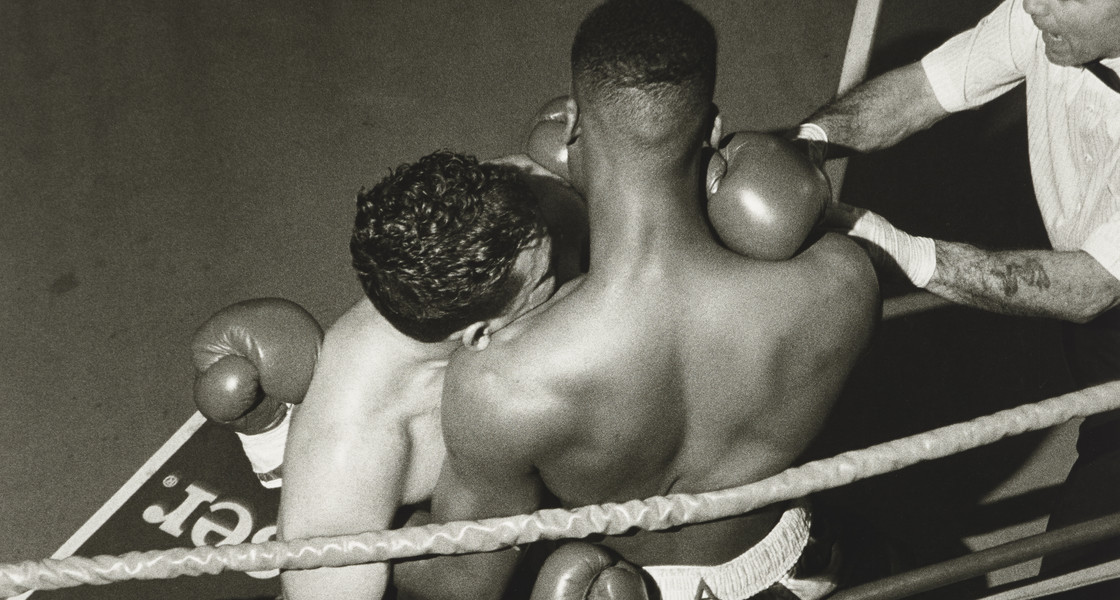

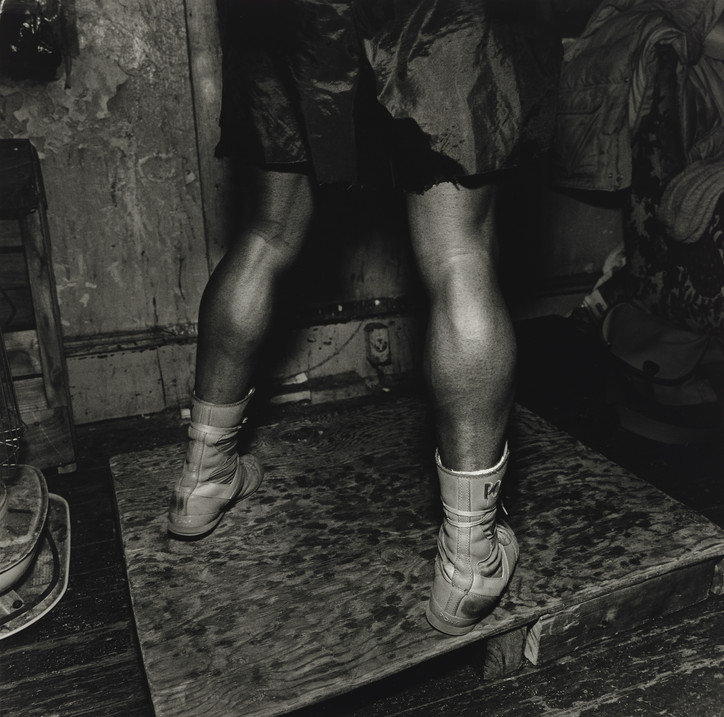

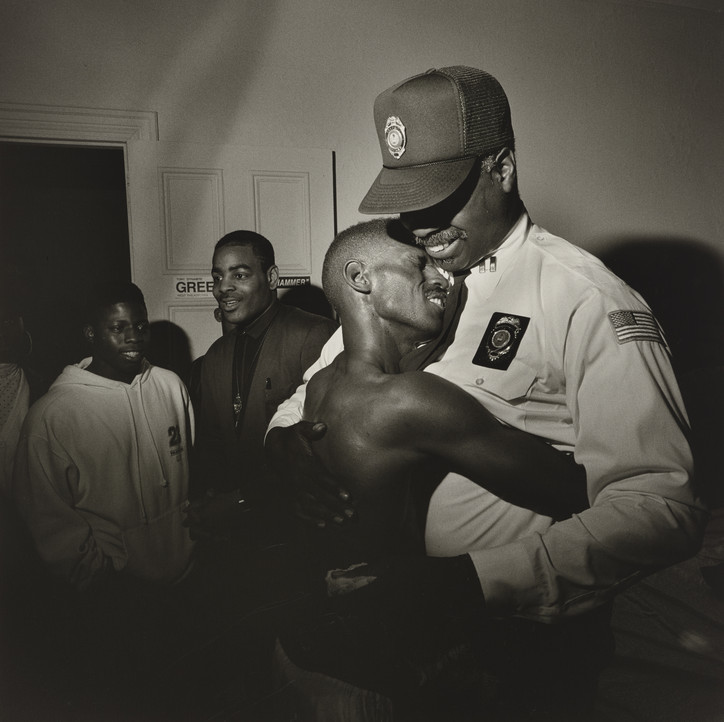

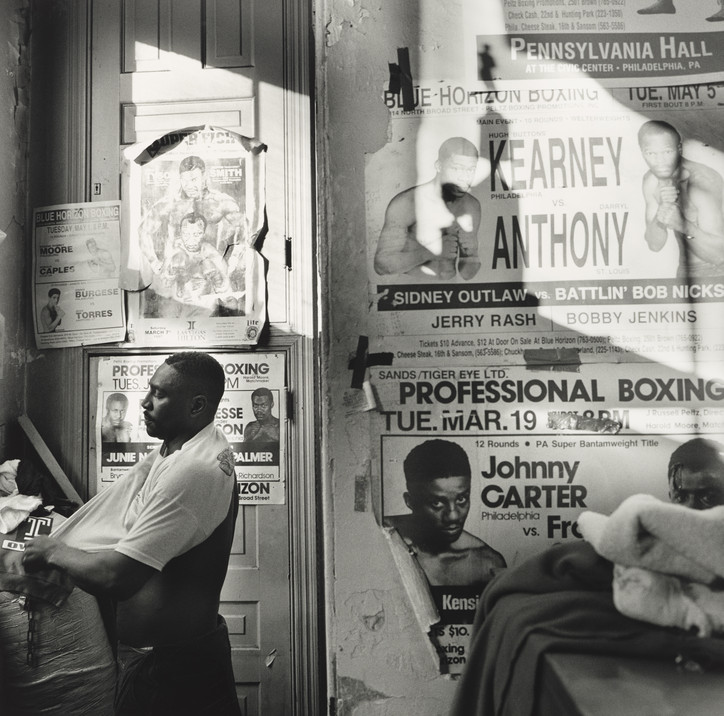

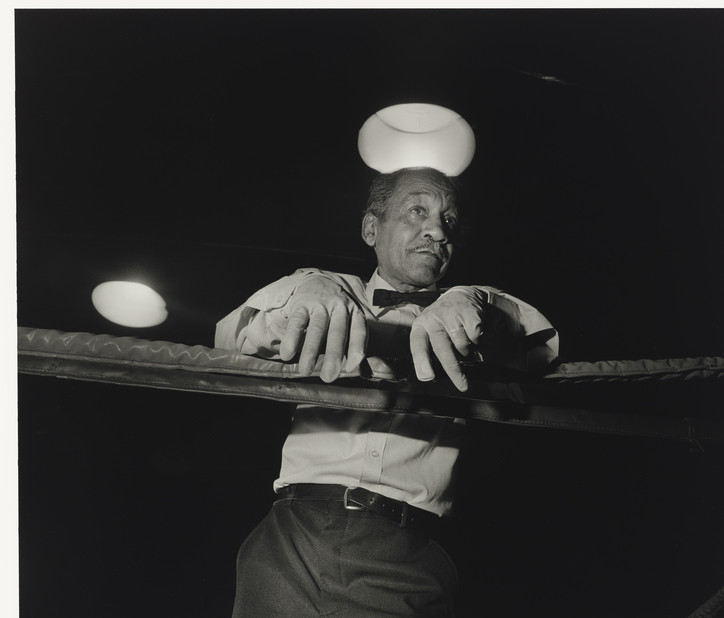

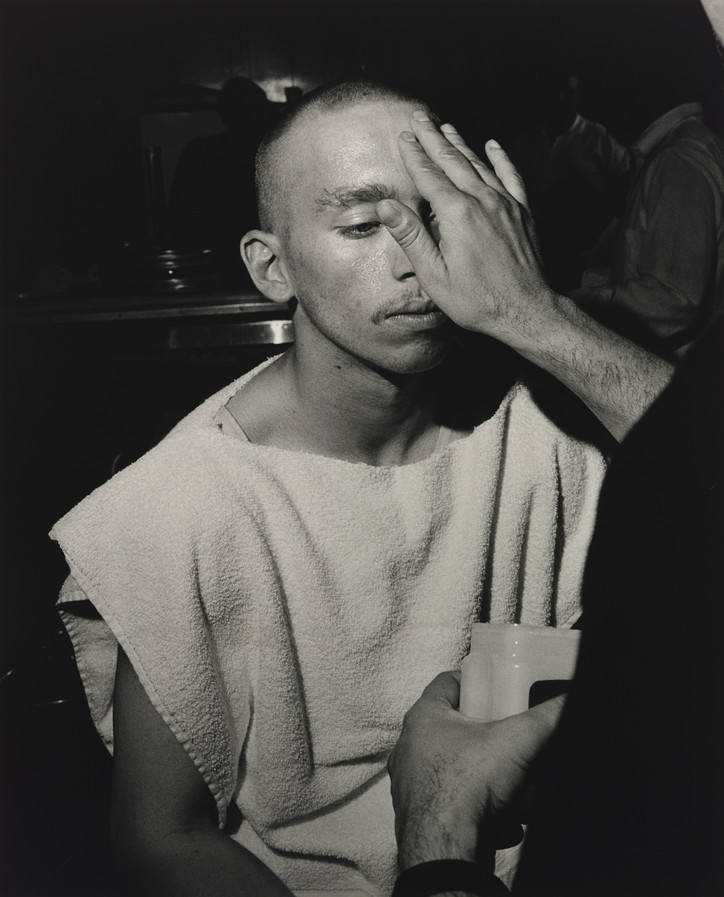

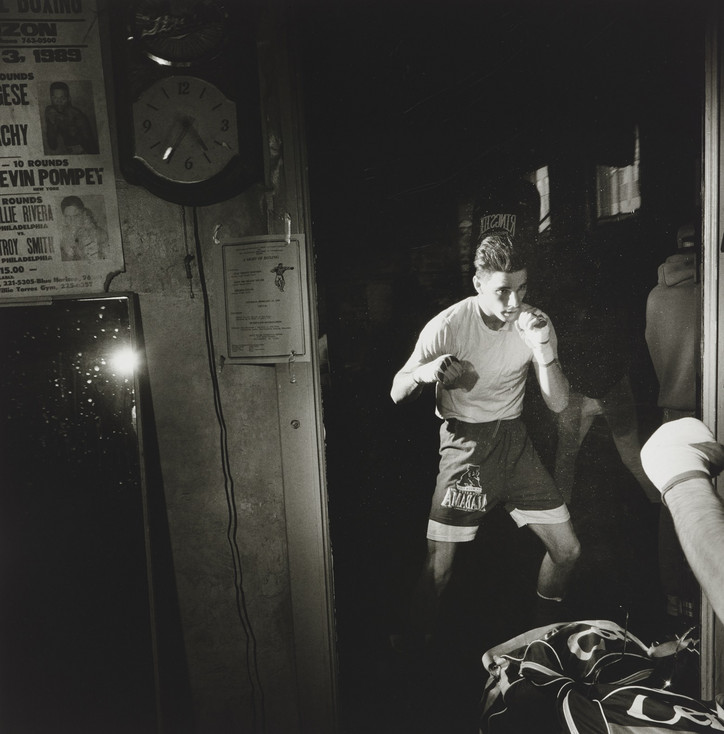

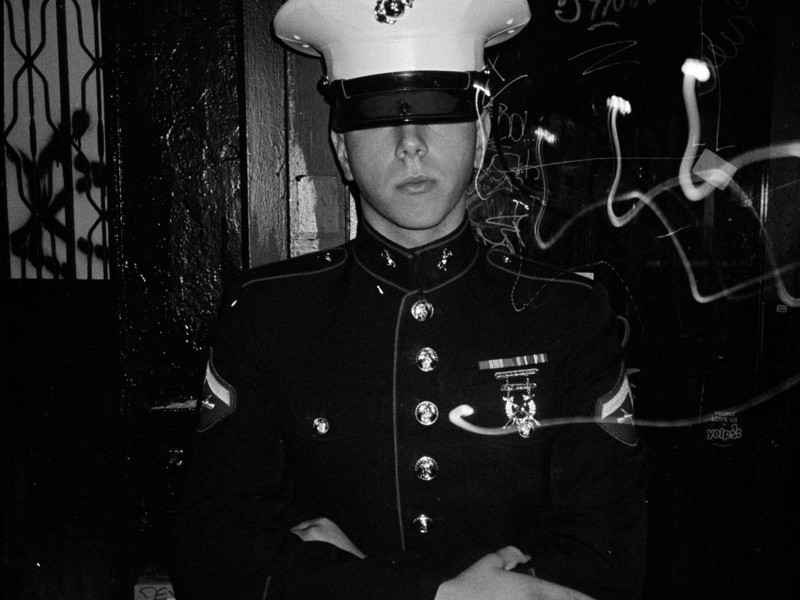

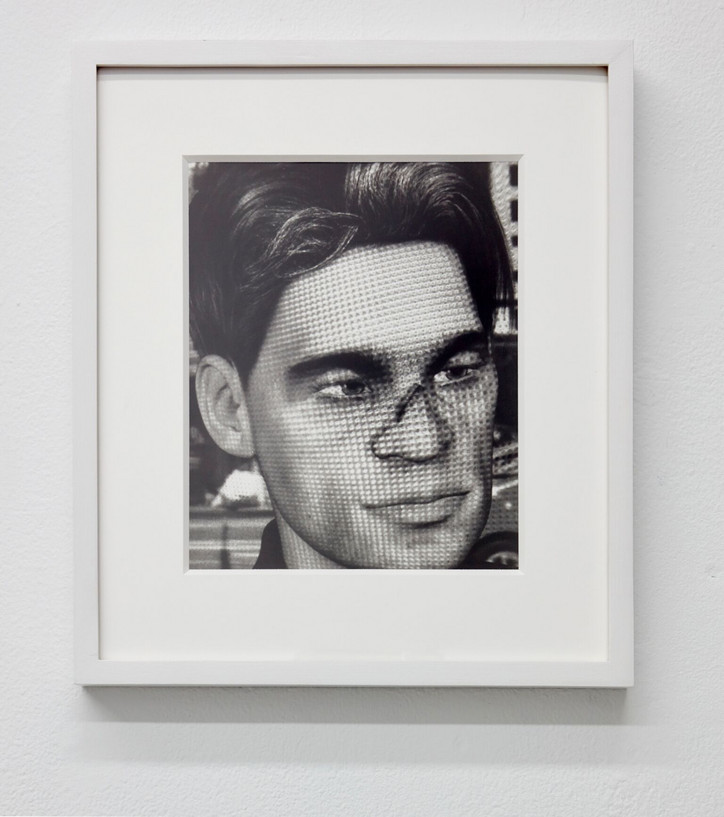

- Above left: Mike Tyson and Jimmy Jacobs, New Paltz, New York, February 1986, by Larry Fink (Promised gift of the Tony Podesta Collection, Washington DC) © Larry Fink; Above right: Blue Horizon, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, January 1990, by Larry Fink (Promised gift of the Tony Podesta Collection, Washington DC) © Larry Fink.

I’m trying to think of a good question related to the boxing photographs—they really are interesting to look at and think about you being there. What do you think they communicate that’s special?

Well, in a nutshell, I’m a sensualist and physicalist. And I’m an empathist. So, it was my gift and sometimes terror that I have a sensitivity or acuity that enters people very, very clearly and deeply and also enters the space and everything around them, and also whatever else I’ve seen from culture, from paintings to photography to music, all of those things flood into the instant, not necessarily intellectually, in the sense of our mind being clouded with thought and words, but just the way things are. Everything that you know comes into each moment, and in photography, of course, that benefits you.

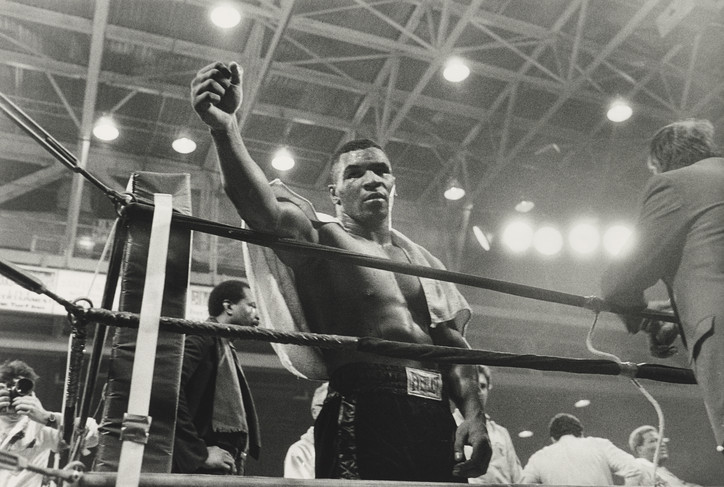

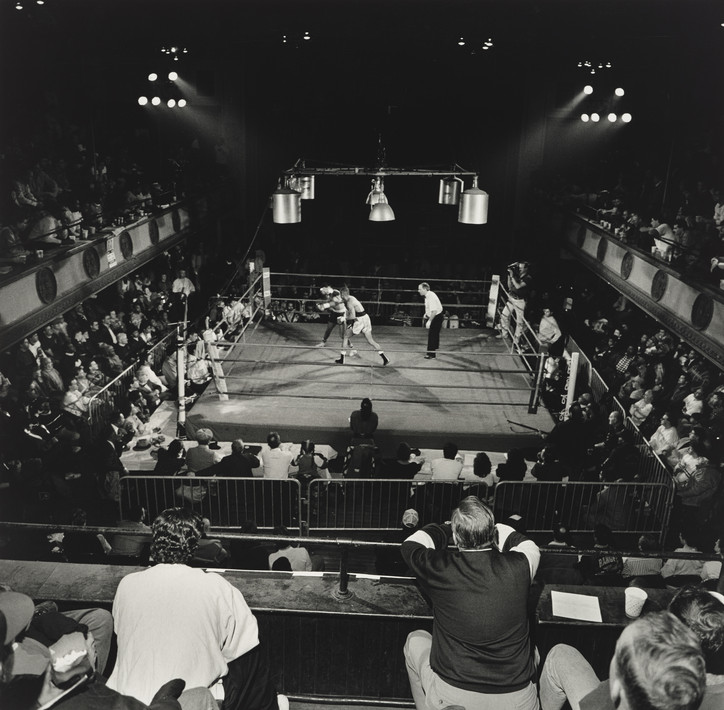

When I’m photographing boxing, it wasn’t so much the boxers in the ring that was interesting, but it was more the triumph, the innocence, the corruption and the greed, the physicality, obviously, the time where the ethnographic sensibilities of the people with their particular aspirations, that was what I was interested in, and it held me for about ten years like a magnet, this kind of theatre which it becomes after a while, and it is actually in its inception, because it’s about people who want to exhibit themselves in all kinds of ways, and power in all kinds of ways is very dominant. This was very interesting to me.

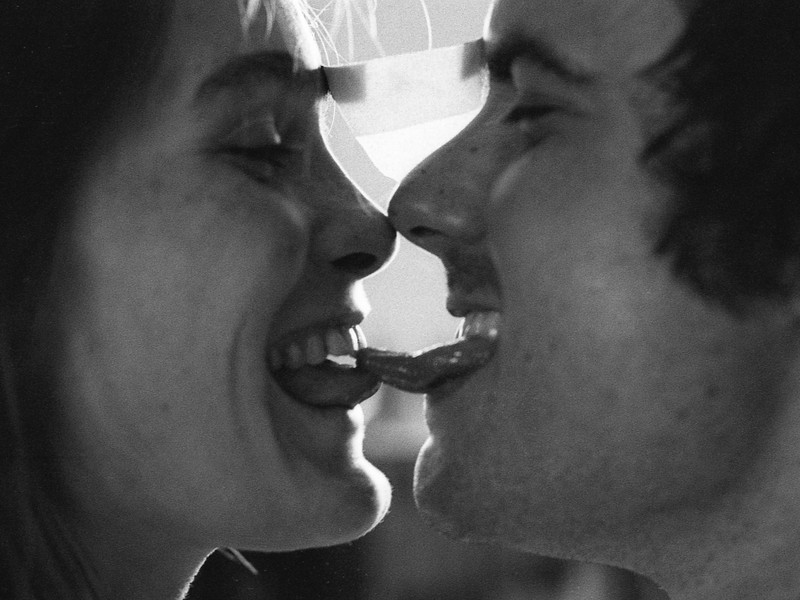

So you say you’re a physicalist and a sensualist. Can you expand on that?

No. I don’t need to. Sensuality is sensuality. Physicality is physicality. They marry. And I’m profoundly magnetized by those carnal—no, not carnal—human impulses. I’m trying to understand the nature of the tone of the energy that’s in front of me, call it a person.

I’m sorry, I missed something before that I want to return to—did you say you were working with aristocracy?

Yeah, I spent a month or two in Bologna photographing the Bolognese aristocracy. I’ve spent two months, but I’m going to go back three or four or five more times. It’s very interesting, the consequences of being an aristocrat, both absolutely poor, but still class, and absolutely rich and very much class, and the lines that are drawn, and the lines that are open, but one thing that has to be known: is that when you’re born to rule, you don’t know how to earn.

Do they still have a functioning aristocracy?

No. They have only the echo of it. One fellow I know holds up the class beautifully, saying the aristocracy has to be liquid otherwise it turns to dust, meaning that it needs to be flexible. Really, really interesting conversations. And they have, for the most part, the most glorious collections of art from the family, etc, all the way from the fourteenth century, these castles that they live in and what not, it’s really interesting.

Yeah, it’s interesting too right after we were talking about your interest in power with the boxing, do you feel like there’s a comparison there?

I’ve always been interested in power, the work you might know of called Social Graces, which is a fabled book of mine which came out in the 80s, which they say, to some degree, became the face of photography, and I quote—I wouldn’t say that about my own work—the academics take it that way. Also my use of light with the one-arm flash, which I was doing then, actually changed the style of lighting for many people, so I’ve done a lot of things with my skills and hard work. And also more than that, I have a really deep, entrenched curiosity about what it means to be alive.