Part of an emerging movement in France — a new existentialism that turns its gaze on all of existence rather than on the human perspective — Schultz was a close collaborator of the late French philosopher and anthropologist Bruno Latour, who championed this ‘nonhuman’ idea. Their co-authored work, On the Emergence of an Ecological Class: A Memo (Polity Books, 2023), translated into 12 languages, provides a blueprint for constructing a political subject poised to advocate for the planet’s habitability. Praised by scholars like Dipesh Chakrabarty, Clive Hamilton, and Slavoj Zizek, Nikolaj’s recent book Land Sickness is a hybrid text that revisits the human figure and engages with the sociological and existential questions that the Anthropocene forces us to pose.

Newspapers have crowned him “the coming star of sociology,” and similar to Latour, his influence extends beyond academia, permeating the art world and inspiring artists and curators such as Fontaines D.C, George Rouy and Hans Ulrich Obrist. Before his passing, Latour introduced Nikolaj to Hans, but it was last summer, prompted by Corinne Flick, that Hans delved deeper into his work, picking up Land Sickness as his summer read.

Hans has played a unifying role in the art world, cultivating spaces where people, perspectives, and ideas intertwine. As the artistic director of the Serpentine Galleries, he has curated numerous exhibitions and projects that engage with environmental issues and sustainability. Additionally, he has promoted eco-conscious practices within the art world itself, leaving a lasting impact on the way contemporary art addresses ecological challenges. In October, he invited Schultz to give a talk at Serpentine’s prelude to this year’s Infinite Ecologies Marathon, which explores this new perspective on our relationship with nature, redirecting our attention to the world as it is rather than the human-centric one we’ve constructed.

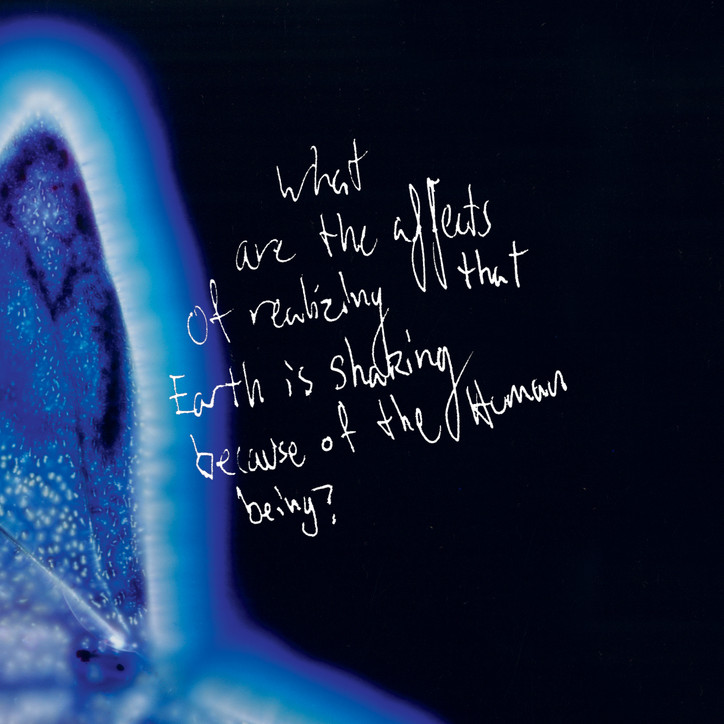

A few weeks after our initial meeting, I managed to arrange a call with Ulrich Obrist and Schultz — a feat in itself — to discuss Land Sickness, the Anthropocene, and this new Earth “shaking beneath our feet.” Nikolaj's hand-written quotes shared throughout this article are inspired by Ulrich Obrist's Remember to Dream! 100 Artists, 100 Notes, a collection of "thoughts for the day, dreams, drawings, musings, jokes, quotations, questions, answers, poems and puns" handwritten on Post-it notes (and other scraps).

HANS ULRICH OBRIST — In this age where information is abundant but memory often falls short, I think it’s important to acknowledge the artists who have contributed to the discourse on the climate emergency since the start of the movement. In my field, Gustav Metzger springs to mind, who has been at the forefront of this struggle since the 60s/70s really. Then there’s Agnes Denes, whose seminal 1969 manifesto resonates powerfully today. And the Harrisons who contributed a manifesto that criminalized plastic for our ongoing Back to Earth program at Serpentine. There are all these artists in my field, so I’m curious, Nikolaj — who do you see as the pioneers in your field?

NIKOLAJ SCHULTZ — As you know very well Hans, the discourse on our ecological problem stretches back to mid-century movements, like Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring in 1962 and the ‘Limits to Growth’ report in 1972. Yet, my field of social theory was relatively late in developing a conceptual language for discussing these changes — even if you can, of course, find ecological “undertones” in modern social theory. For example, in the work of one of my heroes Karl Polanyi who perceptively intertwined social relations with environmental conditions in his analysis of societies. There has been more progress in recent decades, thanks in part to thinkers like our common friend, Bruno Latour, whose seminal work reintegrated nonhuman actors into social theory. Also led by figures like Timothy Morton, Donna Haraway, Emanuele Coccia and Anna Tsing, among others, this shift in thought has illuminated the agency of wolves, spiders, octopuses. Latour in particular helped bridge these ideas into the art world, which you’ve also been instrumental in doing.

HUO — I think that to properly tackle the significant challenges of the 21st century, we need to overcome the fear of sharing knowledge, so throughout my work I’ve aimed to do just that by bringing people together. I see curation as I do it as a form of “junction-making,” as J. G. Ballard once described it to me. I’ve created events like Serpentine’s Marathon and exhibitions like Laboratorium, Cities on the Move, and do it to serve as vectors between people and ideas.

When I first met Bruno, he felt undervalued in France at the time, particularly by its institutions, so I invited him to collaborate, together with Barbara Vanderlinden, on what we named “Laboratorium”, which looked at the workspace of artists, the studio and the laboratory as a kind of network. He was hesitant at first, but his involvement turned into enthusiasm as he organized tabletop experiments together with Peter Galison, Caroline Jones, Panamarenko, Rem Koolhaas, and Isabelle Stengers — who made the private practice of experiments a public affair. And of course, the actor-network theory was kind of crucial for that.

It all grew out of us bringing people together. You of course worked even more with him and were really the person he was most interested in as part of this younger generation of sociol - ogists, so I’m eager to hear how that came to be and about this book you co-authored before releasing your own.

NS — I first crossed paths with Bruno when he was my teacher at Sciences Po in 2015, engaging with his course on the philosophy of nature, which later influenced his seminal book Facing Gaia. For some reason he found me a good student, so slowly, in the following years, we started exchanging ideas about this new Earth that had begun shaking beneath our feet. These exchanges turned into a real collaboration around the time he was writing Down to Earth, in which he introduced the term ‘geo-social classes’ that we would collaborate on until his death.

As a sociology student who — before I encountered Bruno’s thought — had been trained in the old German tradition of critical theory, and in Marxism to a certain degree, I thought that this idea of a new concept of class for a time of global climate change was interesting. And knowing that Bruno tended to sometimes not follow through entirely on his many conceptual inventions, I pressed the case that we should take this newly minted term seriously and develop it further than he had done initially.

This we did, then we began writing our book on the topic in 2021, analyzing why ecological parties struggle to gain political support despite the overwhelming evidence of the unfolding ecological disasters. Our book, on the one hand, sought to diagnose this void in political effects, the absence of mobilization and lack of political passions for ecology — and on the other hand, it tried to indicate pathways out of this political inertia.

We argue that ecologists haven’t taken the cultural struggle for ideas seriously enough, and art plays a significant role in this struggle, capable of shaping our sensitivity for issues previously ignored and driving social change. Bruno was heavily inspired by your work in this regard, an insight that followed him for many years, all the way up to his last book, On the Emergence of an Ecological Class, the one he and I wrote together.

HUO — That’s exciting. I read the book in German. You mention movements like Fridays For Future and local organizations working locally and nationally, drawing a parallel between historical workers’ movements and the present need for an ecological class today to halt climate change. Yet, you advocate for a politics that broadly protects our Lebensgrundlage — our foundations of life. It made me think about Joseph Beuys and a lecture he gave in Rorschach, back in the ‘80s when I was still a child, about his role in co-founding the Green Party. He was an artist aiming to marshall this ecological class you refer to. From your perspective, what are the practical steps we can take to move beyond the book and into societal action?