For Eimear Walshe, There are no 'Goodies or Baddies'

Isabella Fox Arias — How does language play into your work? Despite using a visual medium, language is still omnipresent throughout.

Eimear Walshe — The process of making ROMANTIC IRELAND started with writing, and I am very word-oriented, even as a visual artist. Writing comes up high in my communication fluency areas, so my challenge for this pavilion is thinking about the three different things produced.

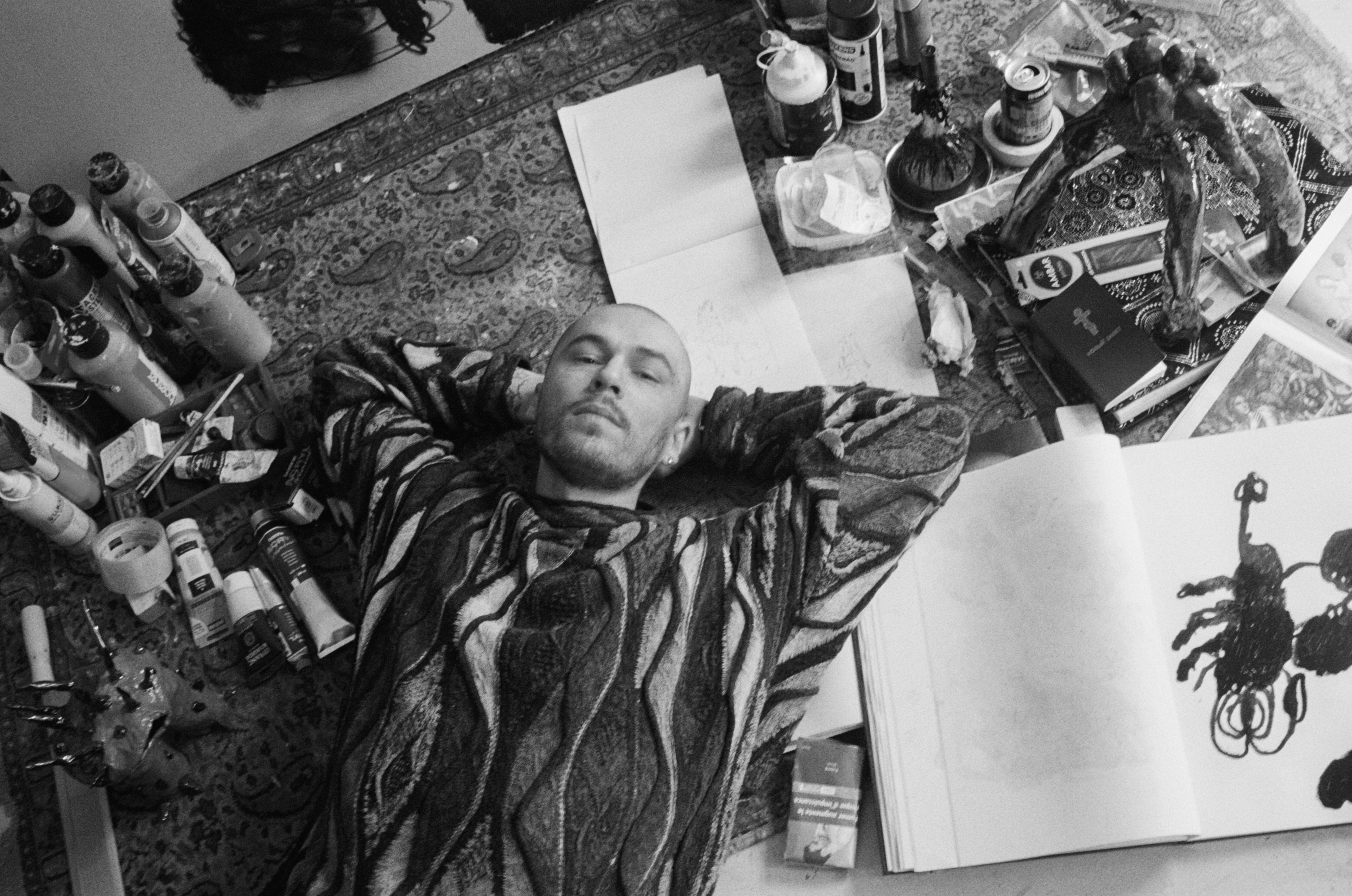

The first part is the libretto in terms of its development, and that's obviously a writing process. But the challenge with the other aspects, like the video and the sculpture, was to think through, you know, the performers don't speak; they communicate just through gestures.

That was a challenge because I want to get more fluent with working just through gestures. What better way to do that than through dancers with their own vocabulary? I was really lucky to get to work with the dancers, performers, actors, and musicians who convey without words. Then, through the building, it was like thinking about retelling a part of history just through the material itself.

I'd love to hear more about constructing the story of the building.

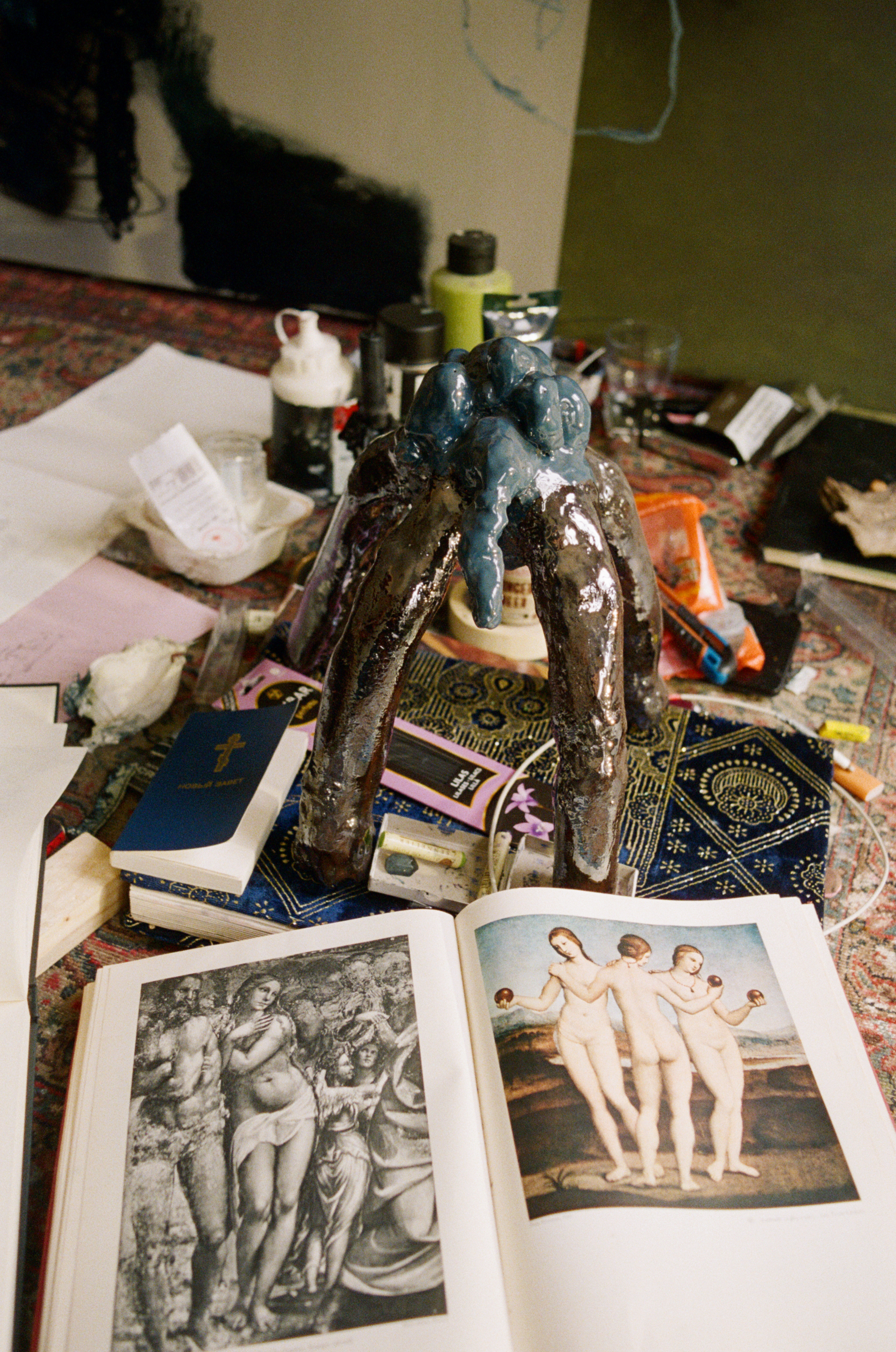

The libretto text was the starting point and, I suppose, is also like the temporal anchor point in the sequence where the video was set. It's the biography of a building — the building site is the before, the eviction is the destruction of the life of the building, and then the ruin is the afterlife. The libretto about an eviction became the fulcrum of the narrative arc of the pavilion. It's central and primary, but I think it's also something that I try to challenge myself with. That's why it's so special to get to work with other people: you find out their languages, their fluencies, and their modes of conveyance.

Have you worked with dancers before, or is this your first time working so heavily with just a movement-based language?

Yeah, this is my first time. I got Mufutau Yusuf on board at the very start. I did that because, in his work, he has the ability to communicate incredibly large volumes and intensity through very minimalistic gestures. Some of his works involve really explosive, hugely energetic movement, but then others involve microscopic movement, like having individualized control of a whole sort of fan of muscles on your body. That extends into the kind of narrative that he is able to make through those really microscopic movements. I remember seeing one of his performances that involved moving a bicycle a tiny bit backward and forward. It's just incredibly beautiful. That ubiquitous movement captured and repeated was really of interest to me in terms of the earth building. The brief or the remit for the movement and why I was so comfortable working with Mufutau as a choreographer was I don't really want there to be dancing. I wanted to be built around the types of movements required for this kind of labor and building practice.

Working with Mufutau, Rima Baransi, and Gallia Conroy, who were the crew members with strong backgrounds in dance, was really inspiring. They just have a different way of creating. I was able to write the scripts really differently than I usually would; I'm usually a little bit over-contrived. People who are improvisational dancers are going to challenge that. For some parts of the script, I just bought laminated photographs of pieces of furniture.

What kind of furniture did you bring?

One of the really important ones was a phone stand, which is a funny mid to late-20th-century piece of furniture that you'd have in your hallway. There's a little door, you put your phone book in a little press, the phone is up high, and there's a little place to sit. That appears in some of the photo documentation of the work. Erin plays the harp, so she needed a harp stool; my businessman needed a big mahogany desk, so we made that out of our bodies, and the landlord wanted to shit on everyone, so we made them a toilet. That was incredible because it was not an area of aptitude for me. It was really special getting to work with people who were not even exclusively in that field but who have such strength in that area.

That's wonderful! I was also interested in your choice of using masks for your dancers. I found it powerful that the identity was erased from the dancers, and instead, they became almost monster-like.

Yeah, I mean, those masks have really different associations for different people. People asked me the least about the sort of monster alien end of the spectrum, and I'm excited to talk about that, actually.

Really? It was my first thought watching the piece.

Yeah, I guess there is a spectrum of associations with those masks. Their primary use is their fetish objects, and they're from a latex company that produces custom whatever you want sort of latex pieces in any color. They're in olive green, so they also have an association with Ireland, the military, and the colors that were worn by volunteers in our revolutionary history. Also, any kind of face covering is often associated with clandestine activities. There's some kind of line between deviance and criminality when you have to cover your face because of what you're doing. Thinking about the different types of external forces that create the necessity for that but also thinking about, especially the fact that they all wear it even though they're all from different historical and class positions, this kind of universal marker.

The monster bit is really relevant because I'm thinking about the way that colonized people, whenever they resist in any way, shape, or form, including peacefully, are constructed as terrorists. That's definitely something that's at play with this. These constructions of forced clandestinisation, deviancy, and the relationship between armed resistance and liberty. All this is painted on them, and then they act out a soap opera. I suppose what I'm asking of the viewer is, can you when you see them go through all these daily activities, can you identify with them anyway, even though they've been othered by this costuming?

You mentioned otherness, which I felt while watching your work. You piece made me think about otherness and its relation to being a queer artist. You are non-binary and your work deals a lot with transient middle space that exists between two extremes. I’m thinking about how your work deals with coming from a land that was both the colonizer and the colonized. There's not really a question there.

But you're onto something aren't you? You certainly are.

Yeah, this is what your work has been making me think about.

I think there are two things with that: the interest in forced clan destination probably does come from thinking about the kind of bargains that you cut, and there are the invitations to self-betrayal, which includes betrayal of your history, betrayal of your ancestral struggle, and betrayal of your peers. That's certainly something that I'm thinking about with this. What you were saying in terms of Ireland as a colonized, a settler colony, but also the agent of, certainly in a really extensive way, religious imperialism. We tend to be a bit less keen to discuss.

Then secondly, the assistance to the extension of, and the aiding of, for example, US imperialism. We are a colonized nation that aids in the colonization of others and has learned nothing. In terms of what that has to do with being non-binary, maybe there's something very kind of simple in terms of creating a narrative film where there are no goodies or baddies. Why is Ireland so keen to discuss its victimhood in relation to colonization and so shy of or even in denial of how it perpetuated it? Part of it is because narrative framing doesn't allow you the complexity to have both, and that's also the case in lots of other kinds of categories.