Casey Bolding's Temporal Reflections

Bolding’s attraction to gestures of chance and accident can be attributed to his close studies of the highest arena of 20th century German cultural wars, where deskilled conceptual painters like Jutta Koether and Charline von Heyl, closely associated with the underground art scenes of Cologne and Dusseldorf, vigorously attacked conservative representational regimes within the established art world and quickly ascended into stardom. The lyricism and collaborative impulse found in Casey’s paintings could be traced back to Milton Avery, whose fondness for unrestrained use of colors and expressionist figuration lifted the American tradition of abstraction out of obscurity and into European museums. But perhaps the most fascinating of all of Casey’s influences is the most lowbrow: his time spent working for his uncle’s faux finishing company that covers the plain walls of middle-class households in Colorado with Tuscan style decorative patterns.

When Bolding invited me to his solo exhibition, I went in with a reluctant curiosity, as I have been a fan of his practice for a while but remained wary of how art history tends to monumentalize white male painters and mercifully allows for their self-mythologization. After an hour, I came out of the meeting with a completely different understanding of Bolding’s position within the art world. He is candid without being contrarian and sincere without being pretentious, seemingly propelled by a tender attention to social relations and concerns that often fall outside the priorities of the New York gallery circuit.

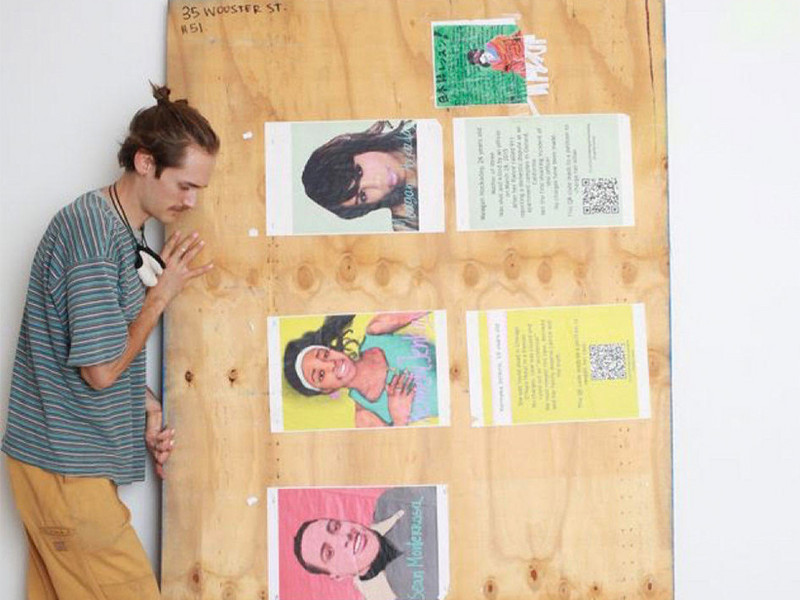

Bolding professed that he never quite anticipated the level of success he would have today. Coming from a suburban town south of Denver where “very few people had the resources to make it out,” Bolding’s upbringing foreclosed art school as a possibility. “No, this is crazy,” was Bolding’s instinctive reaction when he heard for the first time how much art school would cost, “I am not going to enter my adult life with a huge amount of debt.” Though he admits to being “untrained in some ways,” Bolding still insists that he could never claim to be an outsider. Indeed, it is perhaps more accurate to say that Bolding is a self-taught artist who has been rapidly pulled into the inner circles of the art world after nearly a decade of receiving little curatorial attention. After a group exhibition at Mammoth in the summer of 2023, Bolding was selected by artist-turned-gallerists Ted Targett and Anna Eaves for another group show hosted at Shoot the Lobster in late 2023. Soon after, he was approached by dealer Polina Berlin for a studio visit and she offered his first solo show.

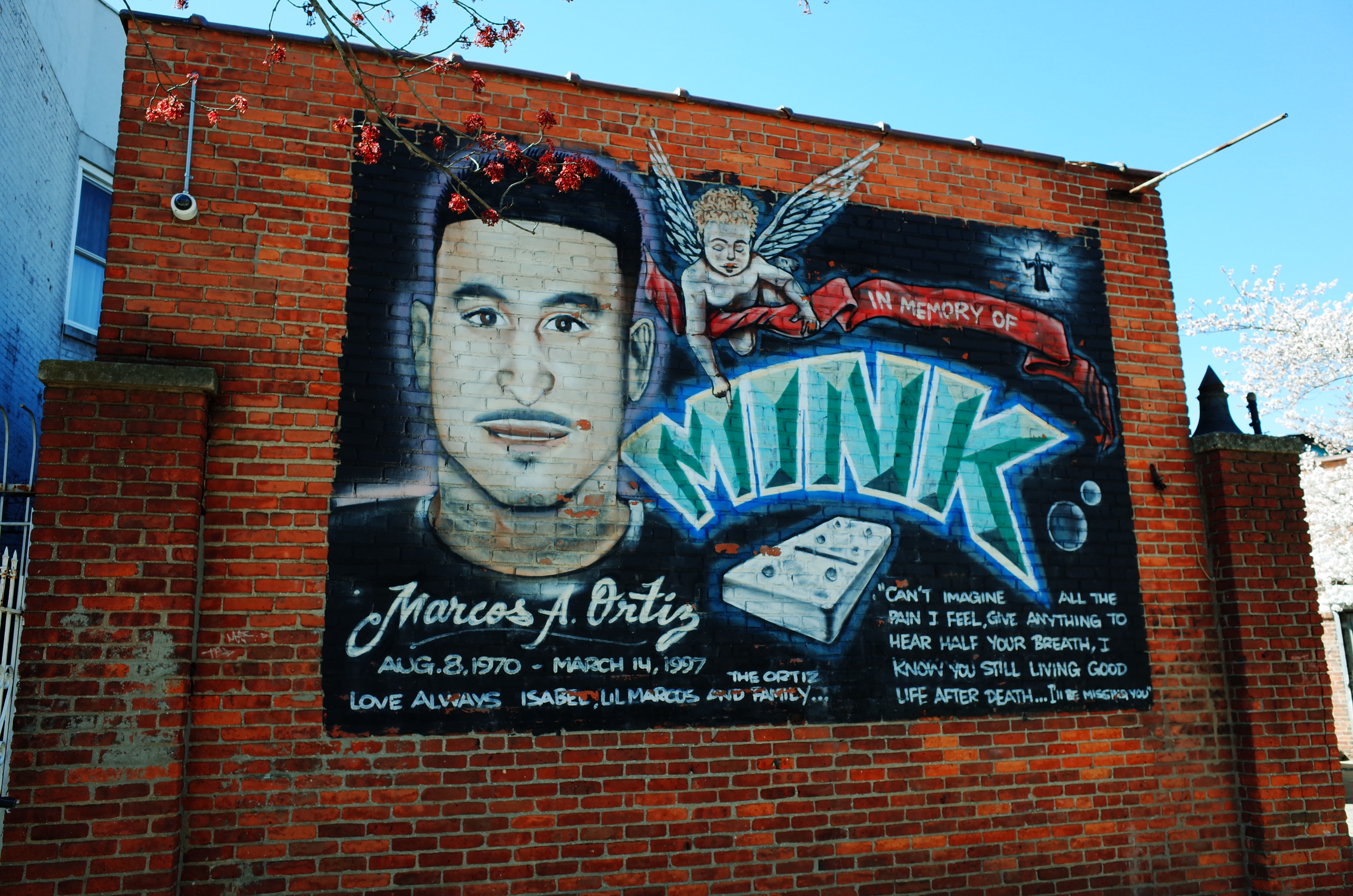

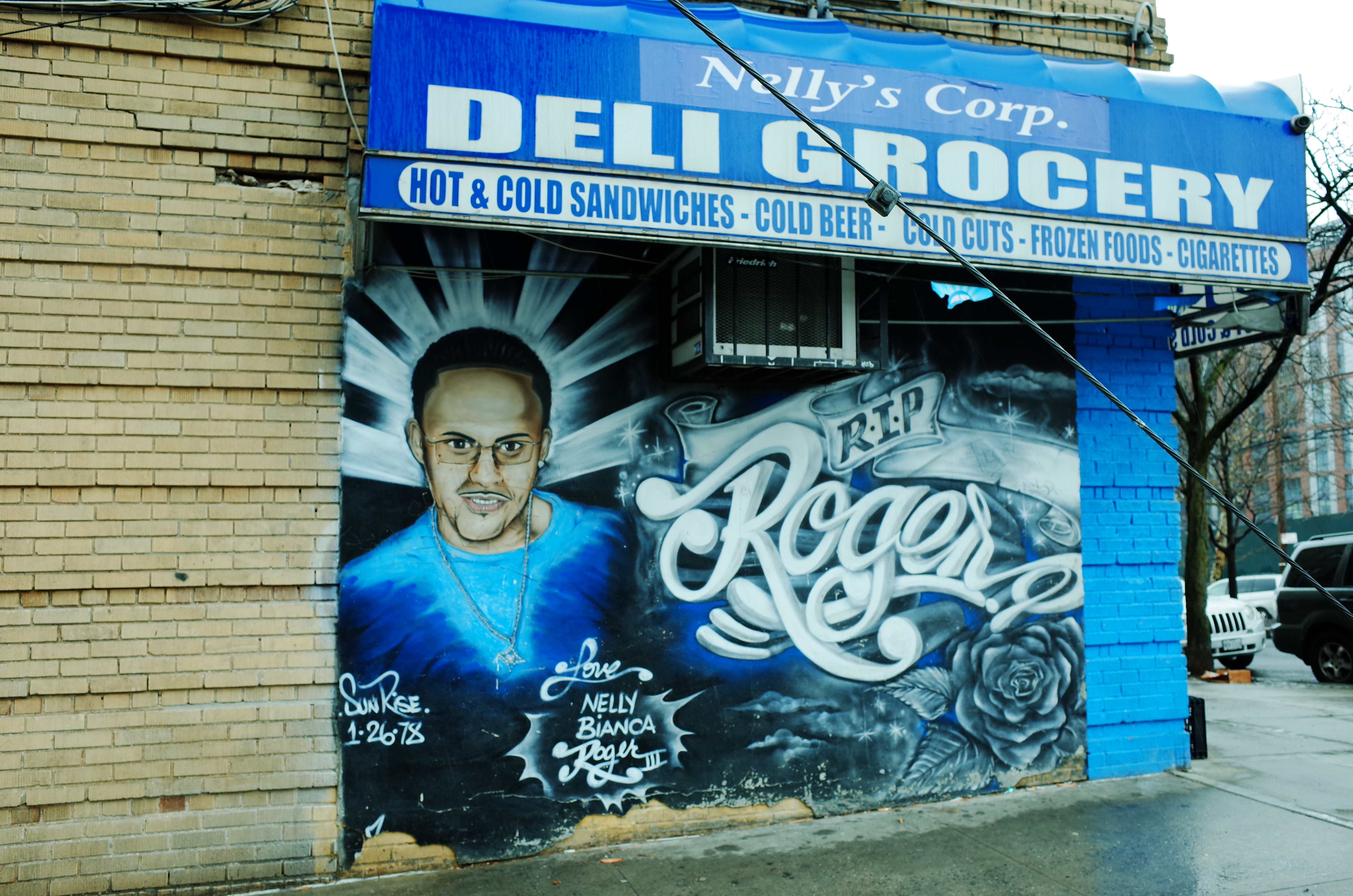

Upon graduating high school, Bolding threw himself into the graffiti and skateboarding scene in Colorado. Trains were his main target. Seduced by New York with its more robust graffiti scene, Bolding moved to Brooklyn in 2013. He made a living by working at a print shop in Williamsburg and freelancing for various mural projects. Developing his practice in his free time, Bolding would spray paint graffiti inside abandoned buildings, where he did not have to “fight for space or worry about trashing some pieces of New York history.” When I asked Bolding if he was thinking about the validation of art institutions, Bolding maintained that he just felt like he needed to paint, given his access. “I often ended up with a bunch of materials from my uncle that would otherwise go bad,” he says.

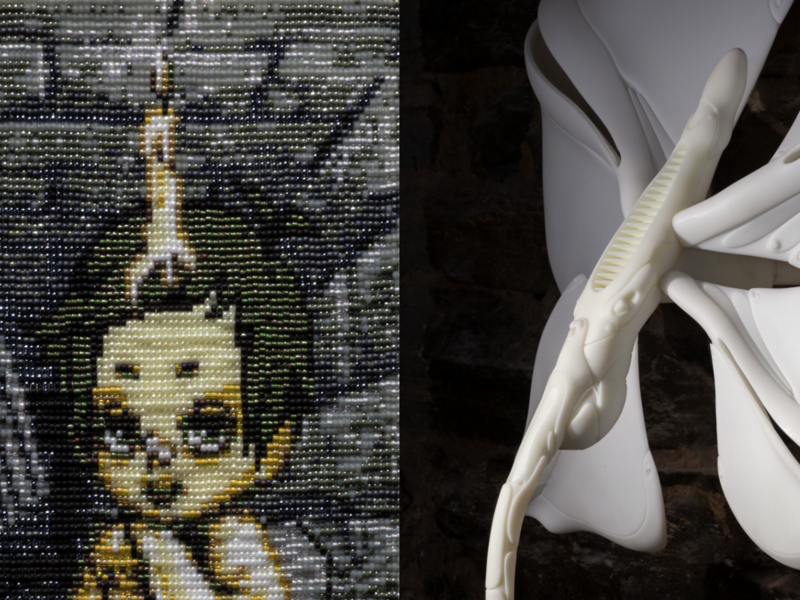

Bolding’s style is indebted to graffiti culture and his years spent painting economically, and it manifests clearly in his works. In some, traces of paint dripping down are visible and exposed, and textured surfaces give the impression that these paintings were just scraped off a wall. At the same time, Bolding tries to veer away from the literal and explicit communication of graffiti, instead choosing to convey a psychological landscape that is ambiguous and ambivalent. Haphazard torsos blend into the background, twisted, bent over, and charged with tensions. Faceless, out of focus figures recur and turn away from the gaze of the viewer. Rare cases of frontal figuration are troubled by their ominous double.

In Bolding’s paintings, I also sense a thin veneer of otherworldly time. The kitschy, rustic feeling of faux finish is transformed into a poetics of unpristine sedimentation that takes on a durational element. Working with photographs — sometimes of family members, and sometimes of random children on the streets of Lower East Side — that have a particular temporality, Bolding’s brushstroke transforms them into moments of disquietude and pleasure, evoking universal archetypes and sitting outside of time. Mulling over these appropriated images intensely, Bolding’s constantly applies layers of oil, acrylic, flashe, and plaster on his canvases and then strips, sands, and trims them away, with the intuitive conviction that the source of the image becomes all the more effectively clear in this process.

Bolding can be quite sentimental about the objects he has collected and the people he has encountered. Yet, he does not seek to glamorize — or celebrate, per the tradition of portraiture painting — everyday life; rather, he favors a guerilla and confrontational approach with the immediacy of lived experience. In one painting, Bolding grapples with the nature of remembrance, using an Ikea bedspread as a tactile site of information both condensed and lost. Working with a former lover that is now no longer present in his life, Bolding hung the comforter on the wall and put a sheet of plastic over it. Together, they painted directly on the plastic,and then ran across the room to transfer the paint from the plastic sheet onto the actual canvas. While the details of the event cannot be recounted from merely viewing the work, traces of the co-creation can still be felt. In fact, this is one of Bolding’s favorite ways to paint. “I like finding shortcuts,” he confesses “I want viewers to look at my painting and feel like they can do it too.”

Bolding is looking forward to keeping painting and working with galleries, but he also anticipates more time spent with graffiti friends on murals. That isn’t to say he does not care about the allures of art world glamor and commercial success; rather, these achievements allow him to focus on what he truly wants and needs to do. The afternoon when we met he was in a well-worn t-shirt with exposed seams, several holes, and spots of paint residue, a perfect witness to Bolding’s personal history as a devoted painter. That t-shirt felt partially illustrative of why Bolding enacts the desire to paint — to document his devotion to painting itself.