Even Mike Pence Fucks

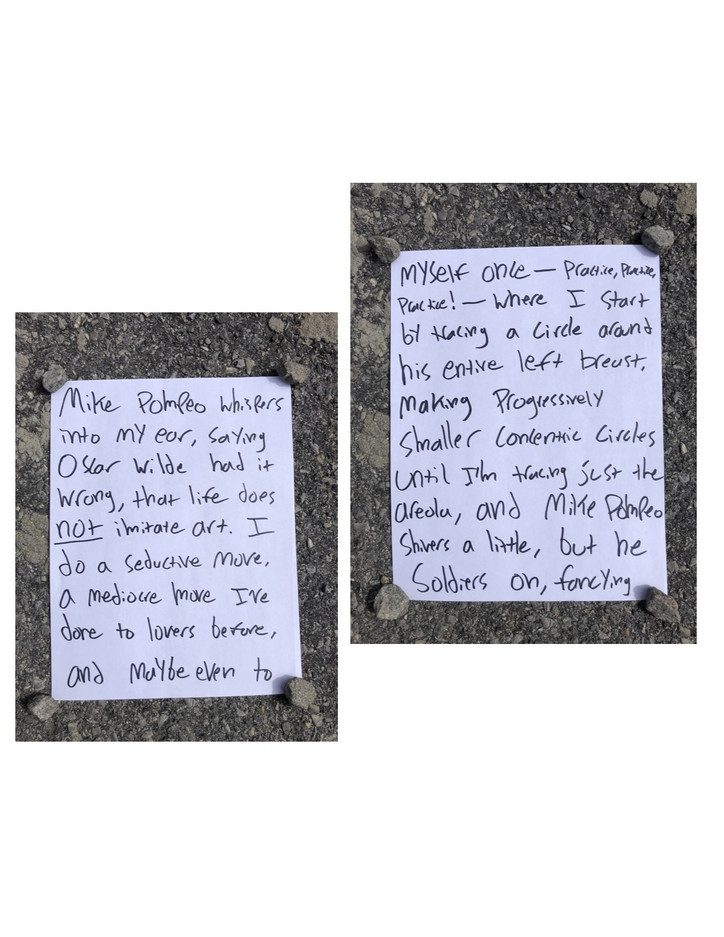

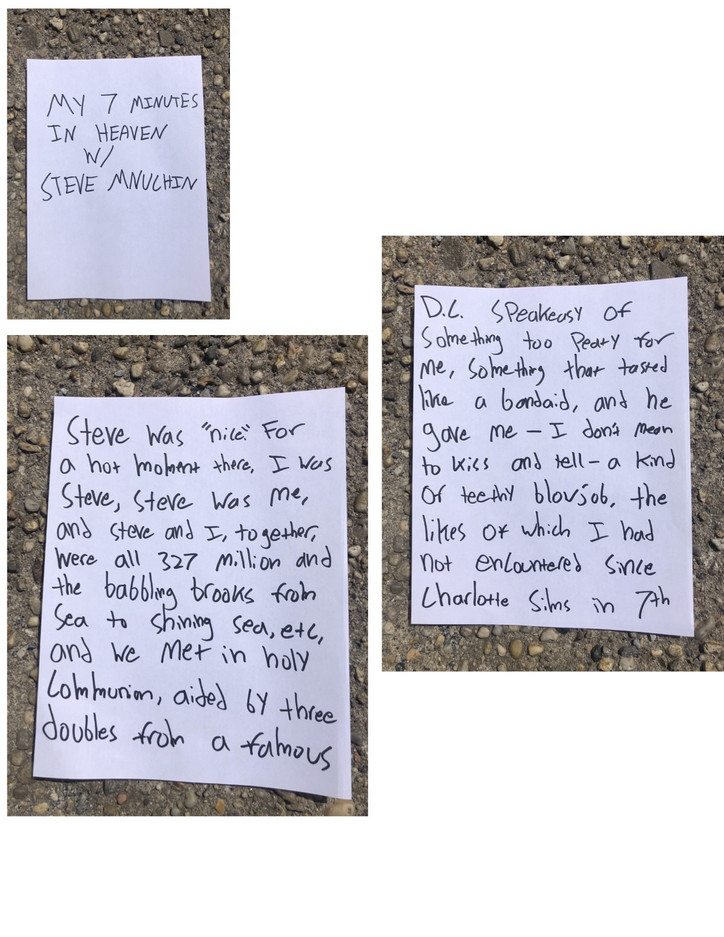

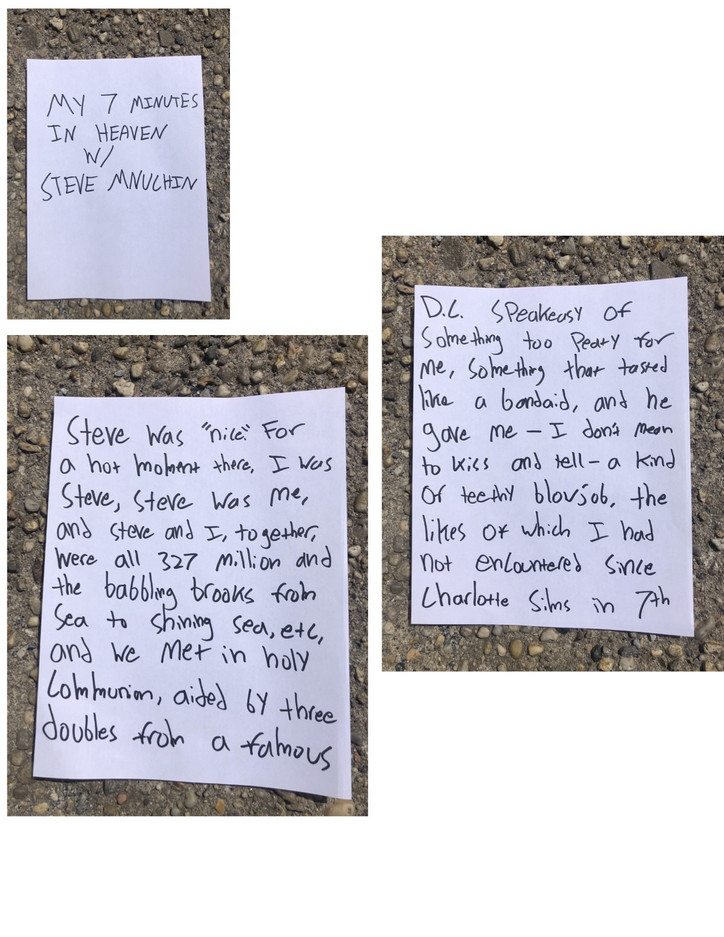

Read Gideon's two poems, "Mike Pompeo's Nipples" and "My 7 Minutes in Heaven with Steve Mnuchin," below.

Stay informed on our latest news!

Read Gideon's two poems, "Mike Pompeo's Nipples" and "My 7 Minutes in Heaven with Steve Mnuchin," below.

Friday. 3 pm. This is luxury. Friends is on the hotel TV. I’m eating a burger in bed. New York is far behind me. My only worries are the possibly-infected cut on my finger and whether or not wearing my flea market “LADY RIDER” leather vest would make me look like a poser. At the festival, the Veterans Park bartenders know us all intimately. When people tipsily fumble with inserting their credit cards, the bartenders joke about sticking things in the wrong hole. I get my favorite flavor of Smirnoff Ice (that my deli doesn’t even carry). The bartender doesn’t say goodbye — she says “see you later.”

The buffest guy here is worried about getting bloated. “No more lemonade for me,” he resolves. TV got it all wrong about bikers. In any situation, I’d rather go to a biker than a cop. Priscilla Block sings and makes me realize that country songs and my cosmopolitan party-poetry aren’t really that different — we both write about drinking and running into exes. Maybe country music is my fate. Priscilla chats it up with her fans: “I see your wrist. Did you get my signature tattooed on you? I don’t even know if I love my dog that much.”

5 pm. There’s a Zyn tent in the middle of the park. “What the fuck are Zyns?” I hear someone ask. We both turn around to see the line wrap around the tent twice. It’s still light out and one of the Nitro Circus guys is flying off a ramp while seated in a recliner. “Give it up for Tyler Roberts, who is lying on the ground because he just jumped a couch.”

8 pm. HARDY gets real American. “If you’re in this country and you’re not proud of it, FUCK YOU!” Everyone’s booing these hypothetical anti-patriots. I find myself clenching my Smirnoff Ice amidst an emblazoned crowd chanting “USA! USA!” People notice me not chanting. I keep my eyes to the ground and wait for the country music to start.

I’m wondering if I should’ve done pushups in the hotel room when I hear someone behind me ask, “Have you ever been in a mosh pit?” Some kid whose age is definitely still in the single digits answered: “Once.” A girl finds a motorcycle-shaped chip in her bag. Her mom reacts in a way that reminds me of the grilled Cheesus scene from Glee. She claims the Harley chip is a sign from god. The girl eats it without hesitation. Someone hops the fence from GA into VIP. For the first time since that chant we all share a single look of solidarity — a look of ‘I don’t know what the fuck that was but it’s not my business.’

Jelly Roll is on. “God bless America. God bless Milwaukee. God bless the long-haired sons of sinners.” God bless my dead camera. He dedicates his song to “those who tear it down Saturday but still end up in the pews on Sunday.” I think of when I’d leave the club at 3 and end up at my 9 am literature class the next day. “This is for those who love Jesus but still say ‘fuck’ a lot,” says Jelly. He believes that the spirit of rock and roll is with us, here at the Harley Davidson Homecoming. “The spirit of country music is here. The spirit of love is here. God is in Milwaukee. Heaven has a smoking section and an open bar.” A Ziplock bag containing cheese curds and a joint is launched to the stage. It’s an impressive throw. I definitely should’ve done pushups before coming. Jelly gives his ode to weed: “I was only 12 years old when I thought I smelled a skunk in my house. I now know that to be the smell of freedom.”

10 pm. In front of me is a heated argument about spots being stolen. One thing I learned — first from a Patti Smith show earlier this year, then from the Jelly Roll show — don’t mess with middle-aged women’s concert spots. Amidst the arguing, one of the antagonized men turns around to ask me, “Are you here all by your lonesome?” I can barely answer because I’m still shaken from hearing the phrase ‘all by your lonesome’ unironically. His friend turns around to call me cute and ask me for my Snapchat. I haven’t used Snapchat since I was in high school (in Ohio). I’m taken aback because I thought that only girls like Sabrina Carpenter were considered cute in the Midwest.

Machine Gun Kelly rides onstage (in an HD Low Rider ST. Very nice). All weekend, there had been murmurs about his surprise performance of his new song with Jelly. God doesn’t bless my dead camera so I don’t get any pictures of him. Jelly and Kelly debut their song and Kells sings with his emo voice. Jelly thanks the crowd: “You guys took the most average, overweight, white trash guy in America and made him a star.” Jelly shouts out his guitarist — it’s apparently his 57th birthday. “He’s the only person onstage with a good credit score.” Considering all my apartment applications that just got denied, I can’t say the same. “He’s also always the drunkest person onstage.” I find common ground.

The older couple next to me taps my shoulder: “You’re young. Who’s that young, skinny fellow next to Jelly?”

“That’s Machine Gun Kelly.”

“And who’s that MGK that Jelly keeps talking about?”

“They’re the same guy — MGK is just his initials.”

“Oh! He’s quite good. He should be famous.”

A six-year-old boy tears a beer can in half. The burly guy in front of me is wearing a tail. America the beautiful.

Saturday. 12pm. I haven’t taken my meds yet so I’ll take them with some free brisket and an alcoholic beverage like America’s god intended. I ask the bartender if it’s too early for a Twisted Tea. “It’s never too early for a Twisted Tea,” they reply. Truer words have never been spoken.

I’m wearing my vest. Goddammit if I’m a poser. My mullet is wild and beautiful. My cut is definitely infected. While I’m watching the ride-ins, someone from the news tells me they love my look and asks for a photo of me with my bike. “Sorry, I didn’t actually ride here. I just dress like this.” I resolve to pay my loans, get my bike license, get a bike, and ride into next year’s Homecoming to redeem myself. I spend my time in between shows at Nitro Circus, high-fiving the bikers and wondering if I could even pull any of this off in Skate 3.

6 pm. “Welcome back to the party, motherfuckers!” Cypress Hill is on and I can’t tell if the big cloud of smoke is weed or a fog machine. Probably both. Weed isn’t legal in Milwaukee. Rock on, Harley Homecoming. Joint in hand, Sen Dog grants DJ Muggs the title of Greatest DJ In The World. And apologies to all my friends reading this, you guys do not compete for that title. “Are you feeling the vibes right now? Are you feeling alive right now? Are you feeling high right now?” asks B-Real. I make eye contact with Sen Dog on my way to do some shots with some bikers.

A photographer comes around and has Alex and Stu put me on their shoulders for a photo. Very few words are exchanged before I’m up in the air.

The Offspring comes on. “Milwaukee is a mecca to a beer drinker like me,” says Noodles. “Thanks for being here instead of the beer tent.” All 60,000 of us collectively regress to our pop-punk phases. I say ‘phase’ like it ever ended, but it’s 2024 and I am two-stepping in Doc Martens and holding a digital camera while they play “You’re Gonna Go Far, Kid.” Apparently that song just hit one billion streams. “We got like, 200 bucks from that,” says Noodles.

They debut their new song and Noodles tells us, “That is the best we’ve ever played that song. Dexter left it all out there. He really nailed parts of that song.” “Parts of songs are my specialty,” says Dexter. Noodles says something about getting turned on. “It’s like we have a choir of earthbound angels.” He’s talking about us. “Do you know why they’re earthbound? Because they’re a little bit naughty. This is an audience that loves their curse words. Would you guys like to sing and cuss with us?” Dexter says this audience is the best thing that happened to rock and roll.

9 pm. Red Hot Chili Peppers are here. This is the band that all my friends in bands want to be. They bring out Willie G, who’s nearing 50 years at Harley Davidson. Anthony Kiedis is in a cowboy hat. “Take off your shirt!” a man behind me yells. I turn to give them a nod of understanding. “He wants a husband,” his friend explains. Good luck, man. Beach balls are bouncing around. There is no hatred in the crowd right now. I’m content watching the stage through the neck rolls of the guy in front of me. There’s a guitar and bass solo that brings me to tears. Fireworks go off. No one notices. Many of us are listening with our eyes closed, tired and heat-stricken, but willing to bask in the light of Flea, jumping around in a skirt.

1 am. I end up meeting that guy from the night before. Do it for the plot. We did the things you do in the Midwest — drive to the gas station and buy hot food. We waste gas to keep the conversation going.

Sunday. 9 am. Waiting for my flight, there are two guys next to me at the gate who see me editing photos — they’re decked out in Harley merch and cowboy hats, I can only assume they’re coming from the festival. “HARDY was whacked out that night.” Oh yeah. Definitely coming from the festival.

Working alongside Bryn Silverman and a cast of other collaborators, Dennison illuminates the intention and legacy of Black people's ability to play with the legend of the wind.

Silverman, who calls the production of this project "shockingly smooth," spoke to the abundant donations of equipment, cast, and time that were contributed to the filming process.The local film community made it all possible. "We also just had a spirit of working with local Louisville filmmakers and crew. Everything was so community-driven, which made things a breeze, and we were just so supported," she says. The Black skate community of Louisville also welcomed the film and crew with open arms "It was really heartwarming to be welcomed into this community,” Silverman adds, “especially because I didn't grow up skating."

office sat down with Dennison to discuss the film's focus on sound production, jazz, and playing with spiritual knowledge as a means to begin.

Clarissa Brooks— I wanted to jump into something specific. There is a scene where all the members of the 502 Crew are lying down on the floor and are shot from above. What inspired that shot, and can you talk more about the intimacy of that moment?

Imani Dennison— I love this question. Also, I wanted to add that this film is about Louisville being a segregated city and still is. That trajectory and how Black people have been building community and having it ripped from them and also just navigating the segregated South — I mean, even today in 2024. As much as this film is about imagination, it is definitely about resistance, resilience, and overcoming structural racism in a segregated city and a small town, especially.

In choosing to have the 502 crew lay on the ground for their interview, I wanted them to feel comfortable, and I didn't like the interview to feel stiff. I'm not a fan of talking head style interviews; for theirs, I wanted them to feel their most comfortable and vulnerable, too. We know that connecting with the ground helps soothe anxiety and helps people ground into their bodies a little easier like having the ground have their back and having their brothers on each side felt appropriate.

It reminds me of the couple [Laneisha Beasley & Markice Armstrong Sr.] towards the end of the film whose shoes are off and are comfortable on the couch as they do their interview…

Yeah, that's the same concept: be on the couch, no stiff interviews when talking about why something is special to you. I wanted that couple to feel at home when communicating to the world about this community that they helped build and are also a part of. Having that intimacy felt important.

Are these folks that you've known for a long time, or have you built relationships with everyone throughout making this film?

I started an iteration of this project in 2020 when the pandemic hit, and I moved back home for eight months and got a small grant to make a film about my hometown. I made a 9-minute proof of concept of what we see today called The Roost. So, with some of the folks in the film, my initial contact was in 2020, but I loosely kept in touch and let them know I was still working on getting more funds, but Jordan [from the 502 crew] and I grew up in the same neighborhood, and even though we weren't close we knew of each for awhile. It's a very tight-knit community, and folks were really trusting, which is excellent because reception and trust are everything.

I would love to hear more about your rituals when you begin a project. What does it look like in your world?

Conceptually, when I have an idea in my head, in my body, or in my spirit, it usually starts with music. I make a playlist that narrates or guides me into images, so I start going online and sourcing images in my head, and I make a folder of them. Step one is always sound to me. I start thinking about that immediately, and I'm a wormhole type of person, so I'll be up at 4 am just looking up stuff. Sometimes, that process is lengthy, especially with documentaries. I usually follow more than leading, relinquishing control, and following wherever it takes me. I ask myself what I am trying to say and research those words and phrases as I go along. Research is a massive part of my practice, and with this work, I knew I had to focus on my hometown story, and I started asking myself, well, who am I? What were my rituals as a teenager? What do I want people to know about Kentucky and Louisville? A ritual for me as a teenager was roller skating every Friday. I wanted people to know about this community and how it makes people feel, and I tied it to folklore, in this case, The Flying Africans, because it has so many roots in how Black folks have survived through storytelling.

What role does your work at Black Science Fiction play in the sound production of this film?

BSF and just the ethos of Black experimentation significantly impacted the project, as they always do for me as a maker and storyteller in this process. Aquiles Navarro did the sound score for TPCF, and he's a band member of Irreversible Entanglements. I knew I wanted him to be a part of this project early on. He gets it. He's played a show for Black science fiction before, but I think the work of BSF pours into this project by playing with free jazz, improv, and just experimenting with sound. Sun Ra plays a big part in this; he's the Afrofuturist. He's definitely an inspiration, and even though the film is named after the story The People Could Fly, it's also a myth, and similarly, BSF is playing with mythology. It all exists in the same universe.

Keiyaa's song [I Want My Things] , someone who has also played at BSF a few times, and she is also just a musician that I admire. That song, in particular, is so much about the reclaiming of things, which was necessary at the end of this film; I honestly didn't want the movie to end with any other song but that one. It was so perfect and tied to everything that I was like whatever we have to do to get it, let's get this song. It's just so good for the film.

Laura Sofia Perez, a friend from Puerto Rico, did sound design, so she and Navarro collaborated to make the sonics of the film, one of the many ways that we pay homage to the diaspora.

Do you have a favorite scene in the film?

It's gonna be the scene "Imagination" for me. It's the scene where the Sun Ra song "Imagination" plays, and the 502 crew is just doing their thing. They have on these Jabbawockeez masks that they used to wear when they were teenagers. In post-production, our editors manipulated that scene for motion under my direction so it could feel chaotic. I wanted us to play with time along with having the rights to have Sun Rain the film. It just felt right to make that call.

When was the last time that you skated?

The last time I skated was actually when I filmed the film. We did have a camera operator who wasn't on skates, but for a lot of the things you see where the shot is on the wood, it was me on my camcorder and just on skates doing my best. I grew up skating so much, and it makes you brave and daring; it definitely awakens my inner child, and yeah I love it so much.

The People Could Fly debuts at BlackStar Film Festival on August 3rd at 8pm ET at the Kimmel Center in Philadelphia, PA.

The 13th installment of the festival will take place from August 1-4, centered at the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts in Philadelphia with additional screenings and events in the surrounding city. In true BlackStar tradition, the festival’s programming is designed to cultivate the community of artists, filmmakers, and audiences beyond the viewing experience, with panels, post-screening Q&As, and parties interspersed throughout the four days. The festival will also make the majority of the year’s films available to screen virtually. This year BlackStar will show 94 films ranging from shorts, features, documetaries, and more, representing filmmakers of color from 40 countries.

Ahead of this year's festival, office caught up with Maori Holmes about psychic tricks, the importance of cultivating a team, and how she scaled a personal project into a movement beyond her expectations. Read our conversation below.

Brook Aster— Thank you so much for taking the time for this conversation. To start, what drew you to film in your early life?

Maori Karmael Holmes— I was interested in a lot of different disciplines growing up, mostly dance, fashion, and some kind of visual art. I was always drawing. I got interested in photography in high school and at the same time, I was also really interested in history. I would read my social studies textbook over the summer, and be done and start reading Vanity Fair and Toni Morrison instead.

I was always interested in looking at history, and I didn't know what to do with that. I was a really good writer. I was interested in a lot, and over time film started feeling like a place that contained a bunch of those interests. It was a discipline that required all of the disciplines.

My mom dated a filmmaker when I was in high school, for all of high school. So we would go to film festivals, and I saw Sankofa and Daughters of the Dust and was really exposed to a lot at that time.

Ultimately, I made the decision to [pursue an MFA in filmmaking] at the time that I was working in journalism. I just thought, this isn't quite cutting it. I want to make these things visual. Film felt like the next step in that.

How did you shift into a more curatorial role? What were the first seeds for what would become BlackStar?

I was always really interested in curating as an idea, because curators were always so well dressed and seemed so interesting when I would go to museums or encounter them in other spaces. I went to Howard for undergrad, and worked on Homecoming and on Yard Fest, and that’s basically programming work. And I studied film history.

Sadly, when I got to graduate school, I had faculty that were not that supportive of my work, and were actually pretty dismissive of the things I was experimenting with. I'm a Taurus, and my personality, especially as a younger person, was such that I was like, well, fine, you don't like what I'm doing? I'm going to do something else. So I put together a film program in my first year of graduate school, of all of my classmates’ work, and people really liked it. There was something about putting this program together that worked for me. I started a graduate school film club in that same year, and then got invited to do some other programs. I realized I was having success doing this, maybe not as the maker that I’d thought, but still using film.

I went through with my degree, and then made a film that went on the festival circuit. At that point, I was applying for other grants and trying to make films. This was in the early 2000s, and I wasn't quite getting the success that I thought I should have right away. I was so young, I didn't really think about patience. I just thought, “I didn't get this grant, I can't make films.”

I wanted to recreate the experiences that I had with my [first] film on the road, which were really transformative. I had this idea to start the first festival that I worked on: Black Lily, the Festival for Women in Film and Music. And then later on, BlackStar came out of a similar desire. I had left Philly and gone to CalArts to do a second MFA. When I came back to Philly, I wanted to make sure that I was doing something in film. I started BlackStar that year as a project, thinking it was a one-time thing.

What catalyzed the first festival? And how did it go from a one-off to an annual event?

There were a lot of anniversaries of independence for different African and Caribbean countries, I was definitely thinking about Black August. It was this one-time celebration in my mind. And it just did really well that first year.

The first year was completely curated, there were no submissions, because I thought it was this one thing. But the way people came out, even that first year, from other cities around the world — people came from London and Berlin and Richmond and Detroit, they came from all over. We got plugged in Ebony. It was such a big deal that people were like, when is it happening again?

And I have to be quite honest, the first six or seven years, it always felt precarious, because we didn't have any money. But people would always ask, when is it happening again? So I'd be like, well, I guess we're doing this again.

LEFT: from Do You See Me dir. Walé Oyéjidé

RIGHT: from Dreams In Nightmares dir. Shatara Michelle Ford

What changed to make you feel like it wasn’t so precarious anymore?

It's still precarious. It's just precarious at a different scale now. From 2012 to 2018, the festival was a project that I did on the side of full-time work. I was working at a foundation during the day. Then there were a couple of years where I was freelancing, then I was working at a museum, then I was working for another nonprofit. BlackStar almost fell apart in 2018 because I was focused on that last job.

I had to make a decision to take it seriously, or let it go. I decided to double down and take it seriously. I did not pursue getting another full time job publicly — I did have to get other work — but I was able to get a really beautiful consultancy in 2019, and that enabled me to project publicly that Blackstar was full time.

That was really just a psychic trick. It's not that I was spending any more time on it than I had before. BlackStar was and still is my entire life, it’s all of my vacations, all of my evenings, my weekends, all of that time. But because funders could meet with me during the day, and I was at conferences, I think it appeared as a different operation.

And to be transparent, someone pulled me to the side and said, “Philanthropy is not going to fund a festival, they're going to fund an organization. So you have to start talking about yourself as an organization that does this festival as one of its programs.” And I thought of all of these things that had been burgeoning, like the journal, the seminar, the lab, these other programs we had been thinking about.

In 2019, a funder had given us two years of funding upfront. I took that second year and hired myself a development consultant and an administrator for the first time. No one had a set fee before. Prior, whatever money we had raised for the festival to pay for everything, whatever was left over, we would split amongst the staff. No one knew what they were making. Everything was just basically for the love. It wasn't exactly volunteering, but it definitely was not a job for anyone.

Having that focused attention shifted what we were able to raise. That gamble of spending that second year on the staff doubled itself, we doubled our budget. So then I hired people in 2020. For the first time, we had a full time staff. We hired five of us. We were still making low salaries, but everyone committed, and then we doubled that number.

If you invest in people, then other resources will come. In 2020, we launched with five, and now we're at 21 people on full-time staff. And these programs have been more fully realized over the last four years.

How have you seen the impact of BlackStar manifested in the world?

I don't know that I have always logged it. We've definitely seen other festivals quite literally mimic our design choices from year to year.

In 2020, we had the benefit of happening late in the festival calendar. If you imagine the global festival calendar, depending on when you want to start the year, you could say it starts in September with Toronto and ends in May with Cannes, or you could say it starts in May. However you want to look at the year, but August is never a part of the equation.

At the beginning of COVID [in March], which was near the end of that cycle, so many festivals had canceled. We had the benefit of getting to learn and sort of study what was going on, and think about the platform and what we wanted to do. We ended up being incredibly successful that year.

I think that Black and Brown folks, we've been anticipating the apocalypse in many ways. We were kind of primed to continue, to live, to survive. People started to learn about BlackStar, who didn't know about it — before, we had a cult following. To have more people learn about us, with 3 million participants in 2020, it was really incredible.

One of the things that we did in 2020 was incorporate a talk show because we wanted to bring some a familial vibe while people were at home, and then we noticed that other festivals incorporated talk shows into their program the next year. So that's one other form of impact.

There have definitely been folks whose careers emerge in tandem with BlackStar. A lot of people who are working now had their first film or their second film with us. I can't say we can take credit for that. I often think of us as taste makers, we're at the vanguard, seeing the talent ahead of time. And we're also definitely a place for any filmmaker that is thinking about also working in the art world. That's like our special, special space.

I think someone else would probably be able to answer what you're really asking, because I'm sometimes just too in it. I have gut responses to things, but I don't know that I have a real bird's eye view to answer that.

LEFT: from What Channel is Love? dir. Michael Donte

RIGHT: from Enmity Djinn dir. Mohamed Echkouna

There is a really beautiful humility in that answer, and I totally understand feeling too close to it to view it in totality. Are there any films from this year's festival that you are particularly excited about? Or that, you know, you, you had a special moment with?

I feel like my answer is limited in scope, because I don't work on the film program anymore, which is a new development. That said, I'm working my way through the program.

One that I'm really excited about just on a personal level is by Madeleine Hunt-Ehrlich, The Ballad of Suzanne Cesaire. I think the film on so many levels is emblematic of what BlackStar’s foundations are. Thinking about how the film was made, thinking about how Madeline is moving in between the art world and the film world — Madeleine worked on the festival once just for one summer and has shown a lot of work with us. So that's gonna be a really special moment for all those reasons.

Another film that I have to say is really special is by one of my best friends — I'm excited for her, it's her very first film — and that's Yaba Blay's The Whites of Our Eyes. It's a short doc. She’s seen and been a part of so much — she actually named the festival, and so to see her have a film in it is really heartwarming, so beautiful and very, very full circle.

Our opening night film, Shatara Michelle Ford's Dreams In Nightmares also feels truly special. We had Shatara’s previous world premiere back in 2019. With this film, it’s a big deal that we have the world premiere and it didn't go to Sundance or Toronto. We're really holding that care that Shatara is exhibiting with us, and it's a mutual relationship, I hope.

I think the film itself is so sharp. The complexity of queer relationships and chosen families that it's showing, it makes me think about alternative ways of being. The staff at BlackStar, in addition to the work that we're doing in the world, we have been trying to make the work of working be part of it as well. Taking care of the team too is part of our mission.

We have this incredible team of Black, Brown and Indigenous folks, and the number of people that were like, “oh, this was on my vision board” or “I manifested this” when they got the job — it just makes me so happy. And in this political moment, to have a team that is very clear in our politics is also incredible.

There’s that TikTok trend about “Black jobs,” and I saw that and I was just like, we kind of have created a Black job. It's amazing, and I don't take it for granted.

The 13th BlackStar Film Festival will take place from August 1-4, 2024 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Get your passes here.