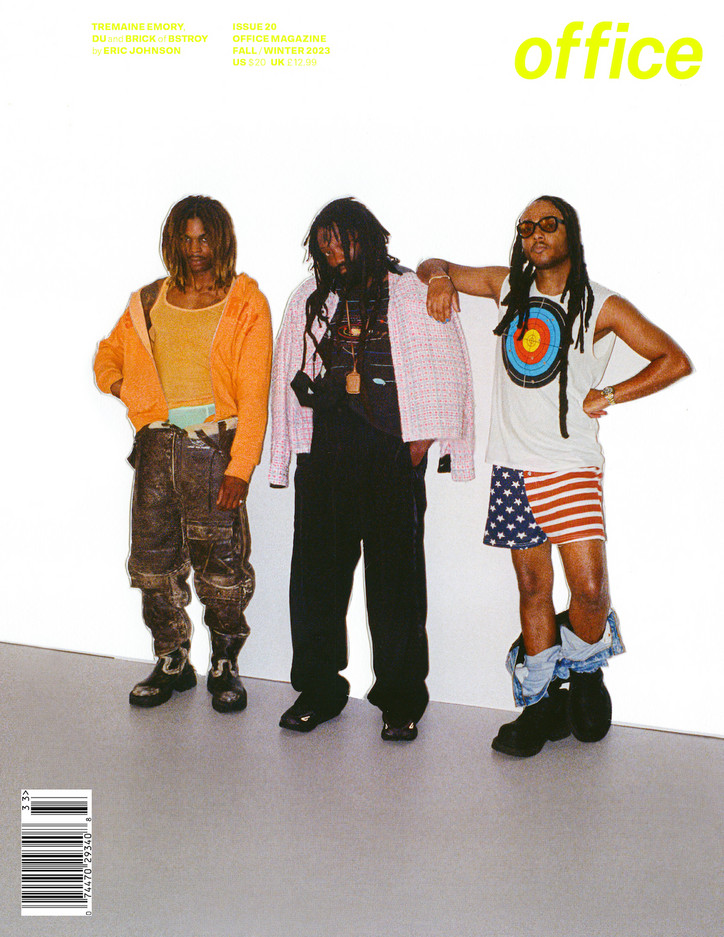

“The Black life is still so much about survival,” says Du. “Most haven't had the opportunity to specialize and live off art in a professional way. I will say, V did an excellent job of employing people of color, and equating their experience to an artistic education, making sure they’re valued even if they don’t have a certificate from a school.”

He is, of course, referring to the late Virgil Abloh, founder of the label Off-White and the first Black creative director of Louis Vuitton. An early supporter of Denim Tears, No Vacancy Inn, and Bstroy, Virgil was a beacon of professional and personal guidance and inspiration. The three men bring up “V” affectionately and often — citing his work ethic, his compassion, his humility, and his strategic wisdom.

Tremaine learned of Abloh’s passing from a New York Times push notification the same week he received the offer to become creative director at Supreme. “I landed in Miami and had 200 messages, everyone saying ‘sorry for your loss.’ The only pop-up I have on my phone is the Times, and then it popped up, that Virgil passed,” he describes.

Brick recalls how he delivered the news to Du, who was visiting his family in Atlanta: “I remember you pulled the car over on FaceTime, the way you just said, no.”

“I almost crashed the car,” Du says. “You don’t ever think your superhero is gonna die. From that day I left Atlanta and I was like, ‘I'm not taking no breaks.’ Because V was somebody that, you call him at any moment, he’s picking up the phone for you, but he's knee-deep in five things, and he'll show you. We only get 24 hours in a day, but it seemed like he had more.”

That refrain — I’m not taking no breaks — gives me pause. When I ask about work-life balance, the three exchange sly smiles. “When I talk about this tribe and this mission that we’re on,” Du says, “It’s really our whole life. I think that’s the only reason why we see anything back from it.”

Tremaine references Frantz Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks, in which the French psychoanalyst and philosopher expands on the “double consciousness” Black people experience as a result of viewing themselves through the eyes of a racist white society. “That shit is ingrained in everything, and you have to work against it,” Tremaine explains. He tells me about his uncle, who was never once late to work in 40 years at the same job. “He knew he couldn’t be late because he’s Black. We can’t take six weeks off in the summer holidays like they do in Europe and turn off our emails for August. That shit doesn’t work for us, man.”

“It’s funny, people say to me, ‘Do you think you got the aneurysm because you work so hard?’” Tremaine continues. “And for one, no I didn’t — they’re hereditary. But even if it was the cause, I wouldn’t change a fucking thing because I wouldn’t have been able to make it this far if I didn’t work how I worked. Being mediocre isn’t allowed for Black people, and part of that is working all the time. It’s unfortunate, but that’s the truth.”

The lower aorta aneurysm Tremaine is referring to occurred in October 2022, just 8 months after he took the helm at Supreme. It left him hospitalized until the end of the year and forced him to slow his pace for perhaps the first time since his career began, but Tremaine’s idea of deceleration looks a little different. Even as he was still hospitalized and engaged in physical therapy to regain his ability to walk, his “Dior Tears'' capsule in collaboration with Dior Mens was unveiled in early December. He credits his survival to the support of his friends and loved ones. “What saved me was the love of my fiancée Andee, of Acyde, Anthony [Specter], Cactus [Plant Flea Market founder Cynthia Lu] flying in from Hawaii twice, Brick and Du bringing me books.”

“I remember one time I had to stand up for five minutes without a walker, which was really hard,” Tremaine tells me. “And then Brick took the time to make me do like eight minutes, or 10 minutes instead of five minutes. All those things in my life where someone has pushed me and seen what I can do — I didn't know I could stand for eight minutes, but Brick felt that. That’s the best kind of help, when people believe in you and push you to do what you don't know you can do.”

Brick looks almost surprised. “Me pushing Tremaine — at that moment when I did that, I just saw something that he didn't see for himself,” he says. “At many times, Du was that person to me. The inner workings of those relationships are so interesting.”

“But also, if you're friends with a superhero and you are present during their recovery, you're gonna push them a little bit because the world still needs to be saved,” Du adds. “I feel like the job is that serious for us.”

The hyperbole may be extreme, but its extremity seems more warranted when you consider the dearth of the three men’s comparable living contemporaries. According to a 2020 report from Women’s Wear Daily, Black members only make up 4% of the Council of Fashion Designers of America. Tremaine tells me about how he was recently mistaken for a homeless person in his TriBeCa neighborhood, and still gets racially profiled in public spaces—including at a bakery the day his position at Supreme was announced. The dissonance between the discrimination and the highly visible success these designers have experienced is only exacerbated by the isolation they experience in their field.

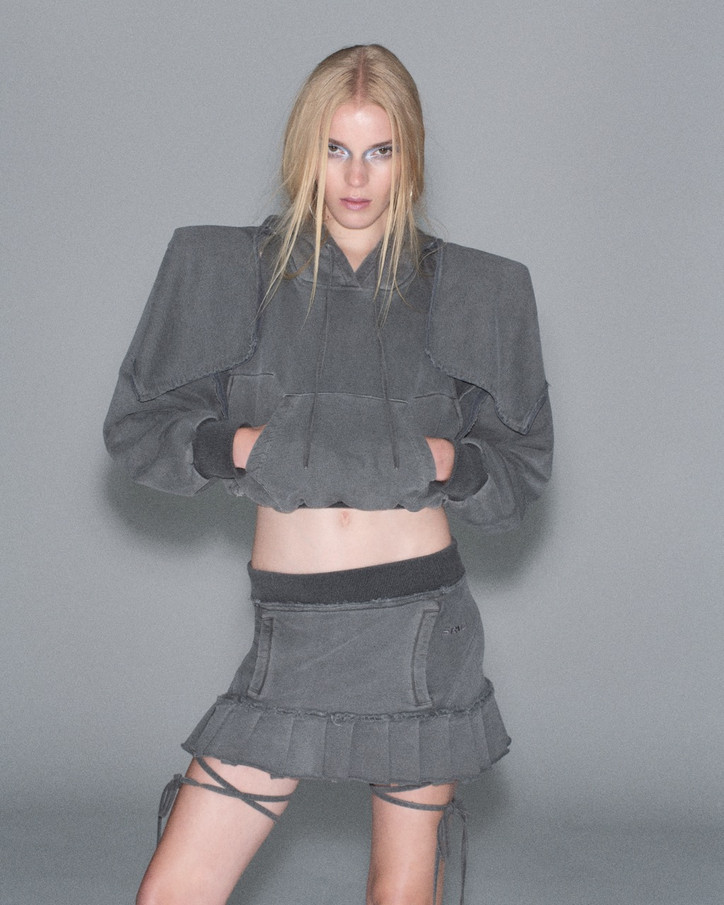

“When you break through as a Black person, you're usually alone,” Tremaine says. That’s precisely why the inclusion of his designs among a collection of established legacy designers in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, alongside those of Bstroy, Hood By Air (Shayne Oliver), Fear of God (Jerry Lorenzo), Pyer Moss (Kerby Jean Raymond), Virgil Abloh, and Heron Preston, was so meaningful. The exhibition In America: A Lexicon of Fashion was curated by Andrew Bolton for the Met’s Anna Wintour Costume Center in September 2021 and added over 70 new ensembles in March 2022.

Tremaine confesses that he became emotional when the collection was unveiled. “I was literally waterworks crying when I seen it, and it wasn’t the validation of the Met solely. It was the fact that I was in there with my contemporaries,” he explains. “Even the designs included that I don’t fuck with, I still respected it. And it didn't say shit about ‘streetwear,’ it said exactly what the cotton wreath means, exactly what that double-headed hoodie means, and what that pan-African flag means.”

The diversity of that collection came as a surprise to some, considering the Met’s costume holdings are overwhelmingly white. As New York Times fashion critic Vanessa Friedman pointed out, the Met has “a pointed, fairly chunky political agenda of its own that has to do with redressing historical racism.” But irrespective of motive, the institutional canonization of Black designers as part of American fashion history is politically significant and in many ways unprecedented, especially for those who were previously relegated to the often dismissive label of “streetwear.”

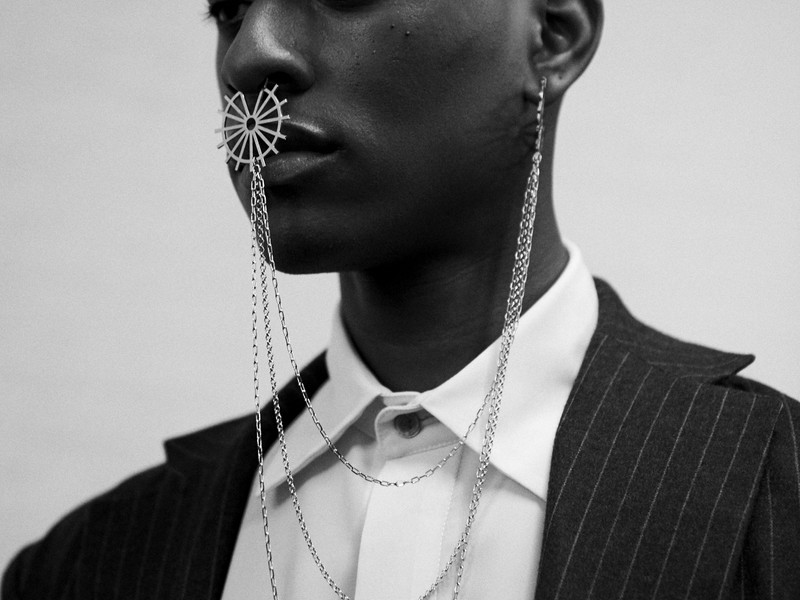

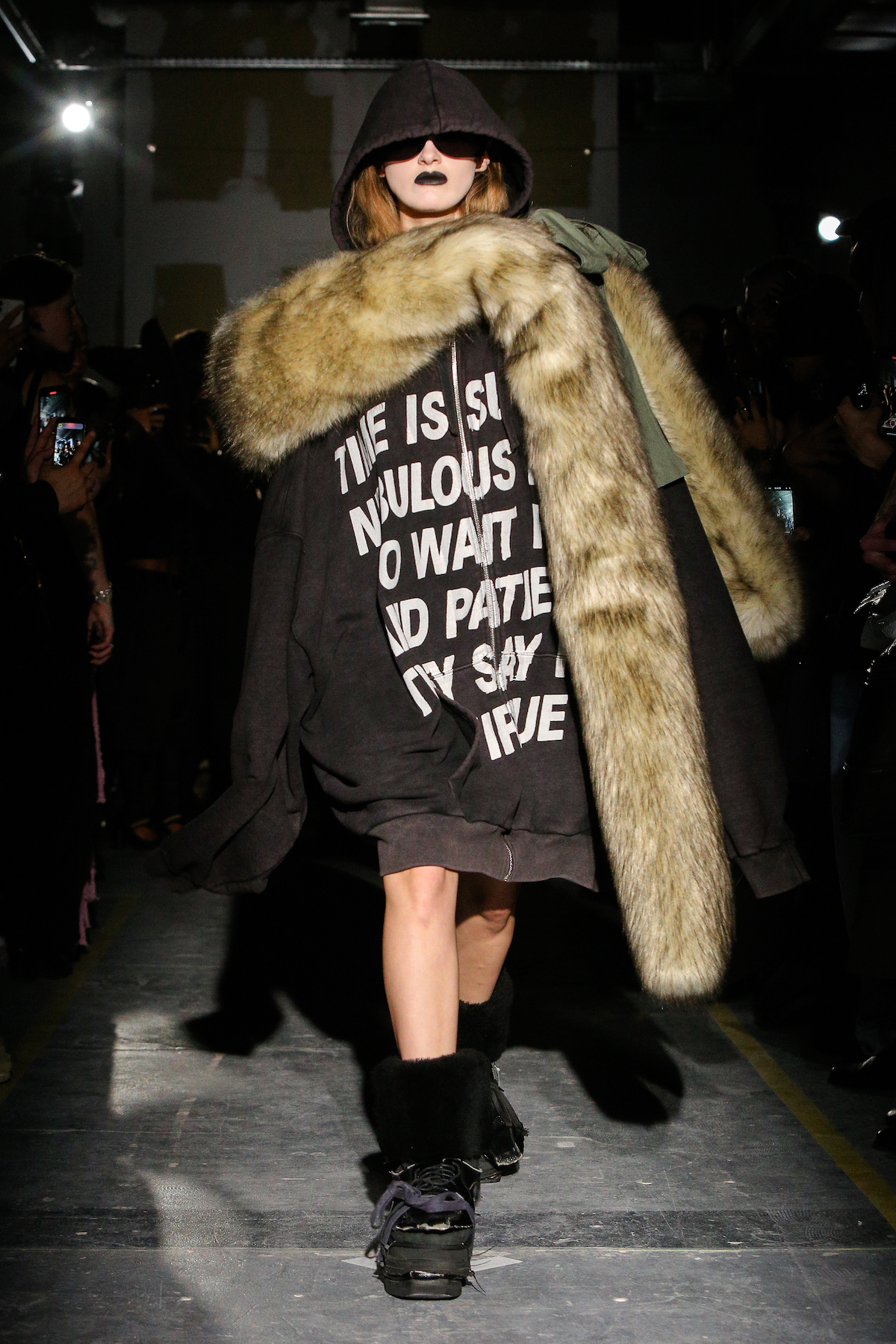

Streetwear is largely thought to have originated in the New York City hip hop scene of the 1970s and 1980s, describing a style of dress that features comfortable, casual, and often looser garments like t-shirts, hoodies, workwear, sportswear, and sneakers with influences from Japanese street fashion, punk and skater subcultures, and status-symbol designer brands. The style was proliferated by rappers and musicians in the 1990s and early 2000s, and experienced a massive boom in popularity in the 2010s, heralded by many of the designers Tremaine mentions who were featured in the Met alongside him.

The 2010s revival brought about the cultural phenomenon of the “hypebeast.” The term, dripping with mockery, refers to an archetype of consumer that obsesses over the latest, most hyped streetwear products and seeks to flaunt rare and expensive garments and sneakers as status symbols. The hypebeast has become increasingly unpopular over time, drawing the derision of both the more pretentious and purportedly chic fashion class — to whom hypebeast culture is gauche, unsophisticated, firmly adolescent, and implicitly, too Black — and the normie crowd, to whom the hypebeast is materialistic, shallow, and tacky.

With streetwear’s spike in popularity came a conundrum of classification. Fashion gatekeepers were and often still are adamant on its distinction from high fashion, but designers like Virgil – who began his career screen printing t-shirts – increasingly blurred that distinction, designing haute couture at the time of his death. I am reminded of the history of another rule-breaking genre pioneered by Black people within a larger medium: jazz, which was coincidentally also one of the inspirations behind the Dior Tears capsule. Despite being one of the earliest original American art forms, jazz was punished for its amorphousness and condemned as a “primitive” and “immoral” form of music for decades before its eventual acceptance. But unlike jazz, streetwear’s title has yet to transcend its scarlet letter, and still carries a host of connotations. The insistent use of the term to describe designers that have long expanded beyond it often feels like a pointedly enforced division.

“I feel when someone says I'm a streetwear designer, you might as well be calling me a n*****,” Tremaine says. “Hard r.” Brick and Du nod in agreement. “I’m not knocking anyone who appreciates the term. But for me, anything that’s separation is derogatory. I'm not into the separation of anything when it comes to the arts.”

“Like, don't play with me. It's a matter of respect,” Brick adds. “For me personally, until we can get a textbook definition of what ‘streetwear’ is, I would prefer that we not be labeled as that. We're not sold in DTLR where we bought a lot of our shoes as a kid in the middle of the mall.”

“The thing is like, what makes it ‘street’?” Du asks. “Because ready-to-wear clothes are literally worn on the street. So what makes those streets different than the streets where people wear ‘streetwear?’”

“It’s all cement,” Brick muses.

“It’s a code word,” Du continues. “And it’s so obvious to us that it’s offensive.”

Tremaine references Fendi and Dior artistic director and longtime friend and collaborator Kim Jones, who told HighSnobiety in 2018 that he felt the term “streetwear” had outlived its descriptive use. “I currently design ready-to-wear and sportswear for men, and accessories,” Tremaine says. “That’s it. So I just wanna be called a fucking fashion designer.” I suggest another parallel: the former Grammy category of “Best Urban Contemporary Album” — once declared a “politically correct way to say the n-word” by Tyler, the Creator — which was heavily criticized for its generalization of work by Black musicians until it was renamed in 2020.

“What the fuck is that!?” Brick says. “It’s like ‘streetwear’. What does that mean besides, ‘Black, but we don’t want to say that.’”

“It's called segregation, and it was outlawed,” Du says, laughing.