Eunnam Hong's Souvenirs

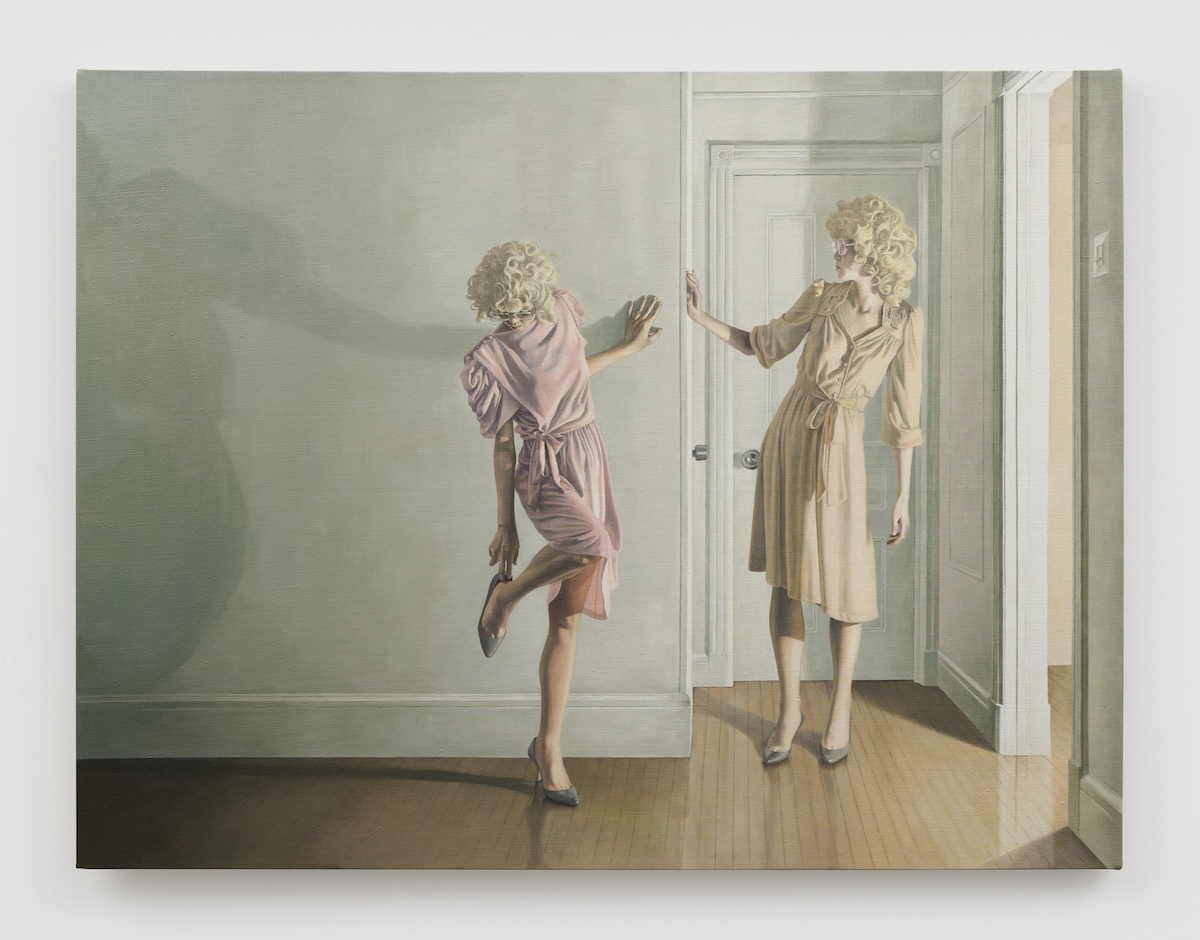

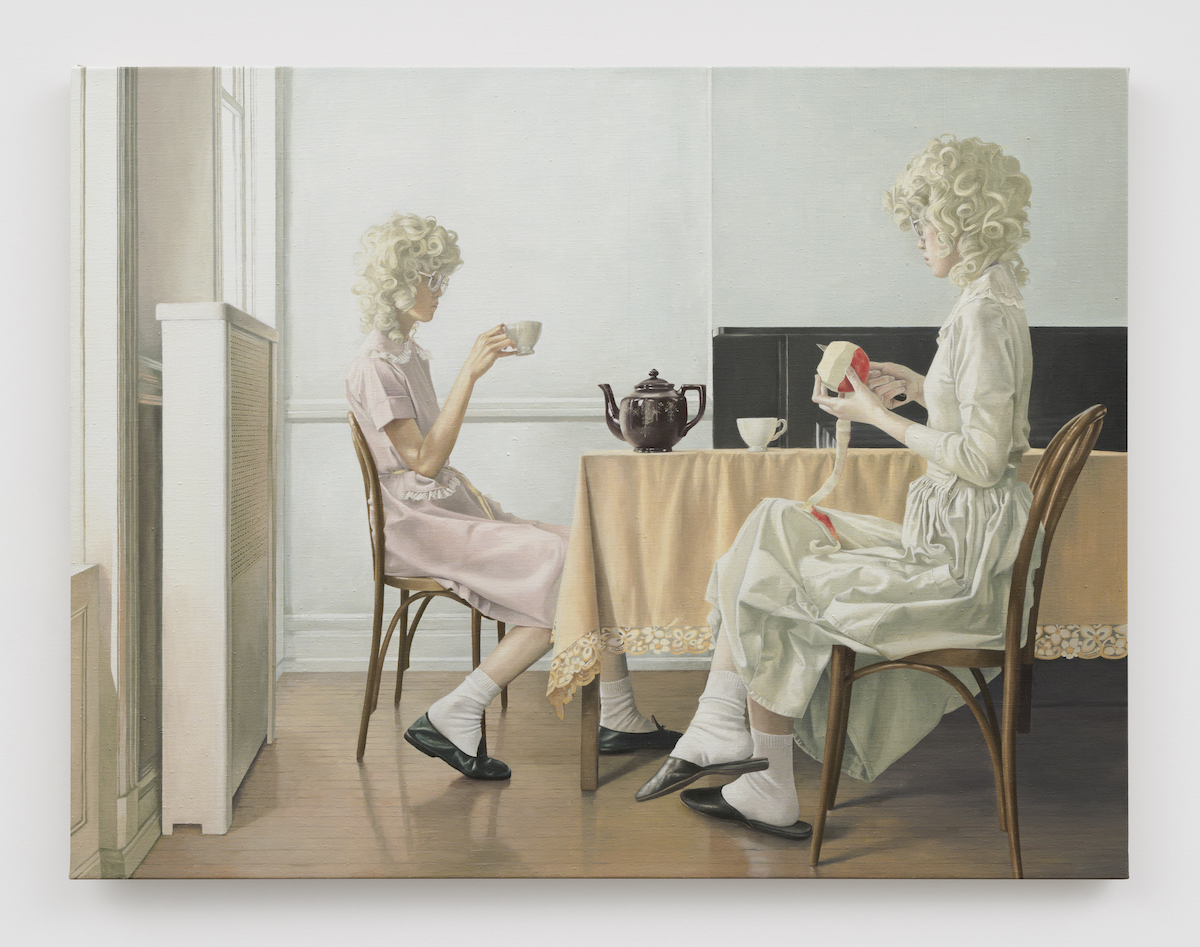

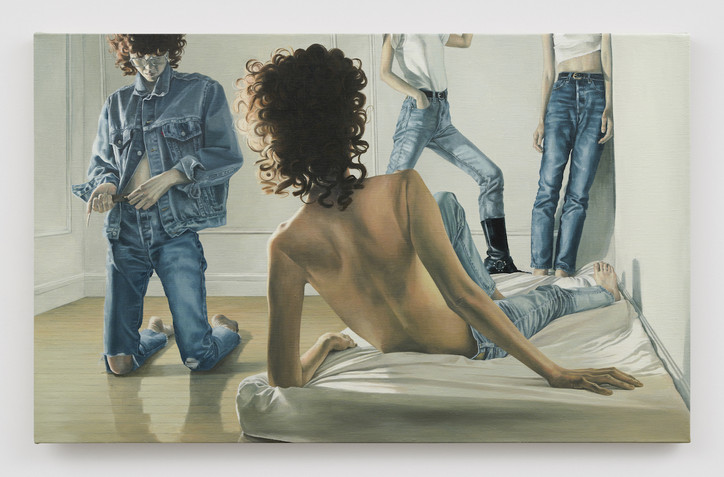

The images are as observational and detailed as the rooms depicted by Edward Hopper. Hong’s paintings are layered, but they are at arms-length of the impasto intrusion of an audience. They look alien and teeter on the border between a sci-fi conception and a political designation. They stick to the linen canvas, the figures held in muffled spaces, soft, thin and white like polished marble. They sit still with hardly a hint of direction (except for possibly a slippery floor leading to a sliding heel or the safety hazard of an extension cord leading to a scuffed chin). The paint lies almost behind the grain of the canvas, and there is barely a visible brushstroke. Compared to the directional brushstrokes of, say, Rembrandt, the image could lie flat. But Hong, like Rembrandt, has a love of textures. Although she expresses this love through the dressing of the figures (rather than the material), her clones slip into a stylish whiplash of time and tone. Rose jackets reflect light from a flaring open door. Meanwhile, a belted jacket dress sits in the shadows with a boxed shoulder, black leggings, and zig-zagging arm folds the color of red velvet drapery.

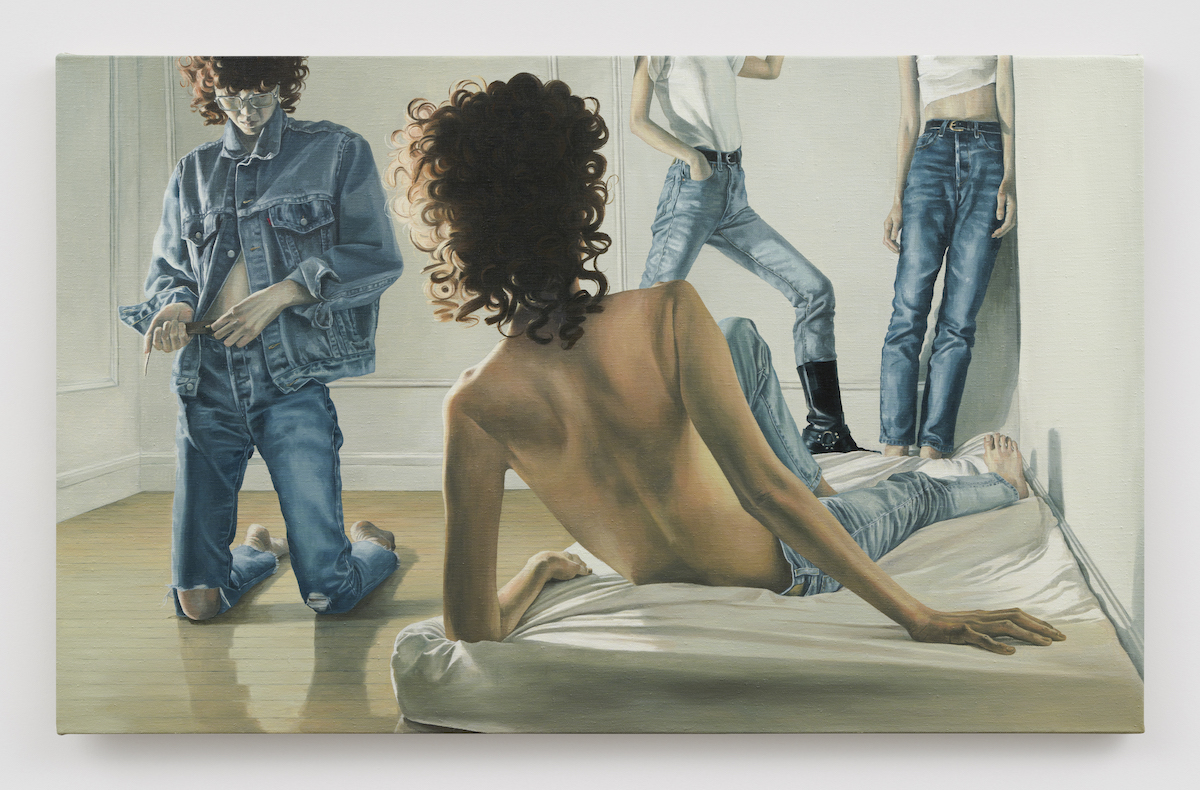

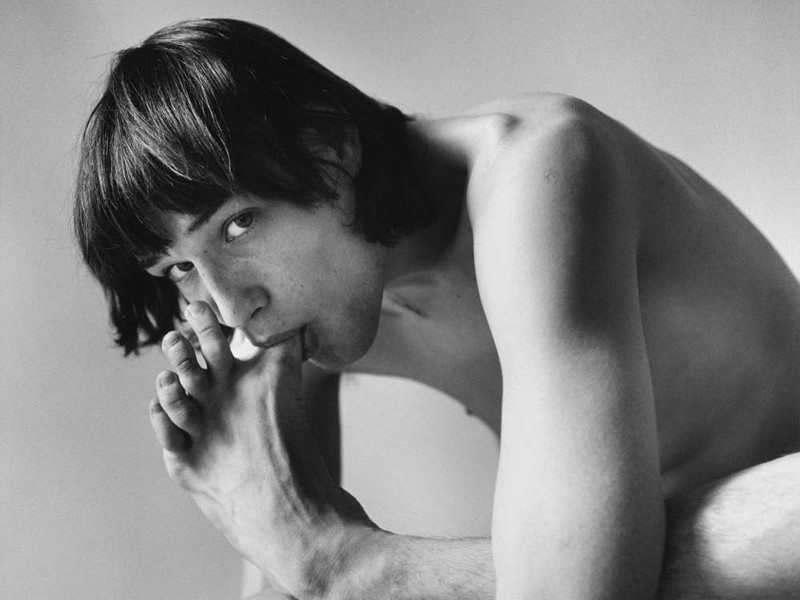

Jean Jacket, 2023

In all but one of the paintings, Hong’s clones adorn a blond wig that is voluminous, curly, sinuous and unusually white. (It references Bridgette Li’s ‘Woman in a Blonde Wig’ in the movie Chungking Express (1994).) The paleness and cool tones in most of the series push an eerie emptiness from the characters; they are emotionless, wigged and dressed nearly identically like mannequins. There are hardly any props in the vignettes, a teapot, a bed and an odd table or chairs. The scenes are not empty but bare in a late-90s sensibility that one could see in a commercial or editorial campaign. Prada’s Fall 1998 Campaign, shot by Norbert Schoener, was lit similarly, and the model (Angela Lindvall) was captured at the same lower angles as the viewpoints painted here. If the paintings were hung lower in the exhibition, the audience would likely feel like voyeurs or children, peeping into an uninvited scene with stone-eyed figures that hardly notice your existence and are indifferent to their own. Instead, they sit at eye level and confront the standing viewer like a phantom, anesthetized and hardly there. Hong tells a story through hollow robes. But they aren’t hollow, are they?

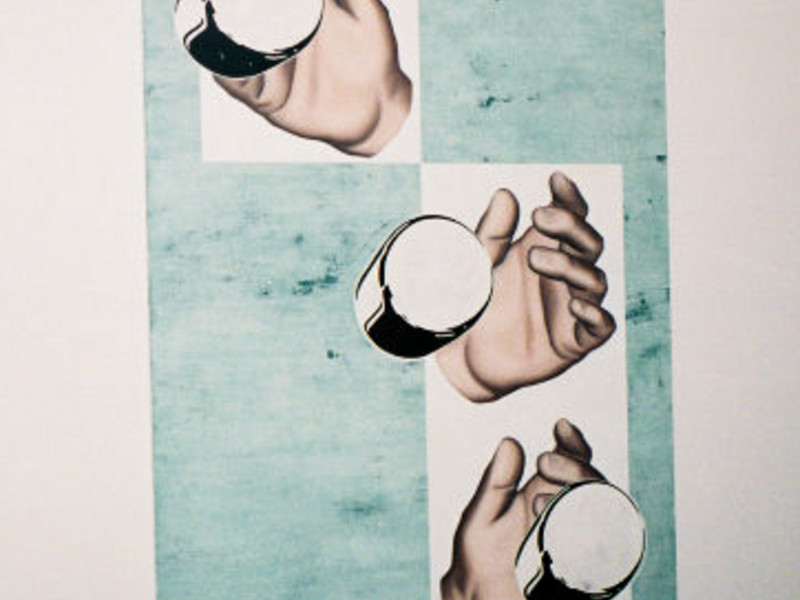

The numbed blue box-pleated skirt speaks to the corduroy shirt. The notched collars skittle down to short sleeves or ballooning cuffs, and the tied boot and smoking Malboros haze over the military green pants and their frayed hems. There is a requirement of mystery in art, one that either questions, berates, or assuages, or one that simply makes you stop. That is where the souvenir comes into play. The souvenir is an indicator, an image, an empty jar. A time marker in the visual fabric of our lives. Sure, the jar tells a story, but it is not whole. Its content is lost in the experience of another, and the viewer is faced with the choice of either looking at the facade or going deeper. Hong’s work doesn’t openly speak to the audience with a siren of symbols. The paintings talk to themselves from within the image, but you can’t hear it. As much as we are left on the outside, having not experienced the story behind the souvenir, there is still a story to be read. Under the wig and between the tentative gestures of these figures, there may not be a straight message to hear, but there's still that hum that comes from somewhere. All there is left to do is imagine.