Fake Puppies, Sloppy Kisses and Hilma af Klint

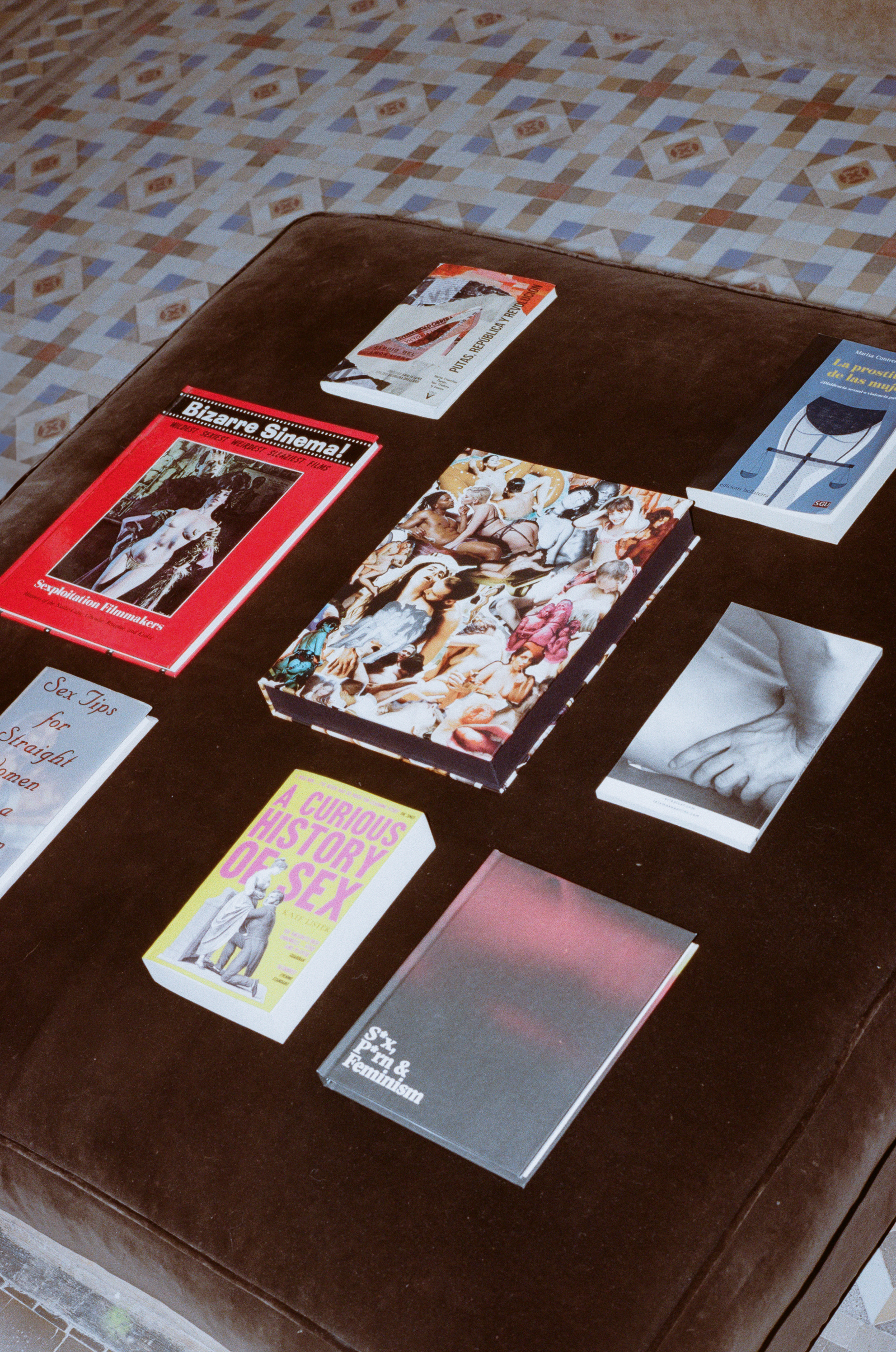

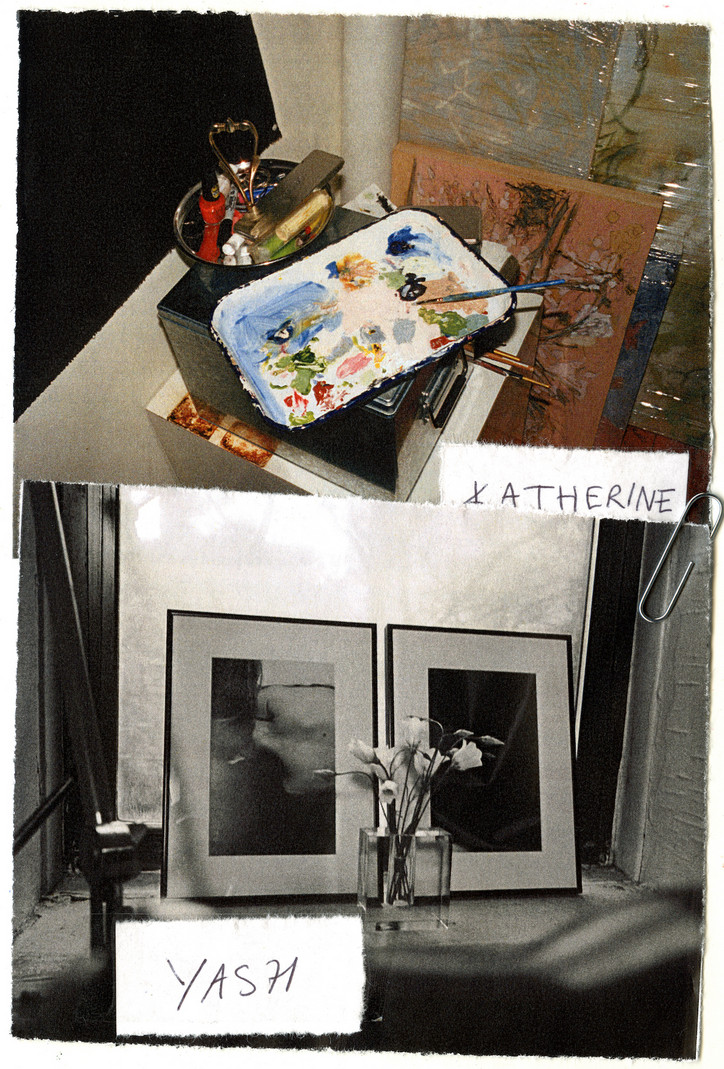

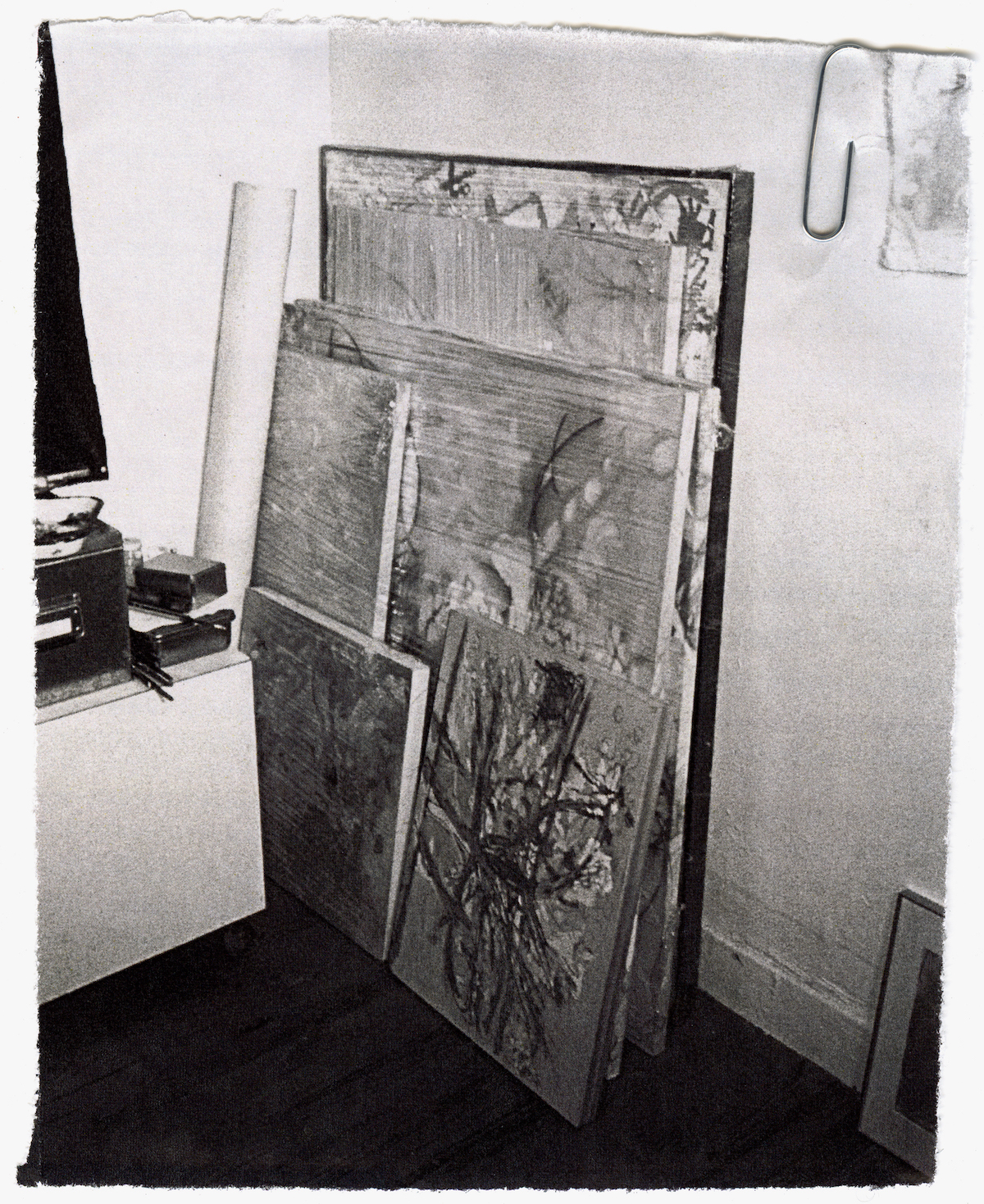

If female artists are discussed at all, they are discussed in terms of tragedy. Few are celebrated in their lifetime, and even fewer get a say in the legacy of their art. The Swedish painter and pioneer of abstraction Hilma af Klint, whose work is buried beneath the mess on their coffee table, is one example among many. But Auchterlonie and Yahshel refuse to be sidelined, selectively selling their work to buyers who they know will be able to properly preserve their work. Auchterlonie started the summer by exhibiting at the legendary Brooke Alexander Gallery on Wooster Street, whereas Yahshel began hers by turning down requests from European art fairs.

Below we speak of fake puppies, chain-smoking, love languages, sloppy kisses, desire, and of course, Hilma af Klint.

Katherine, you just moved in with Yahshel. I’m curious about what’s left behind in the old apartment.

Katherine Auchterlonie— I’m 95% here, missing the champagne glasses and some fake puppies.

Fake puppies?

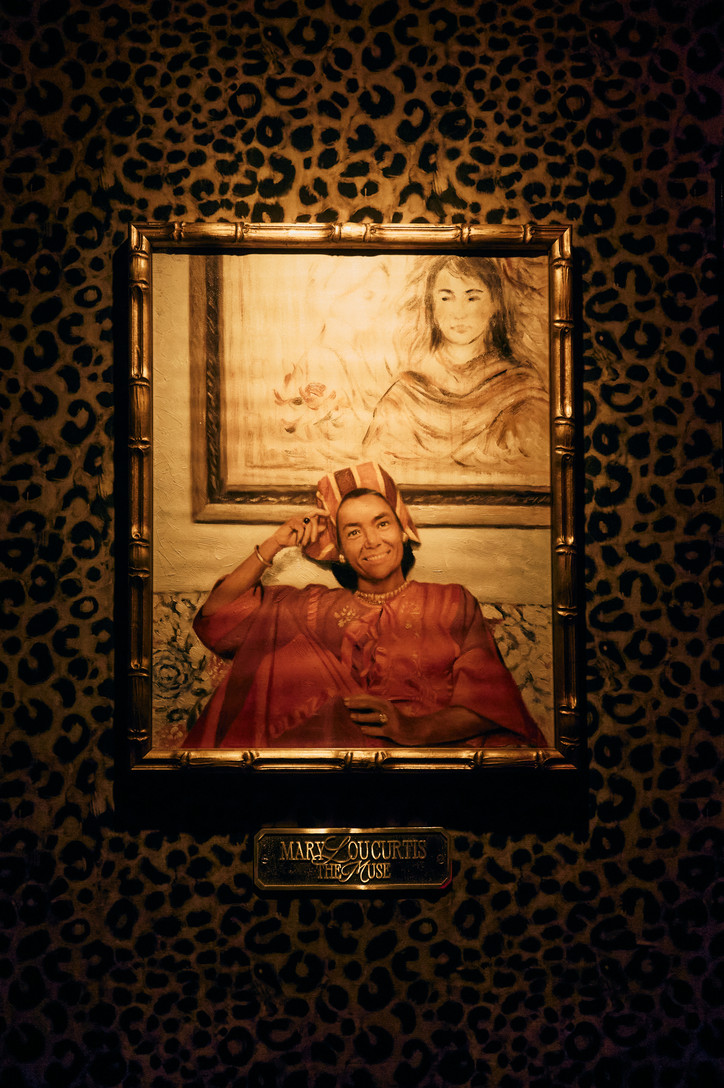

KA— They’re replicas of dogs in old paintings. “Old paintings” as in the 18th century when portraits peaked amongst the privileged and their painters developed a visual language to communicate “underneath the various forms of wealth.” The artists themselves seem cool but the subjects were often uncool people. Anyhow, a sleeping dog became a symbol of infidelity. For example, you’d see a portrait of a couple on their wedding day, both very clean, very dressed up, very happy, whatever; perhaps they would have the father painted in the background, and two dogs on a leash. If one of the dogs were asleep, it signaled that the groom was cheating.

That's brilliant.

I wanted to make something out of it but it hasn’t been my vibe lately. I’m not that bizarre right now.

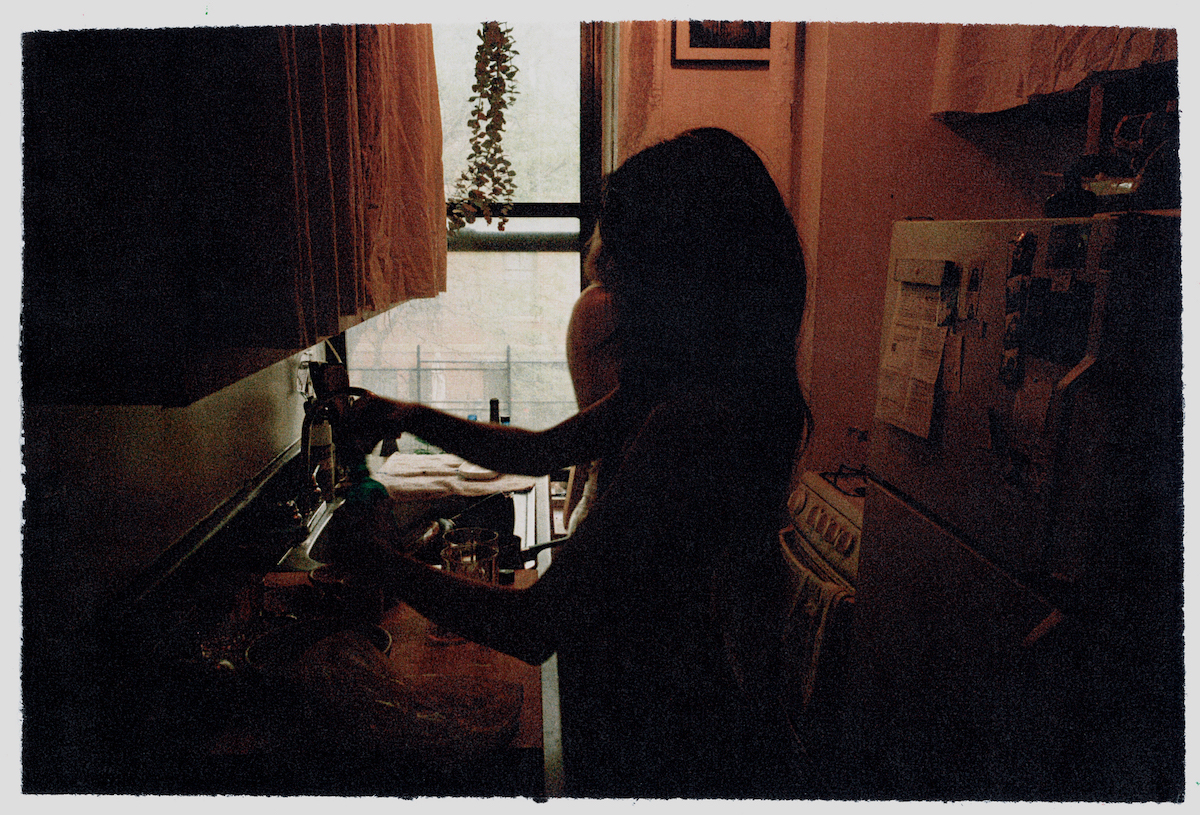

No sleeping dogs in this apartment. Who does the cooking, who does the cleaning?

Yahshel— I’m the chef. Kathrene leans heavier on the cleaning side if we’re being diplomatic.

KA— I wake up to the smell of her cooking.

It’s not even the sound, but the smell. She keeps quiet so as not to wake you up before the meal is done. That’s love.

KA— Cleaning is my love language.

Me sexting.

KA— But at the same time, I can’t have it too clean. I need an organized mess, especially a girly organized mess; some champagne bottle wires lying around, some old deli receipts, and… maybe a cracked eyeshadow? That’s when I’m inspired. That’s when I’m like “Okay, I know who I am today, let's get to work.” It’s an identity thing.

I was waiting for you to drop cigarette butts, too. Cooking and cleaning in all glory, but who does the cig-runs?

Y— We always pick up double packs at once.

How many cigarettes does it take to finish a painting?

KA— Oh my god. Let’s just say I’m glad my piece on Wooster [Street] is behind glass.

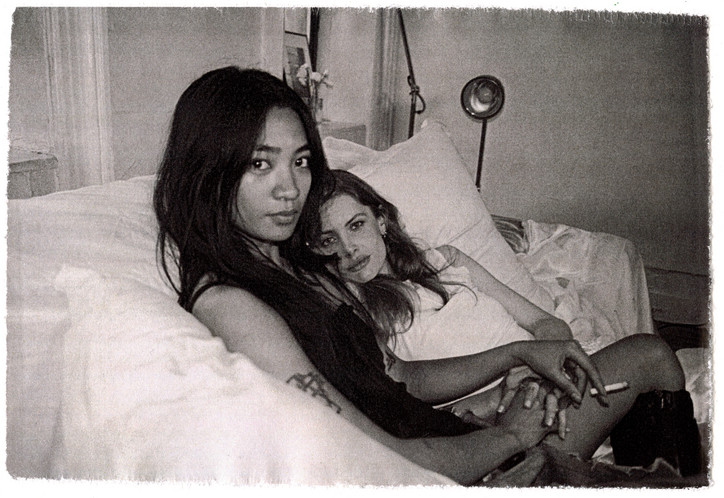

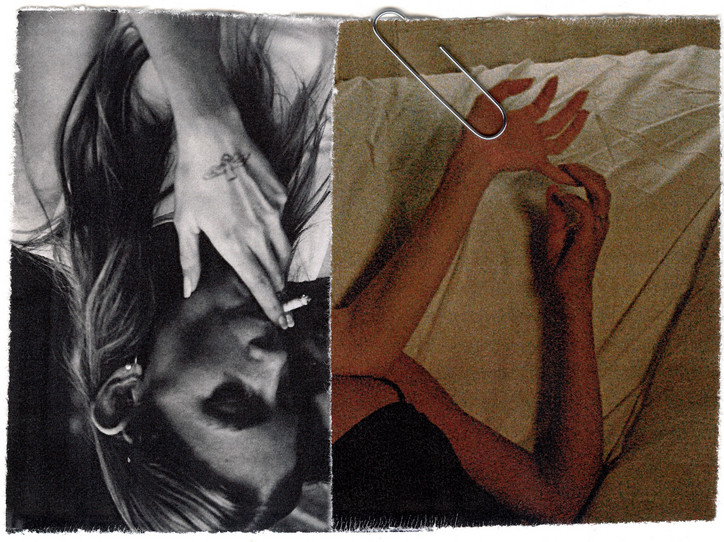

Through some of Yahshel’s photographs of you, it’s almost as if one could smell the smoke. I mean that in the most sensitive way. In your duo show at The Sitting Room [gallery], the works were displayed not only in conversation with each other but the symbiosis felt as if the works completed the other’s sentences. How much does your practice overlap?

Y— There isn’t a way that I could think of them as either dependent or separate.

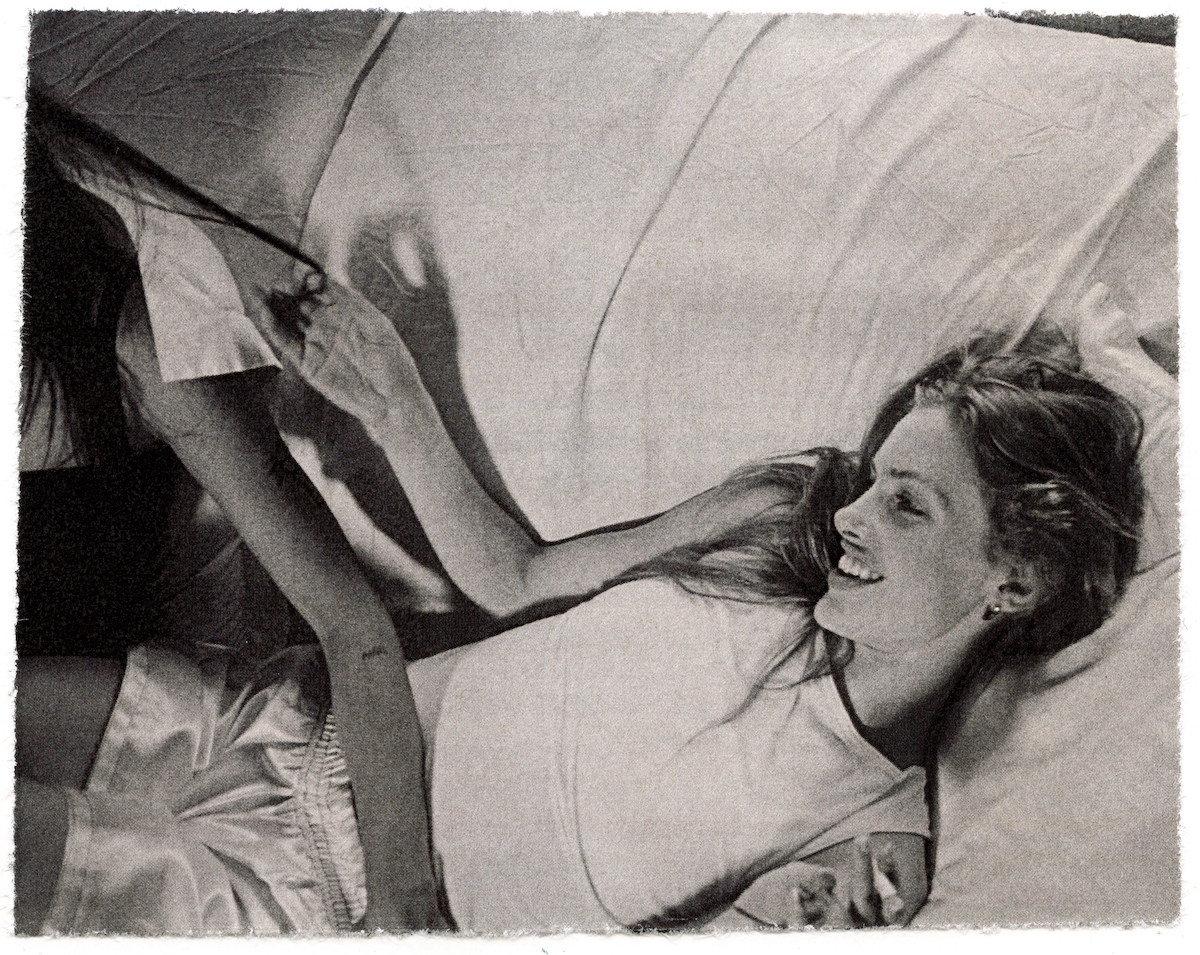

KA— I mean our art is our approach to life. And Yash is a big, if not the biggest, part of mine. She influences how I feel, and how I feel naturally bleeds into what I make. It’s inevitable, maybe in the best way possible, because it allows the work to go outside and beyond myself.

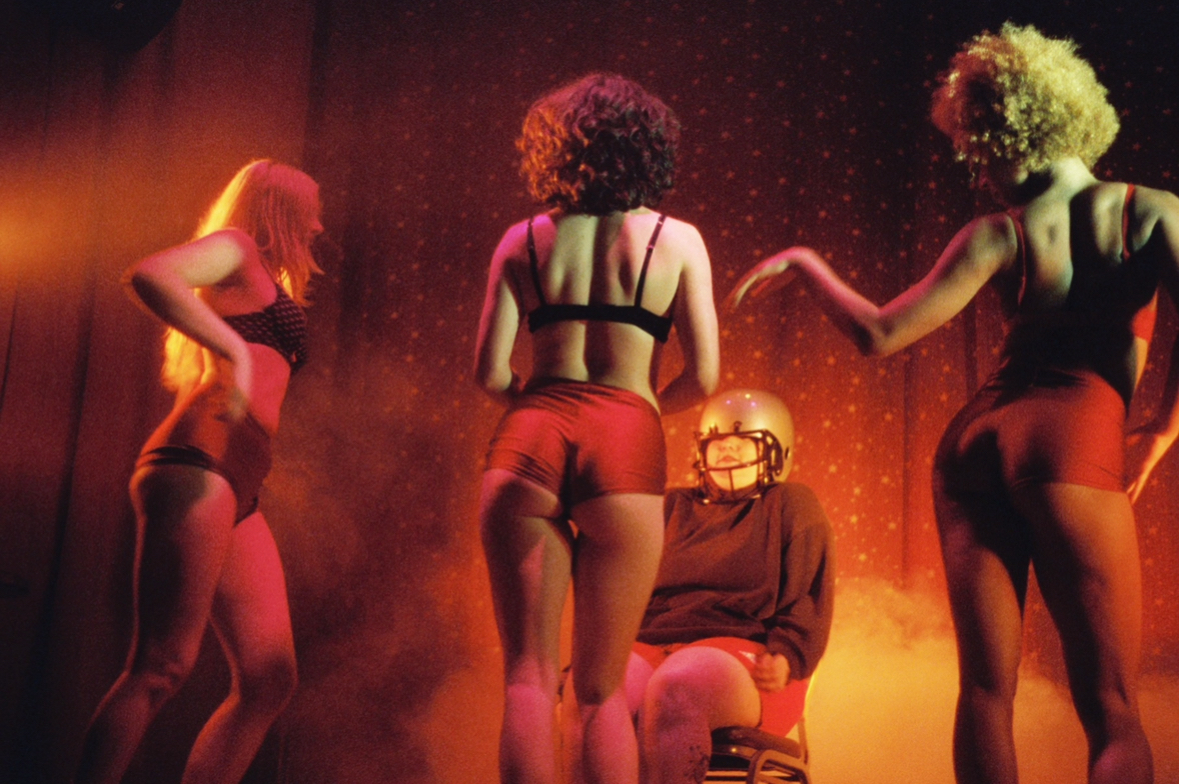

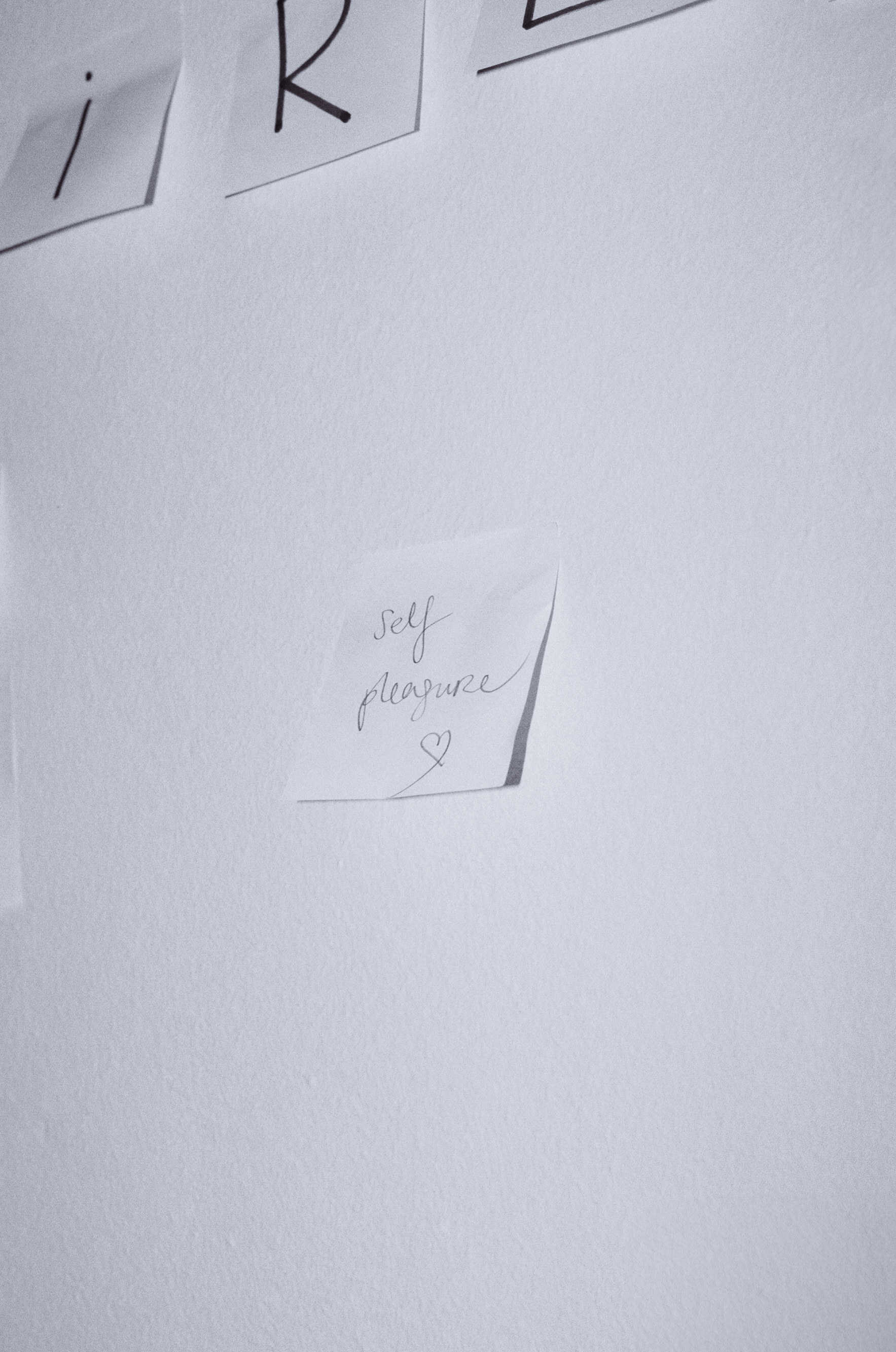

All my research for my upcoming show, dating back to last April, has been centered around a notation system for diagram kissing; kissing in a way that’s not creepy or gross. The motif, however, is completely without people. I’m fundamentally against pictorial representation — it just never interested me. I almost see figurative as Islamic and why would I as an artist care about representing what God already made redundant? My practice is more abstract; I would even propose this diagram exploration as a scientific notation, which scratches an itch for me. The ultimate goal is to create an open-ended code that anybody can read and, through it, visualize an entirety of that kissing experience of their own.

In Notation of a Good Make-Out Session — your piece for Unrequited — I visualize you and Yahshel dancing around while making out, and the X’s are either where her tongue touches yours or vice versa, or perhaps that's where the heart skips a beat? Or maybe that’s me being the creep you set out to cancel.

KA— No that’s hot.

The inspiration for that piece came from the “Feuillet-Beauchamp” notation — a dance sheet commissioned by Louis XIV. The dancers read these un-abstract abstracts and followed a choreographed dance based on the drawing. Once I stumbled upon it (via internet tourism) I was like, “Okay, this is it.” So now I’m charting love in a notation system; some movements are hot, elsewhere, the kiss could read as really sloppy.

Have the two of you ever had a sloppy kiss?

Y— Do you want us to show you?

Correct me if I’m wrong but this is where the artisanal overlap takes place, in the exploration of love?

Y— Sure. I guess we started exploring the subject artistically through some [love] poems we once sent one another, which later were used both as titles and the press release for the Sitting Room. Kate’s approach to the subject matter is somewhat biological…

I mean, there’s Hilma af Klint on the table.

KA— I’d love to be compared to her. No doubt biology was my favorite class, much more inspiring than (male!) art history.

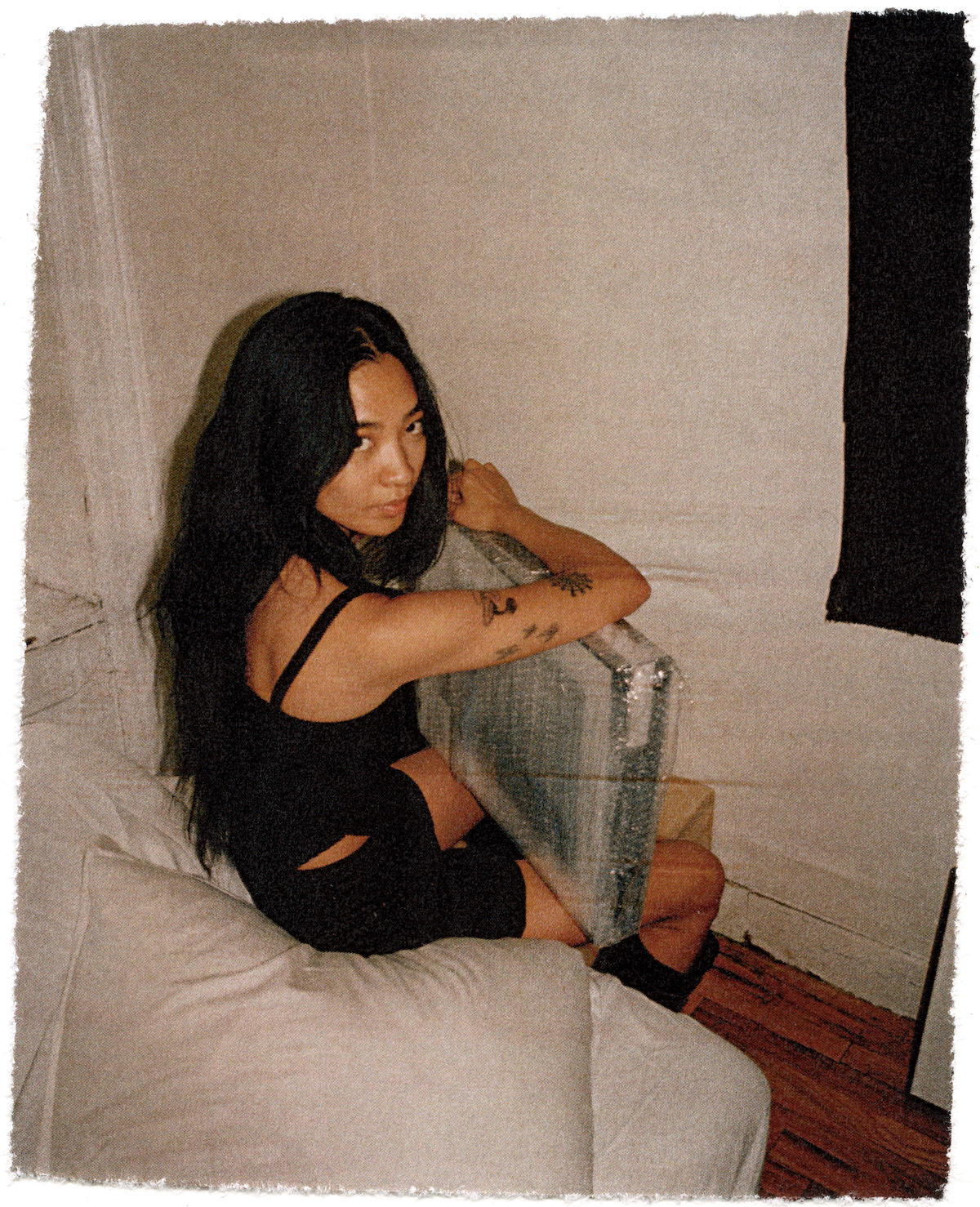

Y— Whereas my practice is exclusively photography, abstracted photography nowadays.

“Nowadays” dating back to when?

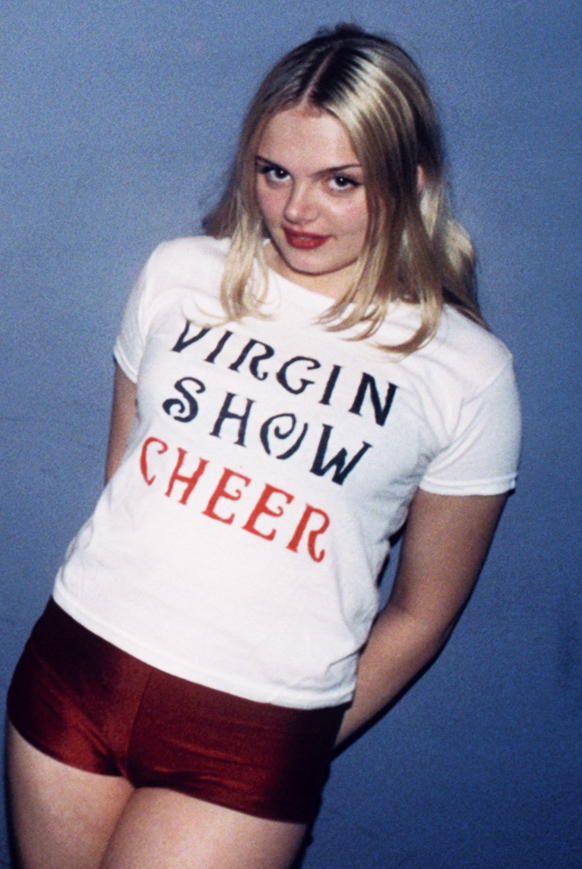

Y— I played with abstract for the last show mainly because of Katherine and how much I was exposed to her work. Before that, the majority of my photographs were straightforward portraits: friends having fun, fucking around, like any other “photographer” around here. Why I consciously didn’t tap into photography earlier wasn’t because I wasn’t curious, but being raised in the Philippines the idea of a profession has always been reserved for academics or sports. Art was never on the agenda. It took me moving to the States to realize that people are artists.

Until recently, I’ve always been “taking photos,” but Kate would roll her eyes and say, “No babe, you are a photographer.”

Your practice sits above the usual artist-muse relationship, thereby resisting falling into that objectifying false worship, and it’s brave, maybe even scary to expose something as intimate as one’s own love.

KA— The scariest part about being an artist, and a human being, regardless of what you’re portraying, is that you’re constantly hoping to be understood. Therefore, your work is somewhat contingent upon you being alive. Imagine growing up and realizing that the artists understood in their lifetime are men, whereas female artists are only later, after their passing, acknowledged as “underrated.” It scares the shit out of me. After consuming X and Y amounts of books, art history classes, and going through common art gallery conversations, was when I realized. The way people talk about women artists is tragic; they were never shown, let alone had a proper say about their art while they still were breathing. Or at the very least over 80 [years old].

Referencing af Klimt again, she’s such an accurate example.

KA— Exactly. She wasn’t an abstract artist, but google her name, go to any retrospective at any big institution, and all the labels, and websites, and auctions, will tell you exactly what she was repeatedly rebelling against. It proves that women were never appreciated for what they spoke of, but for what society was comfortable with. It doesn't help to make the work more direct. Nor do I want to. However, perhaps it inspires me to make my work physically bigger. It’s freeing to have a whole wall to paint on, almost like a cave painting. But it’s also a flex to be a small person and paint large formats. I guess that’s me saying that my dick must be bigger than yours.

What does it mean then to be self-taught?

KA— To have originality. It’s not about anything more or less than that. If you’re learning because secretly in your heart you want to look like something, or somebody else, then great, you’re a copyist and perhaps you should pursue that. You will make a shit ton of money. But then don’t come and claim this boho lifestyle. Your identity is not a painter. Saying it out loud now makes me realize how I believe it’s about intention, too. And intentions are harder to undress these days.

I’ve painted since the age of four. When the people around me started asking what I’d like to do once I get older, my response was always to be a painter. I’ve always had an answer, yet people kept asking me. Eventually, I realized that their asking was their way of saying no — if they had accepted my answer and my passion for painting, the question would have moved on a long time ago.

Y— It’s almost the same as when we run into people, and they keep asking if we’re still together. Why wouldn’t we be? We’ve also been told that it’s severely stupid of us to date each other because we could do so much better financially. It’s hidden in their phrasing, the tone of their voice, “But you’re such a pretty girl, you could be with someone who could provide you with…”

I believe that if you’ve truly ever experienced love, you would never question another person’s way of loving.

Y— Regarding your question on the scarcity of intimacy, I see the responses toward our art and relationship as validation for our work. Not because everybody votes for it but because they’re suspicious about it. It adds a dimension of social responsibility. It addresses that today, people are terrified of being vulnerable, even amongst their friends, and sometimes even around their loved ones. It’s as if we’re all set out to use the same script once we move through these interactions, and if we don’t we’re doomed. Love will always look different, but the kind of language that I hear is so damn uniform.

KA— You’ve got to have a communist mentality. My feminist theory professor would always say, that regardless if you have to make your change go beyond the span of a lifetime, eventually, your voice will be heard.

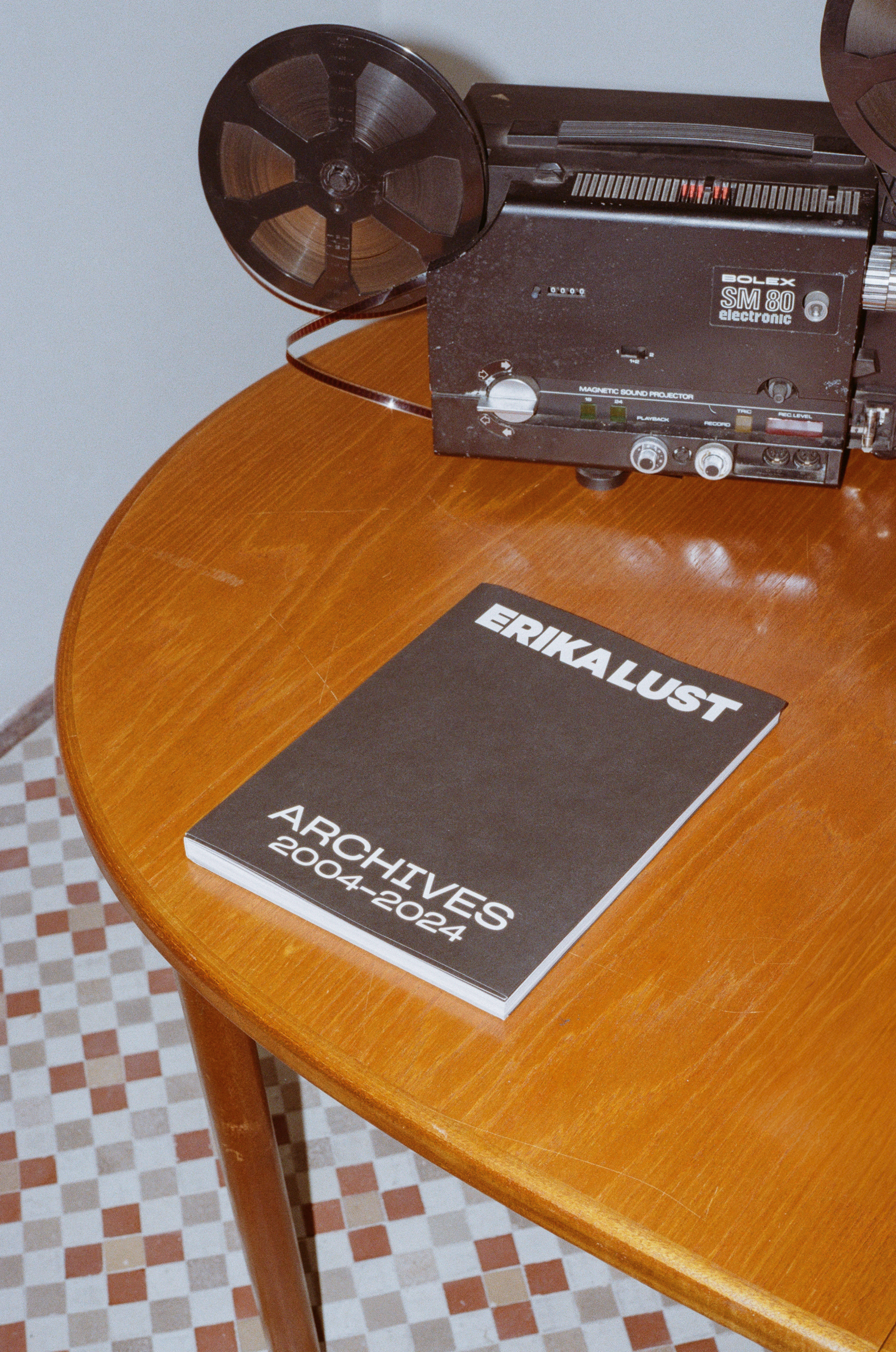

Y— That’s why archival works are so fucking important.

Making art is different from the drive to preserve your work, how do you create from that desire?

KA— It’s all the same to me. You have the drive to preserve your work because you truly believe that it is that important — because it needs to stay after you’re gone and, you know, you can’t take it with you when you die. Once you realize its value, you start aiming for galleries and private collections, then museums, because at the end of the day, you need people with air conditioning to buy your work, because that's how it stays in good shape.

Suddenly you’re no longer making art for your mother’s walls; she’s out of space, the house out of empty rooms, and eventually she will be gone. Eventually so will I. And I can’t archive my own work because death is real.

Only for humans. Original art is immortal.

Katherine Auchtomom’s Kiss Garden will be on view at Ross + Kramer Gallery until August 16th, 2024.