Leading up to the cookout this summer, you’re all planning to do a number of additional activations. What are those activities going to be?

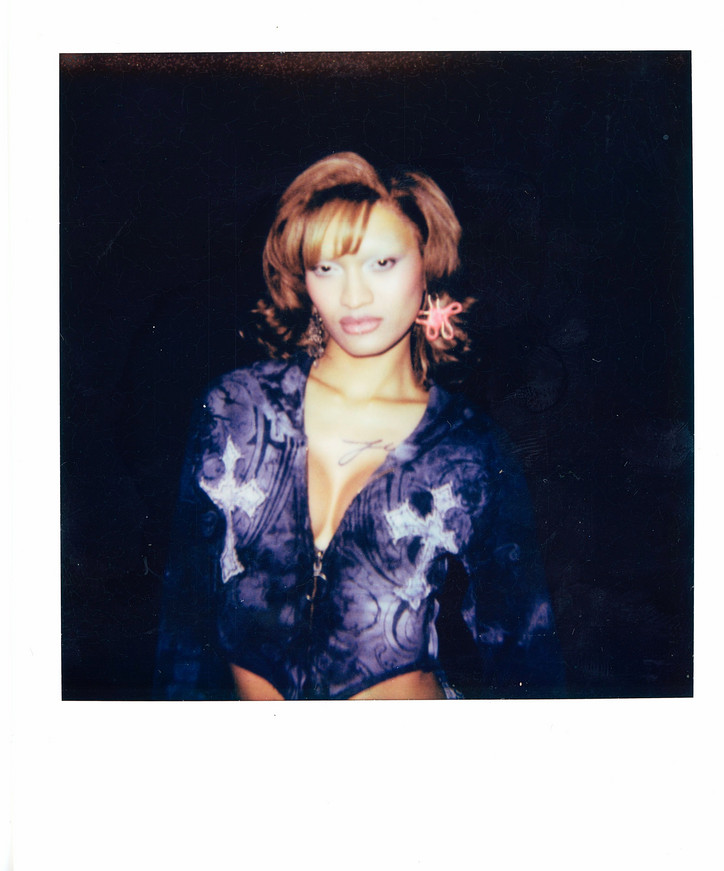

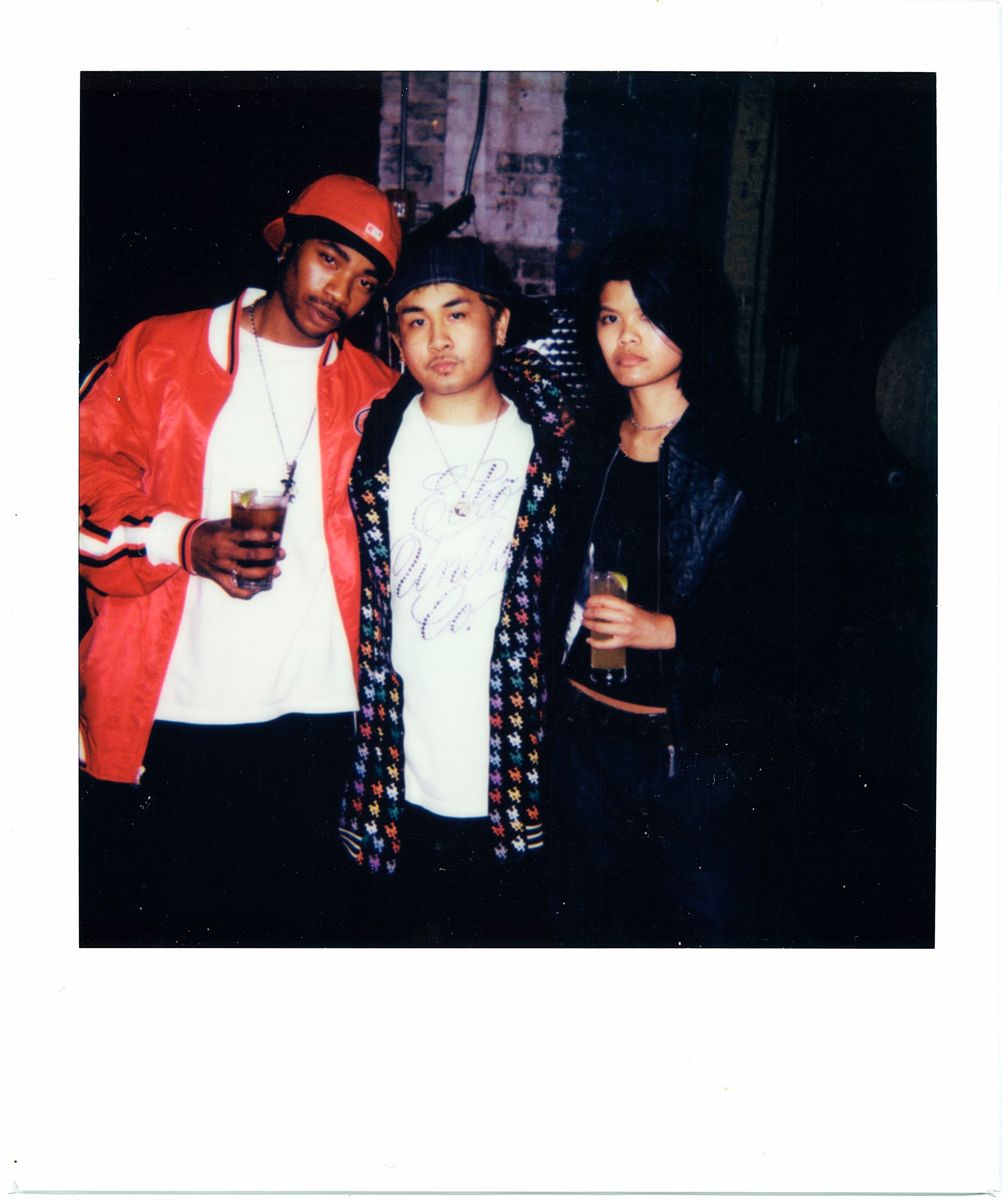

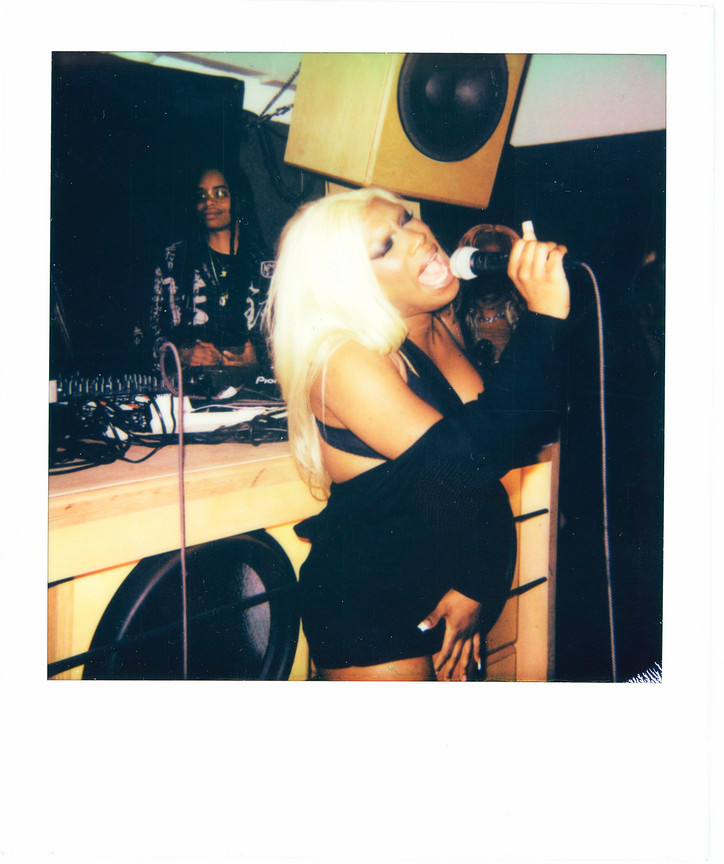

GIA - Over these last few months our team was in an extensive pre-production phase for all the programming we have planned in the coming months. As we look ahead we will be partnering with other NYC party collectives to fundraise for the cookout, as well as hosting various wellness/knowledge skill sharing workshops. We are excited to introduce our newest programming with our community cooking classes in June, as well as our garden Wellness Activations, where we create access for our trans siblings to learn to garden, participate in ear acupuncture/cupping, sound bowl mediations, dye workshops and our T4T clothing swap. I’m also personally looking forward to continuing leading our Heal In Restorative yoga series. It's been fulfilling to show up in this work and feel equally supported by my community as I deepen into my practice as a teacher. Lastly, at the end of the summer we will be hosting a special awards ceremony dinner where we will be honouring trans femmes in the community who are trailblazing and leading important work.

Most of the fundraising I see happening in the Black trans community in New York is intra-communal. It’s the dolls taking care of the dolls, raising money for each other’s surgeries, or rent, or other means of survival. This, to me, is beautiful, but also problematic, because there’s already a limit of resources. Can you talk about the difficulty here and the necessity of external support?

SOLÁNGEL - That’s the reality. It’s the dolls holding down the dolls. We organize, we crowdfund, we make a way out of no way. That’s beautiful — it’s ancestral. But we can’t keep pulling from the same pot and expect to build sustainable futures.

The truth is, outside support isn’t just helpful — it’s necessary. We need people and institutions with access to real resources to redistribute, not just reshare. This isn’t charity — it’s a call for material solidarity.

At our 4/20 event, we raffled a $300 gift card donated by K.NGSLEY to support my recovery fund as I prepare for gender-affirming surgery. That’s community care in action. But we shouldn’t have to rely solely on each other to survive — we deserve systems that allow us to thrive.

I know this doesn’t necessarily fit in the tapestry of these questions, but when I was last in town, Indalesio, a great friend of the collective who first envisioned the Black Trans Dinners the Angelito Collective has been hosting since 2021, was in the midst of a back-and-forth with Greenthumb and Parks NYC, who were trying to shut down Sunset Garden because the girls refused to remove an altar to Cecilia Gentile. Do you want to talk about what’s happening with that, and how it fits into the broader issues you’re all battling in your work and lives?

SOLÁNGEL - What’s happening at Sunset Garden is part of a much larger issue — this administration's obsession with erasing black trans presence from public spaces. Let’s be clear: trying to remove a memorial to Cecilia Gentile, a Ridgewood native isn’t about park policy, it’s about control. It’s about telling trans people our grief, our joy, and our lives don’t belong outside.

This shows up everywhere — from parks to workplaces. At one of my last jobs, a restaurant that claimed to be “for the dolls,” they didn’t even bother to fire me. They just stopped putting me on the schedule. That’s how transphobia plays out: quietly, passively, but with very real consequences.

And with all this anti-trans propaganda in the air, people are getting bolder in their bigotry. But here’s what they forget: trans women have always gathered, created, and cared for each other. We’ve always found ways to protect our joy, even in hostile systems.

We’re not going anywhere. Community is what sustains us. And we’ll keep showing up — for each other, and for ourselves.

INDALESIO - Over the years Sunset Garden has grown into a key space for our community—a site of joy, grief, nourishment, and resistance. We’ve celebrated Trans Days of Visibility here with healing modalities, and we do it year-round, across the seasons. We grow food in the garden for the dinners themselves. The space has become a place of access—a place where trans and queer people can exist in the daylight, without the pressure or expectation of nightlife. Historically, we have mostly had clubs and bars in the dark—but we also deserve softness, sun, routine, and the right to just be. That’s what the garden has offered. And that’s what’s at stake.

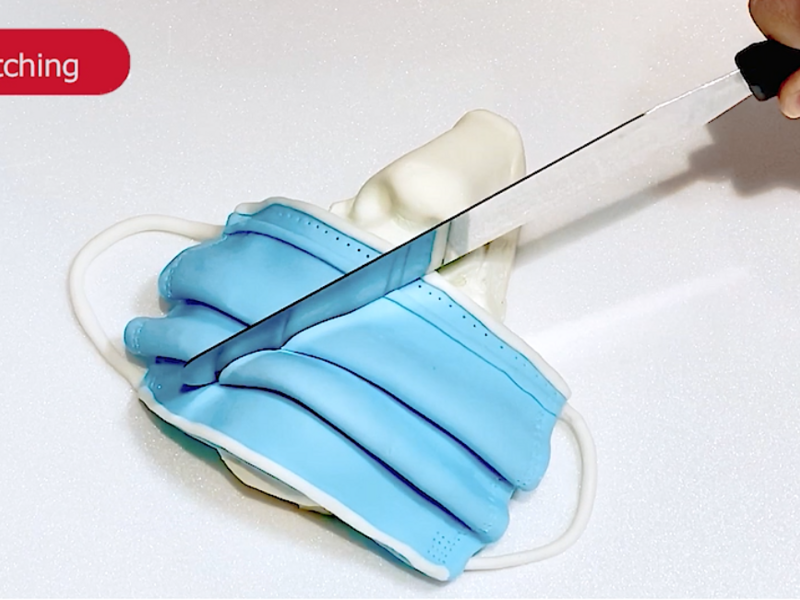

Since late last year, we’ve been caught in a drawn-out, exhausting back-and-forth with NYC Parks and Greenthumb. Though honestly, it hasn’t been much of a dialogue. Now they’re invoking Section 7(e)—a clause tucked into every Greenthumb lease—to justify terminating ours. The supposed violation? Refusing to remove Cecilia’s altar and declining to sign a separate lease through Art and Antiquities. That additional lease would require us to relocate the altar to another borough, bar it from any Parks or city property, and dismantle it completely after one year. We’re not signing that.

We see memorials all over the city—to fallen firefighters, to soldiers—but when it’s trans people remembering our own, suddenly it’s a problem. That’s not policy. That’s erasure.

These systems always come for the most marginalized first. They want to push us out of a space we’ve built with love, with labor, with our neighbors. That’s why, alongside our resistance, we’re committed to political education—making sure our community has the tools to name and disrupt the transphobia, racism, and Zionist violence that keep showing up in our neighborhoods and institutions.

We won’t be erased. We won’t be moved. Sunset Garden is ours, and we’re not leaving.