony on the moon, and all these ideas of going to Mars—I find all this really problematic. I think there’s an escapist fantasy in it. I went to see "SHEE," it’s actually a thing that exists, which is in the International Space University, which is a thing, which is in Strasborg, France, so I’ve photographed it and tried to move through it when it was closed to get a sense of whether the sculpture would work. It was really interesting talking to the scientists there who built it, and they told me there’s this really problematic dust on Mars, so that if you took this to Mars, the likelihood is that the dust would just eat all the seals and you’d just have everyone die of silicosis really quickly. I think there’s a lot of components of how the environment is in these spaces that I think are being taken for granted in a lot of the ideas of how easy it would be to just make an atmosphere on Mars, Earth is doomed, whatever. So, I was sort of thinking of doing a piece that engaged with that.

It’s interesting how you use materials that are earthy but also things that are more technological.

I’m working on a project now that involves some 3-D printing. Because in a way, like with the gesticulation piece, it’s kind of an analogue 3-D print, creating a solid space that you then carve out a hole into with your hands—and then I cast it in layers, so there’s different colors. It’s kind of a reverse cave woman 3-D printing.

And then it’s a plastic, correct?

It’s actually an aqua resin, so it’s not toxic. I try not to use anything that’s toxic—I find that it contradicts the work.

Is plastic toxic?

A resin is, yes. Like for 3-D printing, you have a bunch of different options, one of them is PLA which is a corn-based resin, and that’s not toxic. I’m not going to make an artwork about the environment that uses a super-toxic resin.

And you come here and work on the "SHEE" project everyday?

Yes, the show is until November 4, but it’ll be ready next week.

All that remains is the plaster—will that be destroyed, as well?

I think so.

Is it going to be a party?

A destruction party! It’s always kind of sad for me to destroy my work, so probably not. I’ll probably do it slowly with a Sawzall.

It wouldn’t actually be able to be removed from the gallery?

It could be, but it would be so large. If it went somewhere, it would be this major institutional acquisition, maybe—I don’t know if I’m there yet. I’ll be emotionally ready to destroy it. I’m also debating whether I should leave some of the structure itself, though, because a lot of people have gone into the sculpture. If I undo it all, it’ll just be the residue.

I like the idea of removing it all.

Yeah, because then it’ll just be the memory of it.

'Until Different' is open now until November 4 at Arsenal Contemporary.

Photos courtesy of the gallery.