Tell me about the project.

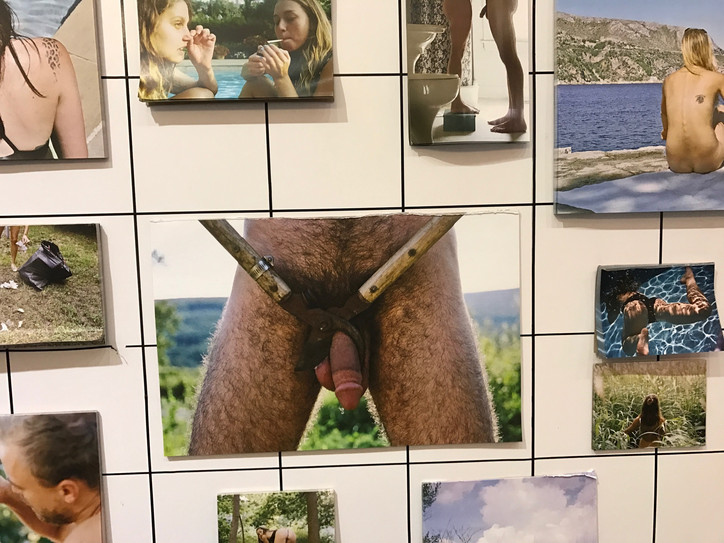

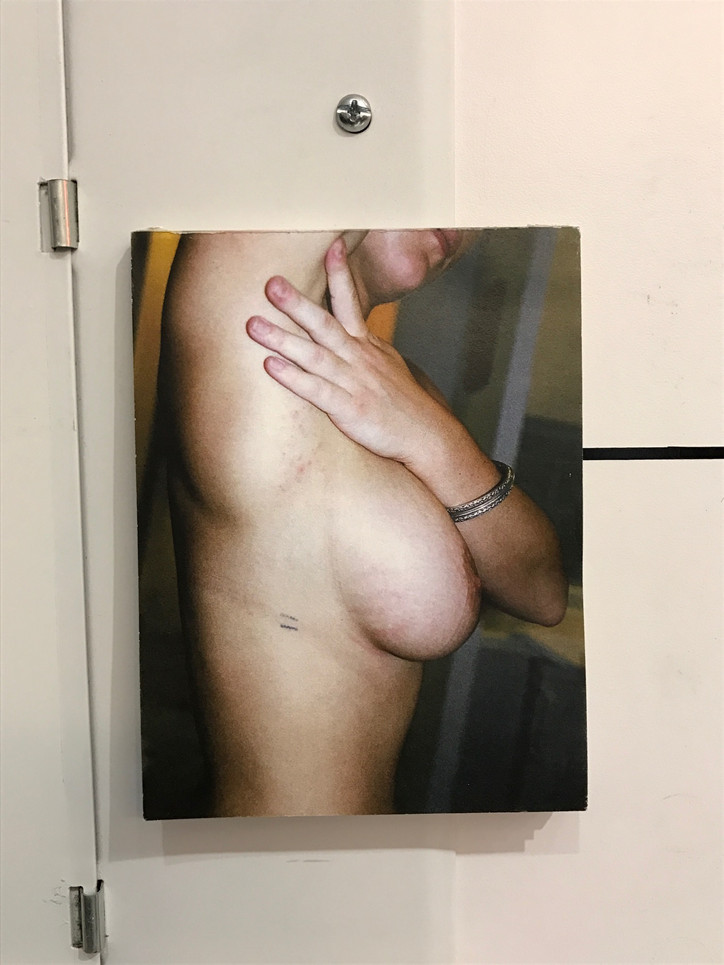

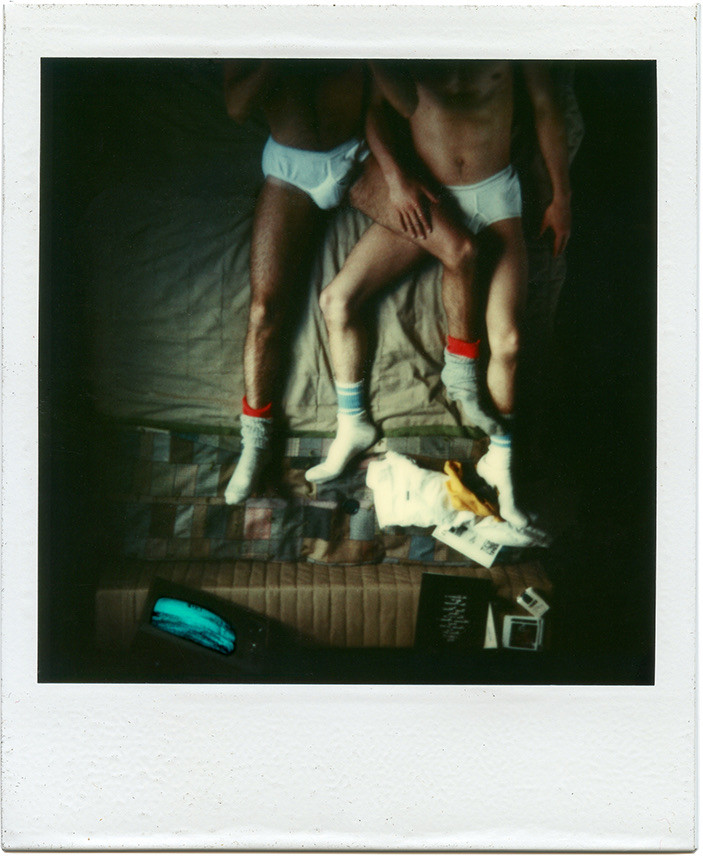

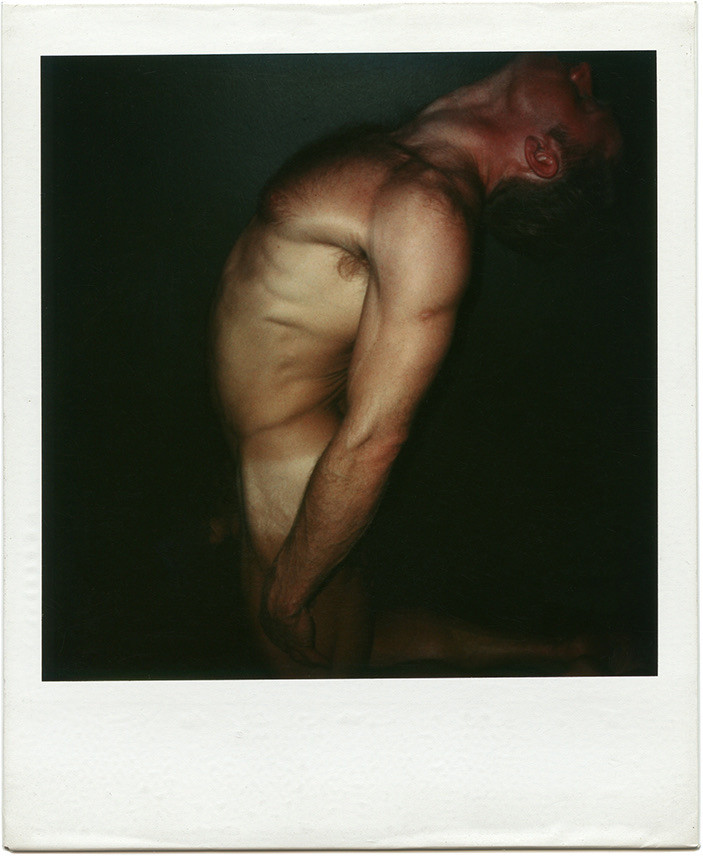

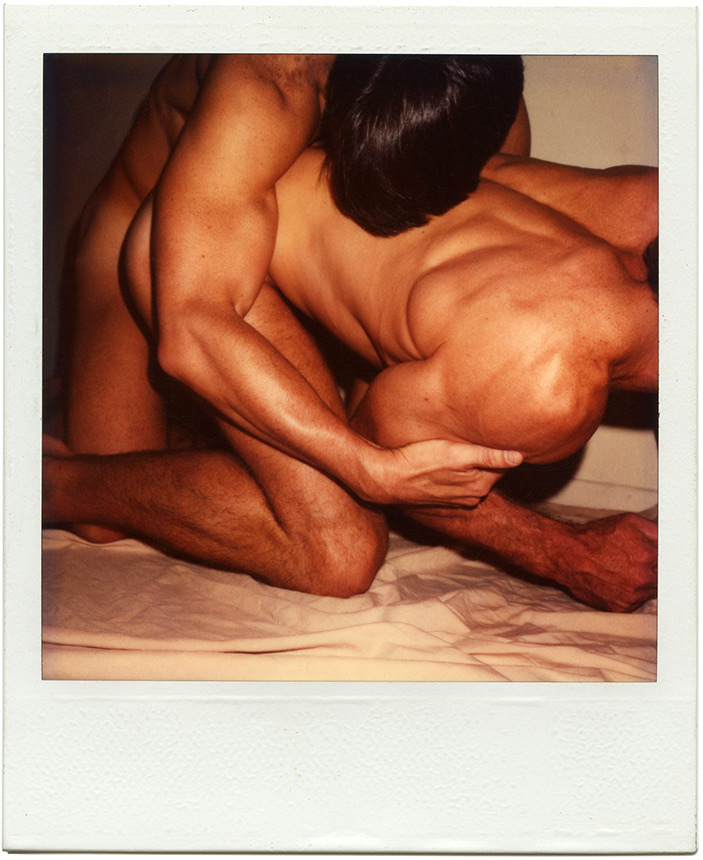

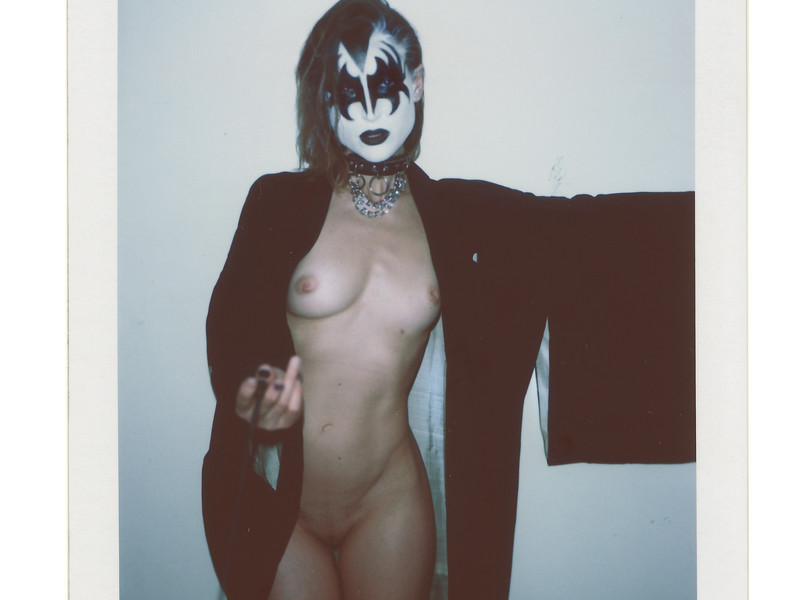

Back in the years 1975 to 1983, I had been given a SX70 camera by my employer, which was Columbia Pictures at the time, and I took the camera out to the beach and started documenting life in the Pines. And I really early on realized that I wanted to make a book of that material. I wanted boys like me to know that there was such a world that existed. At the same time that I was doing that, I had an apartment in Manhattan, 63 East 9th street, which is the title of the book, and I was photographing in the apartment at the time. The material was quite different from the Pines to the apartment, because obviously the apartment is a much smaller geographic space than Fire Island and the Pines, so it tended to be more concentrated, the images were, and skewed toward my and my friends’ intimate lives. And that material was pretty much hidden in that scene until very recently. When the Pines book was revealed, I also showed a few people the New York material, and we knew then that there was another book from the Polaroid material that I shot at the apartment.

Now this is all pre-AIDS, these years. It was a time when we were discovering the sexual possibilities of ourselves, heretofore that was an area fraught with issues—including the fact that we had to hide ourselves from society.

I’m so curious about the Pines and how it ended up being this gay mecca, and Fire Island in general—do you know anything about that, or did that just sort of happen?

Fire Island, particularly Cherry Grove became a place where creatives, particularly gay people went. You had people like Paul Cadmus, George Platt Lynes, Jared French going there to hang out. It was a place you could be naked and really free spirited. And as summers went on, it was considered a very bohemian place, there was a spillover into the Pines, which had been developing itself as a new community. Ultimately it became a community larger than Cherry Grove. It started with people floating houses over and then it turned into a place where people started building houses—quite wonderful ones, at that. It as a place for architects to expand their vision. And my apartment in New York, the design of it was influenced by the kind of lifestyle we were living in the Pines. I designed that apartment to be a place for sensual comfort, soft light, lots of banquettes, lots of mirrors, plate mirrored a wall in the living room, plate mirrored the ceiling in the bedroom.

Do you feel like the Pines contains a similar spirit today? How has it changed, or has it?

It can’t change physically that much—it can change with global warming with rising seas, it’s a sandbar after all. Socially, it was a place for creative types to find one another, and so it attracted from theatre, dance, fashion, all of the art forms. And that continues to this day, it’s still like that, it’s discrete in the sense of size—there are about 600 houses there, so there’s a limited amount of space, but it’s very concentrate in the creative communities. I find that people go there today for the same reasons that we went there back then: we wanted to connect with one another, we wanted to find one another emotionally, intellectually, sexually. That’s what we were looking for, and that’s what we found there, and that’s what continues to be found there.