Currently, more and more gay men seem to be on OnlyFans and similar websites, which feels like an extension of apps like Grindr and Scruff. It isn’t necessarily bad. I find the openness to public sexual expression fascinating and there are positives to it, but are we missing out on something more visceral?

SS— This is an incredible subject. I read today that X (formerly Twitter) has officially announced it welcomes all forms of pornography. All welcome, no matter what. I'm actually not on X, but I see obviously how sexualized it is. You might as well embrace it. I discovered Twitter a few years ago and realized it was like the porn central of the universe even then, to the point that I'd tell myself, No, I don't want to go there, because I'll get lost for two hours and don't want to do that. I can just jerk off in 15 minutes, but it's so fucking addictive.

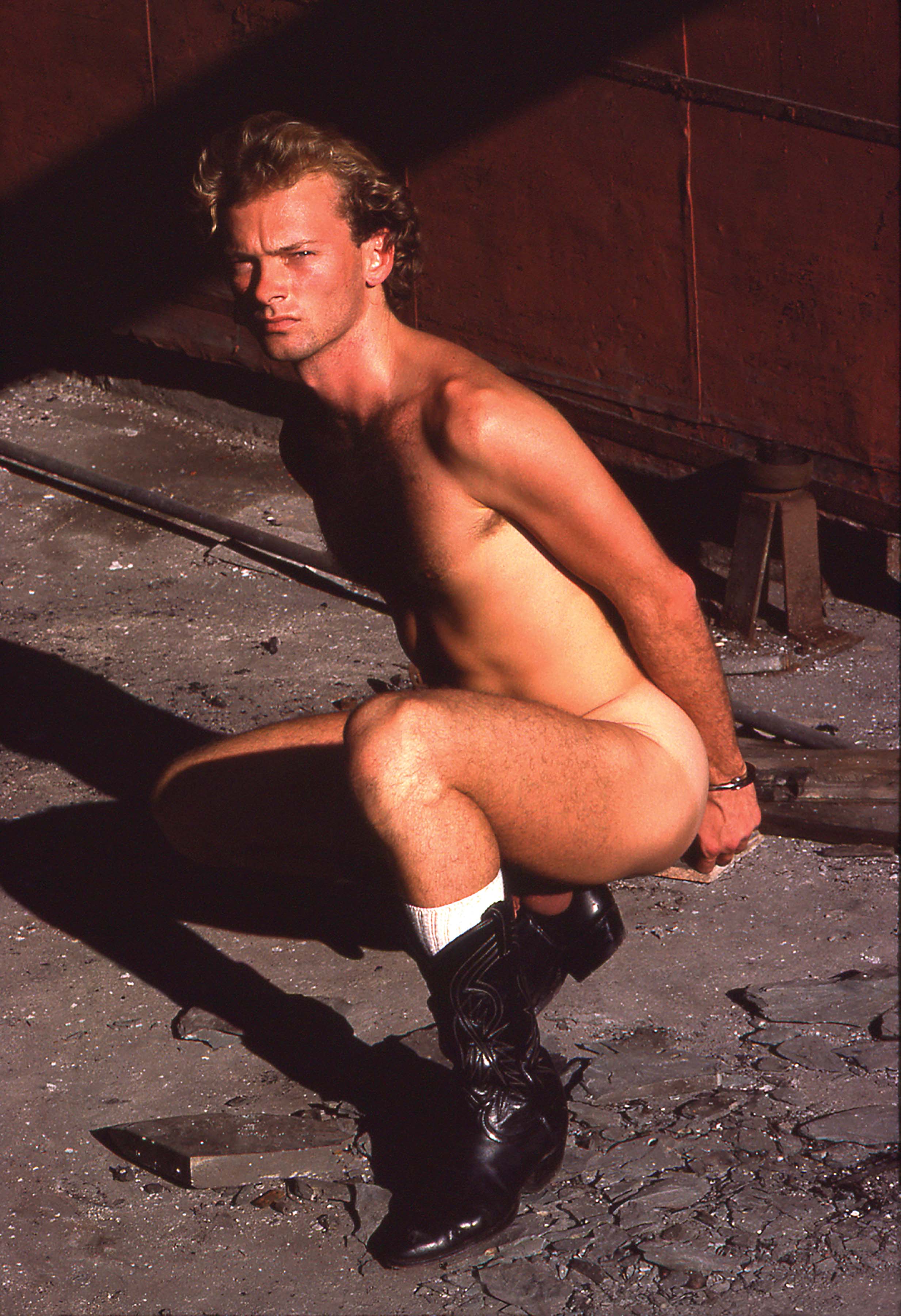

What impresses me are the images some gay men create unknowingly. I take screenshots of videos that strike me, and then I’ll look at them, and it'll be fucking perfect. They’re not my images; they’re folk images, sexual folk images.

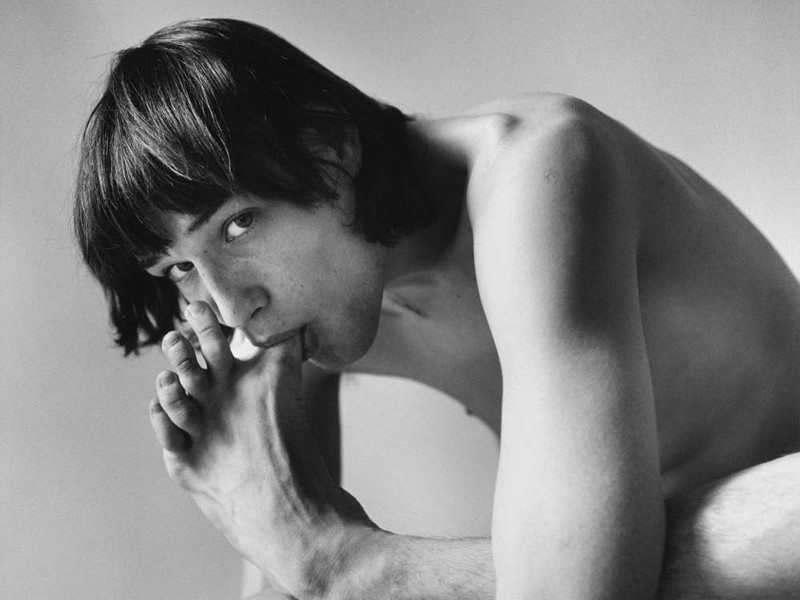

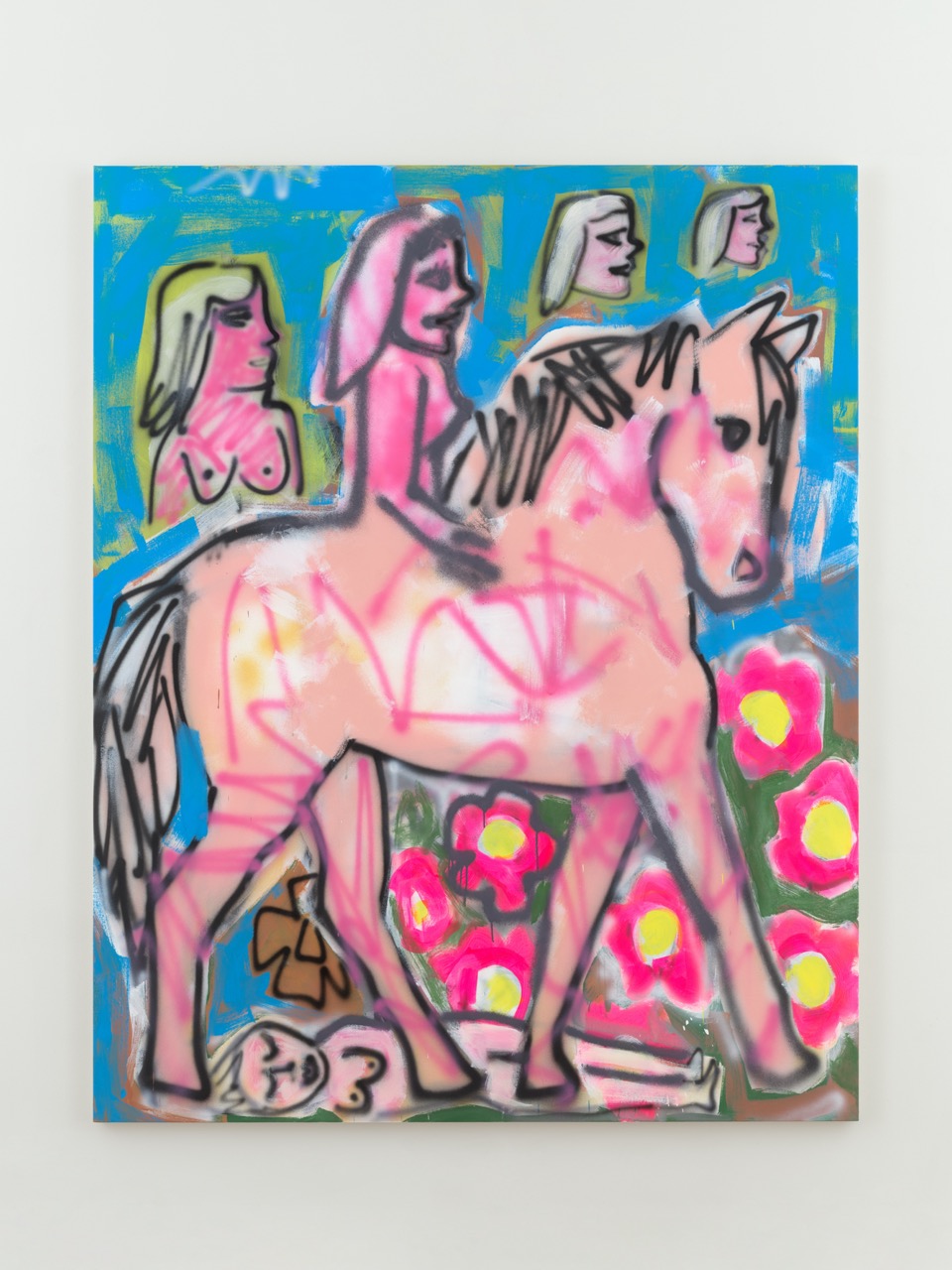

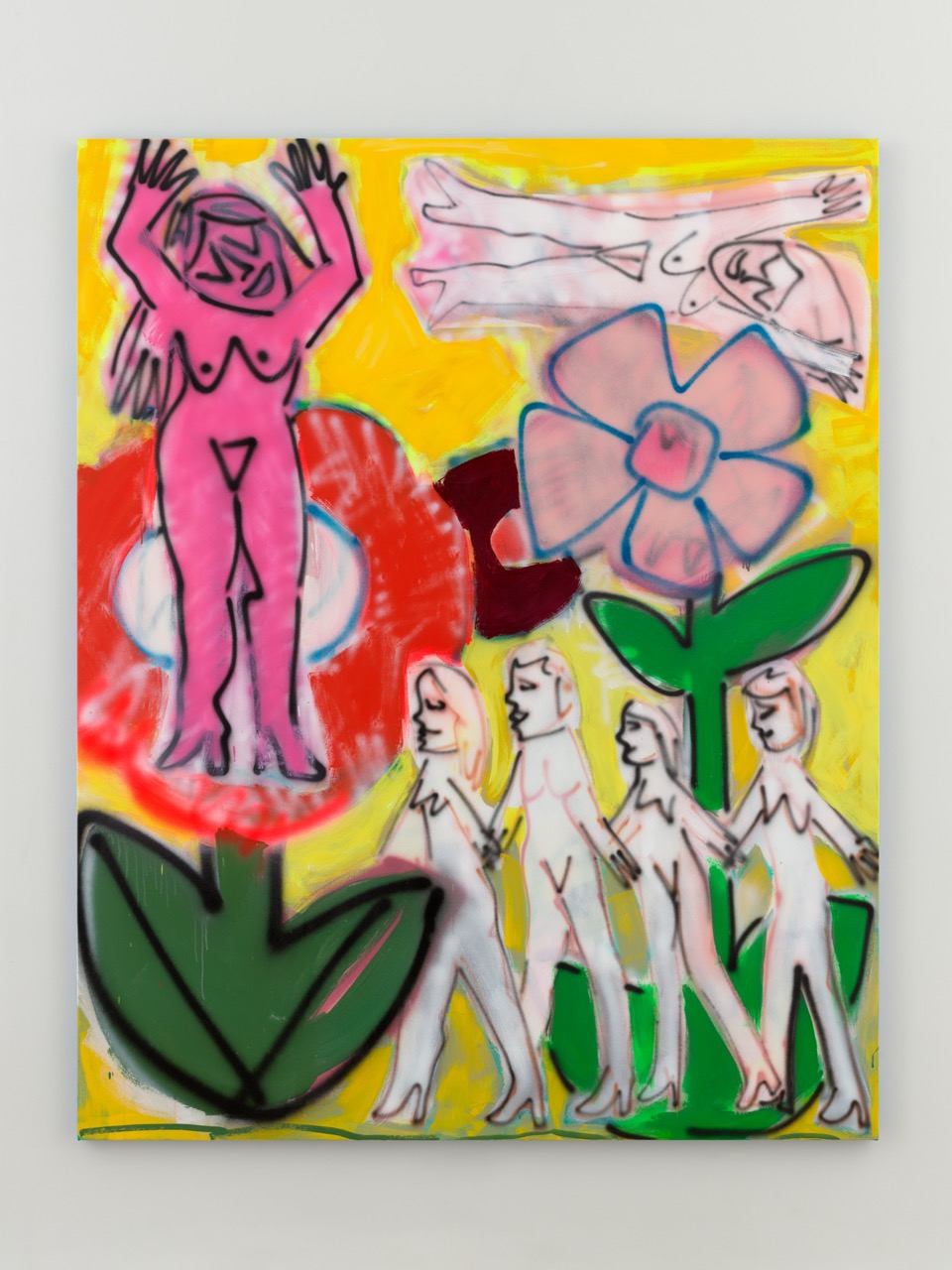

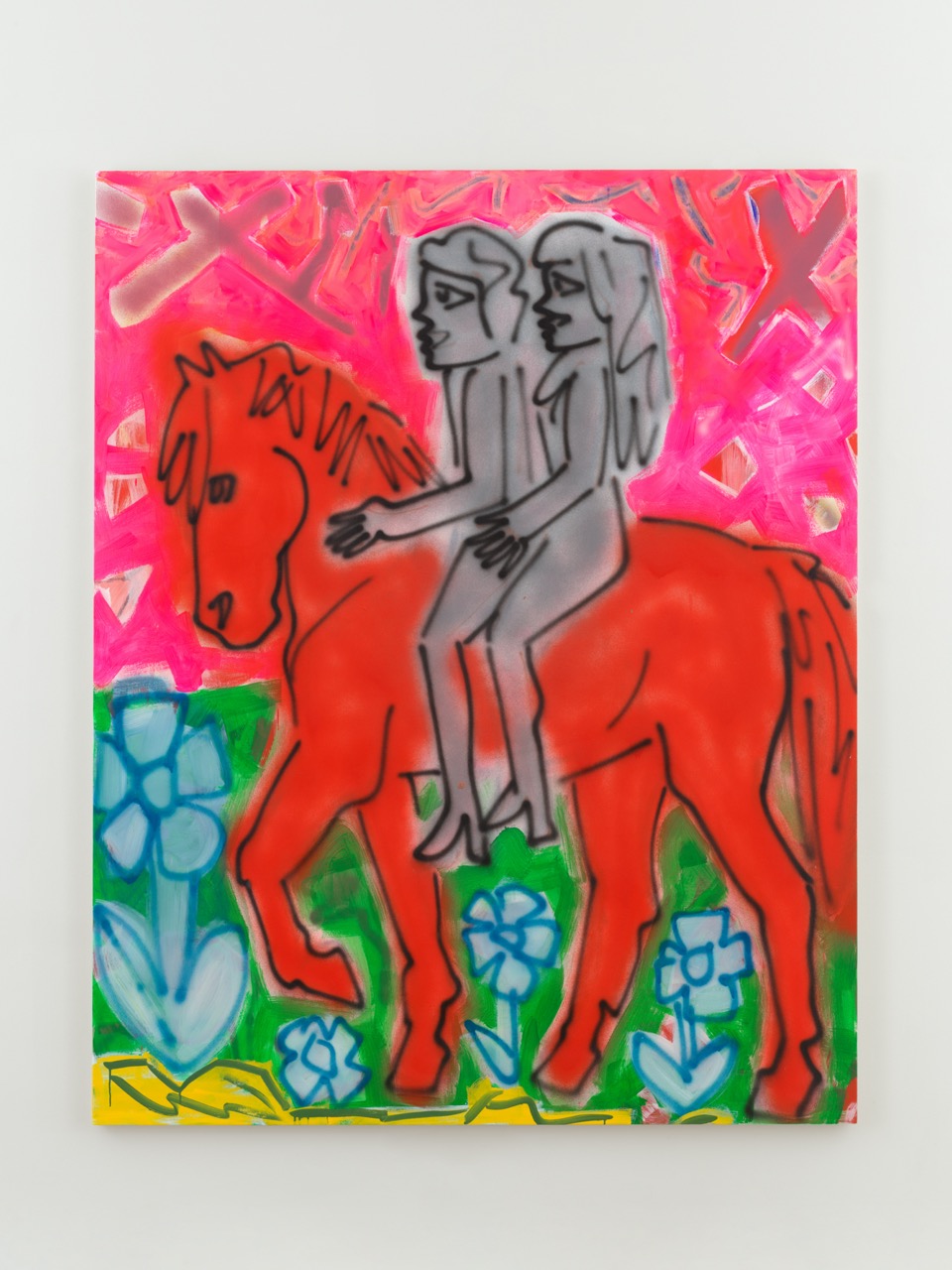

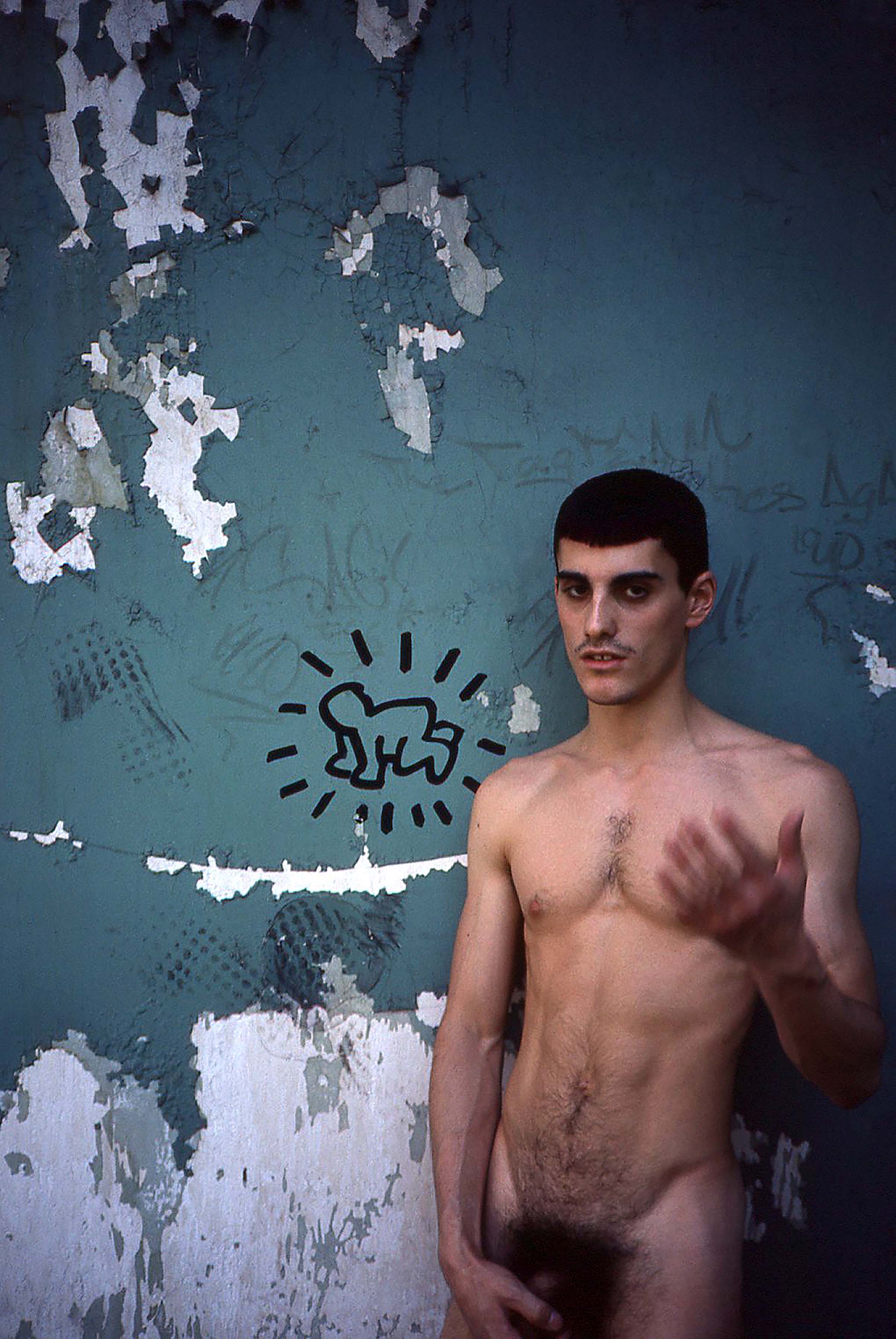

AF— It's true. I've been painting from old master paintings a lot recently but I'll also look at pornography, particularly nostalgic pornographic images, and these images have a directness that, while totally removed, communicates with you in the same way that an old master does. While I’m not comparing them to a Caravaggio, there is a familiar immediacy that grabs your attention and moves your eye across the page. The challenge for me is to use that impact to infuse the images I make with feeling and humanity, but there’s no denying the powerful graphic immediacy of these images.

SS— And I don’t think anyone is doing this consciously.

AF— No, not at all.

SS— Exactly, and since it's not conscious, you can say that these people are just creating primitive folk art; what gay men have always done, made art out of sex. It’s not about the act itself but about the art being made and it’s not surprising, except now it's spread across media, platforms, videos, and even AI, so people don’t recognize it.

Yeah, and it’s also quite normalized now. In the past, someone might have been fired for being publicly sexual, but today, it's common for people to have an OnlyFans while working a 9-5. Or you might know someone whose nudes are online, and it's no longer a big deal.

AF— Right, but now everything’s become a part of our profiles — what we buy, where we go, our friends. I miss the times when you had to go out and talk to someone, though it still happens. For me, meeting someone in person is still the most exciting way.

SS— It makes me think of how gay men used to meet — nothing was as abstract as it is now. Decisions were based on initial desire, interaction, and chemistry. You could smell and touch the person. Now it's reduced to text boxes. It frustrates me that we sell every part of ourselves, even the most private. It's not about subverting privacy or doing something kinky with someone anymore; it's about fan numbers and money. It's like bye-bye humanity. But of course, Alex, I'm sure there are places in Paris where you can still meet in this way; they have a better sense of that style.

AF— You have to come to Paris Stanley.

SS— Well, I know I have to come to Paris.

AF— And I agree with you. It's the age we live in. Everything has become commodified. Yet, there are still ways to connect genuinely, as your work shows and it is possible to maintain an authentic self even if it's hidden. That's what I look for in everyday life now, moments of actual connection.

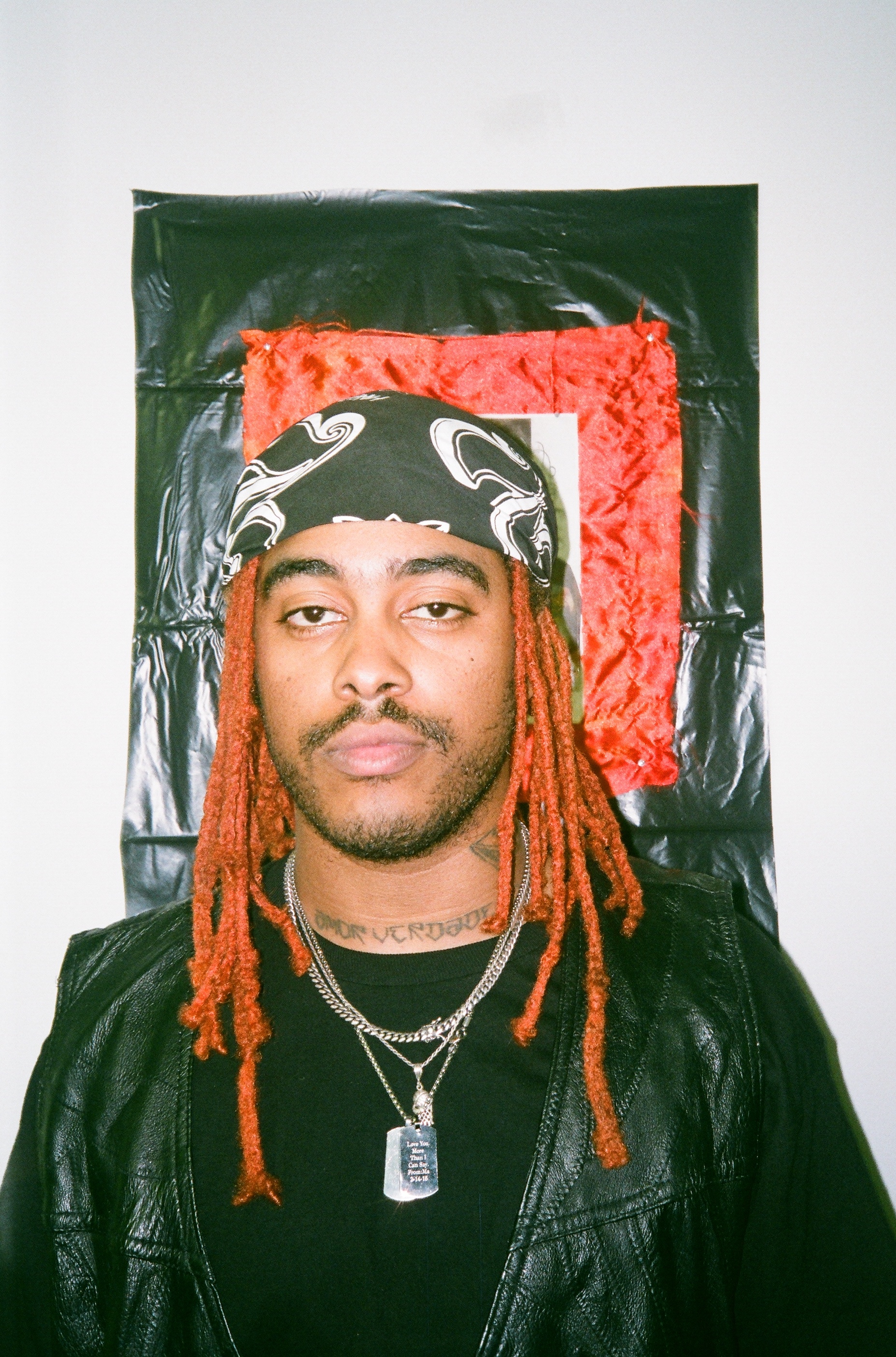

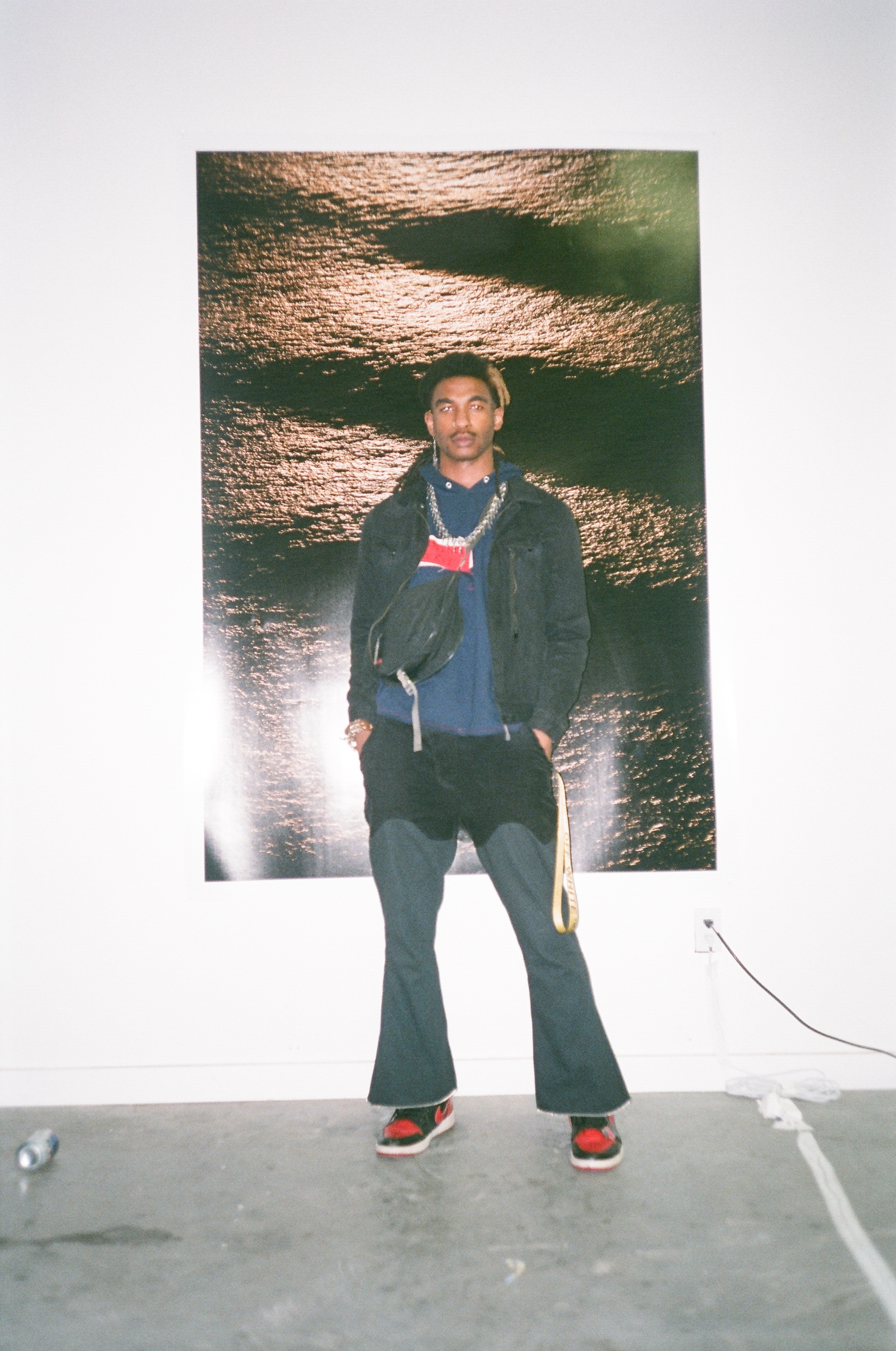

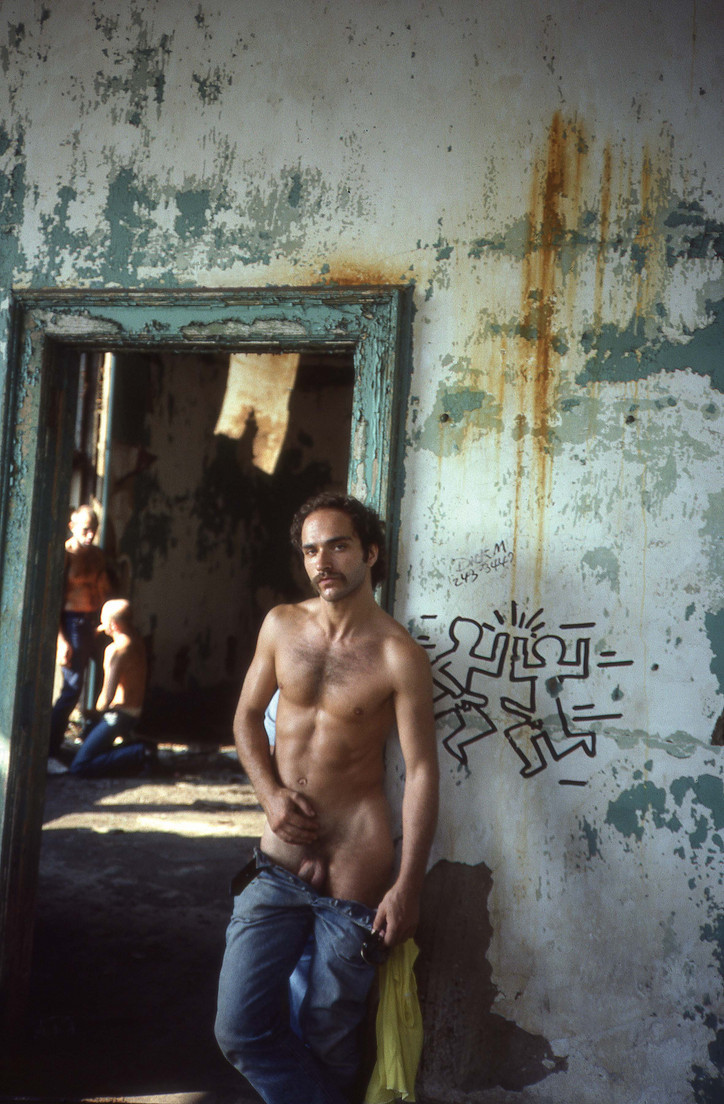

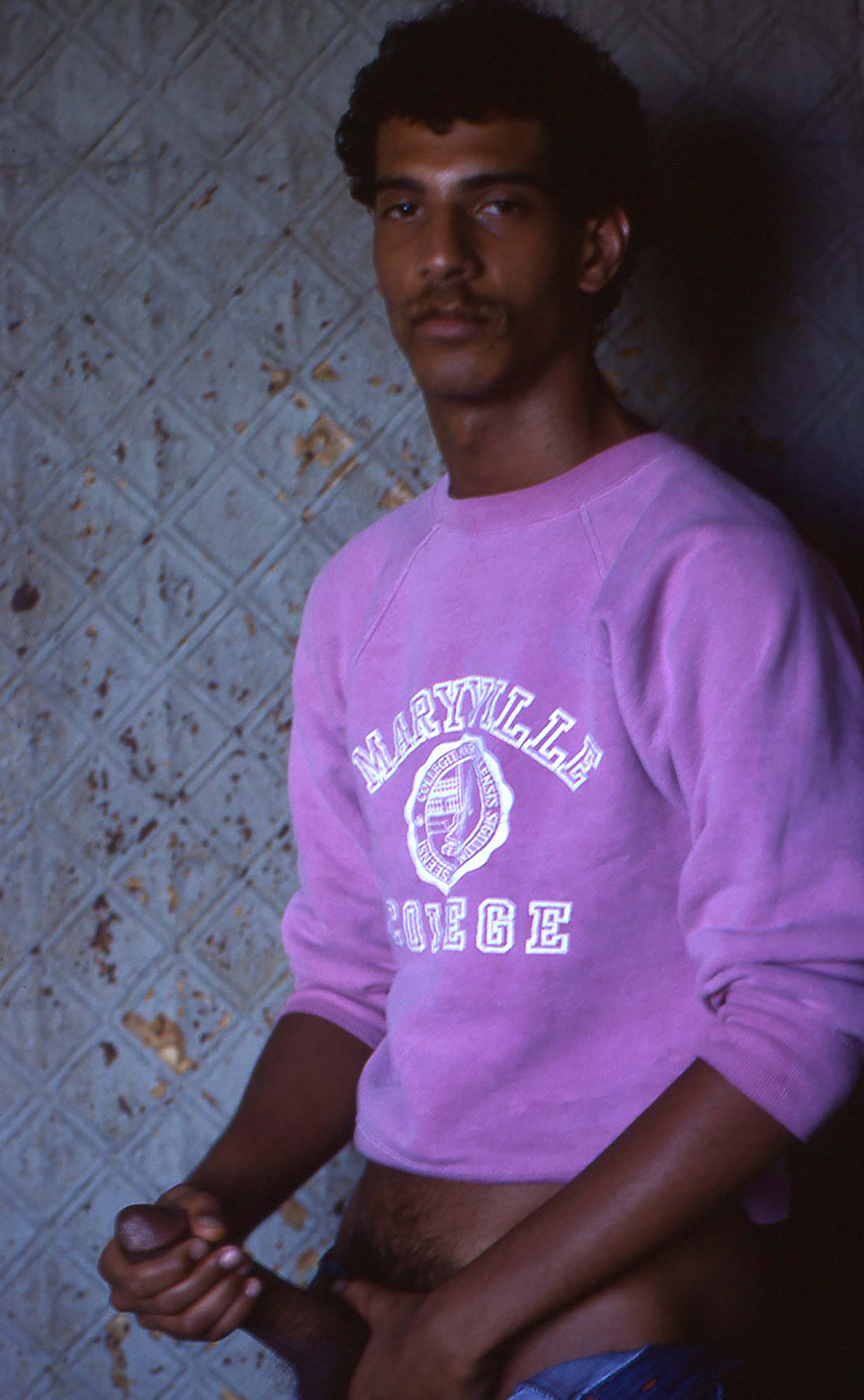

SS— I enjoy my shooting so much now. It’s unusual for me. The guy who was here yesterday, I’ve known him for years. We’ve done three shoots together, and we finally reached a level of honesty where I could ask him to wear his cage on his dick and to also himself formally, as if sitting there in a suit. I actually see a lot of my studio work now as formal portraits — the secrets of the people I photograph woven into the visual design of how I perceive and love them. You know Sahir, I don’t say this to make you uncomfortable because I see there might be ink up that sleeve. Tattooing in gay men is one of my genres. It’s a subject not many people discuss articulately, but it’s huge for me. I could talk about my involvement, history, research, and the symbolism used by gay tattoo artists, and in their tattoos, to identify themselves for a long time.

AF— What was it exactly? Was there a word?

SS— Oh boy, that culture isn't even around anymore. I often mentioned it to the Leslie Longman Museum when I worked as their staff photographer for some years, and they didn't know what I was talking about. Or I'd show them some incredibly inked gay man, and it wouldn't interest them. They couldn't relate. Tattoos have always been seen as a fetishistic art form or a personal eroticization of one’s body.

Now it's almost the opposite. After five years of shooting with the guy I shot with yesterday, we've developed a shared language that only comes from deep comfort and trust between two gay men, which also allows the portrait to be vibrantly beautiful and alive. It's all about perception. I'm glad to perceive people in their sexual selves as just one part of who they are. Removing the sexual doesn't remove the essence of us, and you can never take it away from us either. It's not us if you take the sex away.

I’m feeling strong doing what I’ve always done, but it’s now more acknowledged and visible. The combination of sexuality and humanity is easier to see. The shift in how sexuality is sold and discussed is now more familiar to people, but it’s not my world anymore. I mean, I have a good life, maybe better than ever right now, but I don't know when it was that the world shifted. Everything I learned growing up is just OG. That's what 20-year-olds are calling me — the OG, or the old gay. Do you know that phrase?

AF— [Laughs] I didn't think of OG as old gay, but I love that.

SS— Well, what did you think of it as? What is it?

[Laughs] I know OG as 'original gangster', but I like old gay better now.

AF— And then GOAT is the greatest of all time, which you are Stanley.

SS— I was shocked when someone first said that to me actually, that I was the GOAT — I'm a Capricorn so that fits — but to be considered "greatest", I'm just used to being thought less of, not more of.

AF— No, no. Stanley you are the GOAT.

SS— Well that's just part of my struggles and history, my own understanding of being in junior high school in New York City and feeling alone, wondering who else was there with me and how they were reacting to me or ignoring me.

AF— Right, how is it that we find each other?

SS— I think we could do a better job.

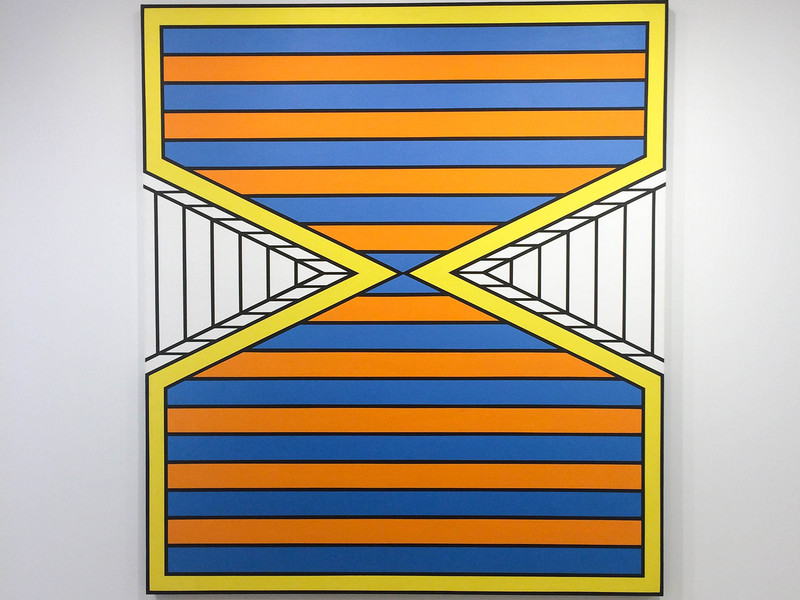

AF— This makes me think of what you said earlier about seeing freedom in my work, which I also see in yours. We grow up feeling hemmed in, trapped in our own little cages, trying not to draw too much attention or make any loud “faggy noises.”

Once we break free from that, we’re left with the opportunity to celebrate our newfound freedom and express it as fully as we can. That’s what I strive to do in my work. Though I’m not naturally gregarious, I find that I can express that freedom through my art.

SS— I ask everybody I photograph to tell me a story. Generally, people either freeze at that idea or tell me a story that often leads them back to their coming-out experiences. Everybody has their own version of it. I've always wondered why we don't embrace and love each other more than we do, why so much of our interaction is based on whether we want to have sex with each other.

I remember being in junior high school, there was another gay person, and wondering why, as the only two there, he wouldn't talk to me. And he never did. Could it have been my sneakers? Something else?

My history as a homosexual in the mid to late 20th century is loaded, and it hasn't faded away for me. It comes up everytime I shoot someone. I know that many of the men who've walked into my studio have never had the opportunity to be as honest and open as they can be there with me, which is why my photographs turn out the way they do.

AF— You do have a way of putting people at their ease. I remember that.