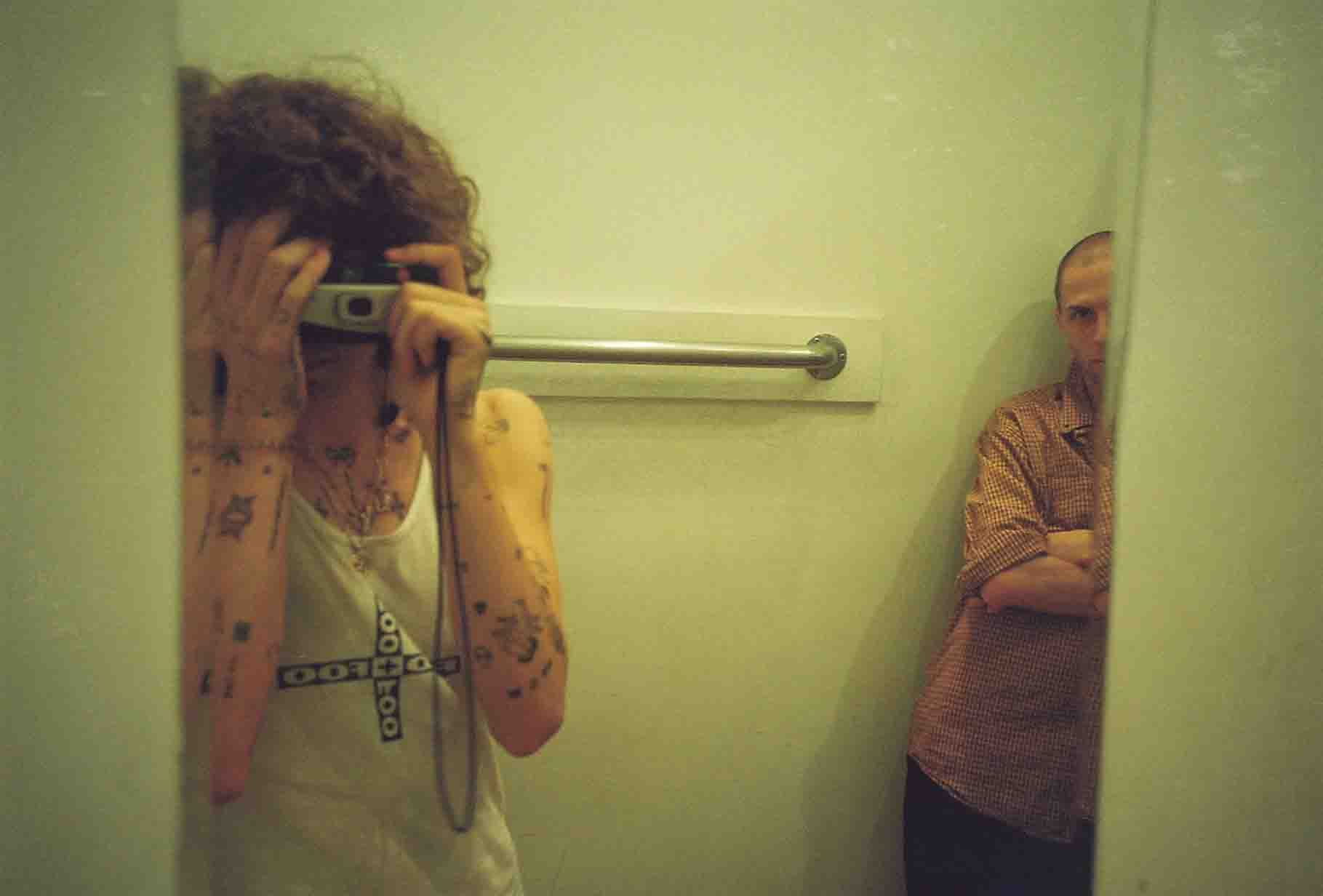

What pushed you to pursue photography as opposed to other fields?

We’ve been interested in photography since a young age, we took a photography course in high school and never looked back— we got our start in fashion photography, which we still work in. Although both the art world and fashion have their differences, they share many parallels with each other, particularly for photography. It always felt natural to us and this medium has allowed us to participate in both worlds fluidly.

How has your Cuban-American heritage influenced your work?

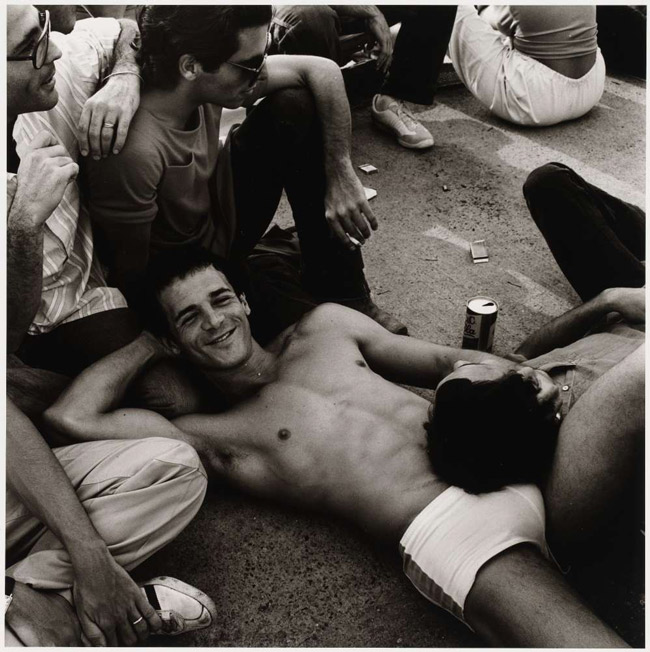

It’s had a significant influence, particularly for our art practice. There is this mystery behind Cuban culture and religion, given its complicated history, that people who aren’t Caribbean may not necessarily be aware of. It’s culturally diverse and there’s a duality that’s steeped deep in the narrative of the island that sort of became our point of reference. Being twins, Cuban-American and raised in a biracial family— there’s a binary there, which has always been present in our everyday lives. Our work reflects all of that.

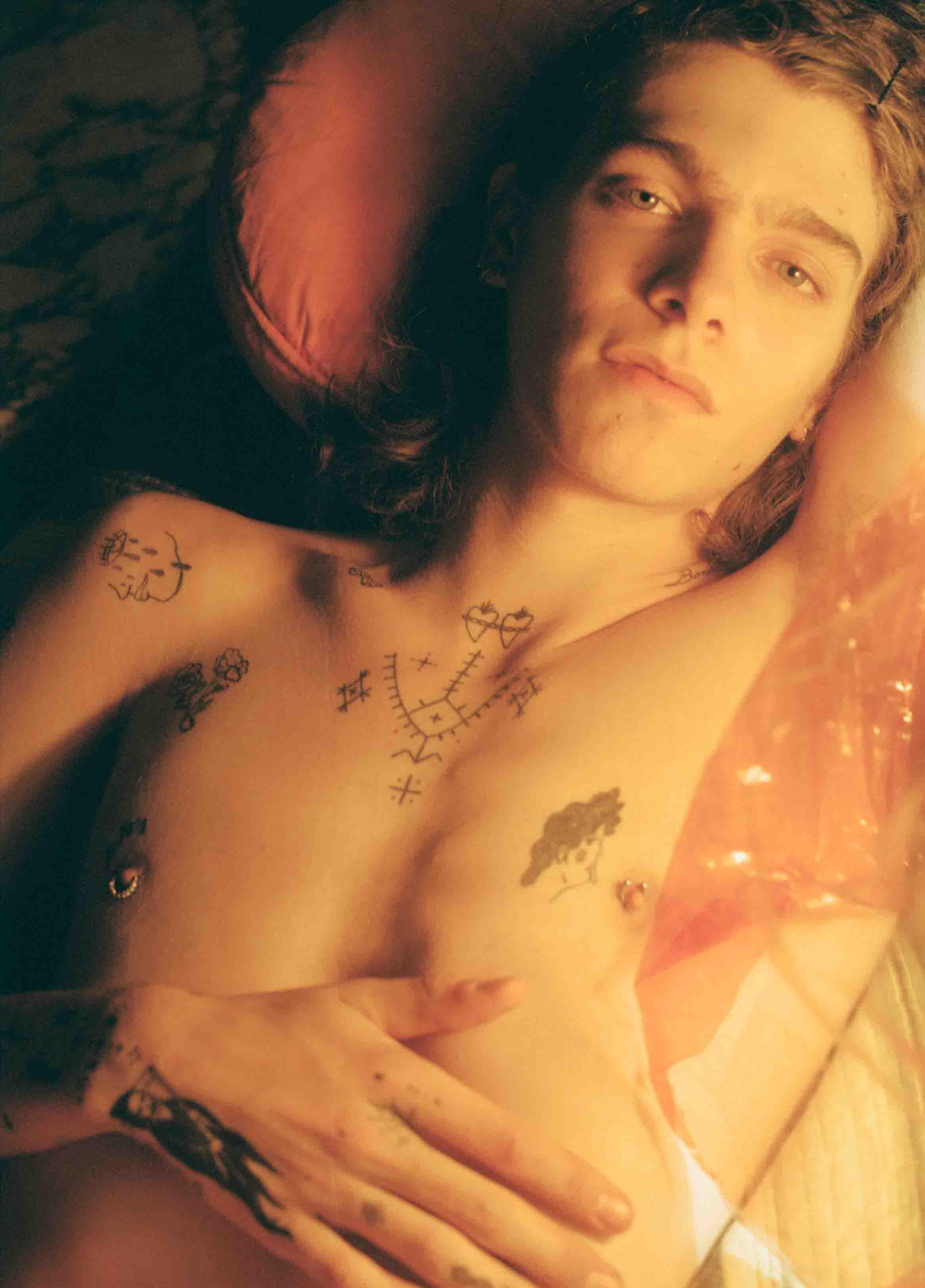

You cite a theological upbringing that explores the element of mysticism of gods in mythology, Yoruba and Catholic syncretic elements. How have you weaved such influences in your photographic practice?

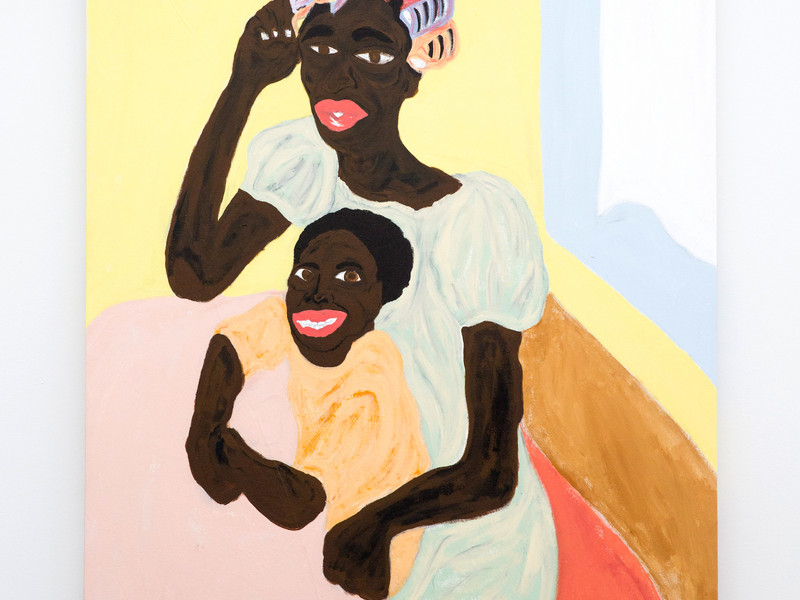

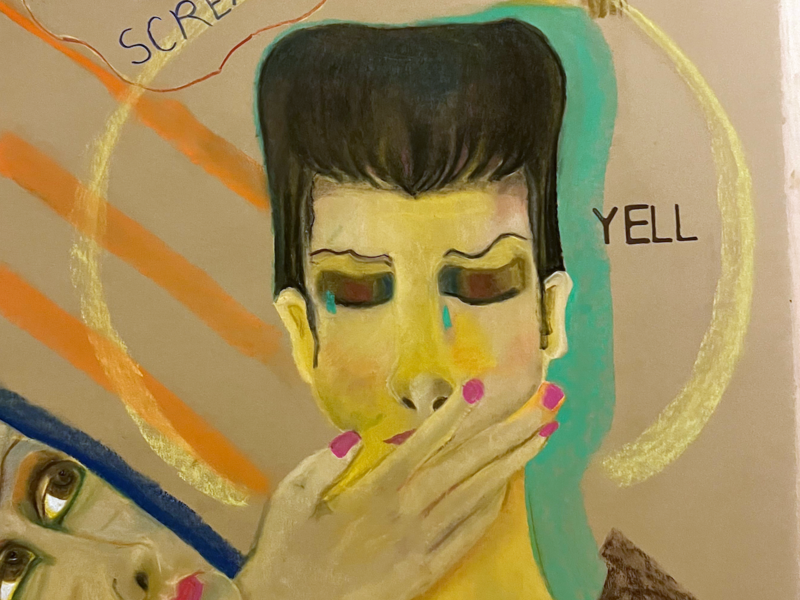

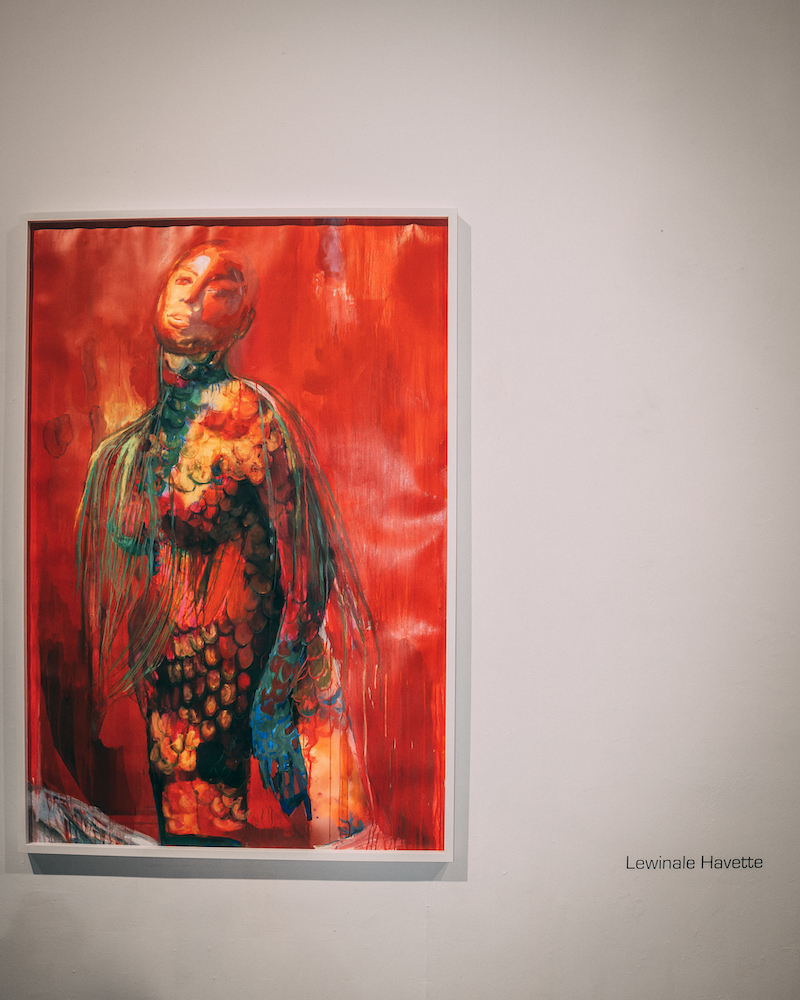

Cuba’s religious influences are unique to the island— it once belonged to Spain who colonized it, decimated its native people and took enslaved Africans for labor. Between the influx of the Yoruba people from West Africa and the Spaniards, a syncretic belief system was born. One that essentially merged two unlikely theologies into one, referred to as Lucumí. It’s a spirituality embedded in the DNA of Cuba and passed down orally over centuries. Working from our own cultural background, these deities and folklore stories became the center of our work, visualizing our own interpretations of them.

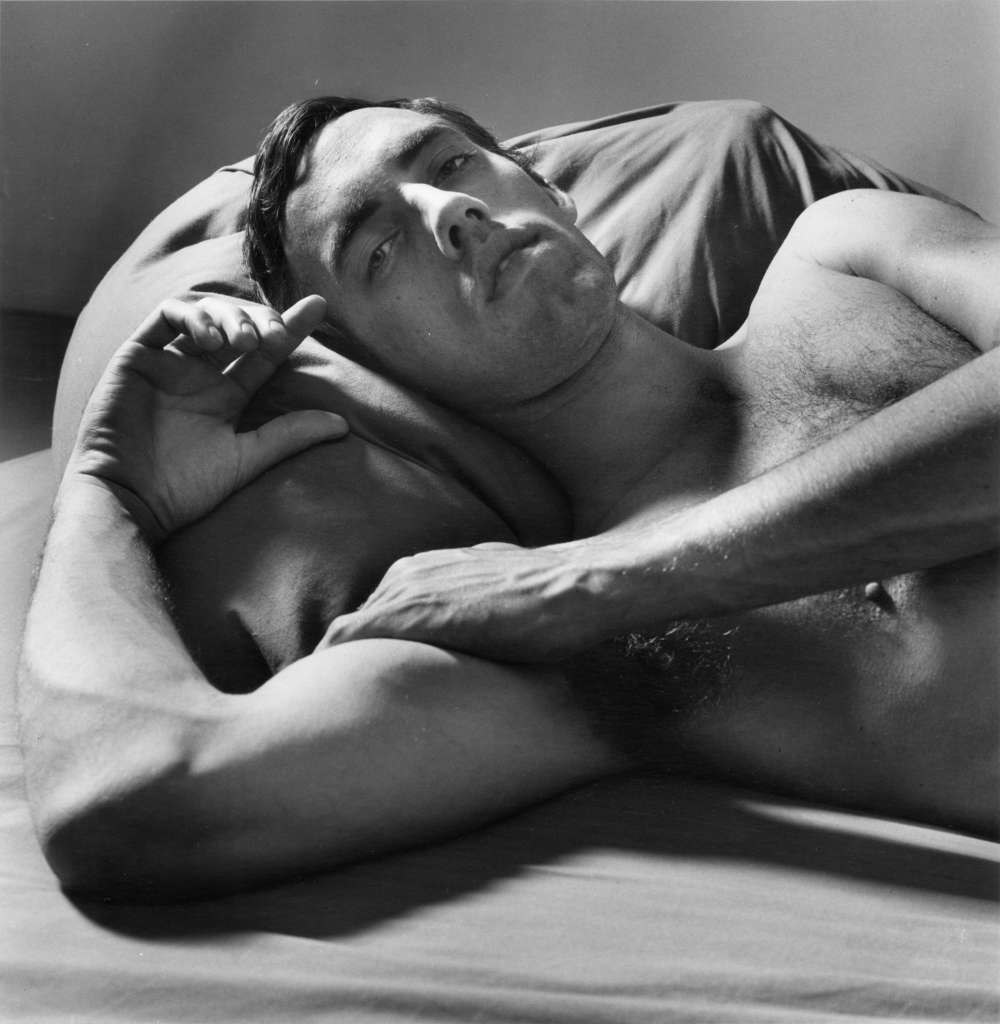

There’s a lot of historical references that permeate your work: how do you contextualize them in your broader practice?

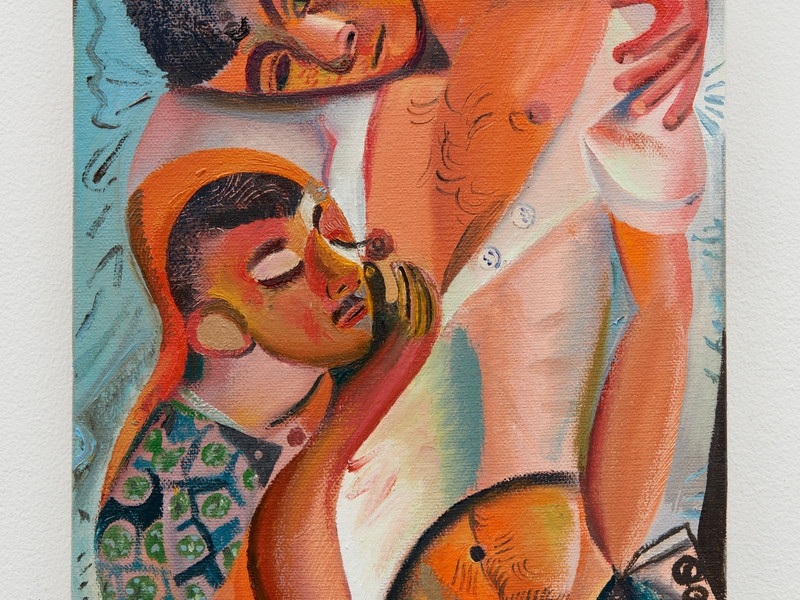

Being first generation Americans, we were exposed to many things our family was not. One of them is the discovery of art through traveling. We’ve always been interested in art history and the way in which it relates to us. We recontextualize and even reappropriate art historical paintings that have been canonical for centuries, but historically have excluded other narratives. We’ve taken the symbolism within these works that may have meant something different to the artists who created them during their time period and translated what they could mean in our culture today. For example, take the Grande Odalisque (1814) by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, which lives in the Louvre. A representation of a venus, holding peacock feathers in one hand. Oshun, who is syncretized with the patron saint of Cuba, became our odalisque; covered in crystals and surrounded by hues of yellows, a color that has always represented this deity. The peacock feathers are also a symbol indicative of Oshun. Seen as a venus of sorts herself, it only became natural that she represented this iconic painting for us.

How did you edit the curation of works for the exhibit at PHOTOFAIRS?

This was actually done by our gallerist, Anthony Spinello, who always does a great job at curating the work in conversation with each other. This exhibition will showcase works from our first exhibition with Spinello Projects as well as new works created for Photofairs NY.

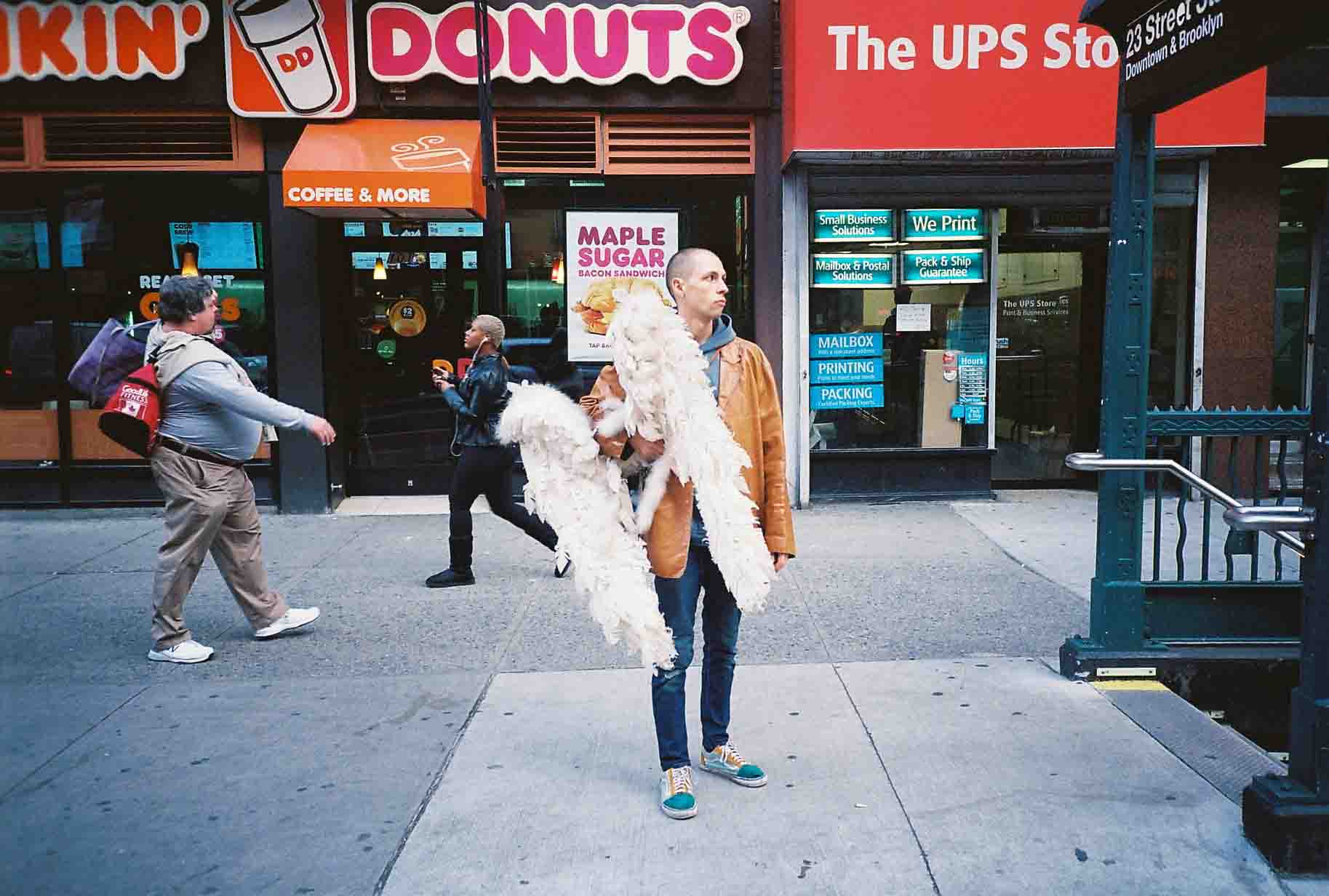

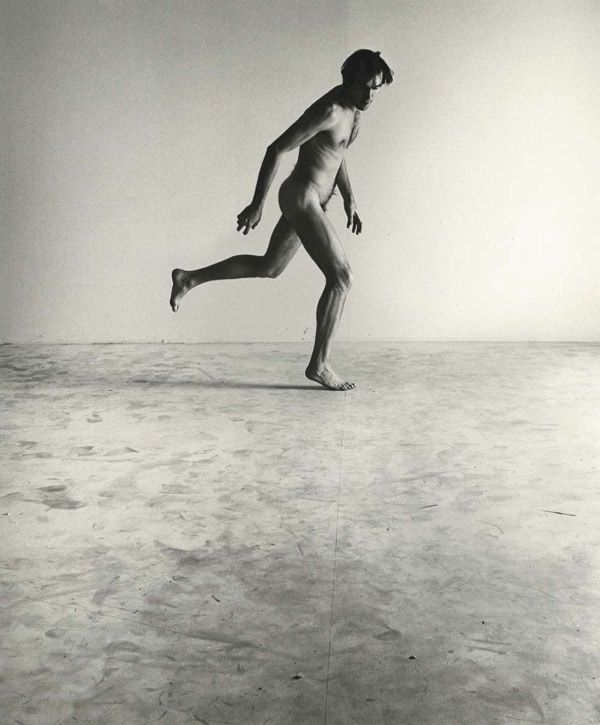

What is the key message you’ve discovered - can be past or contemporary - when capturing your subjects?

That everyone brings something new to each portrait. Doesn’t matter how much planning we can do, there’s always a collaborative effort that takes place which can spontaneously change things in an exciting way we may not have expected. The end result always being exactly what it was meant to be, even if it isn’t exactly how we pictured it.

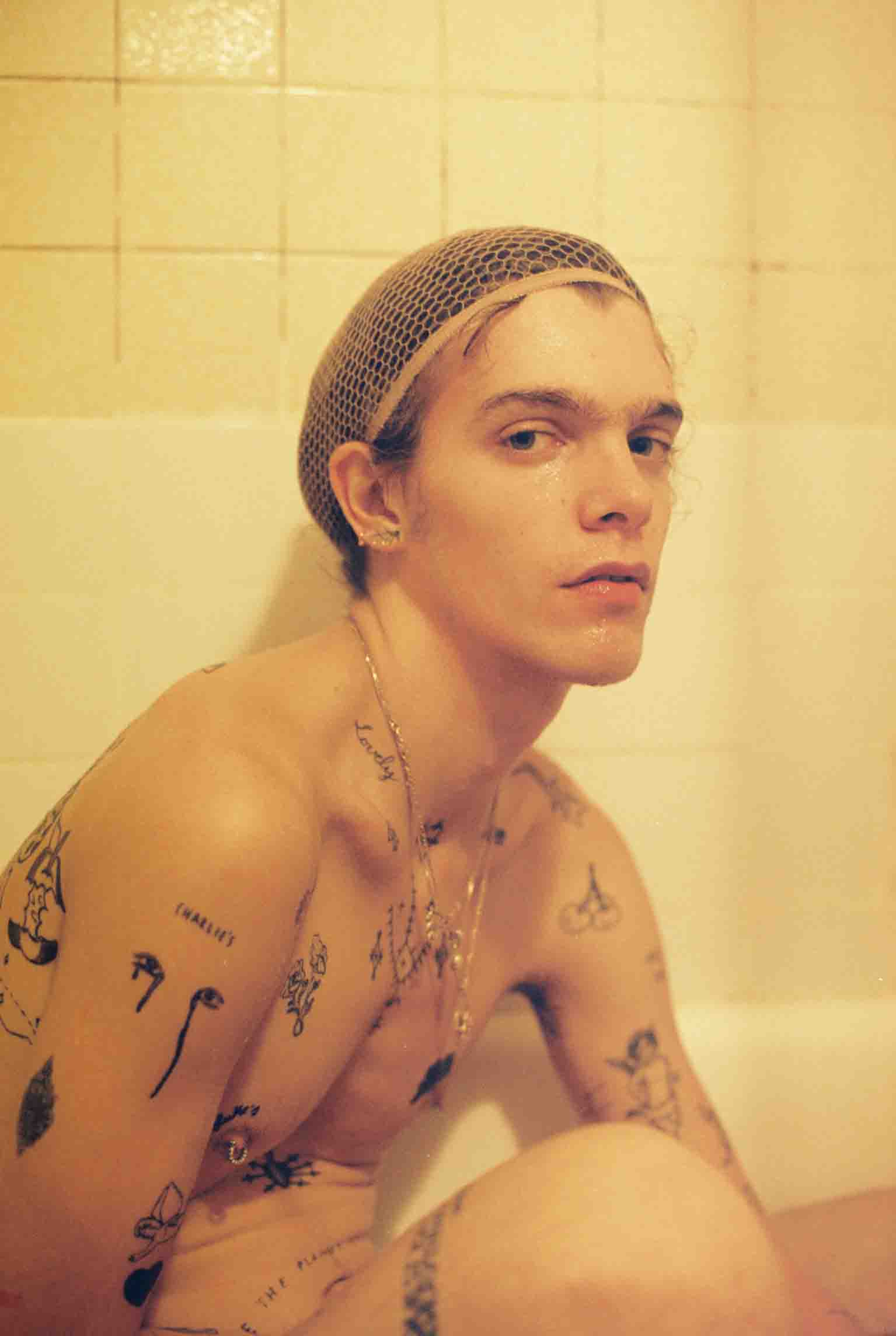

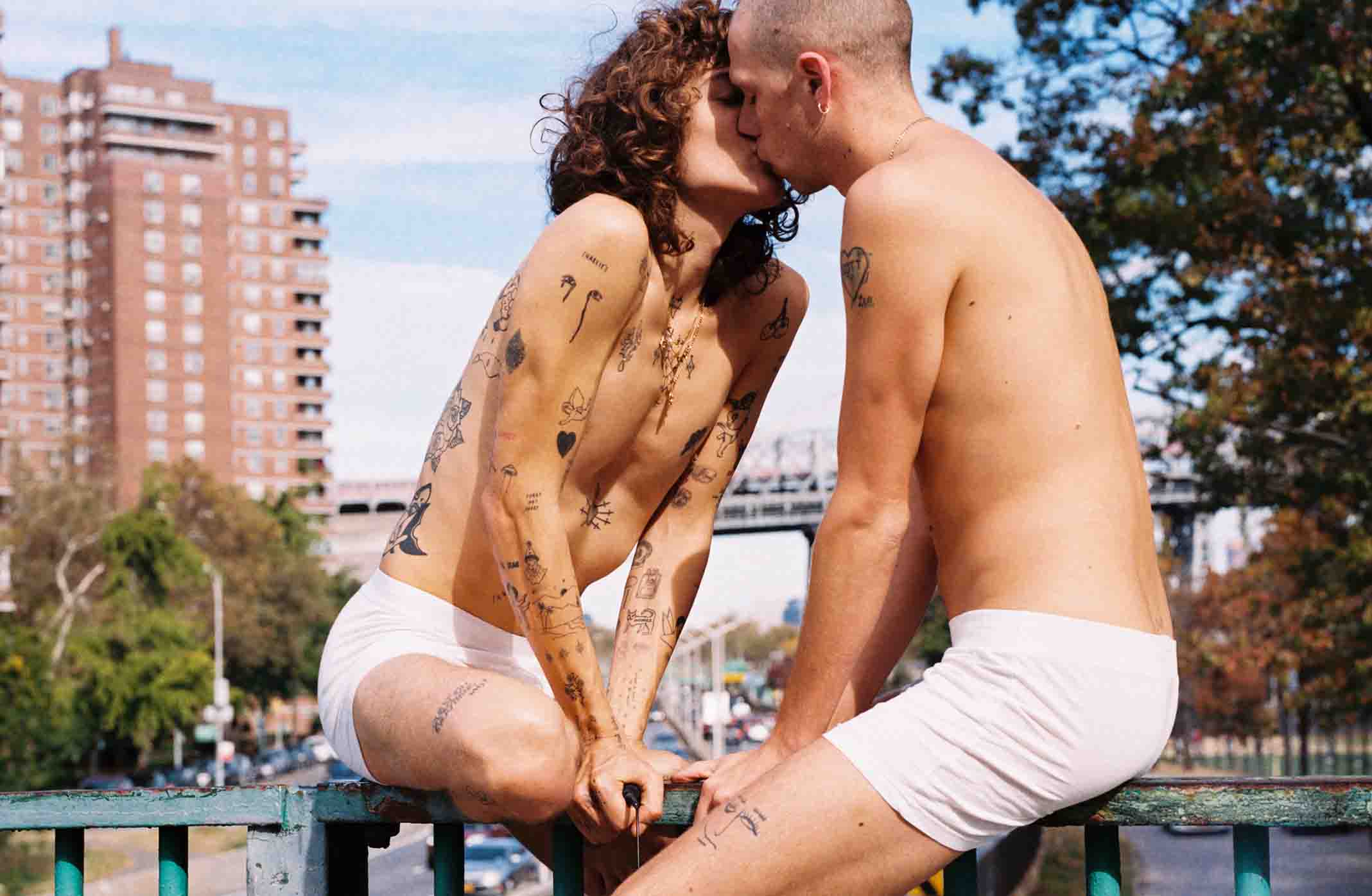

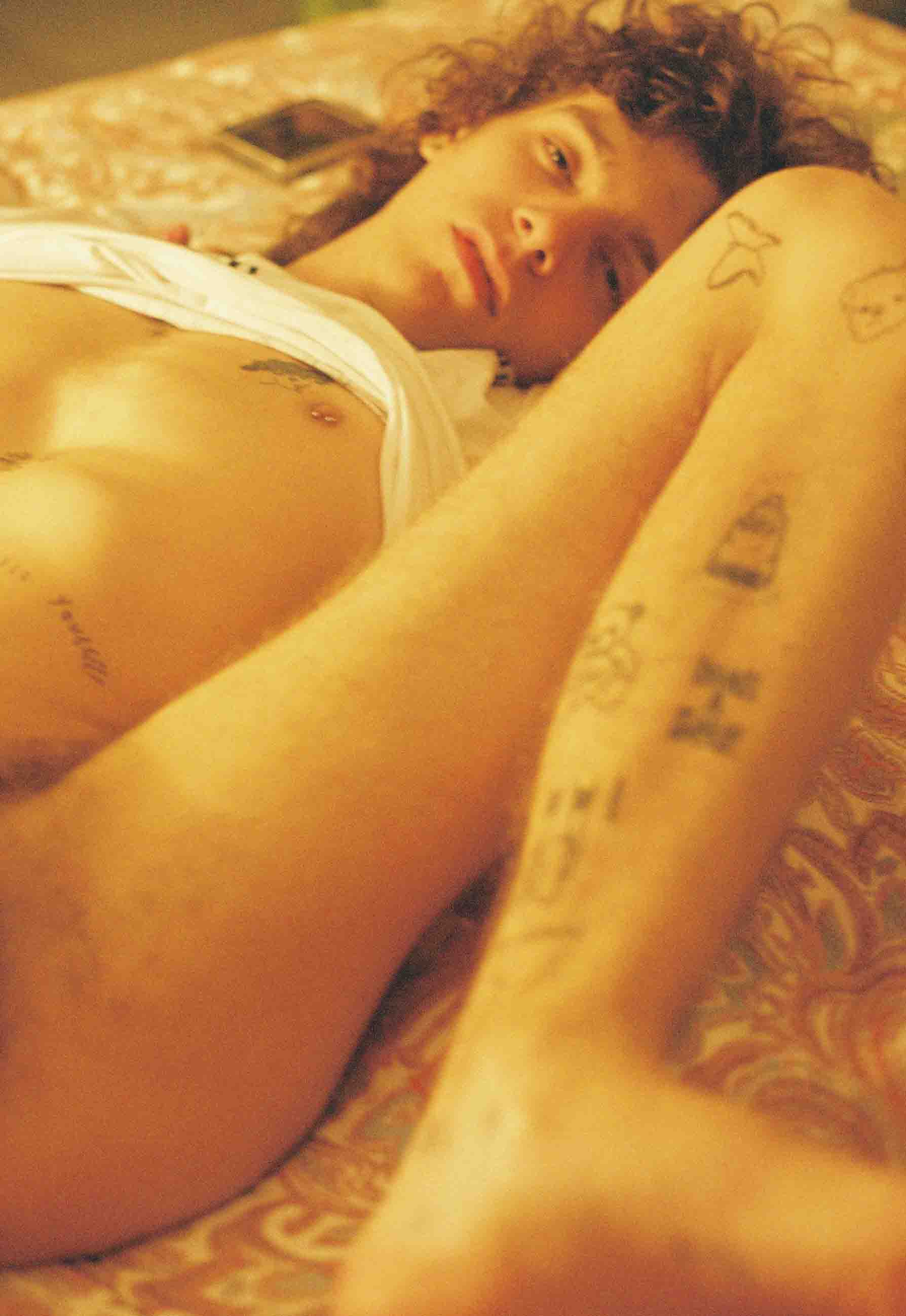

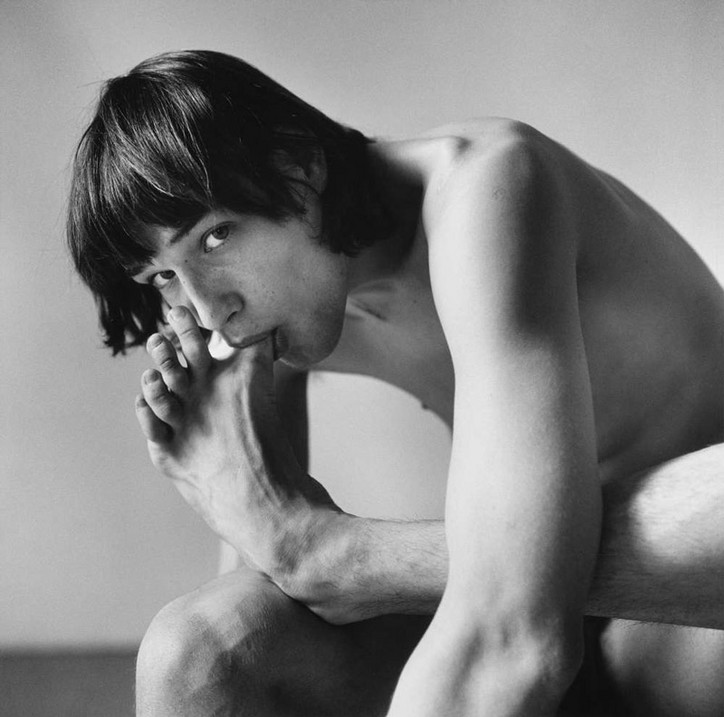

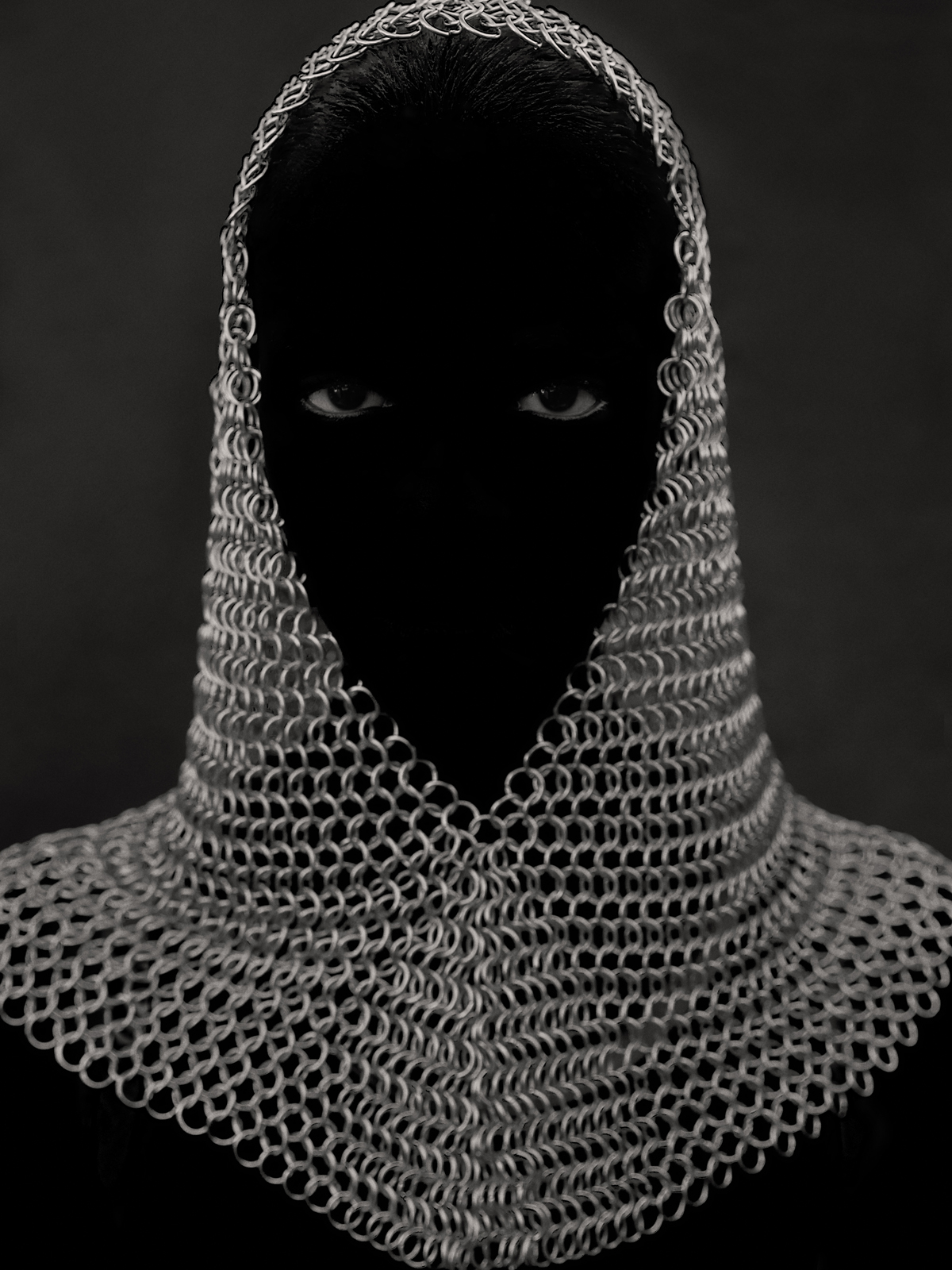

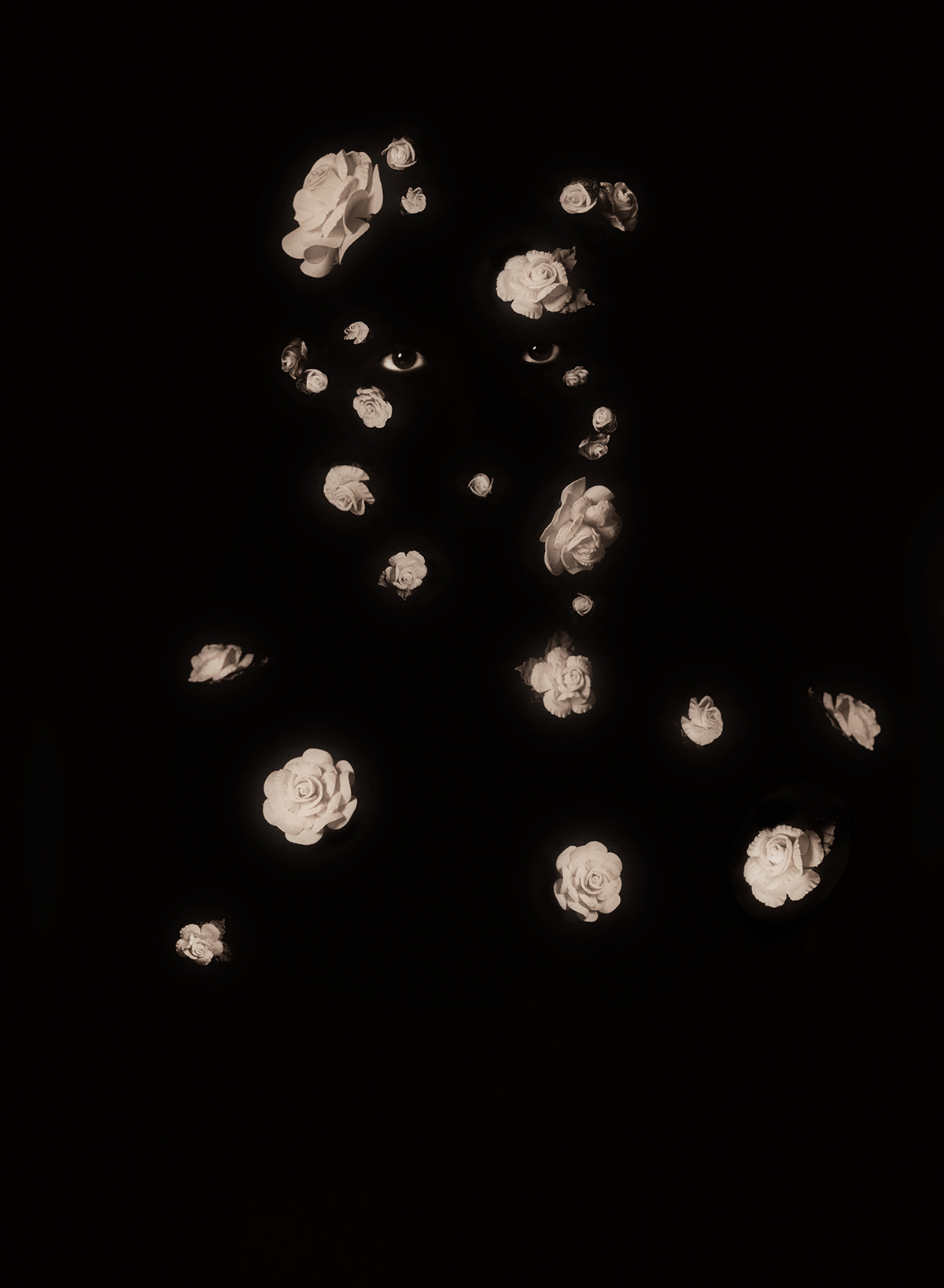

There’s a sense of anonymity that comes through the gaze of your subjects - who are they, Exactly?

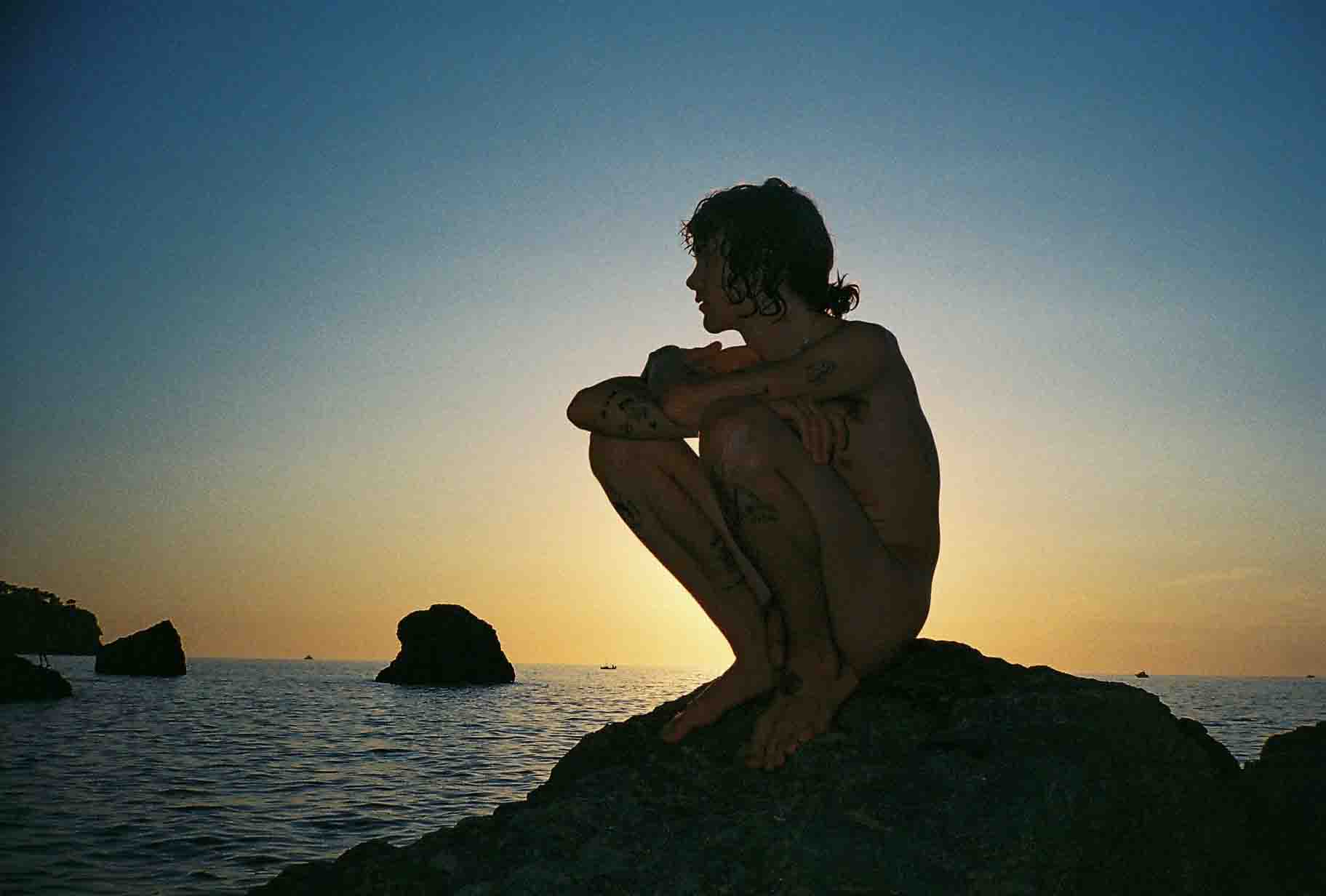

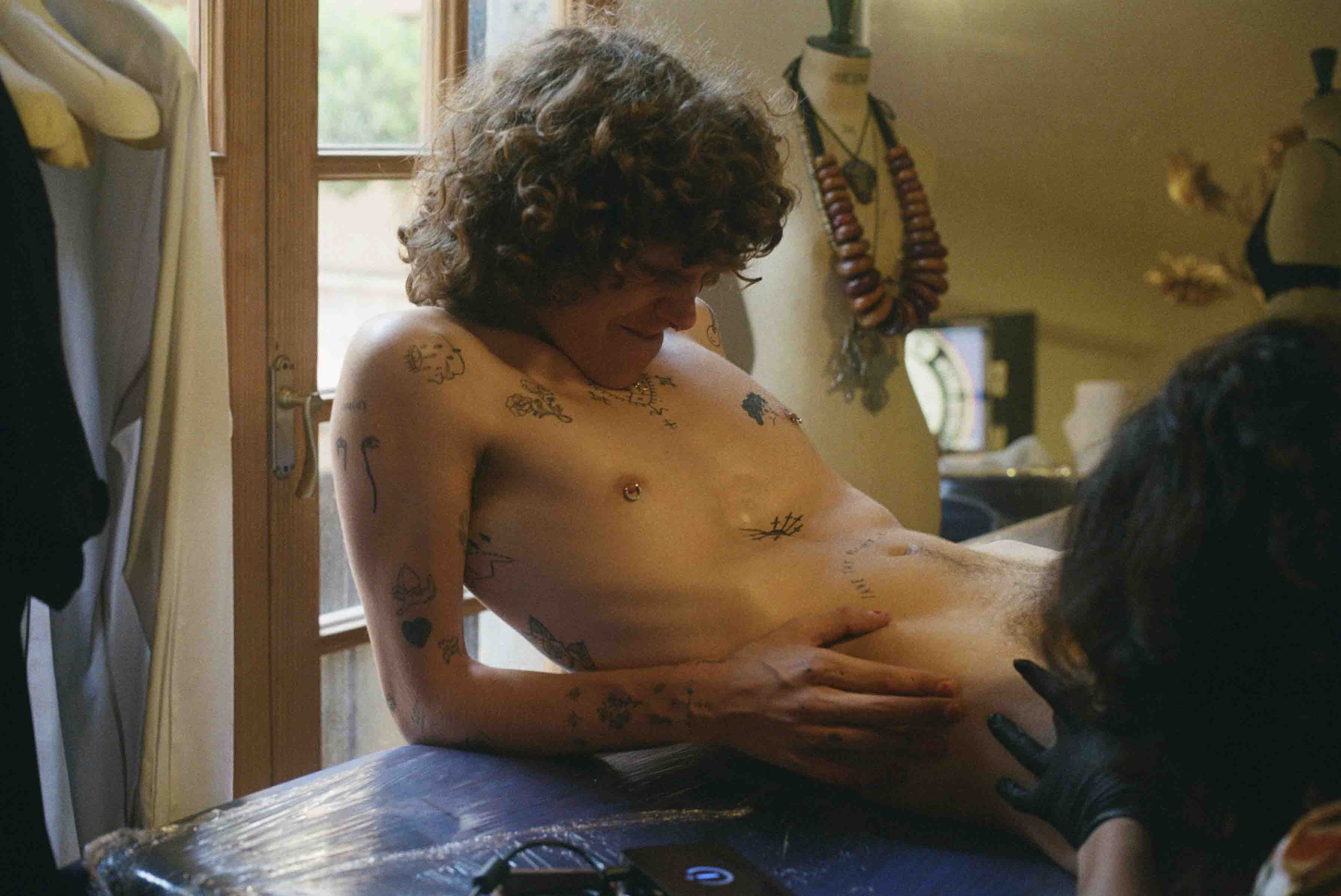

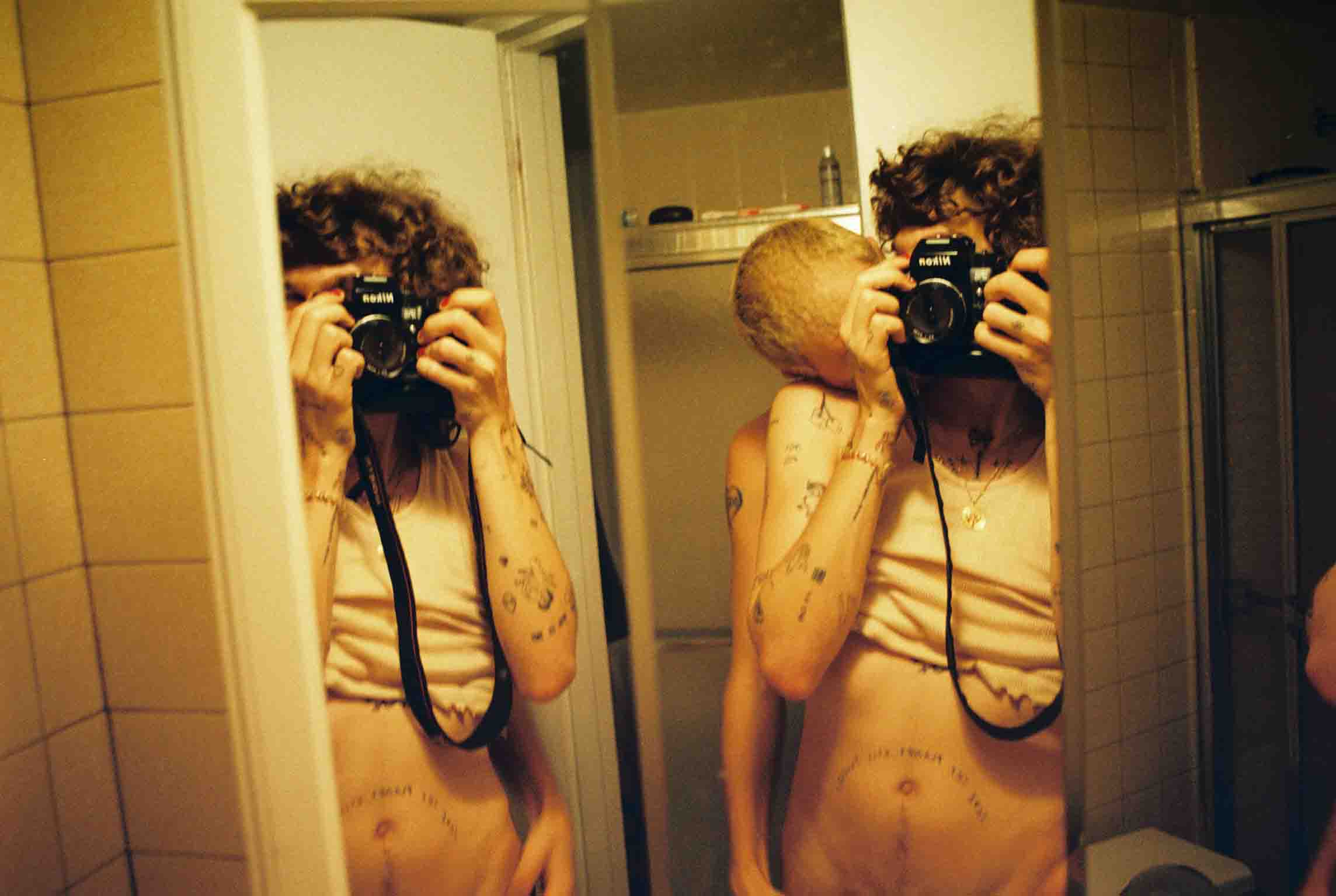

This part of our images presents both a thrilling challenge and an invigorating opportunity. We aim to create photographs that possess an enigmatic essence while still being relatable to any of us. Within their concealed identities, there exists a universal sense of empowerment. The ability to grasp the essence of an image isn't contingent on identifying the subject. Coming from a background in fashion photography, where significance often hinges on the subject's prominence and recognizability, this opportunity offered an interesting avenue for us, from what we were used to doing. Though the work is still photography and featuring actual individuals (friends, models, and family members), portraying anonymity in a creative manner presents its challenges within this medium. The shadow figures we depict maintain a powerful presence, irrespective of their identities—whether shrouded in blue body paint, obscured countenances, or clad in full-body suits with only their eyes exposed. This artistic choice reflects the historical existence of Lucumí living in the shadows and its contemporary tendency to remain concealed for certain individuals, partly due to the stigma within religious circles.

As symbolism is quite a potent undercurrent within your work, what’s the most challenging aspect you encounter when approaching your subjects and, also, while defining a theme?

Our process typically begins with an initial idea that gradually evolves into a coherent theme. We delve into the story that inspires us and contemplate how best to visually convey it. Symbolism naturally finds its place in our work as our images often carry deeper connotations. It goes beyond merely interpreting deities or folklore; it also involves linking art historical references and weaving our own personal narrative into the visuals. A significant challenge we initially encountered was ensuring that our subjects grasped our artistic intentions. They don't necessarily need to be familiar with Lucumí or our specific story, but they should comprehend the visual aesthetic we're striving to achieve. When we first started working on this, it was difficult to explain because we had not done it before. However, now that the work exists, we have previous references we can share with our subjects, so they better understand. More so, we remind our subjects that the images go beyond what they look like, because recognizing individuals in these images is usually unlikely. Within portraiture or figurative photography, the subjects tend to focus on what it is they look like but the central emphasis lies on the broader theme and the final image— a sentiment usually grasped upon seeing the finished outcome.

What’s coming up for you?

We are part of a museum show early next year around Caribbean surrealism, which we’re looking forward to! This will take place at The Modern in Dallas, Texas and will encompass Caribbean artists spanning the 1940s to today. We also debut our first public art project which will go up this fall, a monumental site-specific two panel billboard installation of a reclining Venus. The project, which was produced by Fringe Projects, will be on the historic Moore Building at LVMH & DACRA’s Miami Design District.