Caught in a Dream

Now, the London-based singer is set to release her debut album, Ancestor Boy, on March 22. If singles like “Daddy” and its accompanying music video are any hint at what’s to come, the album will be dope AF, full of the dreamy kind of spiritual urgency for which Lafawndah has become known, and lyrics narrated by both the real and imagined figures writes—including wisdom from younger self.

“My new album is full of cycles—life, death, rebirth, big cycles and mini-cycles,” says the singer. “It’s the story of the ancient-future.”

On the phone from London, Lafawndah told us about her upcoming record, connecting with the past and what it means for her future. Read our interview, below.

Walk me through the creation of Ancestor Boy.

My creative process involves making everything in short, concentrated amounts of time. So, I locked myself up for 20 hours each day without sunlight—complete isolation. I started by creating the sonic world of the album because I can’t sing if the composition isn’t exciting to me. The record had a life of its own for three years. I traveled to many places and let it expand—each time shit happened, I wrote more songs. But making this album really felt like a family affair, because it involved everyone I love. I didn’t make it in the industry way, with scheduled studio sessions. Some of the people who helped me aren’t even musicians—hey’re just people who know my history, who would tell me a story and give me inspiration for a line.

How did you find the voice to finish it?

There are many narrators in the album. There is a song that’s me at five years old and me after I die. There are even people that don’t like me narrating songs.

Do we get to learn more about your personal life through your lyrics?

My new project is intimate. I’ve put my family story under the microscope—how I grew up, where I come from, who raised me, who died, who stayed and what they passed on. I also talk about the fact that I put myself in a research bubble for a few years around world history. I like to think about how we got here on several levels—morally, economically, and through the movement of people.

Where did you end up actually recording?

All over the world.

Was that important to the process?

Yes. I didn’t have a house or a home for almost seven years. I only moved to London about three weeks ago. I feel good here and I think I want to stay forever. But the album addresses the nomadic life that I had when I felt like I couldn’t stay in one place, or that I’d ever feel good or satisfied anywhere. A lot of the sounds on the album mirror the energy of being here and there, sleeping on planes and always moving around. I don’t think the album should belong to any one place.

What makes London feel like home?

London is the capital of brown people in the Western world. It’s one of the few places where we can thrive and where we run the city culturally. There are a lot of middle class brown people, which is a relief when you come from a place like France, where that is absolutely not the case.

You’ve lived in cities all around the world, including New York. What was your experience like in America?

I needed to spend time in America. I’m grateful that I got to live there because I gained perspective and confidence. But I reached a point where the things that were, and are, happening there became extremely heavy, even though they weren’t mine. I’m inspired by what I see and hear in London—the city has so much to say right now. And the values here feel more human than what I experienced in the U.S.—there’s a strong sense of community and everyone who is engaged in some creative endeavor wants to see their neighbors win.

You collaborated with director Partel Oliva and Japanese composer Midori Takada on the fashion film Le Renard Bleu for Kenzo and created a mix for the brand’s S/S ‘18 show. What excites you most about the fashion world?

There are projects I do for money and projects I do for personal reasons. Kenzo is an intersection of both. I’ve done so much with Kenzo because I admire and love the people there, and they’ve given me the freedom to be me. I genuinely love composing music for fashion films, making music for runway shows and being behind the scenes. Plus, I like creating relationships because I’ll always need to be dressed on stage.

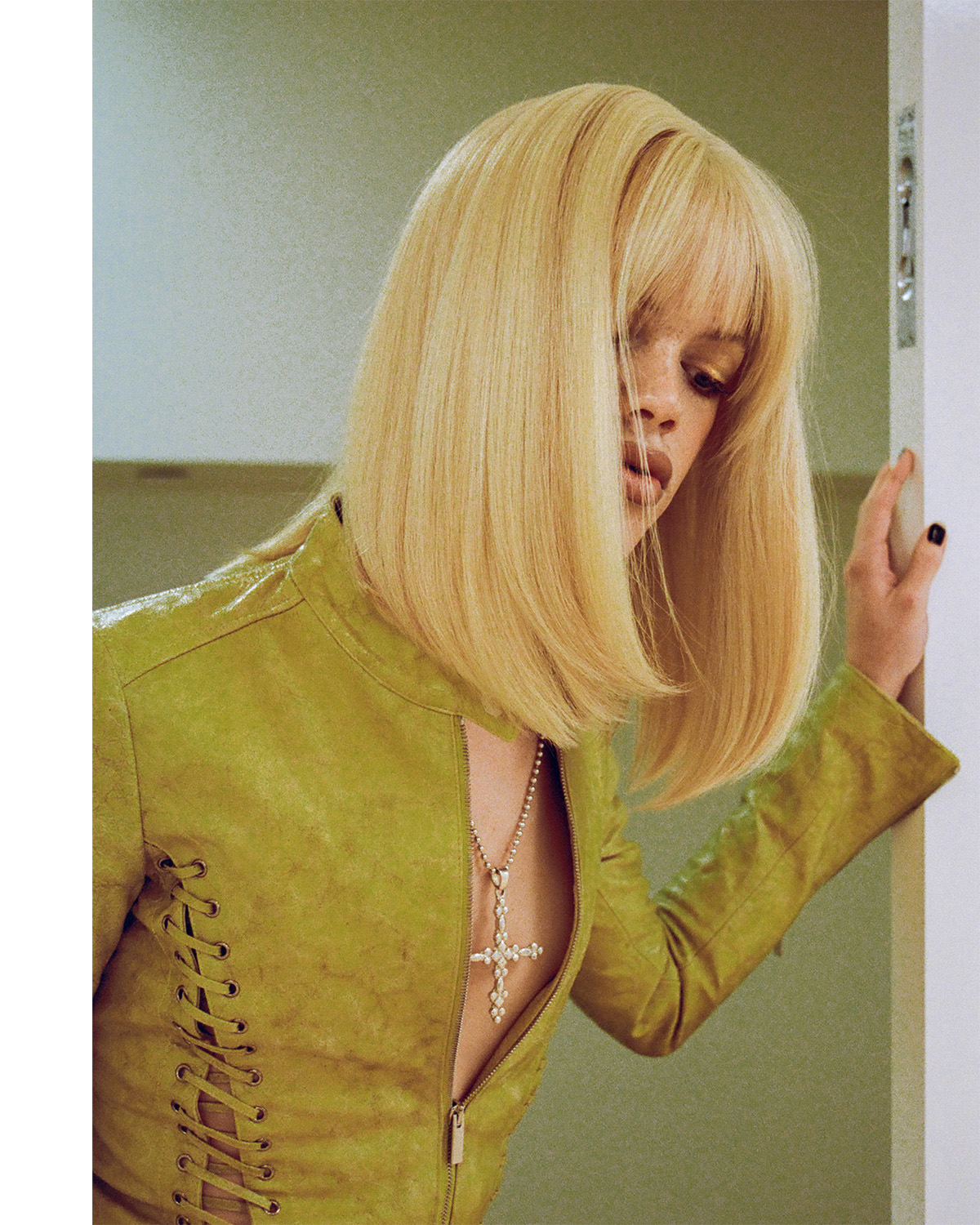

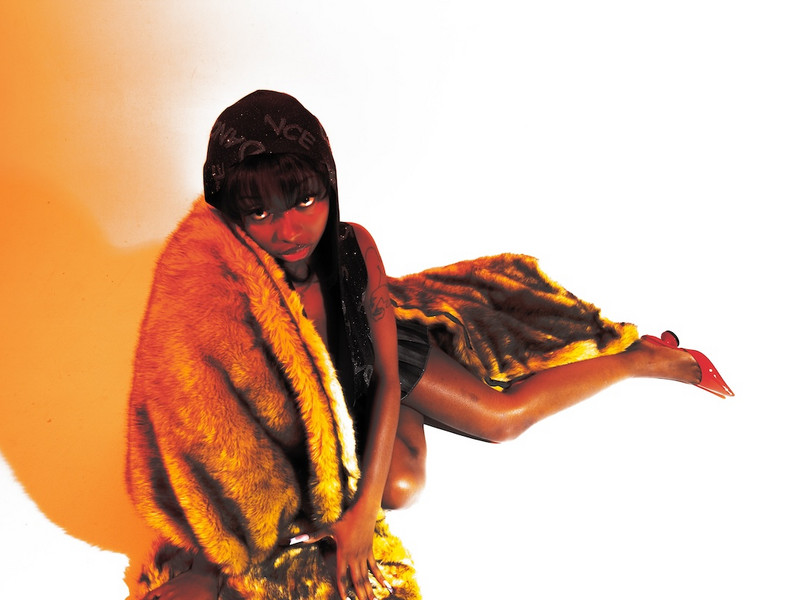

Your artistry involves a lot of spectacle. Even on the new album cover, you’re wearing a bodysuit by NIHL that was originally modeled on a man, and a massive colorful hair piece.

I think that the way I decorate my hair, my body and my costumes are completely integrated—it's all storytelling. Think about the narratives of older mediums like folk music—for me, the hair and the costumes embody the narrator as well as the characters in the story. It also forms a few degrees of separation—I’m not interested in realism or replicating real life.

What scares you about the industry right now?

People believe that the louder you are about your beliefs, the more social capital and more money you get. That’s terrifying to me. Do the actual work silently. You don’t need to brag about it. It’s important to me that the messages in my songs get extended into real life—not just Instagram posts. My music is present in who I hire, where I shop, where I bank, etc.

You’ve been called a political artist. What does it mean to you to be a politically engaged artist in 2019?

I feel like today, especially, political engagement is so commodified. It’s a very sad state and makes the people who have things to say part of the mixed bag of capitalism. It’s capitalism cannibalizing itself. Now people feel like they can dictate what artists should be talking about. But don’t need to talk about my politics explicitly—I’ve done an album and you can dig into them there.

‘Ancestor Boy’ drops March 22. Pre-order it here.