Cuts

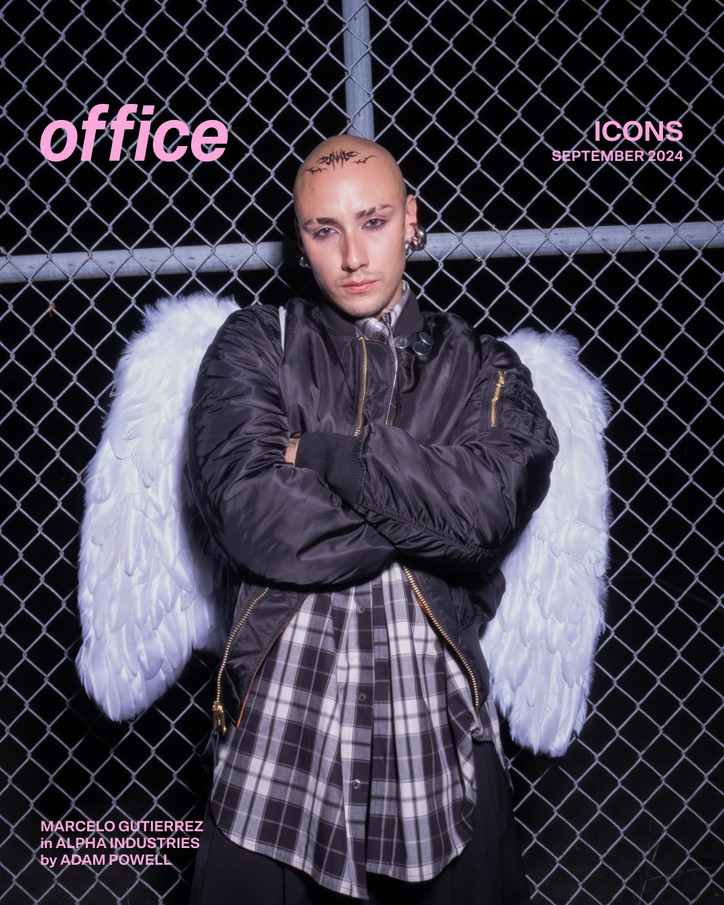

office called the photographer to chat about chronicling the punk and new wave moments, and his forthcoming film, No Ifs or Buts.

Could you give me a little bit of background about Cuts? Why did you start taking photographs there?

Cuts was started in 1978 by a guy called James Lebon. We became friends in 1980, and I sort of joined him then. It started in Kensington Market. Back in the ’70s and ‘80s, Kensington Market was youth cultural punk rock new romantic. Then we moved up the road to Kensington, where we had a salon and an art gallery. Then we opened the barber shop in Soho at the same time. Then the Kensington shop closed and it was just the barber shop, then then we opened a bigger barber shop. But women used to come as well. It was for alternative hairdressers—it was a lot more street. I suppose the salon was a bit like the old village square where people used to pass through on a daily basis. If they weren’t getting their haircut, they’d just come in and say hi, meet other people and be chatting. It was like a focal point. We had all sorts of clients from artists to musicians, and a lot of our favorite pop stars over the years.

Like who?

My favorite was David Bowie. Also, the lead singer of Duran Duran, Simon Le Bon. Boy George. Keith from Prodigy. Who else? Fashion designers like Alexander McQueen, Jean Paul Gaultier. We used to get members from the band The Pretenders.

.

There are so many popular hairstyles that really started with British punk. Which were most popular amongst the people you photographed?

There was the Buddha and the Fin. You know the haircut where it was like a shark’s fin on top of the head? We came up with that. The Buddha was really short, really cropped at the front and the sides and the back, then lifted up at the crown.

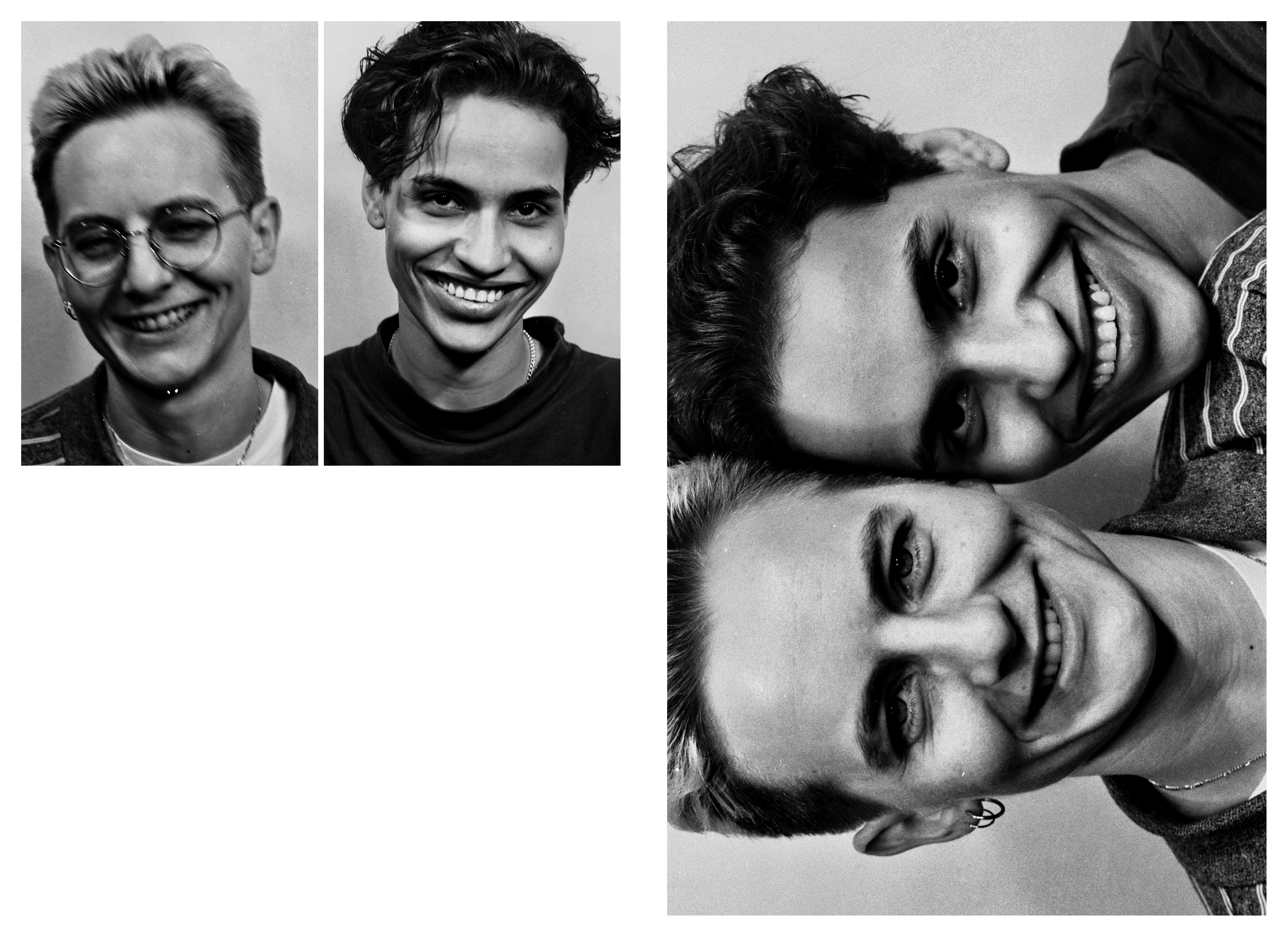

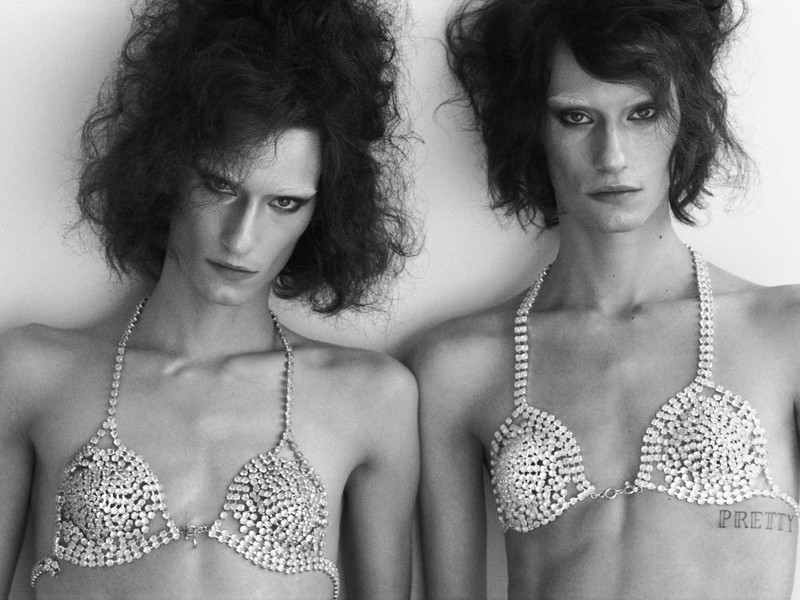

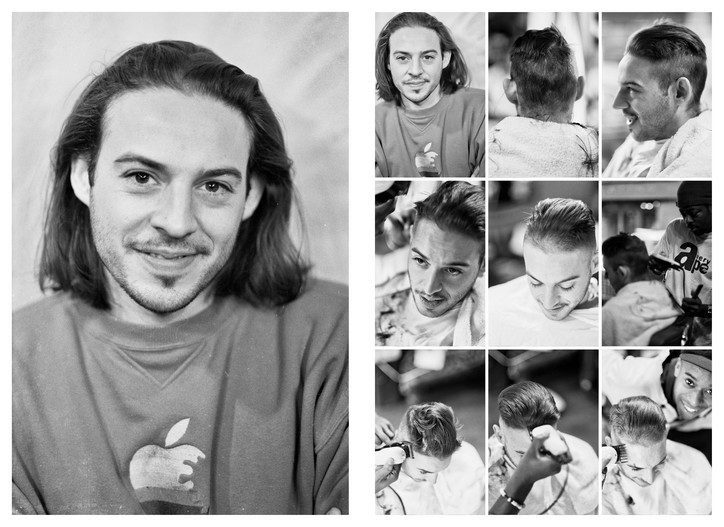

You capture such an intimacy in your photos—whether it’s just the client alone, or the relationship between the hairdresser and client, you really capture it. Could you talk a little bit about the intimacies of getting a haircut?

There was always a conversation going on in the shop. Back in the day, you weren’t allowed to talk about sex, politics or religion. And that’s all we ever spoke about—and of course, whatever the latest soap opera was and who was getting shot or whatever. It was so unconventional. It had a real family vibe. That’s why I said before—if you were in Soho, you would pass by the shop and hang out for 20 minutes and have a chat, even if you weren’t getting a haircut. It was that sort of a place. But there’s an intimacy with cutting—I don’t cut hair—but there’s an intimacy, a connection because you’re touching the person and you’re touching their heads. You know what I mean?

Right.

There’s this whole thing with the client and their hairdresser. They would tell you what’s going on in their lives. You’d never ask where they’d been—like, the standard questions, of where you’ve been for your holiday. That was a non-question. It was like, ‘How is it going, what’s happening, how are you getting on?’ Of course, every hairdresser has their own relationship with their client—every hairdresser has got their own personality. I always see clients gravitate towards the person they feel most comfortable with. But it’s interesting what you said about intimacy, because I was thinking yesterday about how when I was taking the photographs, it was about these short-spaced bursts of intimacy that I had with people, because intimacy has always been a little bit of a problem with me.

Really? How so?

Just because of my childhood. I’m fine with talking with people, but when you’re photographing somebody, you have to make them feel safe. I haven’t been taking photos for a decade. So, when I was looking, I noticed that there was this intimacy with them, because I looked into their eyes. There’s something really real about people letting me in and being themselves. I don’t have Facebook and all that stuff, but people—and even I do it now—they put their hands up in front of their face and suck in their cheeks in. You’re putting on a mask. With my photos, virtually nobody put on a mask. And that was beautiful.

It’s amazing to be able to reveal the truth, even if only for a moment. Your photos really do resonate with me because you do see a lot of truth.

Yes, thank you. The other interesting thing that just occurred to me this morning when I woke up was, they’re the only photographs I’ve ever taken.

Do you think your drive to take photos vanished with the sort of spirit that birthed Cuts?

I just think I started taking photographs partly as a record, partly through blocked sexuality, partly for creativity, partly out of boredom. What I used to do is, I generally look at the back of the book. At the very last few pages you see the contact sheet, and that used to be the finished product. I never printed up any single photos ever. I used to tell the clients, ‘You get three shots, and whatever happens in these three shots, if you’re blinking, if we mess up, if I mess up, if you mess up, that’s the finished—that’s what’s going to be seen.’ So, I’d print up the 1210 contact sheet and stick it in the window of the shop, and it would stay there until I finished the next contact sheet. Then I’d just put the one that was up away in the cupboard. That’s what happened for 15 years. But I felt I needed to make them for them, because they were trusting me—they were putting their trust in me. It was like, ‘Here’s my image, here I am standing in front of you, and do what you will.’ I used to tell them, ‘Don’t worry, relax, breathe.’ Then I’d sit with them with a bit of conversation about rubbish. Then, when I realized that I framed it correctly, I would say, ‘Now look at me,’ and ‘Okay, put your head there,’ and that’s how it was, really. It wasn’t anything more than that.

It’s very interesting to not only feel a connection, but a kind of a mutual understanding with what seemed like so many different subjects. What was that like?

Yeah, I think there was a deepening of the connection because there is that African saying that, ‘You must never let your image be given to anybody else because then they own you.’ I’ve been talking to photographers recently—lots of my friends, and friends of friends who were photographers that were getting their work published in the magazines. It was only just recently I was speaking to them, because of the book coming out, and we were talking about one photographer, and these were both guys that were taking photographs of women. I said, without going into the whole conversation, ‘You know, he always had issues around women.’ I think photography, for him, was a form of control and sexuality. You’re in this safe environment, but you’re in control, and you’re pulling out their sexuality, and you’re forming it into what you find sexy. And you own it. Do you know what I mean?

Absolutely.

So, there’s this deep thing going on. Then I spoke to Mark La Bon, who’s the editor of the book, and I was saying that part of photography, for me, was about expressing my blocked sexuality. He said, ‘Yeah, of course. It’s about control.’—basically exactly what I said. So, there’s this deep connection and intimacy. And when I took the photos, I was the one in control. It was safe for me.

Looking at your photos, it seems like some people felt little bit vulnerable in front of the camera, while others seem a bit cocky. It’s interesting to see different effects that the lens has on people.

Yes, yes. Obviously, I work with that. I could see the vulnerability in one image in my head now. For me, it was all about the framing. I’ve got basically the chest upwards or just the head—it’s just about fitting it into the frame, so it looked good. But then I would be standing there and say, ‘Okay, I’m not looking deep into your eyes, so don’t feel like I’m penetrating your soul.’ I’m looking at you, but I’m not going into your eyes. So, relax. Then like you said, you can really see some of the people looking back at me, feeling strong. Others look so childlike and vulnerable. I always wanted to catch that. But for me, I look at some of them, and you can just see pain in their eyes. I remember when I’d be looking at the sheet going, ‘Wow, look at that,’ because I don’t think they knew they were expressing that. But obviously, they did feel safe enough to look at me from their real souls.

What about self-portraits? Have you ever taken them? Do you think you’d achieve the same result?

No. Actually there’s three sets of pictures in there of me, but I didn’t take them. Each time, one of the clients would say, ‘Okay, now I’m going to take your picture.’ They would take the camera off me and just do it. So, how could I say no? I mean, they just agreed to letting me taking their picture, so I had to do it. But no, I’ve never taken pictures of myself.

Why? Do you just have no interest in it?

I suppose no. I mean, I could have done it. Once, when I was 19, which is back in 1979, I took a picture of myself—the classic thing everybody does when they first get a camera. You know, you standing in front of the mirror and you just click. Apart from that, no. I haven’t. I think that’s basically because I’m photographing myself constantly, 24/7 in my head. I’ve always got this self-examination. I’m quite split—I have split cells and there’s part of me constantly writing notes down. Even when I’m bawling my eyes out in my deepest pain, there’s this little part of me going, ‘Oh dada and dada.’ It’s more like the therapist writing stuff down so I can remember what’s happening.

Sometimes it’s easier to sort out your problems on your own.

Yeah, for me, I was always very closed down. Then, in my early 20s, I took myself to therapy, but it didn’t work. Then I got into hardcore drugs—heroin—for at least until I was 28. In fact, I was taking heroin when I first took myself to therapy, and that’s probably why I went. Then I went to NA for about six years, and that really opened me up, and made me be able to speak about myself. But I’ve always—even if I am sharing in group—I’m still there watching myself and trying to heal. So, yeah. I definitely think we are our own healers. But it can be to a fault. Luckily, I’ve now gotten to a point where it’s not so much thinking so much, it’s more just feeling—just feeling the pain. For me addiction, whatever the addiction is—if it’s drugs, if it’s sex, if it’s money, if it’s gambling, whatever—it’s all about not feeling, about distraction. So, the cure is to actually feel, especially because that’s what we’re trying not to do constantly. We’re all constantly trying not to feel.

Do you believe that photography is a sort of therapy in itself, because it forces you to face something that’s real—or encourages you to do so?

Yeah. Sometimes, you do see an interesting face, but I’m sure you are pulled to people that somehow reflect you. Whether it’s your light side, what we like to project to others, or whether what Jung calls the shadow side, that which we want to reject. So, yeah, I think photography can be a great form of therapy.

What’s next for you?

We’ve got a film coming out called No Ifs or Buts. The director is Sarah Lewis, and it’s being shown at the British Film Institute London Film Festival, this October. It was made over a span of 21 or 22 years. In fact, it was Sarah who initiated the book, because the photographs themselves got thrown away once and rescued. Then Sarah got them at some point and kept saying, ‘This should be a book.’ Of course, I’m thinking, ‘Oh yeah, Sarah, whatever, leave me alone. Who is going to be interested in these photos?’ She responded, ‘Your self-worth is terrible. If only you could see what I see.’ Then she contacted a friend of mine, Michael Koppelman, who ended up publishing the book. It’s only when I actually thought about it I realized, I’m so pleased that Sarah and Michael did it, because Cuts has a nice little feel to it—it really does.