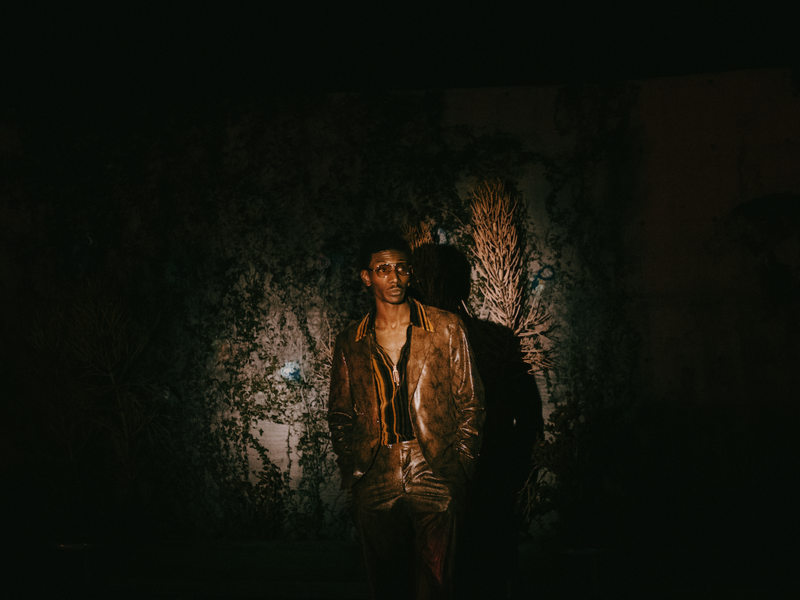

Chanel Beads: Sounds Tailored to Human Imperfection & Feeling

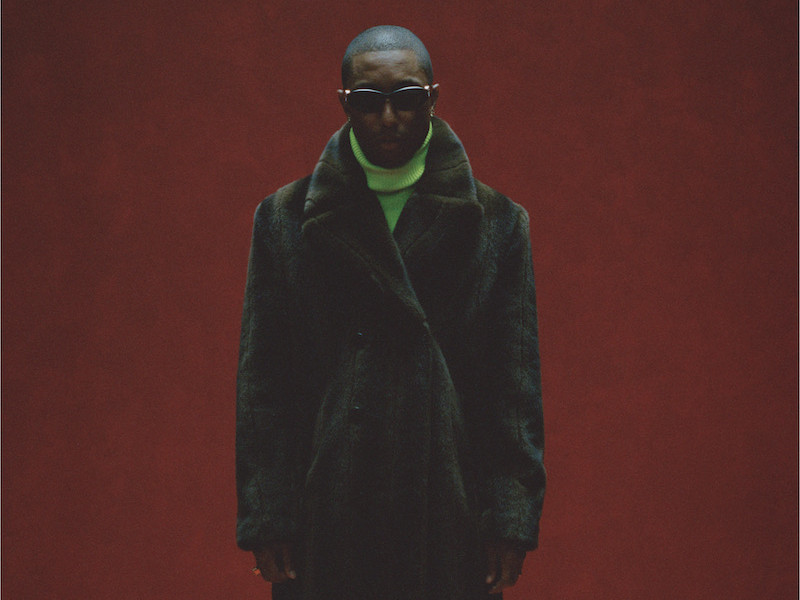

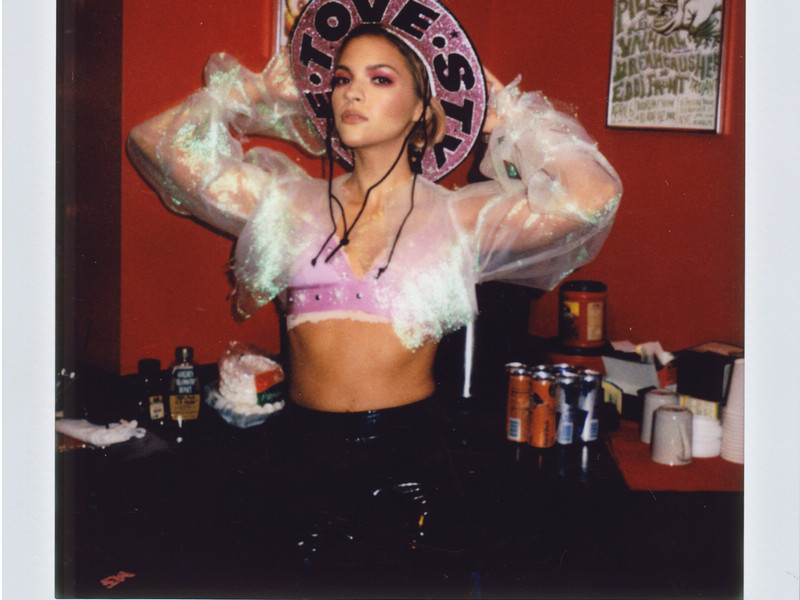

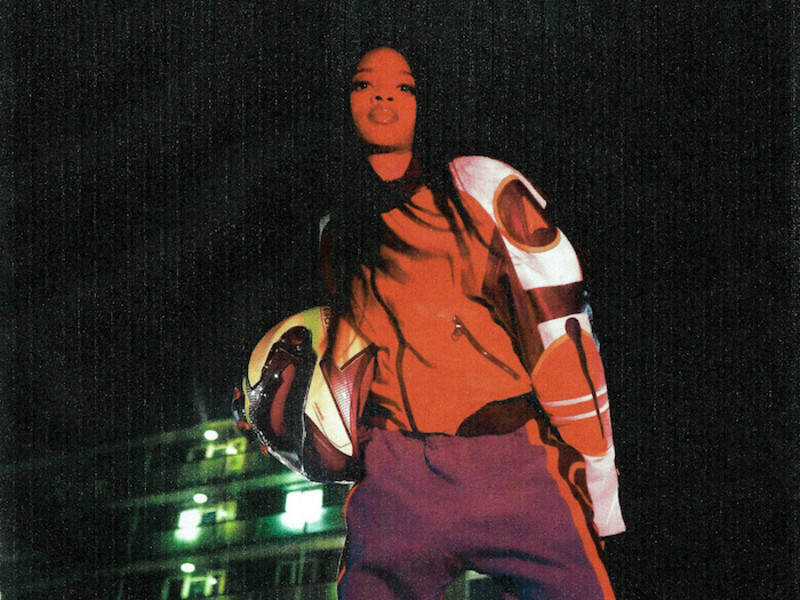

Although the band has received critical acclaim and praise for the recordings themselves, Chanel Beads' immersive performances are in a lane of their own, offering re-worked tracks that take on a whole new life and sound onstage with Shane’s spirited act alongside frequent collaborators Maya McGrory (on vocals & guitar), and Zachary Paul (violin). As of late, Chanel Beads has been on a tear, beating the ‘Dimes Square and Nolita-scene band’ allegations to a pulp with can’t-miss shows. Playing coast to coast and overseas, the band just played another round of shows in the UK before returning to New York ahead of the North American leg of their tour.

Fresh off his return flight from across the pond back to his home in Brooklyn, Shane sat down with office to unravel his unique creative process informed by two "F's" (feeling & function), the drawbacks of performing in caves, and the complicated, toxic relationship artists have with suits, algorithms and streaming platforms like Spotify.

Jack Kissane— My introduction to Chanel Beads was through word of mouth from a friend, which — in my opinion — is kind of the most organic way to discover music. I read that in a past interview, you threw a stray at the Spotify algorithm and the machine that it is. Can you expand on your thoughts about having your music found organically versus the algorithm just pushing it? And have you noticed a huge shift in who attends your shows since "EF" went nuclear?

Shane Lavers— Yeah, definitely. When we were in the uk, there were definitely some really sweet younger people that I think kind of got it from algorithmic stuff or whatever. But I don't know, I obviously have lots of thoughts and things to say [about Spotify], but yeah, you can't really control it, and sometimes I'm worried that the little balloon I was trying to blow up has already popped or something because I feel like my favorite experience with music is kind of more of a private one. And so it’s kind of sad to feel like people encounter it in a way that doesn't feel like it's just theirs. I'd rather have people listen to the music and feel like they're kind of alone with it in a sense. Or they can bring what they want and take what they want from it, or they have ownership over the music because all my favorite stuff, I feel like I have a personal relationship with it or that I have something to say to it and has something to say to me. So yeah, I mean, Spotify is so fucking stupid too. As a business model and everything. It's just brought an untold amount of rot into the music business world, but at the same time, it's so sick to be able to listen to whatever you want. And I guess the one positive thing I'll say about Spotify – but it's not unique to just Spotify – is that through related artists and stuff like that, there's just so much. And then seeing other people post public podcasts or playlists, you can do so much fun music discovery.

Yeah, I guess there are two sides to the coin with that, but I definitely feel you with the personal experience though, like the things I come across organically, just hit differently. Nothing beats randomly stumbling across a sick opener at a random show, because then you have that in-person experience and can attach that artist to a certain moment in time versus listening to an album and then a random song popping up after it on shuffle. Which is still chill, but it’s still fuck Spotify.

Yeah, I don't really know how I feel about algorithmic stuff because for XY reasons, Fuck Spotify, but I think I don't really have a problem with how you come across it so much as if it actually engages with you.

I feel like I get fed a lot of nonsense most of the time, but hey, I mean, we're in the AI era of society now.

Yeah, with your job you're probably more interested in music discovery than I am too. I actually don't really engage. I don't really need to use algorithmic or curatorial music stuff very much. I guess I'm not very conscious of how I'm encountering music these days.

Do you listen to a lot of music now? I mean, I talk to artists and a lot of them say that they're so invested in their own work that it kind of becomes all-consuming and listening to other music can get in the way of original creative thoughts. Do you ever find that to be the case, or are you just completely open to how you listen to music?

I'm pretty open. I've never been like, ‘Oh, I need to work on my album or sound so I need to hermetically seal myself off from influences.’ When I'm working on music, I never don't want to hear something because of the way It will affect the way I'm making music. Because my approach to a lot of the music that I make is based on a feeling. It's not really approaching it with a, ‘Oh, here's a vibe or a sound I want to create,’ so much as it’s more ‘Here's a feeling I want to convey.’ And so as much as anybody will try to rip something off, I won't make a song or finish it or want to put it out unless it's starting from an intellectual or emotional feeling of mine and feel that music is the route to convey it rather than the other way around.

I only ask that because I feel like a lot of the music you make feels self-referential vs. sounding like anything else that I've ever heard. For the past few months, your music has been the coolest stuff to put my friends onto because of how unique it feels. It’s just hard to put a label on it. I am sure you've seen articles trying to put a name to your sound.

Yeah, it's funny. I remember seeing this word when I was really young, and now it’s coming up for my music. Hypnogogic pop or something. So it's kind of funny. I always thought that was not a genre. I don't think of my music as dreamy at all or dreamlike or surreal. So it's kind of funny that people kind of attach those themes to it. My approach just feels kind of like making folk music or just making a folk song. But it's like we make it on the computer, and we don't really have a studio to go to, so it's just like however you can assemble it in kind of an impatient way. I collaborate a lot with Maya [McGrory] and Zach [Paul], and there is kind of this thing of like, ‘Hey, are you free today to help?’ Like I have an idea for maybe a string thing Zach can do, and if he's not free, I'm not going to sit on my thumbs, I'm just going to work on it myself. And then sometimes I'll be like, ‘I like it, this works.’ So with genre and stuff like that, it's just the making of the music to match a feeling. It's just a functional process. Like, I'm feeling this emotion and I want to work on it. That also relates to why I would never be like, ‘Oh, I'm not going to listen to music right now because I’m working on my own stuff.’ Because it's like there's no conscious effort to marry what I'm listening to, to what I'm working on. Because the thing that I'm working on is what I have in front of me. Like we just bought a cello. I dunno, just whatever's there, it's very functional and it's very problem solving in a way. To me it feels like a little unrelated to a certain genre.

Definitely, and you bringing up that functional point makes a lot of sense because I love how you marry synthetic and acoustic instruments together. And it especially comes out in your live show performances. I've seen some of the recorded live performances and at times the songs sound almost completely different than how they do on DSPs. Have you ever performed a song and thought, ‘damn, I wish we recorded it initially and published it that way?’

Yeah, I mean, the way we perform some of the songs kind of leads back to my point about functionality in that it's not really a choice of, ‘Oh, how do I make acoustic autotune music?’ It's just like, you can move quicker with autotune. I can focus on different things than I normally would if I didn't have the autotune on or something like that. And also, I don't use autotune all the time. I feel like people talk about a song thinking it has autotune when it doesn't.

Yeah, because you can sing with a pretty high register just by yourself, right?

With a microphone, you can sing quietly and higher than you can at a show. I feel like at a show, I'd much rather reach those notes by kind of screaming it or yelling it. Man, it's funny, I'm always self-conscious if we're just playing the songs too close to how they're recorded a little bit. But there's a bunch of music where I'm like, if I go back and listen to the recording, I'm like, ‘Oh, this is almost way more wimpy than I thought it was from the way that we've been playing it.’ And I'm kind of like, ‘Oh yeah, I wish I could have brought more intensity to stuff.’ But at the same time, maybe some artists just operate from what kind of music they want to make or something. And I always feel a little bit annoyed in that I feel very limited in what I can do musically in terms of what I feel motivated to finish. I feel like I don't really have enough decision making in my own music because of the functionality of it. It's like it works or it doesn't work to me. And so it just comes out how it comes out. And it's like if I want to make an intense song, I have no idea if it'll come out intense or not. Same thing if I want to make a high energy song or not. I can't really tell if I'm going to end up coming up with one at the end of the night or whatever. Sometimes I start with a high intensity song, but then it turns into this mellower or stranger thing, or vice versa where it's like, I'm trying to stretch something out into this more ambient thing, and then it just comes out totally different. Sometimes it feels like decisions weren't made along the way, even though technically you are making them. It’s more just deciding if something is working or not. It's like if you're tinkering with something and you don't look up and all of a sudden hours have passed and it's totally different from what you thought it was intially. You didn't really feel like you made what it’s in front of you it kind of just took its own shape that way.

Yeah, sometimes it feels like things just take their own course. When I'm writing, sometimes I go in with a certain perspective and things just change along the way, and it becomes something entirely different.

Or when you're talking out loud about something that you don't know how you feel about it until you say it.

Circling back to the live shows, I had heard from the same friend who put me on to your music, that you had done a show in a train tunnel?

Yeah.

Is that the craziest place that you've performed and is there a good story to that?

I mean, we didn't organize the show, so I kind of feel bad because people are like, ‘Oh, Chanel Beads played in a train tunnel,’ But our friends organized the show, and they played too. So I feel like I have to give credit to GodCaster and YHWH Nailgun, the ones who put the show on. We just played first, and yeah, they're the ones who did all the heavy lifting. When the cops came, they arrested one of the Godcaster guys' brother, and they tried to find them. So yeah, Godcaster found this place and organized this awesome show in a train tunnel.

Where was this? In New York?

Yeah, it was in Brooklyn. The spot kind of got blown up because I think we thought we were being clever and playing in a place that was inobtrusive. They talked to the guy living really close to it a week prior, and they gave him some money and stuff, but I guess the spot just got kind of blew up and there was a show there every day for six days. The cops came every day, and a local bar was like, ‘You guys, please stop doing shows here.’ And I was like, ‘Yeah, fair enough. This is actually pretty disruptive.’ But yeah, I dunno, that didn't feel like the craziest place. We've done some weird little runs where it's like we have no idea what the space is until we get there. And then also, what feels crazy to you isn't as crazy to other people where it's like, we played a little loft in France where you could barely see in front of your hand because of all the cigarette smoke and shit. That's new to me, and that was weird. Or we played this place in London where you kind of feel like you're in a grain silo and there's no stage. On tour you're exhausted, and there's different drugs in different cities and stuff, so it's like, yeah, I dunno it's really hard to say what the weirdest one is. There's a venue in Seattle that's like an old pharmacy and they just kept it up. Like, it looks like a fully functioning pharmacy in there…

Y’all were posted up and performing in a drugstore's aisle? That's crazy.

Yeah, yeah. In the lotion aisle! Honestly, if I had to give you one answer on the craziest place we’ve played, my answer would be boring. We played a college where it was like literally during a study hall. Everyone was on their computer with headphones. And I was like, ‘Why the fuck are we here playing this?’ But the colleges have money, so it helps fund the tour. We played the worst show to people who didn’t care about us, it's Tuesday night, and half the people have headphones on and they're just on their computer. To me, that's the craziest show because it's like, what’s the point? Yeah, also with the train tunnel thing, I always call it a cave, even though it's not a cave. It was literally a train track tunnel.

Hey man, this is a written interview, we could call it a cave in the final edit, honestly.

Yeah, yeah. It's up for dispute if it's a cave or a tunnel!

Another thing I think is really cool about your live shows is the intimate aspect that you guys put forth in each show. I think I read somewhere that you would much prefer playing on the same level versus being on a stage above the audience. Is there a certain rationale behind that, or is it just based off preference?

Well, I think, I actually get asked this a lot and I'm kind of trying not to talk about stage stuff in interviews a little bit, because you just play where you're lucky to play. And if people pay to see it, I don't want to act like, ‘Oh, I don't fucking like this stage.’ It's like, if you paid 30 bucks, I'm going to try to give a good show for it. But yeah, I just think people try to pigeonhole us into this. I'm surprised how stubborn people are about what they think live music should be. And so when we play bigger stages, everyone's like, ‘Where's the drum kit?’ And all this shit. And I'm like, ‘I don't know.’ When I think about my most impactful live music experiences, a lot of it's like DJ stuff. I am pretty compelled with the act of playing recorded music in a live setting without being a sample guy or something like that. Because honestly, I don't really feel like a sampler. I don't sample other people, I just assemble it in a way that you would write or do notation or something. So I think there's something really compelling about playing recorded music and seeing how it's interacting with the space, crowd, the night, and the event [as a whole] and then how your emotional response to it can change too when you put all those things together. And so performing to that with recorded music is still really compelling to me. So it's more annoying and there's more expectations that I don't agree with in these bigger stages or bigger arenas, but also maybe a lot of that's projection. I don't know. Yeah, I don't want to imagine an enemy and just be like shadowboxing in an arena because I think someone has a problem with it.

Your Day Will Come is genuinely one of my favorite releases of this year. You put forth these crazy collages of the acoustic with the synthetic, and then you have random sound bites, and ambient textures, and then on top of all of that, you have this violin being such an integral, almost backbone to the project itself, which is just really a cool touch. Was there a certain moment in time or a specific track, the sound all clicked for you? And you're like, ‘Oh yeah, this is my sound.’ Or do you feel like that hasn't happened yet?

Well, I've been making music for so long, and then I just took a big huge break between putting stuff out because I think I was struggling with not wanting to make a whole ambient record, or a whole rock record. I was kind of feeling overwhelmed by distinctions and structures of stuff. And so I think a few years ago I just felt pretty liberated of no longer thinking about them. It's just music, it's just recordings, and you treat any kind of sound source the same and it just becomes functional. And so it's like the reason that I use a lot of synthetic MIDI string sounds on the record is because I think it almost feels like it doesn't get in the way of things. I mean obviously [synthetic strings] have a ton of preexisting connotations in your brain, but if I start from there, I'm like, ‘Well, it's almost like anti sound design music’ or something like that because it's such a ubiquitous signifier of a sound you've already heard. And it's not like an acoustic sound that I'm producing myself. So I think it kind of feels like, ‘Okay, now that that's out of the way, now I can focus on what kind of thought or feeling that I want to explore at that point.’ It’s like finding yourself in an already existing thing.

Another thing that really stands out to me with Chanel Beads is the aesthetics and the visuals that you use for all the releases with the album covers, music videos, or even the visualizers. It is all really either incredibly nostalgic or super eerie, almost as if you collected them all from an untouched storage attic where there’s an 18th-century painting right next to a bunch of dusty VHS tapes. How'd you come up with this creative direction? Is that led by the music or kind of vice versa?

It's definitely not led by the music. It's kind of, just my taste, *laughs* I guess. Yeah I feel really critical of visual art styles because I'm almost salty that some stuff that I really like, that I feel like maybe I was doing at the time, is just so easy to replicate. So by the time you're like, ‘Oh, that's cool,’ everyone can just do it. And if you put, I don't know, the iPhone Flash 0.5 camera thing, that's just what everything looks like now. So it's cool because it's like democratized. But yea I don’t know, it's funny, a lot of people seem to see it as this big, unified...

... "Unified Thought?"

Yeah. [Laughs] This unified art thing that I'm doing, doesn’t really have a ton of intention behind it, honestly. Maybe I'm failing at what I'm trying to do because I’m not trying to have the visuals get in the way of the music, but maybe they're calling too much attention to themselves and maybe I have to rethink the approach. But I think I'm always worried that the music is too nostalgic because to me it's not, it's usually about reckoning with an issue that I have in the moment. So it's not really nostalgic, it's just maybe about the cumulation of a feeling or emotion. So I think because there's that kind of, ‘Where have we been? Where are we going?’ thing that reads like nostalgia to people. Like [Your Day Will Come's cover art] is just a painting that I liked, but I really liked this one little section of it. I just thought it was compelling. I guess the artwork was inspired by the music in a sense of, I think it's interesting to kind of try to have something feel like it extends beyond the frame, but also have the piece of it represent the whole, but also at the same time comments on the whole in a way that maybe misrepresents the whole. So I think it's by just focusing on this one girl's expression, you're missing the huge fire, which I think is actually the center of the painting. The painting is called Midsummer Eve Bonfire on Skagen Beach. I feel like that kind of mirrors, I guess some of the approach to the sentiment of lyrics and then the sentiment of the approach to constructing the sound. As much as I'm like, nothing's thought out, I think it's an approach that I like when I'm not thinking about the approach itself, but rather when my music just works its way into its own thing.