The warehouse, home to Sheerly Touch-Ya and Shisanwu LLC, are both headed by artist and Lunch Hour member Serena Chang—the former being her family’s first American enterprise upon migrating from Taiwan, the latter being her sculpture fabrication studio. On May 18th, within the context of these entities — charged by layered histories of artistic labor, material culture, fashion commerce, migration, and manufacturing technology — Means of Production opened the Sheerly Touch-Ya warehouse to the public for the first time in its history. The night of performances from a slew of artists, activists, and creatives was just the beginning of an ambitious eight-week exhibition run, which included an art workers’ town hall on June 8th, and an upcoming film program Out of Circulation organized by third Lunch Hour member Lily Jue Sheng on June 29th.

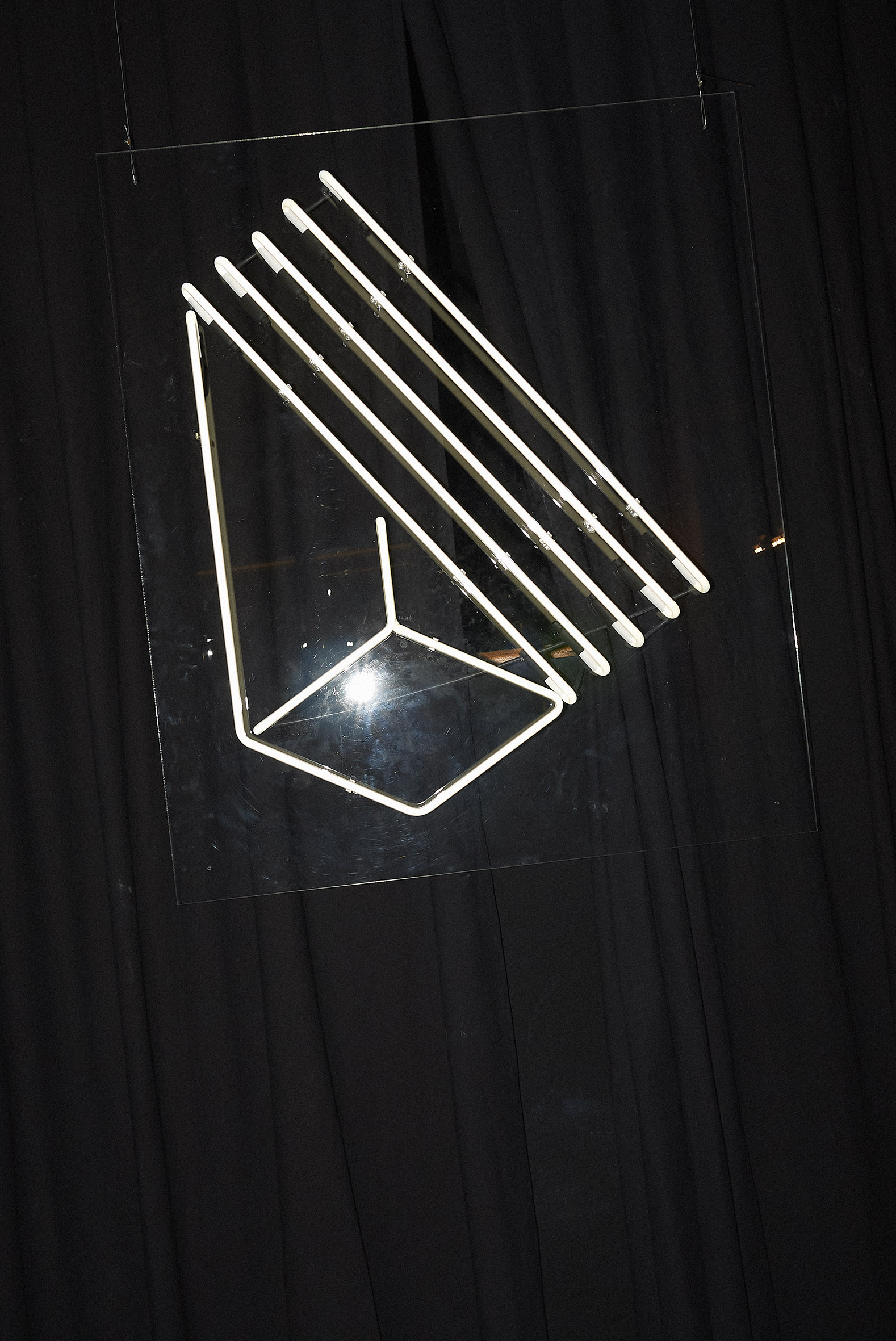

Behind an industrial metal door with vinyl lettering “SHIS NWU” (the “A” has fallen off), I slip into the Sheerly Touch-Ya warehouse on opening day, the entryway opening into a tiered industrial space full of palettes, plywood, pipes, and metal scaffolding. A thrilling slippage between what is an art object and what is warehouse environs sets in: is an open bag of sweeping compound a work of art? Maybe. The open book on a worktable, or the spectacles on a styrofoam block, with twigs for arms? Probably. Artworks tucked between boxes of hosiery, left unannounced on the concrete floor, or strung up on the rungs of industrial pallet shelves offer an invigorating disorientation.

Works in the show are not clearly demarcated from warehouse supplies — echoing the thesis of the project, which brings focus to the hazy lines between precarious and acknowledged, waged and unwaged labor. To this point, Linh explains, “Our subversive decision to present artworks in a warehouse, rather than a white cube or museum, challenges conventional notions of art and authority. It raises questions about what constitutes art and who has the power to define or value it. This setting infused our project with humor, playfulness, and a sense of freedom — elements that artists and art workers rarely experience today.”

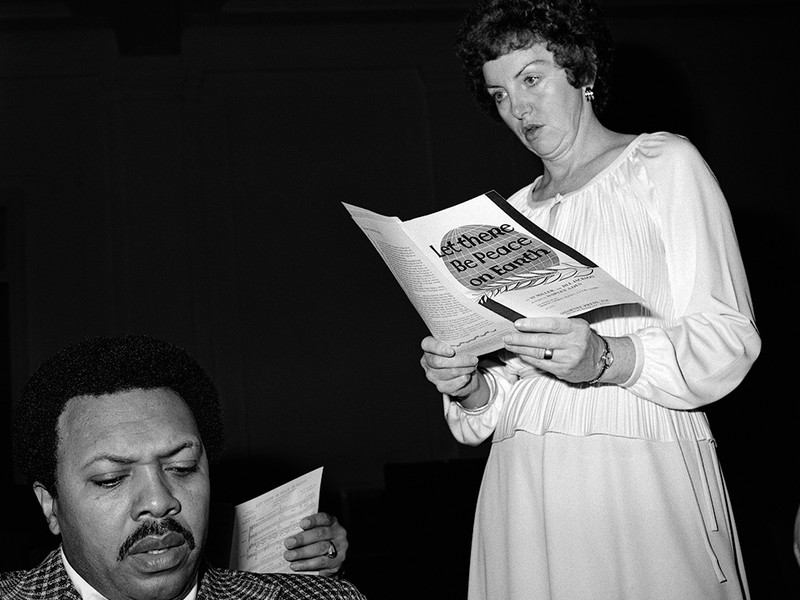

Around 5pm, a group of performance artists begin to wander the entry room with intention, winding small handheld radios while an audience gathers. Performer and choreographer Anh Vo’s Common Fetish calls on a wide list of citations including “Vietnamese possession rituals, Communist propaganda, Nicki Minaj, Jacques Derrida, Christina Sharpe, Thich Nhat Hanh,” among others. At times evocative of a Buddhist chant, a Catholic prayer, a rodeo speech, or a pledge of allegiance, the performers Anh Vo, Kristel Baldoz, Kris Lee, and Nile Harris engage in a call and response. “I am a hole for you to penetrate,” they speak in unison while transitioning from floating independently to a ritual circle. As the procession of performers and audience members trickle deeper into the warehouse, down a dark aisle of boxed stockings, Ethan Philbrick plays the cello in deep bellows and sharp picks. Some clothes are removed and the script becomes darker. Movements become less rhythmic, more rattling, more haunted. The push and pull of performers and bodies, in both possession and dispossession, signals to the interpenetrating nature of the sexual, the spiritual, the psychic, the political, and the somatic all at once.