Emotional Haircut

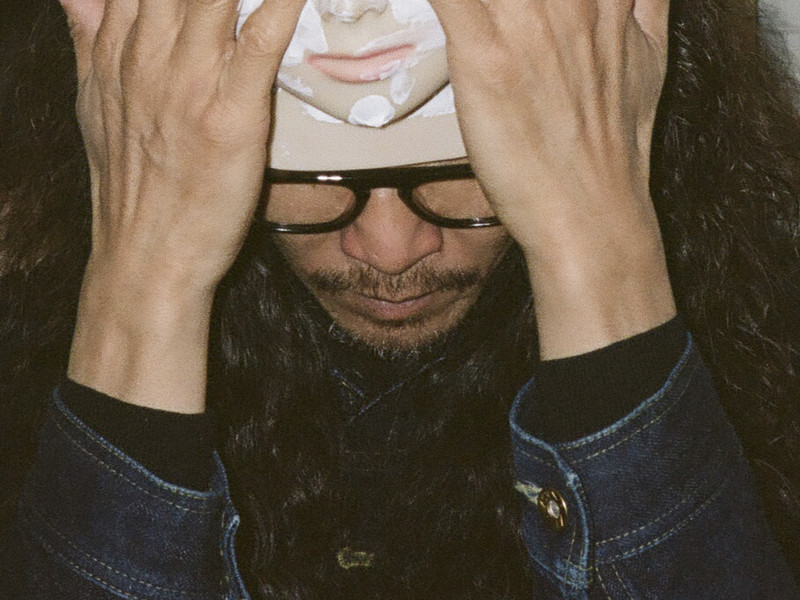

By 17, Elliott had relocated to Texas for cosmetology school, and soon after, got invited to assist at a Proenza Schouler NYFW show. That brief visit introduced him to the city’s fashion crowd and the thriving LGBTQ+ community he saw in New York.

Since moving here, he’s worked backstage for brands like Vaquera, Hardeman and Namilia, and earned a permanent space working at Hairstory Studio, focusing on the people who’ve always faced rejection in the world of beauty because of their gender identity, race or hair texture. “[People with curly or kinky hair] have been traumatized the most in this industry,” he says, “but I started targeting these textures because I was in the same realm and I’ve been traumatized with so many bad haircuts throughout my life, too.”

For Elliott, giving proper attention to the beauty industry’s traditional outcasts doesn’t only mean working with them—it means using his voice to educate other people about their lives and trials. “I’m not doing hair to get famous—I’m doing hair to listen to unheard voices and people who aren’t given a platform, and to execute what I think is morally and ethically correct, which is radical inclusion.”

How did you originally get into hairdressing?

It piqued my interest when I was 15—that’s when I moved to Germany, and that was my first step into streetwear and seeing fashion firsthand. Germans are very expressive with their outer selves.

And it wasn’t like that in Hawaii?

No, it was a complete culture shock. Hawaii is very low maintenance, and mostly everybody is living in poverty. So, the importance of visual self-care or visual expression isn’t thought highly of. In fact, you’ll probably be judged for being overtly expressive with your hair, makeup or clothing—it’s a conservative mindset. Whereas Germany was the complete opposite.

What else did moving to Europe expose you to?

Being raised in Hawaii, my family was one of 10 white families in the neighborhood until the end of the ’90s. So, traveling abroad and learning about America and aristocratic Europe, learning about different ideologies and history, I learned that everybody needs to listen. But as a white man, if people are going to listen to me because of my skin color—which is not relevant to me, but it’s relevant to other people—if I have this ‘power,’ I need to speak out about things that are actually important, as far as humanity goes. It’s an unchosen platform that people tend to not utilize because of white comfort, and I never felt that growing up. White privilege is not a thing in Hawaii—you’re seen as a minority. So, coming to the mainland and Europe, where I was not a minority, I realized, ‘Okay, the minorities need to be heard.’ White minorities—that’s self-affliction. You colonized a place, so you probably shouldn’t live there. But as far as everyone else in the world, their voices are valid. So, I really started to value the importance of learning history about land and people, suppressed people, culture, activism and women’s rights.

Is there a beauty industry at all in Hawaii?

I think commercially, for the outside viewer—the people who take holiday there or foreign people who are looking to buy homes there—but as far as local people in Hawaii, not so much. There’s traditional hairstyles, leis, or if a girl wears a flower in her hair, what that signifies. But those things are only taught about because they were oppressed. Those traditional things are not spoken of daily or commercialized.

What inspires your approach to hair?

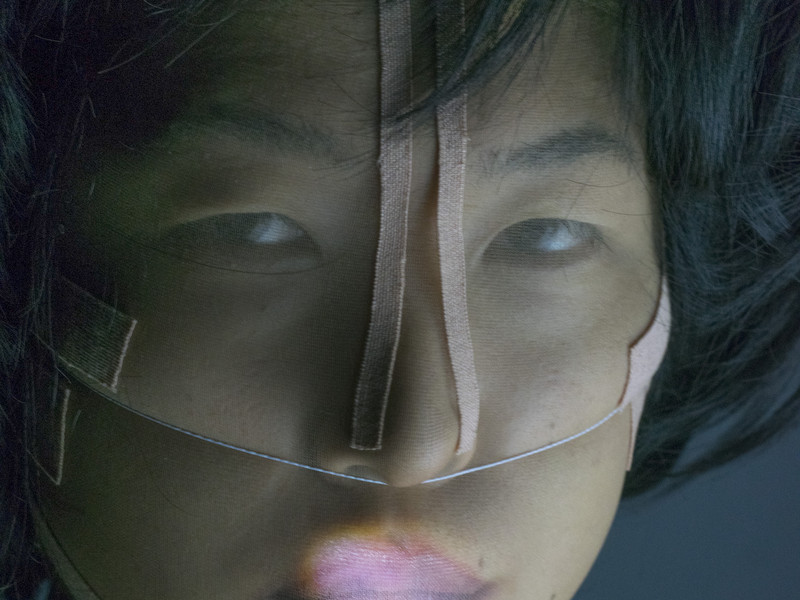

What influences me the most is really the fucked-up hair. Like, the inverted roots and fucked up bob from The Fifth Element. Walking around Soho and the Lower East Side, looking at these roughed-up kids—they have amazing inspiration. It all goes back to rebellion and protesting unconventional beauty. Shaved lines in a long haircut. There are a lot of amazing ideas for looks that stylists will tell you are not possible, but they are—you just have to try it.

What’s your favorite kind of hair to work on?

Wavy, curly, kinky, soft—all kinds of textures in that realm. We’ve been told, ‘You can’t have bangs because your hair is curly,’ or ‘This product wasn’t made for you.’ So, I wanted to hone in on that ignored realm of the spectrum. In Hawaii, almost everyone has curly hair—Polynesians, Micronesians, Melanesians—most of the residents have wavy, curly sun-bleached hair that we call ‘Ehu curls,’ which refers to a tight, frizzy curl.

What do you look for in the designers you choose to work with?

Definitely inclusivity. There needs to be more than one kind of token POC—it needs to be fluid and open and a safe space for non-binary, non-gender conforming or trans models. Those are the people of my community who are the clients in the corner. They’re not usually seen as a priority. So, I make it my priority to elevate these people. It’s the brands who are working with them that I find interesting. I like working with young kids who are shunned by their communities but are living, bright human beings.

To that end, you’re also an activist. Does your activism intersect with your work?

As far as activism colliding into my everyday life with clientele, it always does. People always ask me where I’m from and it goes back to me explaining my childhood in Hawaii, and to privilege and non-privilege, and hearing other people’s stances, especially here in New York. I’ve met so many amazing people who have endured lots of rejection—women of color who go into salons and the stylists telling them they can’t have fringe because they have curly hair, or trans men and women going into spaces and being misgendered.

Anti-semitism also comes up all the time now that I know I’m Jewish and I’m learning the history of my people. It’s been really interesting meeting so many different afflicted people throughout society and the beauty industry. Straightening processes, keratin, relaxers, being told your curls are messy and need to be tamed—we’re people, we don’t need to be tamed. We need to express ourselves. It’s vital to our mental health and our human existence. If we don’t express ourselves, we become monotone and silent, and that’s when evil takes over, like fascism or dictators.

What have you found difficult about working in beauty?

What comes to mind is how opportunist this industry really is, and how quick someone will talk to you and use you when you’re needed in that moment, but the minute you’re not, it’s like, poof. My views are so personal and interconnected that I don’t work like that. So, that’s when it becomes conflicting. But you deal with the bullshit and you move on.

Right, the prospect of fame can make it an ugly industry.

Yeah, and I have no interest in being a part of this popularity contest—it’s not about that for me. It’s about listening to people, and learning about people, and [having] compassion, and what life is actually about—the importance of community.

How do you bring your ideals to your craft?

I like to encourage people to embrace their natural look. No matter your length or texture, hair is just hair. I like to go with what naturally happens and I don’t like to overdress hair. When people overly blowdry, straighten, or round-brush a haircut, and then finish with an iron, they’re probably hiding something. So, I was taught in this ethos of working with the natural texture. I like to show people how the haircut is going to live, and show them how to naturally air dry perfectly. That’s a true gift. Instead of teaching someone how to manipulate themself to society’s standards, no—manipulate your haircut to how you want it to live on you.

How have you seen this encouragement affect your clients?

I think it makes people more confident within themselves, and that teaches others who look like them to be more confident. It’s the all-natural movement—girls not relaxing their hair, cutting off their damaged ends and growing their afros. That’s an iconic and important movement. These things have been suppressed by society because it’s different and people don’t understand that.

What does it mean to you having a hand in someone else’s look?

It means that I have a purpose. Doing hair has given me the capacity to talk to anyone. It’s taught me how to be confident in myself and how to turn insecurities into values. Every appointment is like a hair prescription. Everyone has a different background and texture. I’m constantly listening to these things and executing them in a self-caring way. It’s not a hair factory—it’s a person-to-person undivided attention moment.

Follow @officebeautynyc for more on our favorite hair stylists, makeup artists and product reviews from our office Beauty Committee.