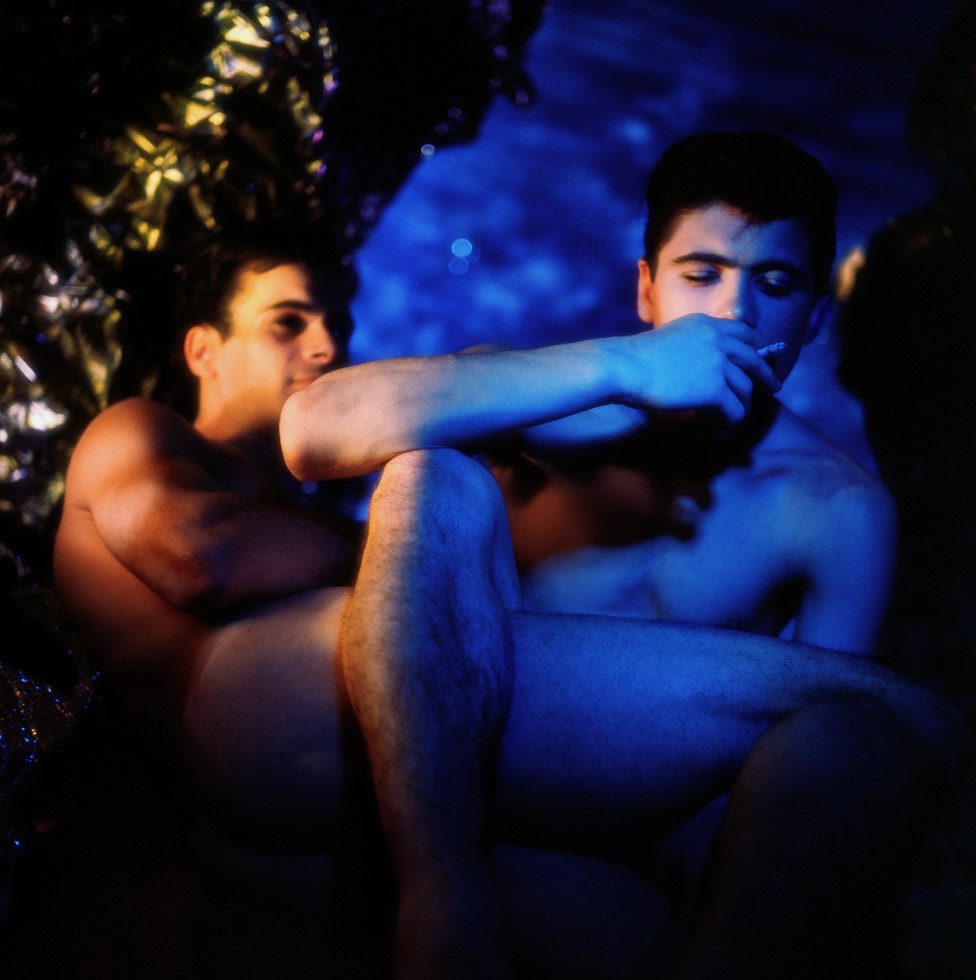

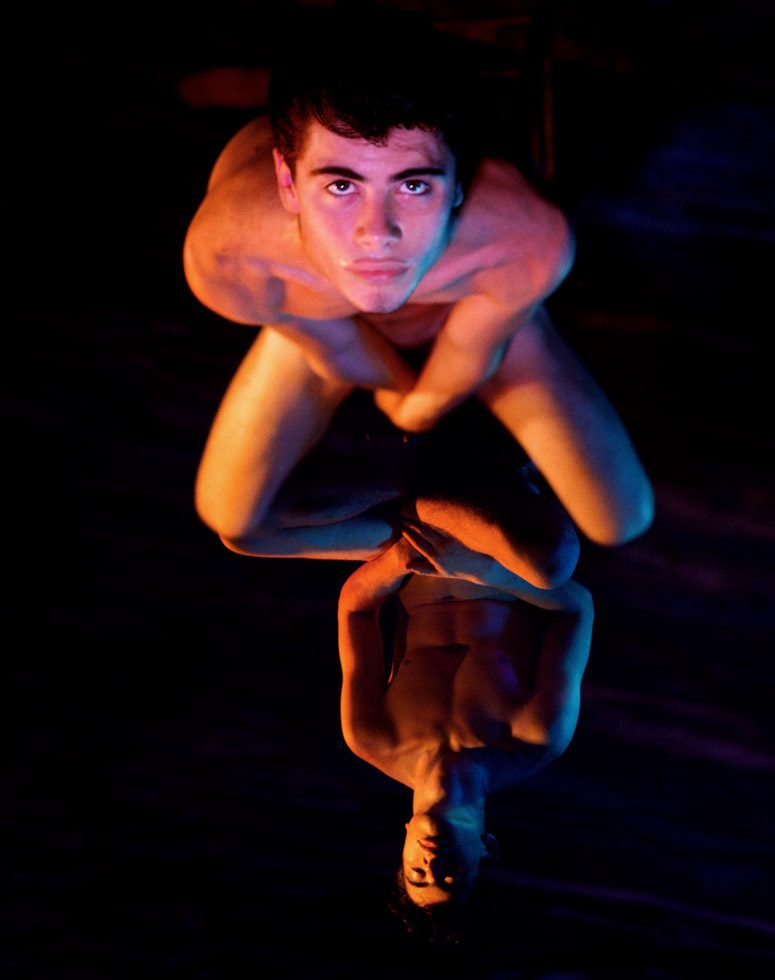

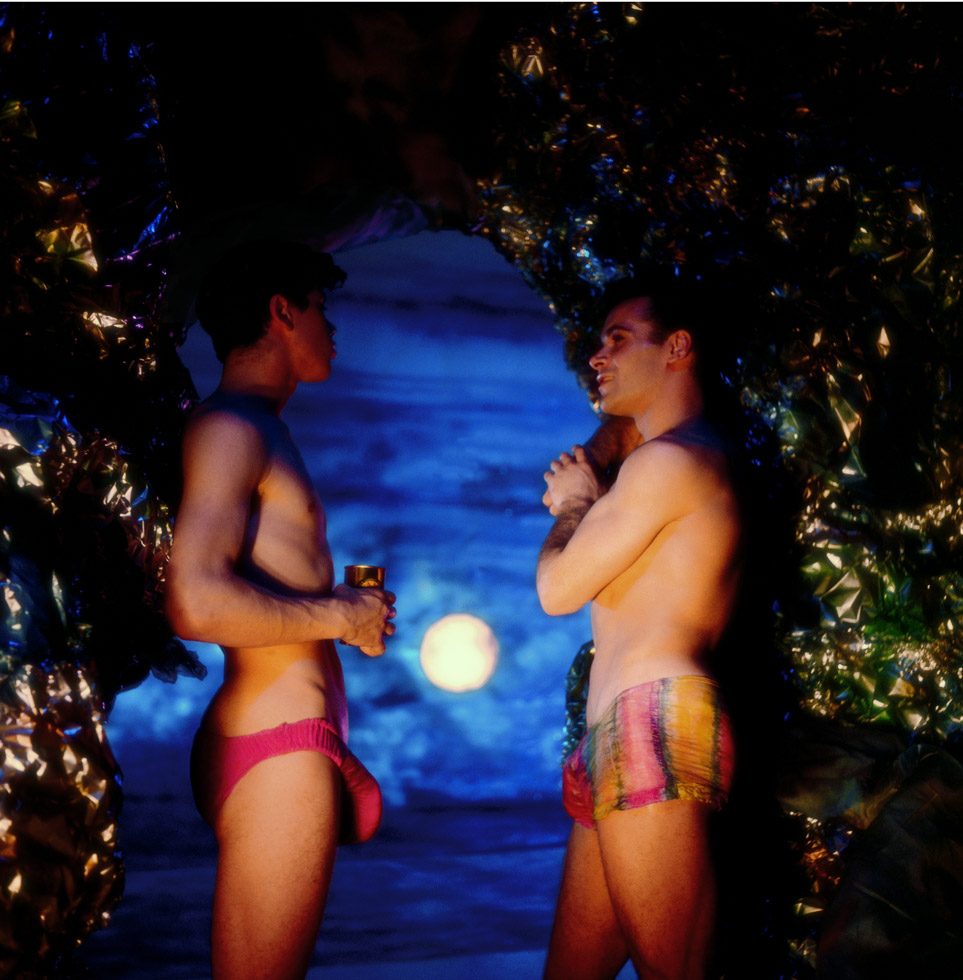

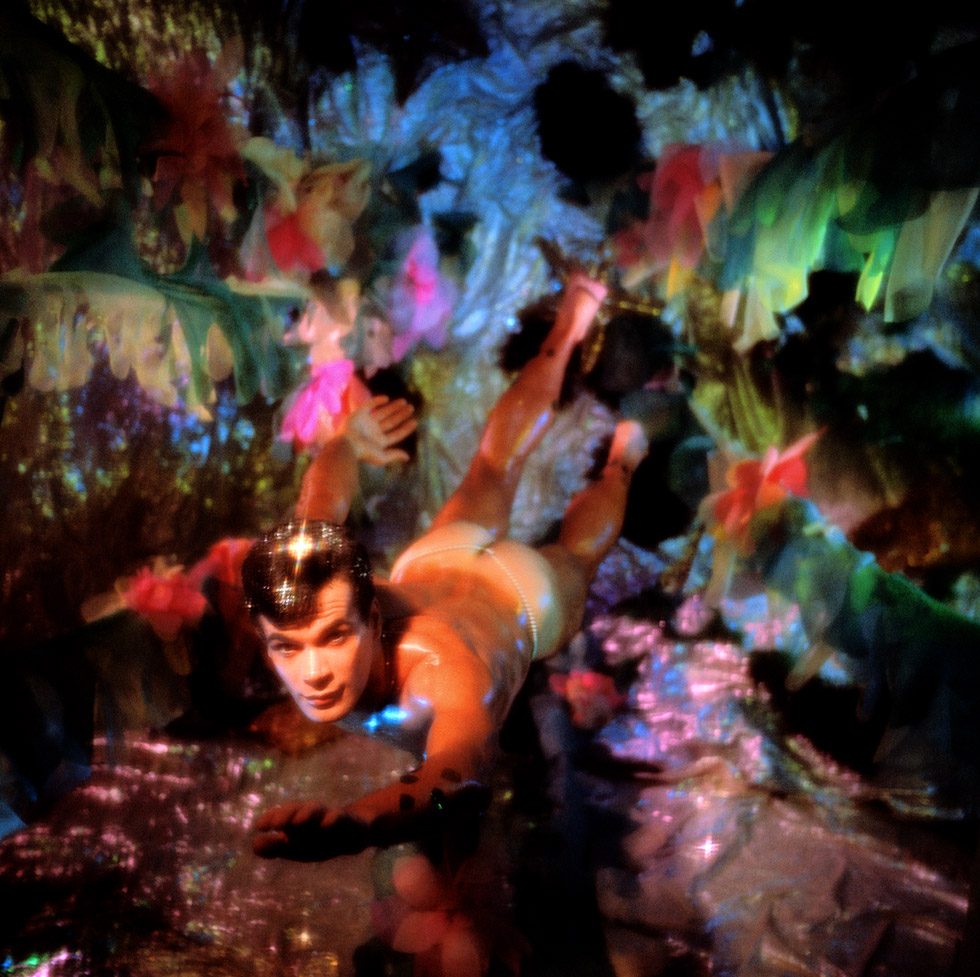

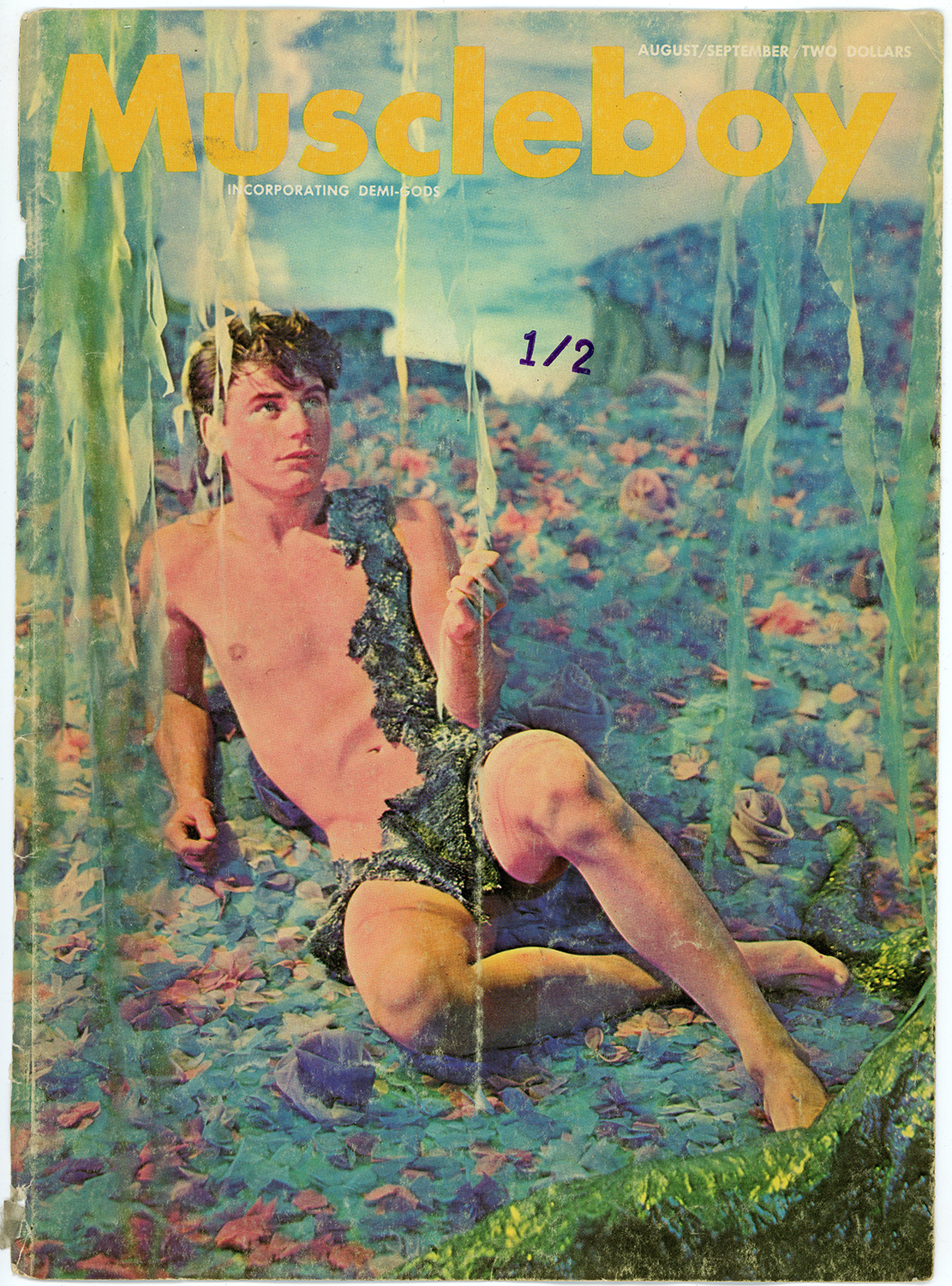

The restraint seems to have been one that Bidgood thrived on, dabbling as he did in the worlds of drag, hustling, and pornography; elements from these not-so-different realms combine to form a surprisingly tasteful (albeit titillating) body of work.

Such euphemistic magazines as those Bidgood contributed to aren’t so antiquated, actually — in the periodical section of Wal-mart some years ago, I stumbled upon and ended up amassing a small collection of a now out-of-print magazine called “Exercise For Men Only” that was essentially a modern equivalent of “Muscleboy.” It didn’t contain anything nearly as fanciful as Bidgood’s dreamlike layouts, but comparing the two is essentially a study in the evolution of the self-perception of gay men. Bidgood’s fuchsia wonderland bathed in glitter and gold is a world apart from the straightforward beefcakes “demonstrating” workout routines in “Exercise For Men Only.” Somehow, in a time that was ostensibly more repressive toward homosexuality, the expressive joy of the 60s seems to have been at a majestic zenith, the self-perception of queerness, at least in Bidgood's case, fully embracing prettiness, daintiness, fairy-ness, which, if we are to use "Exercise For Men Only" as example, seems to have been siphoned out of the gay community in the past 50 years in favor of machismo.

Whether it's machismo or effeminate eleganza, however, what is at play is the power of camp — the over-the-top bliss in corny extravagance, the unashamed sentimentality connected to an unreasonably idyllic state of being that makes the imagery at once cringe- and sigh-worthy. James Bidgood’s work is the femme answer to Tom of Finland, the softer side of the same coin. Both are camp at its absolute best, where it crosses into the lofty realm of art. Both art and camp contain a similar loftiness: the embodiment of an ideal at its most extreme, taken to heights previously unimaginable.