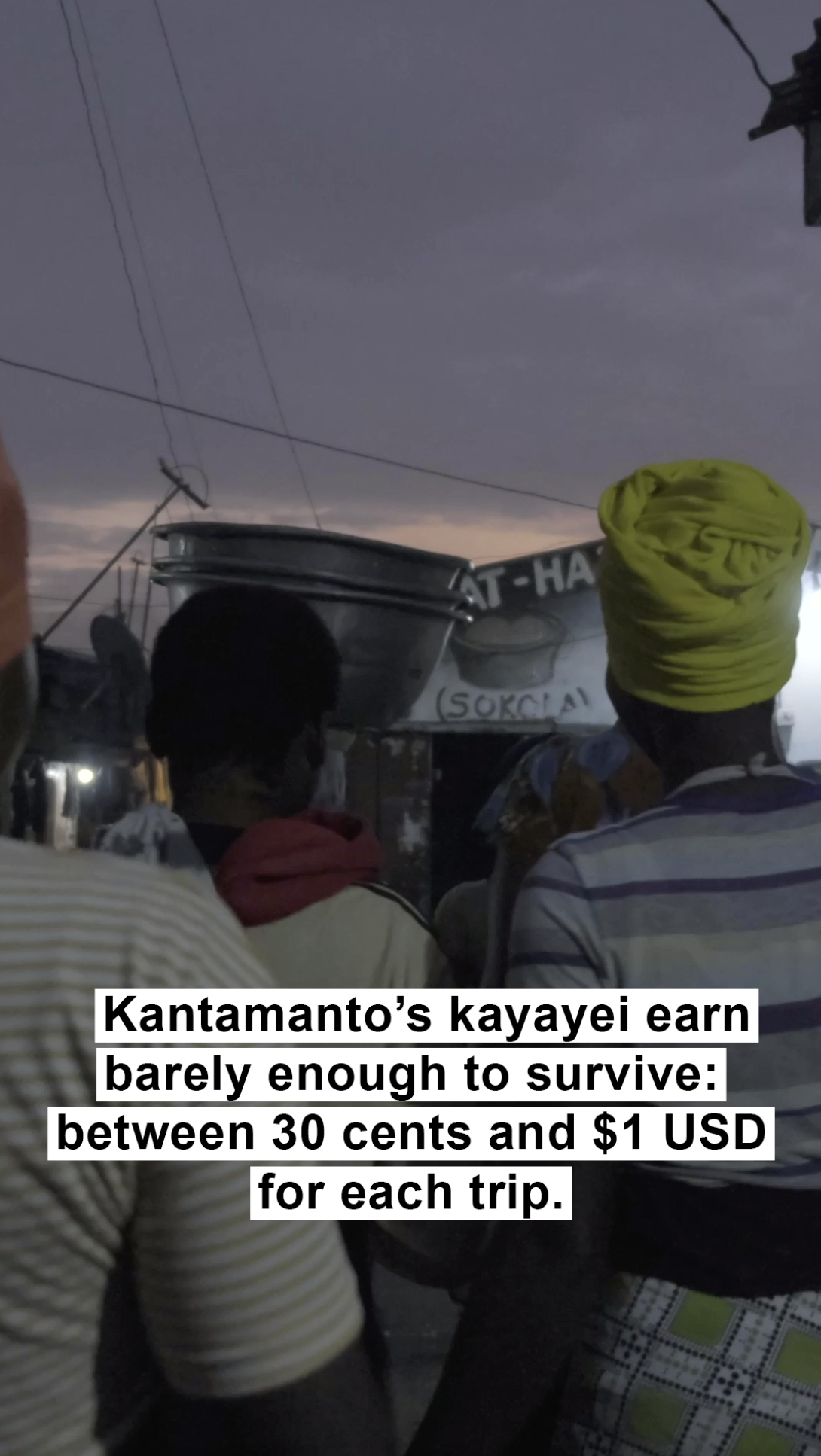

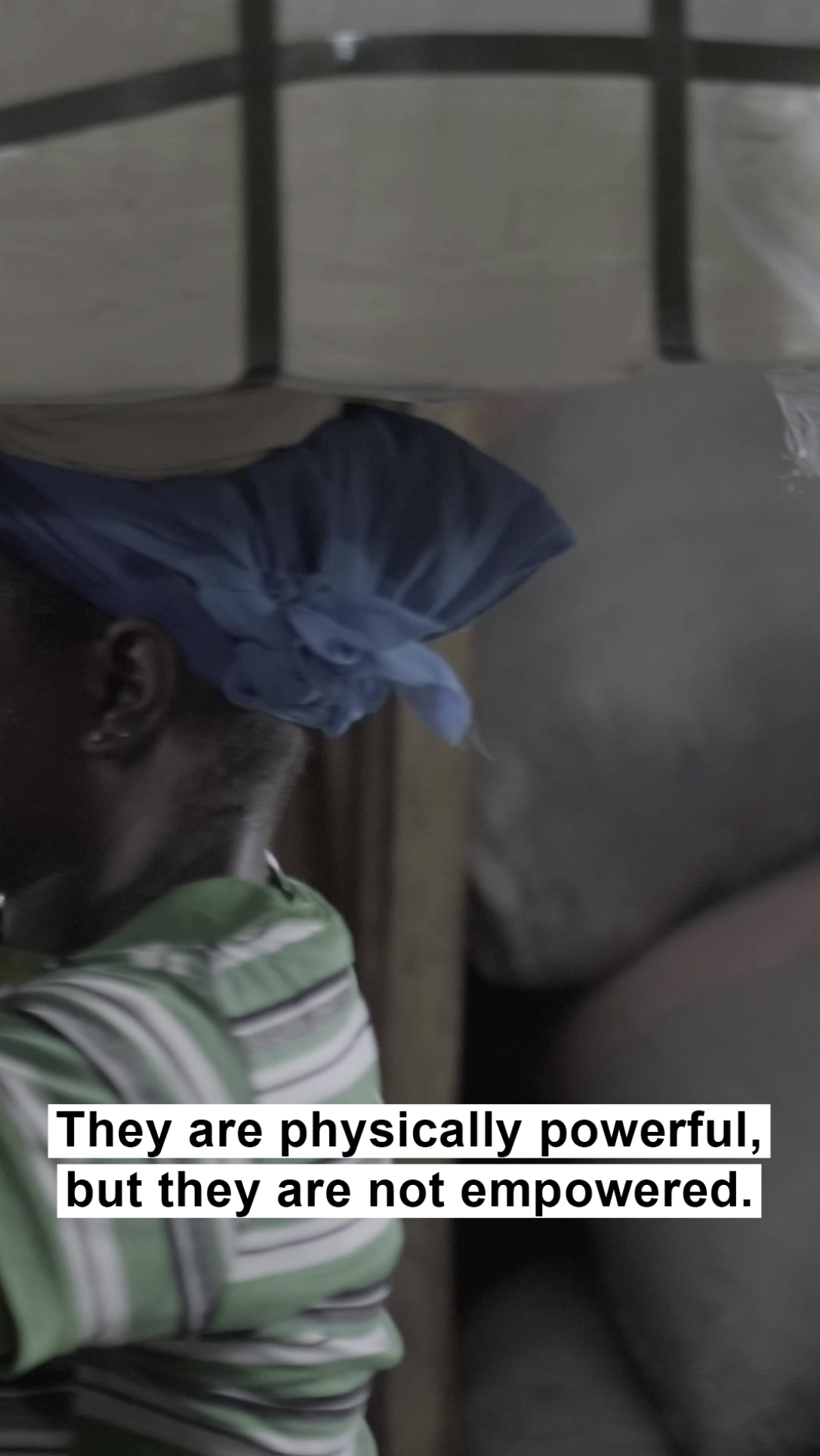

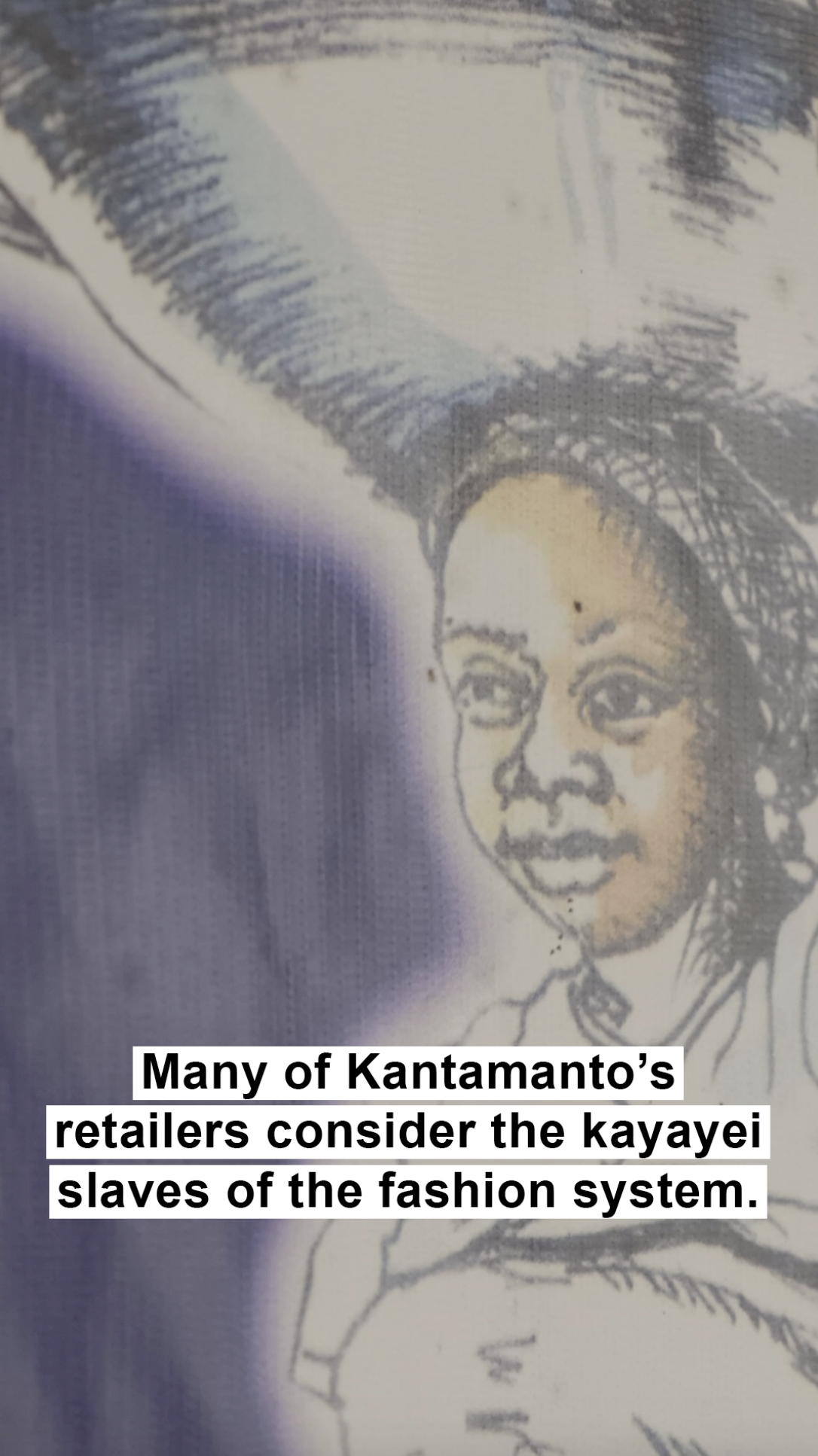

Buy A Bag, Feed She Who Carries The Burden

Below are stills from the film to give you a glance into the world of the women fed by an office bag purchase.

Stay informed on our latest news!

Below are stills from the film to give you a glance into the world of the women fed by an office bag purchase.

Hi Bruce. Congratulations on opening a major show! How do you feel?

It’s always nice to have a major show especially since the work is very strong and it looks great, but I have to say that I could have put many more photos in the show without a loss of quality.

You were intimately involved in the curation, what was the process of looking back at your career like?

I curated the show and chose photographs that I liked, some iconic and others less known, showing where I started and where I am now.

Before you were a photographer, you studied sociology. In a way, I view your photography as a sociological study. Would you agree?

I only took one sociology course in college. I photograph what interests me.

You mentioned watching Antonioni’s Blow-Up (1966) as a turning point that decided your pivot toward photography. Does cinema continue to have an impact on your photographic practice?

I’m not a fan of Antonioni as a director but because of the movie Blow-Up, photography became fashionable in 1966 so it crossed my mind that I could try being a professional photographer. I never held a camera in my hand before.

Cinema has always had an impact on my photography. My candid work has definitively been influenced by Film Noir among other genres.

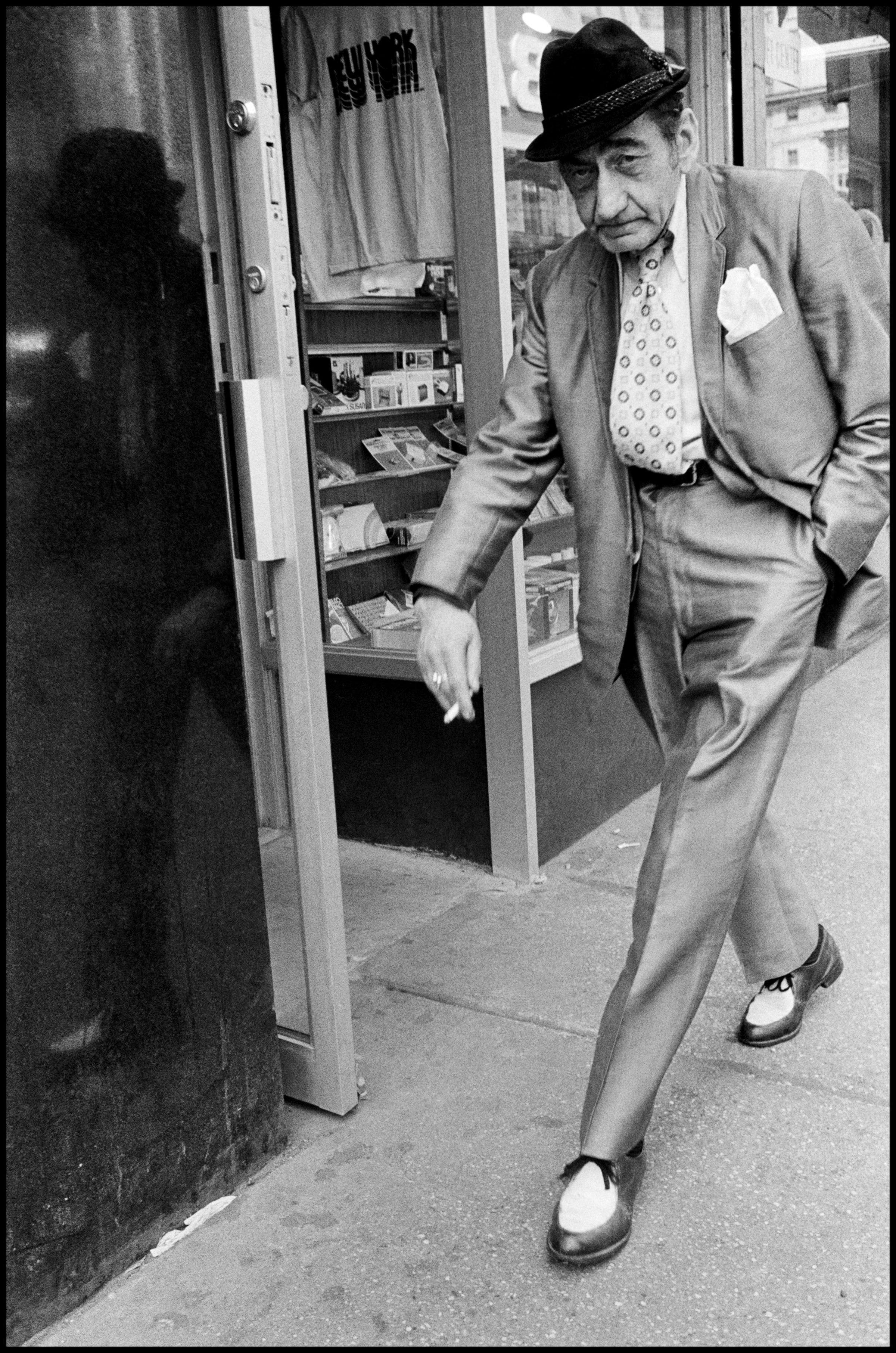

You started with black-and-white photography and people on the streets of New York which you intimately know, in a time when photography was transitioning toward color and increasingly given a political function. How and why did you decide against what was in vogue?

It was in Coney Island that I started my black-and-white photography, and then I worked on the streets of New York.

I see in B&W and I’m not into trends. My motto is “Be Yourself”.

Then you started doing color photography only recently. Why?

I still do B&W, but I felt I needed a change. You can’t do the same thing forever, and when you start something new and different, you feel energized.

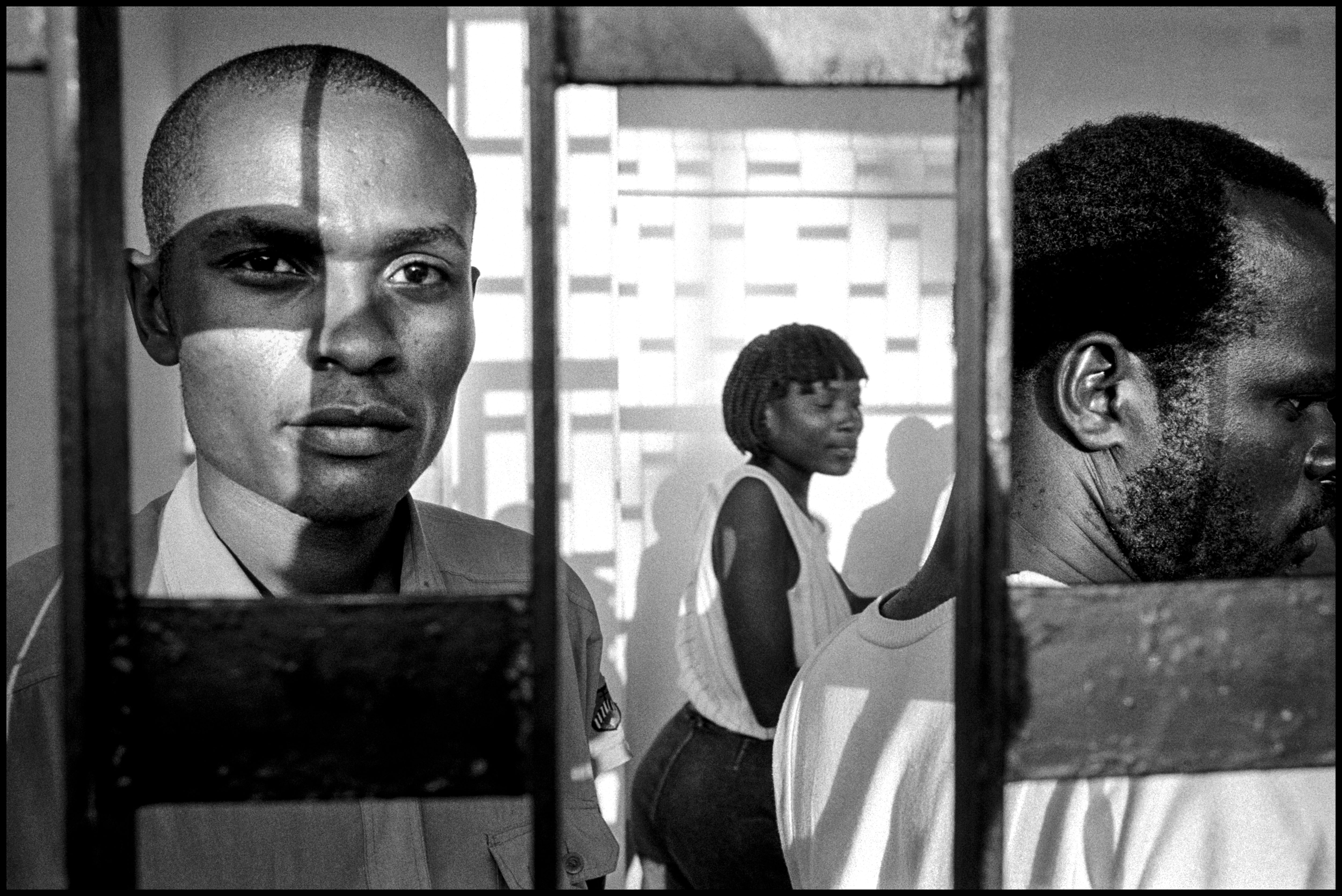

You use flash and capture people in their most vulnerable moments. There is a different kind of closeness here. What draws you to socially marginalized populations?

I don’t agree with your statement about “vulnerable moments”. What draws me to socially marginalized populations is that I’m an outlier and not part of the mainstream. I just feel comfortable with them.

Do you feel connected to them through photography?

No, I feel connected to them through life, and photography is the bridge that connects us.

Your photography evokes strong reactions from critics and the public alike. Do you ever feel misunderstood for the choice of your subject matter?

I have many people — critics and those in the public who consider me legendary, and others who don’t like my work. Whether you like it or not, it doesn’t leave you indifferent. My pictures are about real people and real life. I photograph what’s inside my heart.

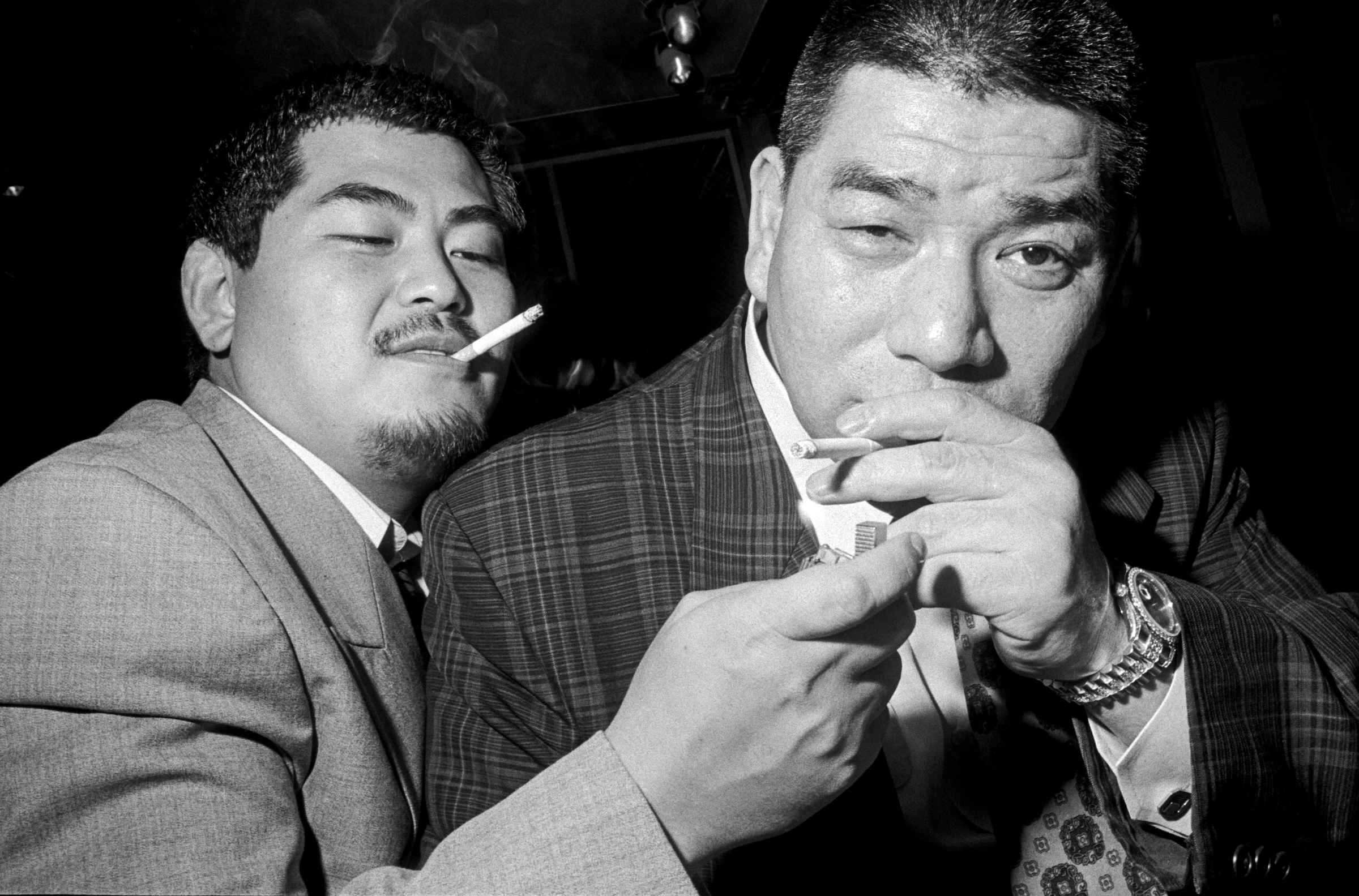

You’ve photographed Japanese yakuza mobsters, sex workers, and bike gangs. Could you say more about such attractions?

Since childhood, I have been attracted to characters, and If you know something about my past (myself, my parents), you’ll know where this attraction stems from.

Do you ever stage your subjects for theatrical effects? Or are you only interested in utmost authenticity?

In my newer face and waist-up portraits mostly in color, I ask permission. All my other work is candid as is some of the recent work (Bikers, Korea, Italy, etc).

Do you pay attention to other filmmakers and photographers? If so, who are you watching?

When I started photography, I learned my craft by looking at other photographers’ work and then eventually I became Bruce Gilden. These days I pay attention to what’s inside myself.

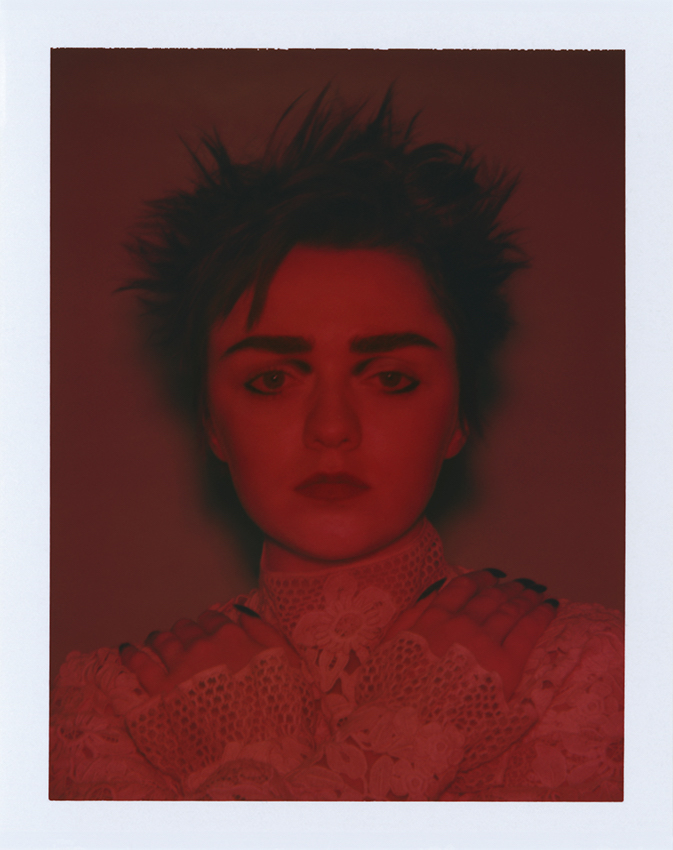

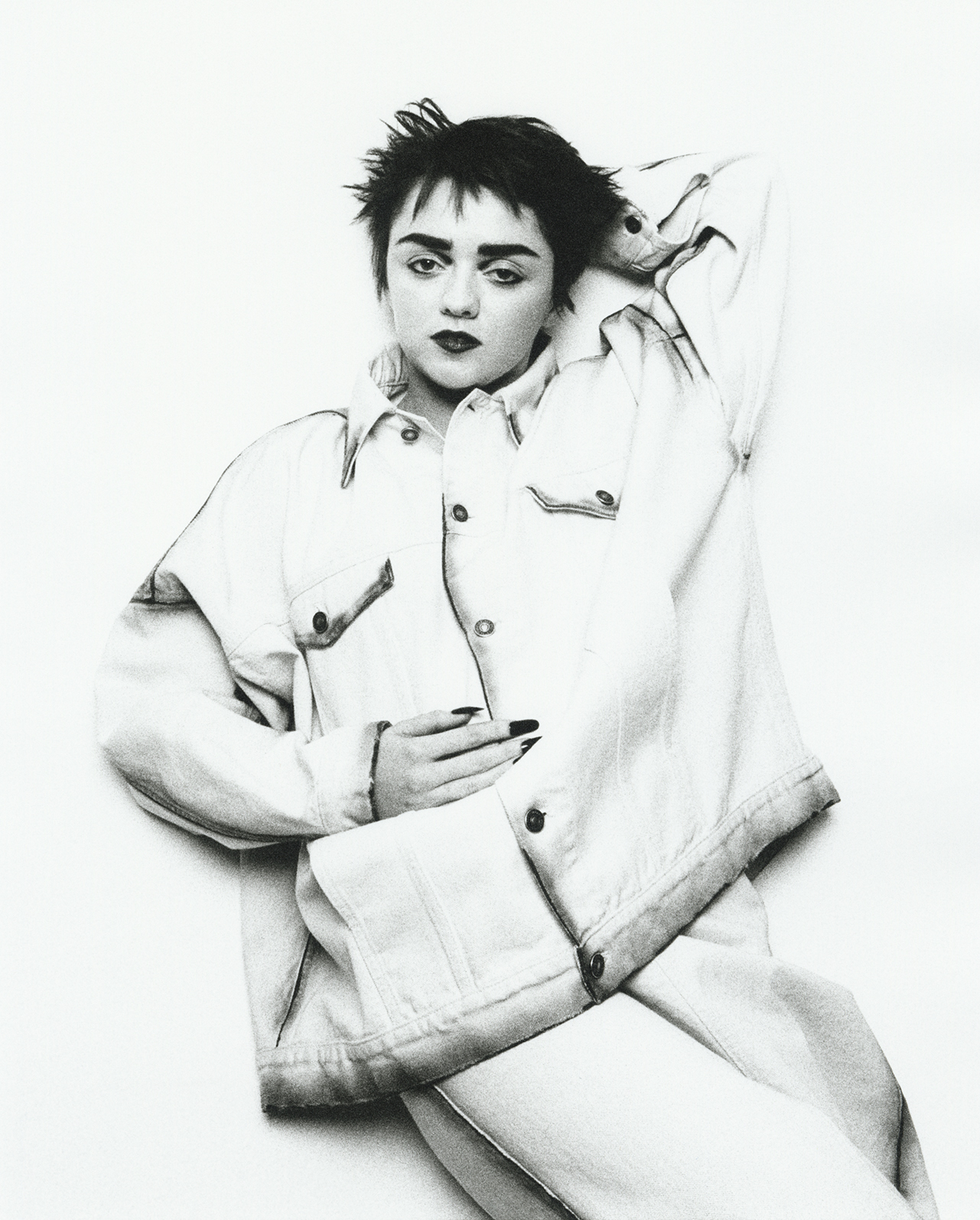

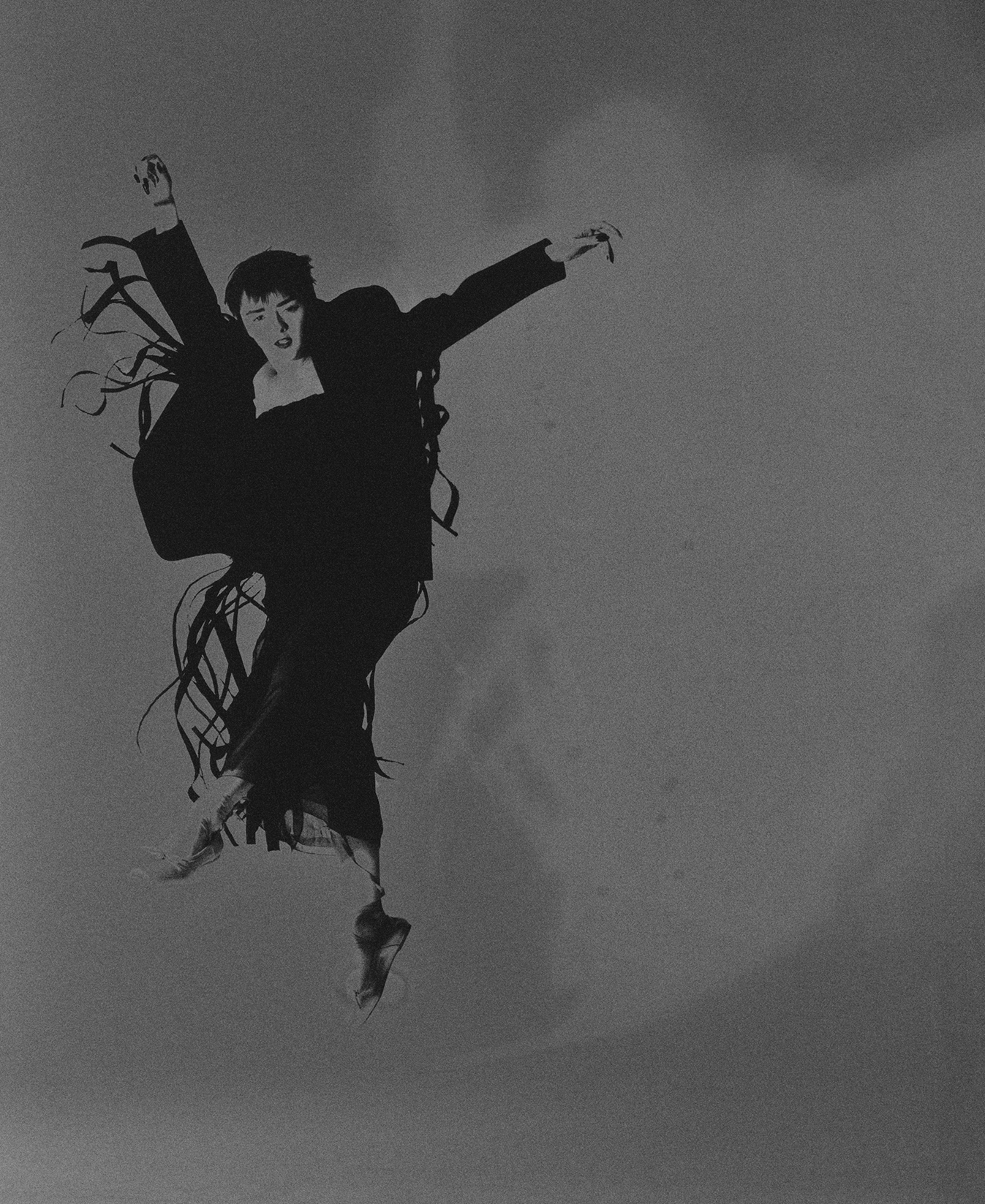

And who better to speak on personal revelation than an actor who’s grown up in the spotlight, a crucible of self-perception? Amidst the distractions of stardom, the Game of Thrones star’s enduring self-confidence has given her something we all should be envious of: she knows who she is, the path she’s on, and how to traverse the unpredictability of life.

With a range of diverse projects under her belt since the finale of Game of Thrones and a highly-anticipated Christian Dior biopic series freshly out on Apple TV, Williams finds herself increasingly grounded by her own private revelations. She takes the time to explain herself, responding directly and without hurry to my deeply personal questions about meditation, social pressure, and self-perception with honesty and an engaged sense of humble self-assuredness.

By the end of our conversation, I felt a sense of illumination from our time together: like my own philosophies around serendipity and the flow of the universe had been truly seen in a rare moment of human connection across screens.

For this feature, I wanted to present William’s thoughts unobstructed by anything more than this introduction. A snapshot of her current state of mind and own private revelations: perception and epiphany in a beautifully clear understanding of the world.

ON FEELING LIKE HER OWN PERSON

I’ve spent a lot of time alone over the last couple of years and I've spent a lot of time on self-development — a lot of yoga, a lot of meditation, a lot of therapy, and a lot of journaling. From a young age, the way I saw myself was dictated mostly by the way that I was seen publicly, but now I really feel like I can see myself for who I am — how people [feel] who are not in the public eye feel.

I used to think of myself as two people, like the famous side of myself and then the normal side, but now I feel like those two people have become one again. I'd say it's been gradual, [coming to my sense of self]. I think that it's definitely been propelled by meditation and yoga practice. Also, [there’s] something that everyone always says: “You turn 25 and then your brain closes over.” During my 26th year, I could really see parts of my personality or decisions from my past or conversations from my past differently. And that's just something that you can't control. It's just part of growing up, I guess. But for me, that was so profound.

ON DRESSING TO REFLECT A SENSE OF SELF

I think that this kind of idea — of “method dressing” — is not something that I invented, but have definitely adopted with [Pistol and New Look]. I think that I really started to focus on doing projects that I really, really loved — I’ve had such an influx of opportunity come in since being on Game of Thrones, which obviously puts me in a very, very fortunate position, but I think — with these two projects in particular — what’s been really nice is just feeling like they’re very aligned with what I want to do and how I want to be seen.

And so the press surrounding that and [the ability] to tailor my looks to the characters that I play has been just a really nice extension of the creativity that comes with my job. There’s not a lot of creative freedom as an actor: I’m not writing the scripts or picking the looks or whatever. So it’s nice to incorporate that level of creativity in dressing for press and for premieres and so on. I think that — really to get to that point, I think I just grew a lot, in [my] confidence in myself. Now I just feel excited to be in control of my image rather than feeling completely overwhelmed by it.

ON FINDING JOY IN THE SMALL MOMENTS

I love the simplicity of life, really. The things that bring me the most joy are just seeing my post lady, going to my local yoga place, and seeing some of the ladies that I practice with there — just real simple things.

I recently had my pipes freeze over, and so I went to my neighbor's house to take a shower, and I felt part of the community in a way that's just very simple and beautiful. I’ve just been nurturing my circle and my world to a point where I find these little synchronicities, which is really beautiful.

I think when you get really famous, your circle gets really small and you get less trusting and you get kind of nervous or whatever, and I think my circle is still very small, but in this beautiful little world that I feel like I’ve built, being able to being humbled by the water pipes and still needing to go and rely on someone such a beautiful detail in life. I was walking over to her house and right above her door there was this shooting star. I’ve never seen a shooting star before in my life, and I just felt like at that moment everything was aligned to where it was supposed to be.

ON TAKING REAL TIME FOR RELATIONSHIPS

At the moment, I feel really drawn towards nurturing incredible friendships and relationships that have been part of my life forever, but have never been a huge part of my daily ritual. Even though I do spend a lot of time alone, I feel like I have so much more trust and love in my friendships. The relationships in my life were always there, but I think I was too worried to call upon them in my time of need. Now I feel so secure with these incredible people who care about me and want beautiful things for me. I’ve always cared about them and wanted beautiful things for them, but it feels like now there’s a really beautiful flow and that trust is very strong when I’m with those people. I think [it comes down to] just making sure that you’re not just seeing someone so that, in your mind, you have crossed that off a list.

If you’re with that person and there’s something happening in their life where they feel you are open enough for them to be able to share those things and vice versa — I think that’s probably one of the key things that changed. I used to be like, “Okay, I’m going to go home. I’m going to see everyone and I’d spend three seconds with everyone that I wanted to see.” And the whole time I was like, “I’ve got to work on Monday and learn my lines and what was the point really, because no one has changed...” It’s [better] to think about those moments being sacred and being something that you put a lot of your time into or that can take up a real permanent space in your mind as [they’re] happening, rather than being stuck in the past or stuck in the future during those interactions.

ON EMBRACING SYNCHRONICITY

I walk my dog in the same place all the time, and I’ve been talking about how I really want to get a lamb because I have a big garden and I’d love to have a little lamb. I was walking and there’s this lady walking towards me with a lamb on a leash, and I was like, “What are the chances that I’ve met that crazy lady who has a pet lamb?”

Yeah, I just think that what I’ve really learned is that these synchronicities have found me in a really beautiful way, and whenever they pop up, now I really have the space to see those tiny little details that bring me the most joy and keep me on the path and make me feel like I’m doing what I’m supposed to be doing. I can trust in that now and not feel like I’m just floating through time and space, never really landing or sticking anywhere, searching for who I am. I now just feel very present in this moment and am really just drinking it in, when these beautiful simple things happen.

ON THE FLOW OF THE UNIVERSE

I used to see myself as very driven and constantly moving and constantly pushing, but now I can just sort of sit and be taken, rather than feeling that frantic energy of I have to make the future happen. I feel like it’s all going to happen the way that it’s supposed to, which is definitely a calmer way to live life and definitely puts a lot less wrinkles on my face and gray hairs on my head, so that’s nice.

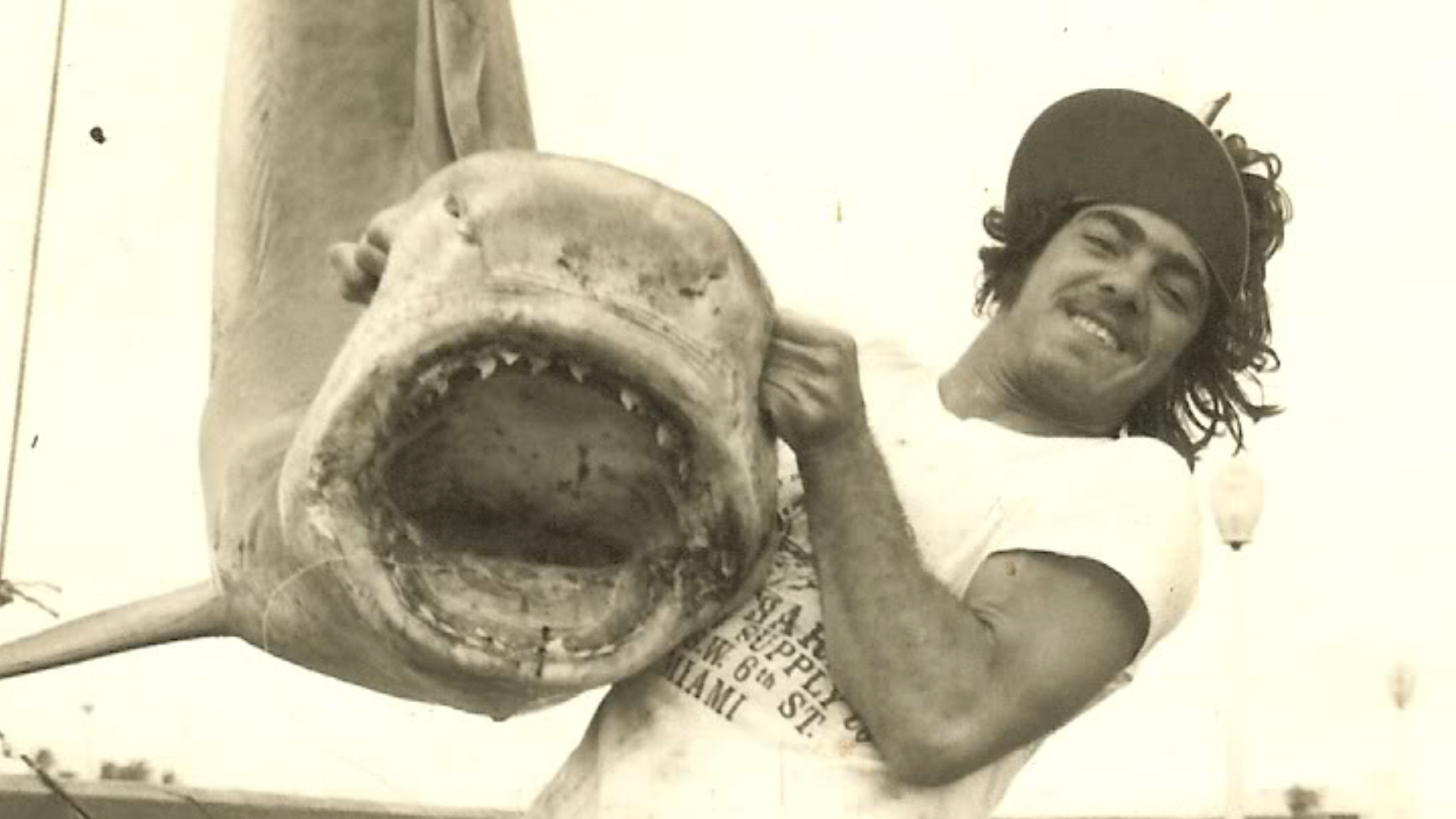

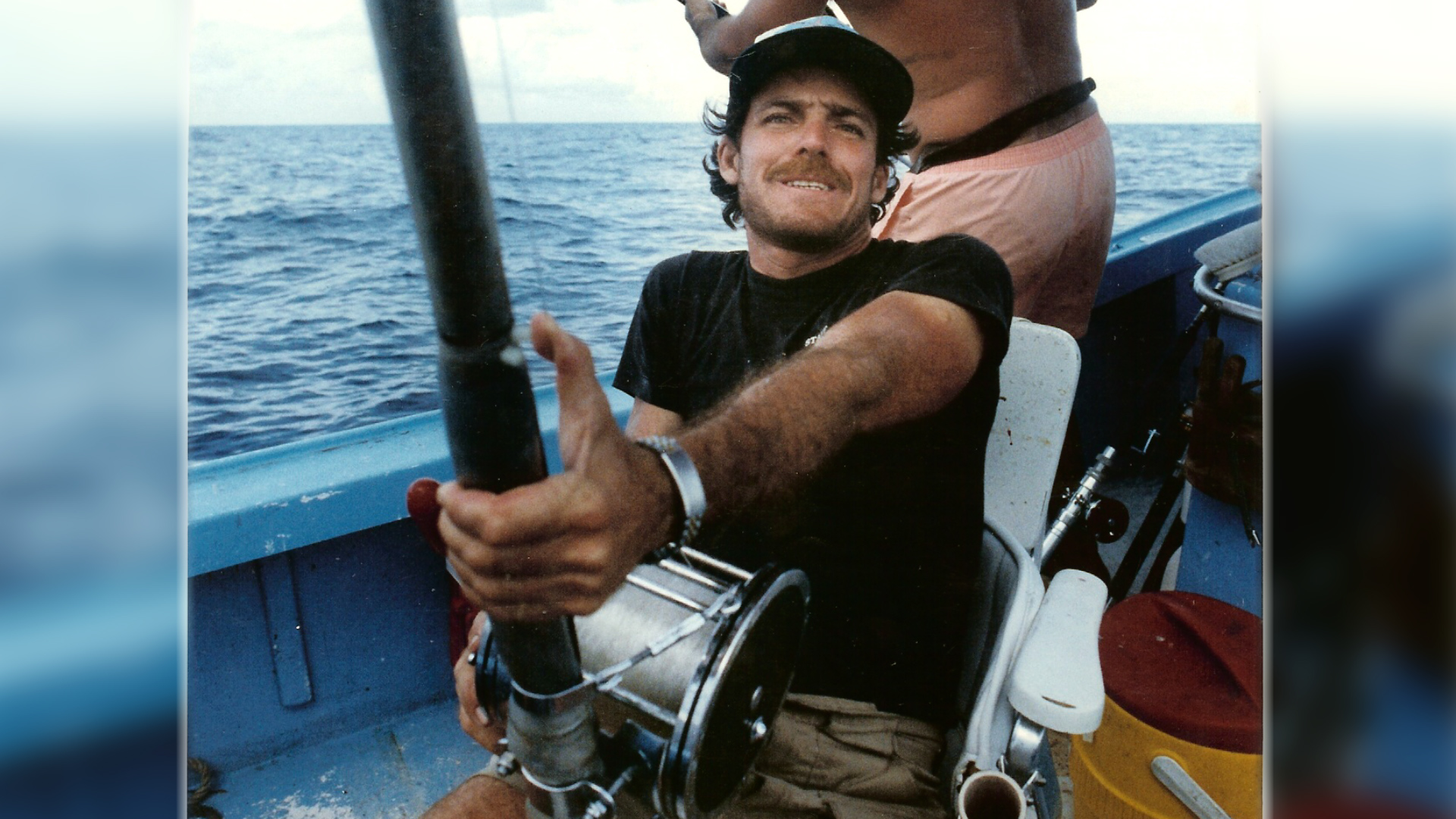

There’s also Shannon “Seaweed” Bustamante Jr., who grew up fishing alongside Rene and his father Shannon “Seaweed” Bustamante. During interviews, he’s seen sitting next to his own son, Dante. We cut between Jimbo, Seaweed Jr., and other locals who knew Rene, who knew South Beach, pictured alongside archival footage of Rene catching and swimming with sharks, interspersed with interviews from local reporters. Shark fishing, or sharking, as a sport, is not something people are generally familiar enough with to think that it would have its own Michael Jordan. But for those who knew him, like Jimbo, Rene was Michael. “I’ve taught a lot of kids, and they become good,” he says, back on the pier, the spitting image of a salty and seasoned sharker. “They become better than me. And Rene was one of them. [He] became one of the greatest shark fisherman in the United States,” Hammer says on the pier. “He proved it every day… he died proving it.”

I grew up in Miami. I attended Marjory Stoneman Douglas Elementary School, named after the journalist turned asexual environmental crusader, and then I went to Miami Dade College for film for two semesters before dropping out. That’s where I met Robbie Ramos, somewhat embarrassingly. The short I made during the first semester somehow made it to the Miami Film Festival student competition. Possessed by the delusions of grandeur that come with being a writer and the God complex of a 21-year-old, you would have thought I was on the red carpet of Cannes the way I acted like my shit didn’t stink. I got wasted at the open bar reception at The Standard on opening night off a pitcher of sangria and tequila shots. I left halfway through Jason Reitman’s “Tully” at the Olympia Theater in Downtown, but it didn’t matter to me. The only thing that mattered to me was the Cinemaslam, the student film screening the next morning.

It was at the Tower Theater in the heart of Little Havana on Calle Ocho. No part of me expected to win. Everyone else was showing thesis projects, but my film was done as part of Film Production 1, which meant we didn’t use sound equipment and couldn’t leave campus. It was exactly what you’d expect in a student film screening. The film that stood out belonged to Robbie and his producer Pedro Gomez. It was the short film version of what became their feature documentary, South Beach Shark Club. I was blown away. I’ve since found that it’s rare to feel that in a theater during a screening.To think something a peer of yours has made isn’t just interesting or technically sound, but also so fucking cool, is special.

South Beach Shark Club won Cinemaslam, of course. Immediately afterward, I went up to congratulate them. To me, they were rock stars who just killed a set. I befriended them. And for the rest of that weekend, the three of us partied like the college students we were. It’s a tradition we’ve more or less continued anytime the three of us find ourselves in some stuffy ‘Miami filmmaker’ this-or-that, which happens more often than you’d think. Between us is a type of kinship, a mutual sense of being an outsider.

When I moved back to Florida, I hit up Pedro and asked if he and Robbie could take me fishing to write about the South Beach Shark Club. They said yes. On this particular Tuesday, it was 86 degrees and blazing hot — but still, not yet humid. A perfect Miami day. We weren’t sure if we’d be able to catch anything, but nevertheless, I’d finally get a feel for what they’d been doing for the last six years.

I. The South Beach Pier Rats

South Beach Shark Club as a documentary is broken down structurally in chapters, like all old fables. It’s a fitting device, because Miami is ultimately a place built on myth.

If you stay on South Beach long enough, you’ll find yourself stepping into a time warp where nothing is new and nothing is old. Miami’s history is in a temporal space trapped in a haunted Art Deco hotel. No one is from there — even myself, who’s from here. A multi-generational family like the Bustamantes is rare. That transient nature adds to the myth, though; it could be 2024 or 1974, and yet it’s still a place where the Latin American and Caribbean political diaspora, the Jewish, Russian, and European emigres, beach hippy weirdos and junkies, artists, and misfits alike swelter together. By mid-June, those who've been crazy enough to make Miami home are desperate enough to escape their suffocating reality of swamp humidity, discovering refuge by haunting the nightclubs of Collins Avenue by the Art Deco Motels, milling about like wispy tipsy ghosts.

After sunset, when everyone else leaves the beach, drunk and pink, a different group of strange characters come out to play. Despite her changing nature, there are points of focus in South Beach that remain unmoving through all the burn and blur. Mac’s Deuce, open since 1926, and owned and operated by Mac Klein from 1964 until his death in 2016, is one. Joe’s Stone Crab, open seasonally since 1913, is another. Those points of focus are all interwoven into the tapestry of the beach’s history, its legacy. Along the sand at night, there lives those who subsist on those excesses and revel in the thrills the beach has to offer: the shark fishers.

Rene De Dios caught his first shark when he was fifteen, in 1971. Not long after, in 1973, the film rights for an unreleased novel by a man named Peter Benchley were sold to Universal Pictures. That novel, Jaws, came out in 1974. Steven Spielberg’s beloved adaptation came out the next summer, in 1975.

After that, fear and fascination with sharks became monocultural. Shark fishing competitions began to take place along the coast, by either land or boat. De Dios, depicted in his early twenties, had assembled a crew nicknamed “The South Beach Pier Rats.” Together, as displayed through the documentary's archival footage, they dominated those tournaments throughout the late seventies up until the mid eighties.

This period ended semi-abruptly in part due to the influx of Cuban immigrants with the Mariel Boatlift in 1980, which, among other factors, induced rising crime rates in South Beach. As the documentary explains, the pier where Rene and South Beach Pier Rats competed went into disarray, and was demolished in 1984.

Tuesday, May 7th, 6:05PM:

It usually takes about four hours to drive south from Central Florida to Miami on I-75. Robbie picks me up in a minivan on 14th and Collins, with Pedro riding shotgun. Robbie is already barefoot, and the two of them are railing cigs and gleefully blasting Jim Croce as we make our way. It’s golden hour and I’m laying on the floor in the backseat, letting the breeze hit me.

Once we park on 30th and Collins, we stop to get some supplies, before heading down to meet up with Seaweed Jr. We go to the mini mart for 3 six-packs of Stella Artois and a couple of packs of yellow American Spirit cigarettes, all the supplies we needed for a day spent attempting to do something objectively silly: catch some sharks.

II. The Great Shark Hunt

The second act of the South Beach Shark Club documentary begins in the present with the narration of our very own Seaweed Jr. He passionately discusses the importance of keeping the legacy of his father and Rene alive. On an overcast day, he’s filmed alongside his son, Dante. Off the bridge, they hook a small reef shark.

Back in 1984, the demolition of the South Beach Pier forced Rene and the South Beach Pier Rats to fishing start from bridges. Like rats, they subsisted because they could adapt. Still, the wave of shark fascination had peaked. Younger competitors were few and far between, and there were less competitions due to the rise of animal rights activism (shark fishers in this time did not practice catch and release). This loss darkened Rene with frustrations. Despite this downturn in his culture, in the 1990s, Rene was said to have caught a great white shark off the shore of the Bahamas. This would’ve been the fishing maestro’s first great white, and as the myth goes, the weight of the shark caused the boat to begin to capsize. The captain is said to have wanted to cut the line and save the boat, but Rene apparently threatened to kill him if he did. The boat sank. Rene supposedly didn’t retain the great white. We’re shown press clippings about a boat sinking in the Bahamas due to a shark. Did it happen? Captain Louie, interviewed in the doc, was with him.

He says it happened. It’s certainly one hell of a story.

Tuesday, May 7th, 7:13 PM:

We joined Seaweed Jr on the beach off 36th. He is accompanied by his son Dante’s youth football league, the "Shores Spartans" — for whom Seaweed Jr is the assistant coach — and their families, as well as other fish enthusiasts. They’re setting these huge gauged fishing rods in the sand. It’s supposed to take a while, and we don’t even know if we’re going to catch anything, try as we might. Part of the reason it took several years for the feature film to get made, they tell, me, was the slim chance of catching a shark on schedule for production in a place that rains 70% of the year.

Robbie, growing up on the beach, learned to shark fish himself from his father and uncle Jorge — who recently passed away and was also featured in the documentary. He met Rene when he was growing up in Florida, as well as Captain Louie, the head of the Shark Club and the captain who witnessed the Great White Incident. As Robbie recounts, he and his uncle Jorge were on a fishing trip, sleeping on the bed of his pickup truck for three days. They stumbled upon the kindred spirit Captain Louie, who let them sleep in his RV. Three days turned into a weeklong excursion, and on one particular night, Robbie remembers Captain Louie convincing his uncle, who didn’t smoke weed regularly, to have a joint with them. Captain Louie and Jorge got high and were in great spirits recounting old stories about Rene, transcendent fables that were cinematic in scope and danger. “That’s when I knew it was a movie,” he said. Afterwards, Robbie did some digging on the internet, dove into some rabbit holes, and unearthed some leads.

In 2014, at a Miami Dade College screenwriting class, Robbie met Cuban born Pedro Gomez. They went for beers after class and Robbie showed Pedro footage of Rene. Pedro was immediately enthralled by the story, and the pair started hitting up the Wolfson Archives to find old media on South Beach history and fishing.

Back on the beach, I question Robbie on the likelihood of us nailing the big game, and how the beach here compared to others. “On a normal beach, there’s a trough,” Robbie says, which is a long, narrow dip in the shoreline. Miami Beach doesn’t have one. “This is all fake beach. The beach actually starts over there where the sand is. We buried a coral reef here in Miami Beach. Well, the municipal government of Miami Beach did without anyone’s permission. The reef is right here, underneath the ground.” He points down to our toes, half hidden in the sand.

They bring out the kayak. Someone gets in and paddles out to drop the bait. In the distance, there’s a battleship. It’s a dystopic omen on the horizon of an otherwise beautiful day at the beach. Robbie tells me it’s for Memorial Day. The kayaker returns unable to drop the bait. Seaweed Jr goes next. He paddles out past the wave break, seemingly towards the giant battleship on a kayak, as Dante and the Spartans play in the Shallow. Such is the tedious process of shark fishing.

III. Legacy of the Mentor

Eventually, Jimbo started to mentor him, like he did with Rene. If he hadn’t, as he says in an interview on screen documentary, it would have been easy for him to gravitate to a life of crime. This was the era of Cocaine Cowboys and gang activity in South Florida. Seaweed Jr. explains how the South Beach Posse became a persistent presence in the neighborhood. A newscaster in archival footage describes this era of South Florida as a teenage war zone. The version of the man Seaweed Jr. describes that he could have been is a far cry for the man he is today, an admirable father, and coach, a mentor.

In 2003, Rene and Jimbo went fishing in Key West. Rene had a minor stroke and was taken to the hospital. Rene asked Jimbo to take him out of the hospital against the doctor’s request. Rene and Jimbo went back to the Seven Mile Bridge. He caught a shark. Rene died a few days later. Such is the legend.

South Beach Shark Club tells us Rene De Dios is unmatched in shark fishing excellence, this irrational, wearisome, glory filled sport. Unlike Rene, who wanted to be the best, Jimbo wanted to fish. He wanted others to fish. I watch a turtle swim next to him as he paddles to drop bait.

The filmmakers reminded us that legends depend on legacy. It’s why the South Beach Pier Rats moved to bridges after the pier was demolished. It’s why when the shark fishers come out these days, they catch to release. Legacies adapt to persist through change.

Tuesday, May 7th, 8:00PM:

“So basically…. When I hook big sharks, these kids, my football team… I’ll put in low gear and the skinniest eighty pound kid could reel in a thousand pound shark with no problem.” Seaweed Jr. explains. This is because he uses a rod from the 70’s, a technological marvel that comes with two gears and sounds like a car engine due to its complex mechanics.

Robbie and Shannon share stories about growing up on South Beach, about hanging out by the Marina, about…

Click. Click. Click.

Something! Is it a shark? There's a palpable excitement coursing through everyone. Seaweed Jr. thinks it’s definitely a shark. “I’m calling a small hammer,” he says. Because of the low gear, Seaweed lets all the kids take turns at reeling it in.

It wasn’t a hammerhead, as Shannon thought. It was a small blacktip shark. He came ashore with black marbled eyes, a hook in his mouth, wiggling around and fighting like hell. We all move back while the sharkers try to get a hold of him. “Yo!” Seaweed calls out to me. “You got your camera?” He gathers his football team to flank him as he holds down the black tip, still writhing in the sand. I snap the photo. “Move back!” The kids scatter as Seaweed Jr. drags the shark into the water with him, past the current, releasing him back into the sea.

A perfect catch and release.

“Those kids are going to feel so fucking cool tomorrow in school. Like, yeah, I saw a guy catch a shark last night!” Robbie says. He’s right. Everyone there that night has a story to tell.