Carlos Martí and Sabrina Ol are Finding Order in Confusion

office sat down with Martí and Ol to discuss the adventure they took to Mercado de Senora, the photography process, and the surrealism that drives both the market and their culture as a whole, below.

Carlos, what did you learn from your years of fashion photography? How did you translate it to this project, and in what ways did the medium also limit you?

Carlos Martí— Well, now I think more about aesthetics. I used to do more street photography — that was the thing that I was focused on all my life, just taking my camera and walking and shooting around. I wasn't really focused on an aesthetic. I think fashion photography gave me sort of a narrow point of view. But it also taught me that it's not actually about fashion at all, it's about capturing a moment and trying to engage with people through it.

I can see how that aesthetic carries over, but there are different nuances in both subjects. In what ways did you and Sabrina bounce off of each other and collaborate for Micromorfosis?

Sabrina Ol— I think the community here in Mexico is very collaborative and we're always trying to help each other and push each other. When we started talking about the collaboration, one of the things that we both were trying to exercise was the idea of creating pictures that didn't necessarily have to do with a model wearing clothes. Because, of course, I have a fashion brand. I tend to mostly shoot pictures of people wearing my clothes. I was interested in communicating feeling without having another person on the other side of the camera. Actually composing a vibe with different elements, together with Carlos. And one of our starting points was the Sonora market and trying to get inspired by all these sounds, textures, smells, and people. We tried to recreate a ritual, or it felt that way almost. When we were composing all of the little elements, it felt like a very collaborative moment. We had a lot of control, but we also learned to trust each other and let go of that control.

Mercado de Sonora is the largest herbalist and esoteric market in the world where you explored unique subjects for this project. What are some of the most outlandish things you can find at the market?

SO — The bones were crazy.

CM — They just have everything there. They have the feathers of the most exotic birds that you can find. Bones from every animal. What Sabrina said is so true because it felt like this continuous ritual from the market to the final pictures. It's a very eclectic place.

SO — There used to be ever more available there. There are probably some illegal things being sold, but if you ask, they'll bring it to you.

CM — You get to the point where you lose yourself. After a certain point, you're walking around and you realize you don't even know where you're going anymore.

In what ways are the smells, sights, and sounds of Mercado de Sonora indicative of broader Mexican culture?

SO — Markets in general represent, visually and aesthetically, a lot of parts that explain how the country works. Many aspects of how the country works, politically and economically, definitely have that surrealistic aspect.

CM — Yes, markets in Mexico represent Mexico itself.

SO — It's very creative because it comes from a lack of space or lack of resources. There are very surreal decisions that happen here politically and economically. I think magical realism is the best way of explaining how Mexico and Latin America work. The only way of explaining it all is by putting a little bit of magic into everything and being really abstract with our words because sometimes it's impossible to translate. So going back to the market, it just represents everything — it represents surrealism and it represents order in a messy environment.

CM — And spontaneity.

SO — It represents a culture, unity, and how everyone is helping each other out. It shows that there is some kind of order in the mess, you know?

CM — You're right Sabrina, the Mercados in Mexico are kind of like an anarchist situation, but everybody's hustling and everybody has their place. It's a small representation of the whole country.

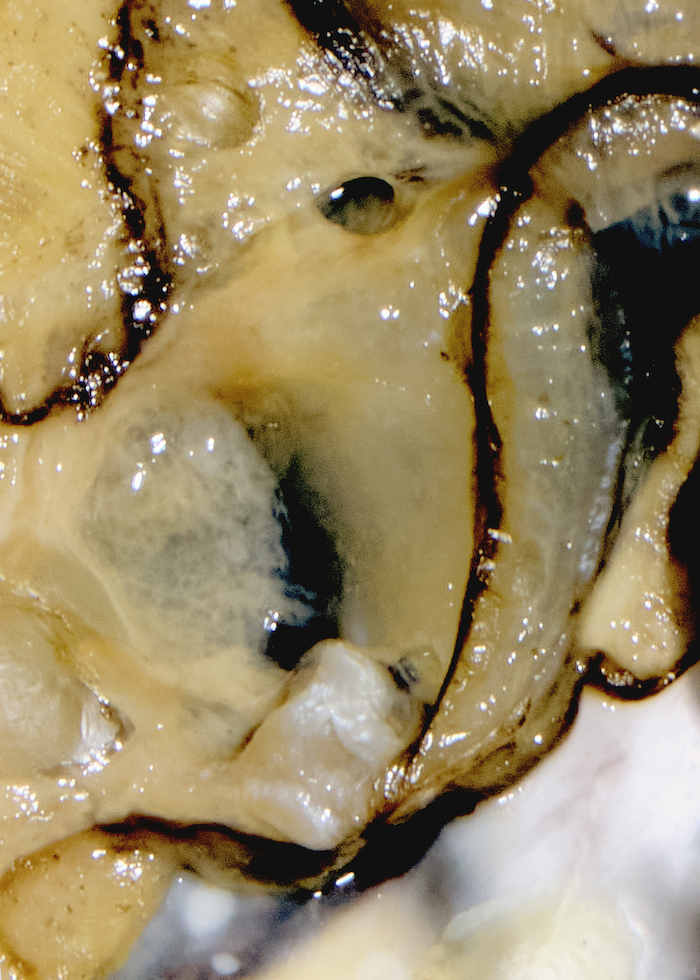

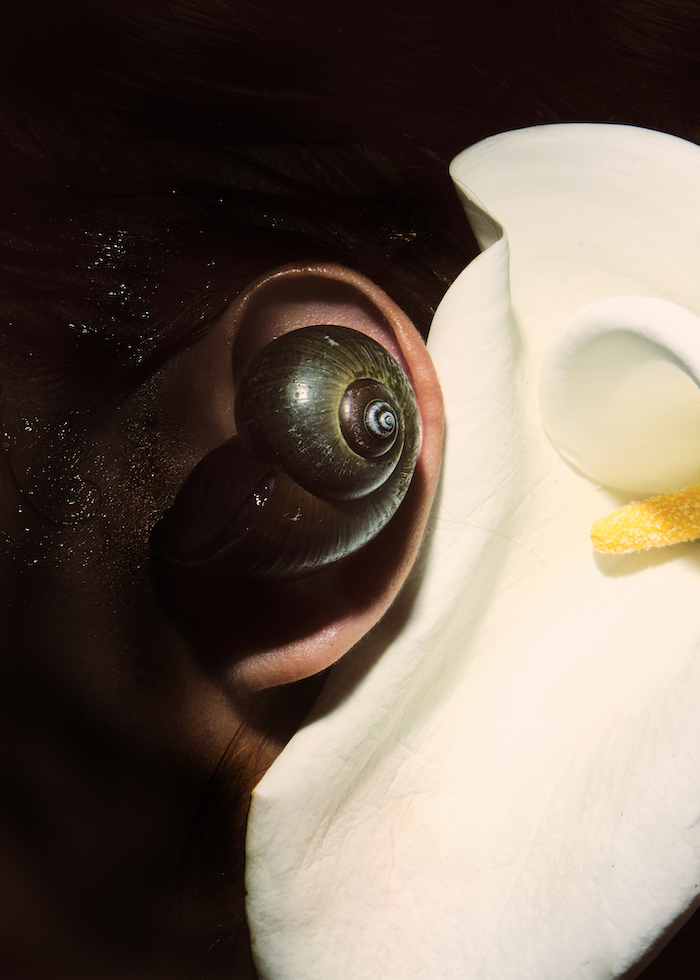

I think that notion of order in disorder paints a really detailed visual. And that translates through the photos as well. Tell us a bit more about the photography process — from conceptualization to execution. What challenges did you face in photographing these unique subjects?

CM — For me, finding focus was difficult. It's difficult to remove yourself from the process and look at it from the outside to actually identify the frame of it. We were in this flow of composing so many different elements. So I think the hard part was definitely finding focus.

SO — Definitely. Carlos would keep saying, 'Okay, we have all these elements, but what is the core? What is the spine of what we wanna communicate?' And I feel like he was definitely really good at discovering that structure and that core that made it all make sense.

I think that's kind of the hardest part of making anything — removing yourself from it and seeing it in an objective way. That's really difficult to be able to do. And with so many moving parts as you said, I bet that was challenging.

CM — But that's photography always, you know? You have to stop everything. You stop the universe and then you have to step aside and look at it from afar.

SO — I constantly have these big ideas, but I feel that's part of what I do. Part of my aesthetic is to be a little bit messy with my work, but it ends up making sense for me and for other people too. I definitely feel like as I grow and mature in my work and my process, I have come to have more anticipation. I've learned to simplify my ideas and we were able to do that really well as a team.

I know a big part of that process was choosing elements that evoked this sensory experience for audiences. How do you think senses like smell and texture elevate a photograph?

CM — Well, in this case, it was especially crazy. In the market, our senses were all over the place. There were animal pheromones and smells from everything being sold, like fish.

SO — We were there for maybe two hours and I remember moments where I had to push myself to stay there longer.

CM — It was really draining, energetically. We wanted to translate that energy into the project. When I started photography, I started because of music. It was a synesthetic process for me. I started my own kind of ritual and it was always the same ritual, listening to this hardcore music and just putting myself out of my head. And then the images came along totally just by themselves. It kind of translated the music into pictures. So we did the same thing with the market, just on a bit of a more complex level because there were so many inputs. A lot of colors, sounds, and smells. The senses are universal translators.

The photos are very visceral, which is what I love about them. The idea of sensory experiences also being a universal translator is really interesting because it helps people to connect to the photographs in this really high-level way. The photos you composed are alluring, yet uncanny at the same time. What feelings did intend for these compositions to stir in audiences? Or is the interpretation intended to be multifarious?

CM — Well, we were just like kids having fun. We didn't consider too much how they'd be received. At the moment, we were just playing around with the images. At the time, the images weren't even the point, but it was that experience we shared.

SO — But I do think that you were going for a very specific thing when you were composing the images. Definitely a darker side of the market — that visceral element that you mentioned. You don't see Micromorfosis and think about community and laughs and love; you think about the insides of the market.

As many of the plants and items for sale are used for “amarres” or love spells — mysticism is embedded in the DNA of Mercado de Sonora. Do you believe that amarres truly work?

SO — The energy there is so strong. I wouldn't say it's a myth at all just because of how I felt. I remember telling Carlos at the end of our trip, 'I feel like I'm gonna pass out.' Just because of all of the smells, noises, people screaming and selling their inventories, and the visual stimulation. In Mexico, especially with colonization, there's so much history buried underneath all the streets. I feel like it definitely has strong energy on top of that. And then the next day we took the pictures, so we brought all that energy I felt from the market. I think I'm pretty susceptible to certain environments; I think Carlos is too. We were both tripping, literally. I feel at the beginning, when we got there, I could differentiate one thing from the other. But by the end of our visit, that got harder to do.

Which is really unique because even for someone like me who has not been there or seen the market, you can feel the photos. It feels like a behind-the-scenes of the market. Although the creative process may have been more free-flowing, now that you have this collection of photos and they will be able to be seen by audiences, how would you describe the realm you want your colorful photos to transport audiences to?

SO — For me, I would hope they go to a completely alternative, surreal world where colors are different and things aren't what they seem. I would hope people have a lot of questions about what things are because, at the end of the day, the theme and title of the project is Micromorfosis. It's like these small universes composed of all these different elements. I would want people to question it, be introspective, and try to make sense of it. I think the photos can represent moods or emotions even. I love to hear what people think we're trying to say. That's one of my favorite things about creating, it's hearing what other people thought. And sometimes they tell you things that you didn't even think about, but you're like, 'Oh, that actually totally makes sense.'

CM — I like the confusion part of it. I want people to look at it and think, 'What is happening here?' This calm state moment of no sound or context — just confusion.

I think that the abstractness of the photos is also one of the biggest parts of their allure. Maybe people don't have to come to an outcome after looking at them, but I think that mystery is what draws you in initially.

SO — I have this friend who writes poetry and she's always like, 'You don't always have to try to understand poetry. You just have to feel it.' So with these pictures, maybe it's about just accepting them in that same way.